User login

Heparin Drug Shortage Conservation Strategies

Heparin is the anticoagulant of choice when a rapid anticoagulant is indicated: Onset of action is immediate when administered IV as a bolus.1 The major anticoagulant effect of heparin is mediated by heparin/antithrombin (AT) interaction. Heparin/AT inactivates factor IIa (thrombin) and factors Xa, IXa, XIa, and XIIa. Heparin is approved for multiple indications, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) treatment and prophylaxis of medical and surgical patients; stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF); acute coronary syndrome (ACS); vascular and cardiac surgeries; and various interventional procedures (eg, diagnostic angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). It also is used as an anticoagulant in blood transfusions, extracorporeal circulation, and for maintaining patency of central vascular access devices (CVADs).

About 60% of the crude heparin used to manufacture heparin in the US originates in China, derived from porcine mucosa. African swine fever, a contagious virus with no cure, has eliminated about 25% to 35% of China’s pig population, or about 150 million pigs. In July 2019, members of the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter to the US Food and Drug Administration asking for details on the potential impact of African swine fever on the supply of heparin.2

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) heath care system is currently experiencing a shortage of heparin vials and syringes. It is unclear when resolution of this shortage will occur as it could resolve within several weeks or as late as January 2020.3 Although vials and syringes are the current products that are affected, it is possible the shortage may eventually include IV heparin bags as well.

Since the foremost objective of VA health care providers is to provide timely access to medications for veterans, strategies to conserve unfractionated heparin (UfH) must be used since it is a first-line therapy where few evidence-based alternatives exist. Conservation strategies may include drug rationing, therapeutic substitution, and compounding of needed products using the limited stock available in the pharmacy.4 It is important that all staff are educated on facility strategies in order to be familiar with alternatives and limit the potential for near misses, adverse events, and provider frustration.

In shortage situations, the VA-Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) defers decisions regarding drug preservation, processes to shift to viable alternatives, and the best practice for safe transitions to local facilities and their subject matter experts.5 At the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, a 1A, tertiary, dual campus health care system, a pharmacy task force has formed to track drug shortages impacting the facility’s efficiencies and budgets. This group communicates with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee about potential risks to patient care and develops shortage briefs (following an SBAR [situation, background, assessment, recommendation] design) generally authored and championed by at least 1 clinical pharmacy specialist and supervising physicians who are field experts. Prior to dissemination, the SBAR undergoes a rapid peer-review process.

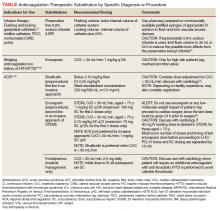

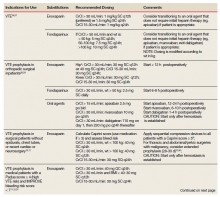

To date, VA PBM has not issued specific guidance on how pharmacists should proceed in case of a shortage. However, we recommend strategies that may be considered for implementation during a potential UfH shortage. For example, pharmacists can use therapeutic alternatives for which best available evidence suggests no disadvantage.4 The Table lists alternative agents according to indication and patient-specific considerations that may preclude use. Existing UfH products may also be used for drug compounding (eg, use current stock to provide an indicated aliquot) to meet the need of prioritized patients.4 In addition, we suggest prioritizing current UfH/heparinized saline for use for the following groups of patients4:

- Emergent/urgent cardiac surgery1,6;

- Hemodialysis patients1,7-9 for which the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) dalteparin is deemed inappropriate or the patient is not monitored in the intensive care unit for regional citrate administration;

- VTE prophylaxis for patients with epidurals or chest tubes for which urgent invasive management may occur, recent cardiac or neurosurgery, or for patients with a creatine clearance < 15 mL/min or receiving hemodialysis10-12;

- Vascular surgery (eg, limb ischemia) and interventions (eg, carotid stenting, endarterectomy)13,14;

- Mesenteric ischemia (venous thrombosis) with a potential to proceed to laparotomy15;

- Critically ill patients with arterial lines for which normal saline is deemed inappropriate for line flushing16;

- Electrophysiology procedures (eg, AF ablation)17; and

- Contraindication to use of a long-acting alternative listed in the table or a medical necessity exists for using a rapidly reversible agent. Examples for this category include but are not limited to recent gastrointestinal bleeding, central nervous system lesion, and select neurologic diagnoses (eg, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with hemorrhage, thrombus in vertebral basilar system or anterior circulation, intraparenchymal hemorrhage plus mechanical valve, medium to large cardioembolic stroke with intracardiac thrombus).

