User login

Which patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease should undergo liver biopsy?

Patients should undergo biopsy to guide management and prognosis if suspected of having steatohepatitis or fibrosis.

WHAT IS NAFLD?

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of chronic liver disease in the United States and is the second most common reason for liver transplant.1 It is thought to be the hepatic consequence of systemic insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NAFLD AND NASH?

NAFLD is defined by the accumulation of hepatic fat as evidenced by imaging or histologic study and without a coexisting cause of chronic liver disease or a secondary cause of hepatic steatosis, including significant alcohol use, medications, or an inherited or acquired metabolic state.

NAFLD has two subtypes: nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFL is characterized by steatosis, including inflammation, in at least 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined by a constellation of features that include steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and liver cell injury in the form of hepatocyte ballooning.2

Clinically, it is especially important to distinguish patients with the NASH subtype, as most NAFLD patients have steatosis without necroinflammation or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF NAFLD: NASH IS WORSE THAN NAFL

NAFL carries an excellent prognosis in terms of histologic progression of liver disease, whereas NASH can histologically progress to fibrosis and, in up to 15% of patients, to cirrhosis.3

Progression of fibrosis poses secondary risks, including complications associated with portal hypertension (ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy), end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In Western countries, 4% to 22% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are attributed to NAFLD.4

In a 2015 meta-analysis, patients with NAFL and stage 0 fibrosis at baseline progressed 1 stage of fibrosis over 14.3 years, whereas patients with NASH and stage 0 fibrosis experienced an accelerated rate of progression, advancing 1 stage of fibrosis over 7.1 years.5 A systematic review of patients with NASH identified age and inflammation on initial liver biopsy as independent predictors of progression to advanced fibrosis.6

Patients with NAFLD have a higher all-cause mortality rate than patients of the same age and sex without NAFLD.7

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS WITH NAFLD BE EVALUATED?

Initial evaluation of a patient with suspected NAFLD should include a thorough serologic evaluation to exclude coexisting causes of chronic liver disease. Tests include:

- A viral hepatitis panel

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

- Antismooth muscle antibody (ASMA)

- Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA)

- Iron studies

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin level

- Ceruloplasmin level.

Aminotransferase levels and imaging studies (ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) do not reliably convey the degree of NASH and fibrosis.

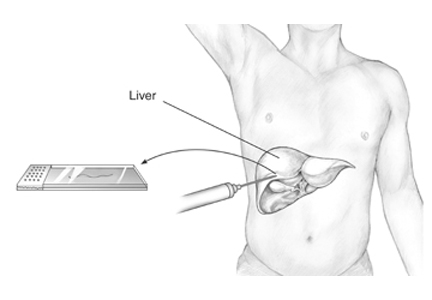

Biopsy. Whereas sensitive serologic tests have been introduced to detect and diagnose many causes of liver disease, liver biopsy (transjugular or percutaneous) with histologic examination remains the only way to accurately assess the degree of steatosis and, thus, to distinguish NAFL from NASH.2

The Pathology Committee of the NASH Clinical Research Network designed and validated a NAFLD scoring system,8,9 with points allocated for degrees of:

- Steatosis (0–3)

- Lobular inflammation (0–2)

- Hepatocellular ballooning (0–2)

- Fibrosis (0–4).

A NAFLD Activity Score of less than 3 is consistent with “not NASH,” a score of 3 or 4 with borderline NASH, and a score of 5 or more with NASH.8 However, the diagnosis of NASH is not based on the NAFLD scoring system, but rather on the pathologist’s overall evaluation of the liver biopsy.9

The metabolic syndrome is an established risk factor for steatohepatitis in patients with NAFLD, and its presence in patients with persistently elevated liver biochemical tests may help identify those who would benefit from further diagnostic and prognostic evaluation, including liver biopsy.2,10 In addition, a 2008 study that used a decision-tree modeling system demonstrated that early liver biopsy could provide a survival benefit.11

NONINVASIVE TESTING

Since liver biopsy is associated with procedure-related morbidity, mortality, and cost, researchers have been developing noninvasive markers of steatohepatitis and fibrosis.12

The NAFLD fibrosis score—based on patient age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, platelet count, albumin, and ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase—has been shown to have an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.85 for predicting advanced fibrosis, with a negative predictive value of 88% to 93% and a positive predictive value of 82% to 90%.13 The NAFLD fibrosis score can be used to identify patients who may have fibrosis or cirrhosis and can help direct the use of liver biopsy in patients who would benefit from prognostication and potential treatment.