Conclusion

The UfH drug shortage represents a significant threat to public health and is a major challenge for US health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration. Overreliance on a predominant source of crude heparin has affected multiple UfH manufacturers and products. Current alternatives to UfH include low-molecular-weight heparins, IV direct thrombin inhibitors, and SC fondaparinux, with selection supported by guidelines or evolving literature. However, the shortage has the potential to expand to other injectables, such as dalteparin and enoxaparin, and severely limit care for veterans. It is vital that clinicians rapidly address the current shortage by creating a plan to develop efficient and equitable access to UfH, continue to assess supply and update stakeholders, and select evidence-based alternatives while maintaining focus on efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Yost, PharmD, for her coordination of the multidisciplinary task force assigned to efficiently manage the heparin drug shortage. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee.

1. Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119(1):64S-94S.

2. Bipartisan E&C leaders request FDA briefing on threat to U.S. heparin supply [press release]. Washington, DC: House Committee on Energy and Commerce; July 30, 2019. https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/bipartisan-ec-leaders-request-fda-briefing-on-threat-to-us-heparin-supply. Accessed September 19, 2019.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages. Heparin injection. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortages-List?page=CurrentShortages. Accessed September 19, 2019.

4. Reed BN, Fox ER, Konig M, et al. The impact of drug shortages on patients with cardiovascular disease: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am Heart J. 2016;175:130-141.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, VISN Pharmacist Executives, The Center For Medication Safety. Heparin supply status: frequently asked questions. PBM-2018-02. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/vacenterformedicationsafety/HeparinandSalineSyringeRecallDuetoContamination_NationalPBMPati.pdf. Published May 3, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

6. Shore-Lesserson I, Baker RA, Ferraris VA, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines-anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):650-662.

7. Soroka S, Agharazii M, Donnelly S, et al. An adjustable dalteparin sodium dose regimen for the prevention of clotting in the extracorporeal circuit in hemodialysis: a clinical trial of safety and efficacy (the PARROT Study). Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1-12.

8. Shantha GPS, Kumar AA, Sethi M, Khanna RC, Pancholy SB. Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin compared to unfractionated heparin for chronic outpatient hemodialysis in end stage renal disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Peer J. 2015;3:e835.

9. Kessler M, Moureau F, and Nguyen P. Anticoagulation in chronic hemodialysis: progress toward an optimal approach. Semin Dial. 2015;28(5):474-489.

10. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e227s-e277S.

11. Kaye AD, Brunk AJ, Kaye AJ, et al. Regional anesthesia in patients on anticoagulation therapies—evidence-based recommendations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(9):67.

12. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e195S-e226S.

13. Naylor AR, Ricco JB, de Borst GJ, et al. Management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease: 2017 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:3-81.

14. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2017;69(11): e71-e126.

15. Bjorck M, Koelemaya M, Acosta S, et al. Management of diseases of mesenteric arteries and veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53(4):460-510.

16. Gorski L, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, McGoldrick M, Orr M, Doellman D. Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infusion Nurs. 2016;39:S1-S156.

17. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(10):e275-e444.

18. Spyropoulos AC, Al-Badri A, Sherwood MW, Douketis JD. Periprocedural management of patients receiving a vitamin K antagonist or a direct oral anticoagulant requiring an elective procedure or surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(5):875-885.

, . Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation. 2012;126(4):486-490.

20. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e326S-e350S.

21. Sousa-Uva M, Neumann F-J, Ahlsson A, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with a special contribution of the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55(1):4-90.

22. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

23. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

24. Angiomax [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: The Medicines Company; March 2016.

25. Sousa-Uva, Head SJ, Milojevic M, et al. 2017 EACTS guidelines on perioperative medication in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53(1):5-33.

26. Witt DM, Nieuwlaat R, Clark NP, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for the management of venous thromboembolism: optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018: 2(22):3257-3291

27. Kearon C, Akl EA, Blaivas A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

28. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Manager Service. Direct oral anticoagulants criteria for use and algorithm for venous thromboembolism treatment. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/criteriaforuse.asp. Updated December 2016. [Source not verified]

29. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e278S-e325S.

30. Raja S, Idrees JJ, Blackstone EH, et al. Routine venous thromboembolism screening after pneumonectomy: the more you look, the more you see. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):524-532.e2.

31. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225.

32. Naidu SS, Aronow HD, Box LC, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement: 2016 best practices in the cardiac catheterization laboratory:(endorsed by the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencionista; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(3):407-423.

33. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. JACC. 2011;58(24):e44-e122.

34. Mason PJ, Shah B, Tamis-Holland JE, et al; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine. AHA scientific statement: an update on radial artery access and best practices for transradial coronary angiography and intervention in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(9):e000035.

35. Rao SV, Tremmel JA, Gilchrist IC, et al; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention’s Transradial Working Group. Best practices for transradial angiography and intervention: a consensus statement from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions’ transradial working group. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(2):228-236. 36. Moran JE, Ash SR. Locking solutions for hemodialysis catheters; heparin and citrate: a position paper by ASDIN. Semin Dial. 2008;21(5):490-492.

Heparin is the anticoagulant of choice when a rapid anticoagulant is indicated: Onset of action is immediate when administered IV as a bolus.1 The major anticoagulant effect of heparin is mediated by heparin/antithrombin (AT) interaction. Heparin/AT inactivates factor IIa (thrombin) and factors Xa, IXa, XIa, and XIIa. Heparin is approved for multiple indications, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) treatment and prophylaxis of medical and surgical patients; stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF); acute coronary syndrome (ACS); vascular and cardiac surgeries; and various interventional procedures (eg, diagnostic angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). It also is used as an anticoagulant in blood transfusions, extracorporeal circulation, and for maintaining patency of central vascular access devices (CVADs).

About 60% of the crude heparin used to manufacture heparin in the US originates in China, derived from porcine mucosa. African swine fever, a contagious virus with no cure, has eliminated about 25% to 35% of China’s pig population, or about 150 million pigs. In July 2019, members of the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter to the US Food and Drug Administration asking for details on the potential impact of African swine fever on the supply of heparin.2

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) heath care system is currently experiencing a shortage of heparin vials and syringes. It is unclear when resolution of this shortage will occur as it could resolve within several weeks or as late as January 2020.3 Although vials and syringes are the current products that are affected, it is possible the shortage may eventually include IV heparin bags as well.

Since the foremost objective of VA health care providers is to provide timely access to medications for veterans, strategies to conserve unfractionated heparin (UfH) must be used since it is a first-line therapy where few evidence-based alternatives exist. Conservation strategies may include drug rationing, therapeutic substitution, and compounding of needed products using the limited stock available in the pharmacy.4 It is important that all staff are educated on facility strategies in order to be familiar with alternatives and limit the potential for near misses, adverse events, and provider frustration.

In shortage situations, the VA-Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) defers decisions regarding drug preservation, processes to shift to viable alternatives, and the best practice for safe transitions to local facilities and their subject matter experts.5 At the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, a 1A, tertiary, dual campus health care system, a pharmacy task force has formed to track drug shortages impacting the facility’s efficiencies and budgets. This group communicates with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee about potential risks to patient care and develops shortage briefs (following an SBAR [situation, background, assessment, recommendation] design) generally authored and championed by at least 1 clinical pharmacy specialist and supervising physicians who are field experts. Prior to dissemination, the SBAR undergoes a rapid peer-review process.

To date, VA PBM has not issued specific guidance on how pharmacists should proceed in case of a shortage. However, we recommend strategies that may be considered for implementation during a potential UfH shortage. For example, pharmacists can use therapeutic alternatives for which best available evidence suggests no disadvantage.4 The Table lists alternative agents according to indication and patient-specific considerations that may preclude use. Existing UfH products may also be used for drug compounding (eg, use current stock to provide an indicated aliquot) to meet the need of prioritized patients.4 In addition, we suggest prioritizing current UfH/heparinized saline for use for the following groups of patients4:

- Emergent/urgent cardiac surgery1,6;

- Hemodialysis patients1,7-9 for which the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) dalteparin is deemed inappropriate or the patient is not monitored in the intensive care unit for regional citrate administration;

- VTE prophylaxis for patients with epidurals or chest tubes for which urgent invasive management may occur, recent cardiac or neurosurgery, or for patients with a creatine clearance < 15 mL/min or receiving hemodialysis10-12;

- Vascular surgery (eg, limb ischemia) and interventions (eg, carotid stenting, endarterectomy)13,14;

- Mesenteric ischemia (venous thrombosis) with a potential to proceed to laparotomy15;

- Critically ill patients with arterial lines for which normal saline is deemed inappropriate for line flushing16;

- Electrophysiology procedures (eg, AF ablation)17; and

- Contraindication to use of a long-acting alternative listed in the table or a medical necessity exists for using a rapidly reversible agent. Examples for this category include but are not limited to recent gastrointestinal bleeding, central nervous system lesion, and select neurologic diagnoses (eg, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with hemorrhage, thrombus in vertebral basilar system or anterior circulation, intraparenchymal hemorrhage plus mechanical valve, medium to large cardioembolic stroke with intracardiac thrombus).

Conclusion

The UfH drug shortage represents a significant threat to public health and is a major challenge for US health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration. Overreliance on a predominant source of crude heparin has affected multiple UfH manufacturers and products. Current alternatives to UfH include low-molecular-weight heparins, IV direct thrombin inhibitors, and SC fondaparinux, with selection supported by guidelines or evolving literature. However, the shortage has the potential to expand to other injectables, such as dalteparin and enoxaparin, and severely limit care for veterans. It is vital that clinicians rapidly address the current shortage by creating a plan to develop efficient and equitable access to UfH, continue to assess supply and update stakeholders, and select evidence-based alternatives while maintaining focus on efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Yost, PharmD, for her coordination of the multidisciplinary task force assigned to efficiently manage the heparin drug shortage. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee.

Heparin is the anticoagulant of choice when a rapid anticoagulant is indicated: Onset of action is immediate when administered IV as a bolus.1 The major anticoagulant effect of heparin is mediated by heparin/antithrombin (AT) interaction. Heparin/AT inactivates factor IIa (thrombin) and factors Xa, IXa, XIa, and XIIa. Heparin is approved for multiple indications, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) treatment and prophylaxis of medical and surgical patients; stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF); acute coronary syndrome (ACS); vascular and cardiac surgeries; and various interventional procedures (eg, diagnostic angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). It also is used as an anticoagulant in blood transfusions, extracorporeal circulation, and for maintaining patency of central vascular access devices (CVADs).

About 60% of the crude heparin used to manufacture heparin in the US originates in China, derived from porcine mucosa. African swine fever, a contagious virus with no cure, has eliminated about 25% to 35% of China’s pig population, or about 150 million pigs. In July 2019, members of the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter to the US Food and Drug Administration asking for details on the potential impact of African swine fever on the supply of heparin.2

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) heath care system is currently experiencing a shortage of heparin vials and syringes. It is unclear when resolution of this shortage will occur as it could resolve within several weeks or as late as January 2020.3 Although vials and syringes are the current products that are affected, it is possible the shortage may eventually include IV heparin bags as well.

Since the foremost objective of VA health care providers is to provide timely access to medications for veterans, strategies to conserve unfractionated heparin (UfH) must be used since it is a first-line therapy where few evidence-based alternatives exist. Conservation strategies may include drug rationing, therapeutic substitution, and compounding of needed products using the limited stock available in the pharmacy.4 It is important that all staff are educated on facility strategies in order to be familiar with alternatives and limit the potential for near misses, adverse events, and provider frustration.

In shortage situations, the VA-Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) defers decisions regarding drug preservation, processes to shift to viable alternatives, and the best practice for safe transitions to local facilities and their subject matter experts.5 At the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, a 1A, tertiary, dual campus health care system, a pharmacy task force has formed to track drug shortages impacting the facility’s efficiencies and budgets. This group communicates with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee about potential risks to patient care and develops shortage briefs (following an SBAR [situation, background, assessment, recommendation] design) generally authored and championed by at least 1 clinical pharmacy specialist and supervising physicians who are field experts. Prior to dissemination, the SBAR undergoes a rapid peer-review process.

To date, VA PBM has not issued specific guidance on how pharmacists should proceed in case of a shortage. However, we recommend strategies that may be considered for implementation during a potential UfH shortage. For example, pharmacists can use therapeutic alternatives for which best available evidence suggests no disadvantage.4 The Table lists alternative agents according to indication and patient-specific considerations that may preclude use. Existing UfH products may also be used for drug compounding (eg, use current stock to provide an indicated aliquot) to meet the need of prioritized patients.4 In addition, we suggest prioritizing current UfH/heparinized saline for use for the following groups of patients4:

- Emergent/urgent cardiac surgery1,6;

- Hemodialysis patients1,7-9 for which the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) dalteparin is deemed inappropriate or the patient is not monitored in the intensive care unit for regional citrate administration;

- VTE prophylaxis for patients with epidurals or chest tubes for which urgent invasive management may occur, recent cardiac or neurosurgery, or for patients with a creatine clearance < 15 mL/min or receiving hemodialysis10-12;