Of note, the NAFLD fibrosis score is only slightly less accurate than the imaging techniques of magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography, particularly when the relative costs are considered.14

INDICATIONS FOR LIVER BIOPSY

There are two clear indications for liver biopsy in NAFLD.

Before starting any pharmacologic therapy for NAFLD. Most NAFLD patients have steatosis without NASH or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy. Importantly, the available treatments have significant adverse effects—prostate cancer with vitamin E, bladder cancer and weight gain with pioglitazone, and nausea with pentoxifylline.

Diagnosis. Up to 30% of patients have elevated serum ferritin and autoantibodies, including ANA, ASMA, and AMA. Liver biopsy is often needed to exclude hemochromatosis or autoimmune hepatitis.15 Occasionally, a possible confounding drug-induced liver injury may necessitate a liver biopsy.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION

The first step in managing patients who have NAFLD is to treat components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

In a randomized controlled trial in 31 obese patients with biopsy-proven NASH,16 intensive lifestyle modification (consisting of diet, behavior modification, and 200 minutes of exercise weekly for 48 weeks) was shown to improve histologic NAFLD Activity Scores, including degrees of steatosis, necrosis, and inflammation. As a result, weight loss of 7% to 9% is generally recommended for patients with NAFLD.

DRUG THERAPIES

Much research has been directed toward identifying risk factors for progression of fibrosis and toward developing new therapies for patients with NAFLD. A 2015 meta-analysis concluded that pentoxifylline and obeticholic acid improve fibrosis, while vitamin E, thiazolidinediones, and obeticholic acid improve necroinflammation associated with NASH.17

Long-term studies are needed to determine the impact of these drugs on NASH-related morbidity, mortality, and need for liver transplant.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and is increasing as a reason for liver transplant.

- NASH is associated with the metabolic syndrome and can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease. Noninvasive markers such as the NAFLD Activity Score can be useful in identifying patients who may have advanced fibrosis and can select patients who should be directed to liver biopsy for definitive diagnosis.8,9

- Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing steatohepatitis and fibrosis and is the only diagnostic tool used in clinical trials to direct pharmacotherapy for NASH.

- Liver biopsy should be reserved for patients suspected of having NASH or fibrosis and who might benefit from therapy.

- Liver biopsy is also indicated for those NAFLD patients who have confounding laboratory findings such as an elevated ferritin level and autoantibodies including ANA, ASMA, and AMA.

- Wong RJ, Aquilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015; 148:547–555.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1592–1609.

- Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology 2006; 44:865–873.

- Michelotti GA, Machado MV, Diehl AM. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:656–665.

- Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:643–654.

- Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AM, Caldwell SH. Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2009; 51:371–379.

- Adams LA, Lymp JF, St. Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129:113–121.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41:1313–1321.

- Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander-Tetri BA; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011; 53:810–820.

- Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 2003; 37:917–923.

- Gaidos JK, Hillner BE, Sanyal AJ. A decision analysis study of the value of a liver biopsy in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int 2008; 28:650–658.

- Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med 2011; 43:617–649.

- Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007; 45:846–854.

- Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging more accurately classifies steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease than transient elastography. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:626–637.e7.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, et al; NASH Clinical Research Network. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010; 52:913–924.

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51:121–129.

- Singh S, Khera R, Allen AM, Murad H, Loomba R. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology 2015; 62:1417–1432.

Patients should undergo biopsy to guide management and prognosis if suspected of having steatohepatitis or fibrosis.

WHAT IS NAFLD?

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of chronic liver disease in the United States and is the second most common reason for liver transplant.1 It is thought to be the hepatic consequence of systemic insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NAFLD AND NASH?

NAFLD is defined by the accumulation of hepatic fat as evidenced by imaging or histologic study and without a coexisting cause of chronic liver disease or a secondary cause of hepatic steatosis, including significant alcohol use, medications, or an inherited or acquired metabolic state.

NAFLD has two subtypes: nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFL is characterized by steatosis, including inflammation, in at least 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined by a constellation of features that include steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and liver cell injury in the form of hepatocyte ballooning.2

Clinically, it is especially important to distinguish patients with the NASH subtype, as most NAFLD patients have steatosis without necroinflammation or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF NAFLD: NASH IS WORSE THAN NAFL

NAFL carries an excellent prognosis in terms of histologic progression of liver disease, whereas NASH can histologically progress to fibrosis and, in up to 15% of patients, to cirrhosis.3

Progression of fibrosis poses secondary risks, including complications associated with portal hypertension (ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy), end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In Western countries, 4% to 22% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are attributed to NAFLD.4

In a 2015 meta-analysis, patients with NAFL and stage 0 fibrosis at baseline progressed 1 stage of fibrosis over 14.3 years, whereas patients with NASH and stage 0 fibrosis experienced an accelerated rate of progression, advancing 1 stage of fibrosis over 7.1 years.5 A systematic review of patients with NASH identified age and inflammation on initial liver biopsy as independent predictors of progression to advanced fibrosis.6

Patients with NAFLD have a higher all-cause mortality rate than patients of the same age and sex without NAFLD.7

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS WITH NAFLD BE EVALUATED?

Initial evaluation of a patient with suspected NAFLD should include a thorough serologic evaluation to exclude coexisting causes of chronic liver disease. Tests include:

- A viral hepatitis panel

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

- Antismooth muscle antibody (ASMA)

- Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA)

- Iron studies

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin level

- Ceruloplasmin level.

Aminotransferase levels and imaging studies (ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) do not reliably convey the degree of NASH and fibrosis.

Biopsy. Whereas sensitive serologic tests have been introduced to detect and diagnose many causes of liver disease, liver biopsy (transjugular or percutaneous) with histologic examination remains the only way to accurately assess the degree of steatosis and, thus, to distinguish NAFL from NASH.2

The Pathology Committee of the NASH Clinical Research Network designed and validated a NAFLD scoring system,8,9 with points allocated for degrees of:

- Steatosis (0–3)

- Lobular inflammation (0–2)

- Hepatocellular ballooning (0–2)

- Fibrosis (0–4).

A NAFLD Activity Score of less than 3 is consistent with “not NASH,” a score of 3 or 4 with borderline NASH, and a score of 5 or more with NASH.8 However, the diagnosis of NASH is not based on the NAFLD scoring system, but rather on the pathologist’s overall evaluation of the liver biopsy.9

The metabolic syndrome is an established risk factor for steatohepatitis in patients with NAFLD, and its presence in patients with persistently elevated liver biochemical tests may help identify those who would benefit from further diagnostic and prognostic evaluation, including liver biopsy.2,10 In addition, a 2008 study that used a decision-tree modeling system demonstrated that early liver biopsy could provide a survival benefit.11

NONINVASIVE TESTING

Since liver biopsy is associated with procedure-related morbidity, mortality, and cost, researchers have been developing noninvasive markers of steatohepatitis and fibrosis.12

The NAFLD fibrosis score—based on patient age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, platelet count, albumin, and ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase—has been shown to have an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.85 for predicting advanced fibrosis, with a negative predictive value of 88% to 93% and a positive predictive value of 82% to 90%.13 The NAFLD fibrosis score can be used to identify patients who may have fibrosis or cirrhosis and can help direct the use of liver biopsy in patients who would benefit from prognostication and potential treatment.

Of note, the NAFLD fibrosis score is only slightly less accurate than the imaging techniques of magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography, particularly when the relative costs are considered.14

INDICATIONS FOR LIVER BIOPSY

There are two clear indications for liver biopsy in NAFLD.

Before starting any pharmacologic therapy for NAFLD. Most NAFLD patients have steatosis without NASH or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy. Importantly, the available treatments have significant adverse effects—prostate cancer with vitamin E, bladder cancer and weight gain with pioglitazone, and nausea with pentoxifylline.

Diagnosis. Up to 30% of patients have elevated serum ferritin and autoantibodies, including ANA, ASMA, and AMA. Liver biopsy is often needed to exclude hemochromatosis or autoimmune hepatitis.15 Occasionally, a possible confounding drug-induced liver injury may necessitate a liver biopsy.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION

The first step in managing patients who have NAFLD is to treat components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

In a randomized controlled trial in 31 obese patients with biopsy-proven NASH,16 intensive lifestyle modification (consisting of diet, behavior modification, and 200 minutes of exercise weekly for 48 weeks) was shown to improve histologic NAFLD Activity Scores, including degrees of steatosis, necrosis, and inflammation. As a result, weight loss of 7% to 9% is generally recommended for patients with NAFLD.

DRUG THERAPIES

Much research has been directed toward identifying risk factors for progression of fibrosis and toward developing new therapies for patients with NAFLD. A 2015 meta-analysis concluded that pentoxifylline and obeticholic acid improve fibrosis, while vitamin E, thiazolidinediones, and obeticholic acid improve necroinflammation associated with NASH.17

Long-term studies are needed to determine the impact of these drugs on NASH-related morbidity, mortality, and need for liver transplant.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and is increasing as a reason for liver transplant.

- NASH is associated with the metabolic syndrome and can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease. Noninvasive markers such as the NAFLD Activity Score can be useful in identifying patients who may have advanced fibrosis and can select patients who should be directed to liver biopsy for definitive diagnosis.8,9

- Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing steatohepatitis and fibrosis and is the only diagnostic tool used in clinical trials to direct pharmacotherapy for NASH.

- Liver biopsy should be reserved for patients suspected of having NASH or fibrosis and who might benefit from therapy.

- Liver biopsy is also indicated for those NAFLD patients who have confounding laboratory findings such as an elevated ferritin level and autoantibodies including ANA, ASMA, and AMA.

Patients should undergo biopsy to guide management and prognosis if suspected of having steatohepatitis or fibrosis.

WHAT IS NAFLD?

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of chronic liver disease in the United States and is the second most common reason for liver transplant.1 It is thought to be the hepatic consequence of systemic insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NAFLD AND NASH?

NAFLD is defined by the accumulation of hepatic fat as evidenced by imaging or histologic study and without a coexisting cause of chronic liver disease or a secondary cause of hepatic steatosis, including significant alcohol use, medications, or an inherited or acquired metabolic state.

NAFLD has two subtypes: nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFL is characterized by steatosis, including inflammation, in at least 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined by a constellation of features that include steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and liver cell injury in the form of hepatocyte ballooning.2

Clinically, it is especially important to distinguish patients with the NASH subtype, as most NAFLD patients have steatosis without necroinflammation or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF NAFLD: NASH IS WORSE THAN NAFL

NAFL carries an excellent prognosis in terms of histologic progression of liver disease, whereas NASH can histologically progress to fibrosis and, in up to 15% of patients, to cirrhosis.3

Progression of fibrosis poses secondary risks, including complications associated with portal hypertension (ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy), end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In Western countries, 4% to 22% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are attributed to NAFLD.4

In a 2015 meta-analysis, patients with NAFL and stage 0 fibrosis at baseline progressed 1 stage of fibrosis over 14.3 years, whereas patients with NASH and stage 0 fibrosis experienced an accelerated rate of progression, advancing 1 stage of fibrosis over 7.1 years.5 A systematic review of patients with NASH identified age and inflammation on initial liver biopsy as independent predictors of progression to advanced fibrosis.6

Patients with NAFLD have a higher all-cause mortality rate than patients of the same age and sex without NAFLD.7

HOW SHOULD PATIENTS WITH NAFLD BE EVALUATED?

Initial evaluation of a patient with suspected NAFLD should include a thorough serologic evaluation to exclude coexisting causes of chronic liver disease. Tests include:

- A viral hepatitis panel

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

- Antismooth muscle antibody (ASMA)

- Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA)

- Iron studies

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin level

- Ceruloplasmin level.

Aminotransferase levels and imaging studies (ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) do not reliably convey the degree of NASH and fibrosis.

Biopsy. Whereas sensitive serologic tests have been introduced to detect and diagnose many causes of liver disease, liver biopsy (transjugular or percutaneous) with histologic examination remains the only way to accurately assess the degree of steatosis and, thus, to distinguish NAFL from NASH.2

The Pathology Committee of the NASH Clinical Research Network designed and validated a NAFLD scoring system,8,9 with points allocated for degrees of:

- Steatosis (0–3)

- Lobular inflammation (0–2)

- Hepatocellular ballooning (0–2)

- Fibrosis (0–4).

A NAFLD Activity Score of less than 3 is consistent with “not NASH,” a score of 3 or 4 with borderline NASH, and a score of 5 or more with NASH.8 However, the diagnosis of NASH is not based on the NAFLD scoring system, but rather on the pathologist’s overall evaluation of the liver biopsy.9

The metabolic syndrome is an established risk factor for steatohepatitis in patients with NAFLD, and its presence in patients with persistently elevated liver biochemical tests may help identify those who would benefit from further diagnostic and prognostic evaluation, including liver biopsy.2,10 In addition, a 2008 study that used a decision-tree modeling system demonstrated that early liver biopsy could provide a survival benefit.11

NONINVASIVE TESTING

Since liver biopsy is associated with procedure-related morbidity, mortality, and cost, researchers have been developing noninvasive markers of steatohepatitis and fibrosis.12

The NAFLD fibrosis score—based on patient age, body mass index, hyperglycemia, platelet count, albumin, and ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase—has been shown to have an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.85 for predicting advanced fibrosis, with a negative predictive value of 88% to 93% and a positive predictive value of 82% to 90%.13 The NAFLD fibrosis score can be used to identify patients who may have fibrosis or cirrhosis and can help direct the use of liver biopsy in patients who would benefit from prognostication and potential treatment.

Of note, the NAFLD fibrosis score is only slightly less accurate than the imaging techniques of magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography, particularly when the relative costs are considered.14

INDICATIONS FOR LIVER BIOPSY

There are two clear indications for liver biopsy in NAFLD.

Before starting any pharmacologic therapy for NAFLD. Most NAFLD patients have steatosis without NASH or fibrosis and do not require medical therapy. Importantly, the available treatments have significant adverse effects—prostate cancer with vitamin E, bladder cancer and weight gain with pioglitazone, and nausea with pentoxifylline.

Diagnosis. Up to 30% of patients have elevated serum ferritin and autoantibodies, including ANA, ASMA, and AMA. Liver biopsy is often needed to exclude hemochromatosis or autoimmune hepatitis.15 Occasionally, a possible confounding drug-induced liver injury may necessitate a liver biopsy.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION

The first step in managing patients who have NAFLD is to treat components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

In a randomized controlled trial in 31 obese patients with biopsy-proven NASH,16 intensive lifestyle modification (consisting of diet, behavior modification, and 200 minutes of exercise weekly for 48 weeks) was shown to improve histologic NAFLD Activity Scores, including degrees of steatosis, necrosis, and inflammation. As a result, weight loss of 7% to 9% is generally recommended for patients with NAFLD.

DRUG THERAPIES

Much research has been directed toward identifying risk factors for progression of fibrosis and toward developing new therapies for patients with NAFLD. A 2015 meta-analysis concluded that pentoxifylline and obeticholic acid improve fibrosis, while vitamin E, thiazolidinediones, and obeticholic acid improve necroinflammation associated with NASH.17

Long-term studies are needed to determine the impact of these drugs on NASH-related morbidity, mortality, and need for liver transplant.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- NAFLD is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and is increasing as a reason for liver transplant.

- NASH is associated with the metabolic syndrome and can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease. Noninvasive markers such as the NAFLD Activity Score can be useful in identifying patients who may have advanced fibrosis and can select patients who should be directed to liver biopsy for definitive diagnosis.8,9

- Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing steatohepatitis and fibrosis and is the only diagnostic tool used in clinical trials to direct pharmacotherapy for NASH.

- Liver biopsy should be reserved for patients suspected of having NASH or fibrosis and who might benefit from therapy.

- Liver biopsy is also indicated for those NAFLD patients who have confounding laboratory findings such as an elevated ferritin level and autoantibodies including ANA, ASMA, and AMA.

- Wong RJ, Aquilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015; 148:547–555.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1592–1609.

- Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology 2006; 44:865–873.

- Michelotti GA, Machado MV, Diehl AM. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:656–665.

- Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:643–654.

- Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AM, Caldwell SH. Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2009; 51:371–379.

- Adams LA, Lymp JF, St. Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129:113–121.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41:1313–1321.

- Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander-Tetri BA; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011; 53:810–820.

- Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 2003; 37:917–923.

- Gaidos JK, Hillner BE, Sanyal AJ. A decision analysis study of the value of a liver biopsy in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int 2008; 28:650–658.

- Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med 2011; 43:617–649.

- Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007; 45:846–854.

- Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging more accurately classifies steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease than transient elastography. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:626–637.e7.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, et al; NASH Clinical Research Network. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010; 52:913–924.

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51:121–129.

- Singh S, Khera R, Allen AM, Murad H, Loomba R. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology 2015; 62:1417–1432.

- Wong RJ, Aquilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015; 148:547–555.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1592–1609.

- Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology 2006; 44:865–873.

- Michelotti GA, Machado MV, Diehl AM. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:656–665.

- Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Loomba R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:643–654.

- Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AM, Caldwell SH. Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2009; 51:371–379.

- Adams LA, Lymp JF, St. Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129:113–121.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41:1313–1321.

- Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander-Tetri BA; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011; 53:810–820.

- Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 2003; 37:917–923.

- Gaidos JK, Hillner BE, Sanyal AJ. A decision analysis study of the value of a liver biopsy in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int 2008; 28:650–658.

- Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med 2011; 43:617–649.

- Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007; 45:846–854.

- Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging more accurately classifies steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease than transient elastography. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:626–637.e7.

- Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, et al; NASH Clinical Research Network. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010; 52:913–924.

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51:121–129.

- Singh S, Khera R, Allen AM, Murad H, Loomba R. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology 2015; 62:1417–1432.