- Vascular surgery (eg, limb ischemia) and interventions (eg, carotid stenting, endarterectomy)13,14;

- Mesenteric ischemia (venous thrombosis) with a potential to proceed to laparotomy15;

- Critically ill patients with arterial lines for which normal saline is deemed inappropriate for line flushing16;

- Electrophysiology procedures (eg, AF ablation)17; and

- Contraindication to use of a long-acting alternative listed in the table or a medical necessity exists for using a rapidly reversible agent. Examples for this category include but are not limited to recent gastrointestinal bleeding, central nervous system lesion, and select neurologic diagnoses (eg, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with hemorrhage, thrombus in vertebral basilar system or anterior circulation, intraparenchymal hemorrhage plus mechanical valve, medium to large cardioembolic stroke with intracardiac thrombus).

Conclusion

The UfH drug shortage represents a significant threat to public health and is a major challenge for US health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration. Overreliance on a predominant source of crude heparin has affected multiple UfH manufacturers and products. Current alternatives to UfH include low-molecular-weight heparins, IV direct thrombin inhibitors, and SC fondaparinux, with selection supported by guidelines or evolving literature. However, the shortage has the potential to expand to other injectables, such as dalteparin and enoxaparin, and severely limit care for veterans. It is vital that clinicians rapidly address the current shortage by creating a plan to develop efficient and equitable access to UfH, continue to assess supply and update stakeholders, and select evidence-based alternatives while maintaining focus on efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Yost, PharmD, for her coordination of the multidisciplinary task force assigned to efficiently manage the heparin drug shortage. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee.

1. Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119(1):64S-94S.

2. Bipartisan E&C leaders request FDA briefing on threat to U.S. heparin supply [press release]. Washington, DC: House Committee on Energy and Commerce; July 30, 2019. https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/bipartisan-ec-leaders-request-fda-briefing-on-threat-to-us-heparin-supply. Accessed September 19, 2019.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages. Heparin injection. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortages-List?page=CurrentShortages. Accessed September 19, 2019.

4. Reed BN, Fox ER, Konig M, et al. The impact of drug shortages on patients with cardiovascular disease: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am Heart J. 2016;175:130-141.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, VISN Pharmacist Executives, The Center For Medication Safety. Heparin supply status: frequently asked questions. PBM-2018-02. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/vacenterformedicationsafety/HeparinandSalineSyringeRecallDuetoContamination_NationalPBMPati.pdf. Published May 3, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

6. Shore-Lesserson I, Baker RA, Ferraris VA, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines-anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):650-662.

7. Soroka S, Agharazii M, Donnelly S, et al. An adjustable dalteparin sodium dose regimen for the prevention of clotting in the extracorporeal circuit in hemodialysis: a clinical trial of safety and efficacy (the PARROT Study). Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1-12.

8. Shantha GPS, Kumar AA, Sethi M, Khanna RC, Pancholy SB. Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin compared to unfractionated heparin for chronic outpatient hemodialysis in end stage renal disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Peer J. 2015;3:e835.

9. Kessler M, Moureau F, and Nguyen P. Anticoagulation in chronic hemodialysis: progress toward an optimal approach. Semin Dial. 2015;28(5):474-489.

10. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e227s-e277S.

11. Kaye AD, Brunk AJ, Kaye AJ, et al. Regional anesthesia in patients on anticoagulation therapies—evidence-based recommendations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(9):67.

12. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e195S-e226S.

13. Naylor AR, Ricco JB, de Borst GJ, et al. Management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease: 2017 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:3-81.

14. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2017;69(11): e71-e126.

15. Bjorck M, Koelemaya M, Acosta S, et al. Management of diseases of mesenteric arteries and veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53(4):460-510.

16. Gorski L, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, McGoldrick M, Orr M, Doellman D. Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infusion Nurs. 2016;39:S1-S156.

17. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(10):e275-e444.

18. Spyropoulos AC, Al-Badri A, Sherwood MW, Douketis JD. Periprocedural management of patients receiving a vitamin K antagonist or a direct oral anticoagulant requiring an elective procedure or surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(5):875-885.

, . Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation. 2012;126(4):486-490.

20. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e326S-e350S.

21. Sousa-Uva M, Neumann F-J, Ahlsson A, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with a special contribution of the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55(1):4-90.

22. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

23. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

24. Angiomax [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: The Medicines Company; March 2016.

25. Sousa-Uva, Head SJ, Milojevic M, et al. 2017 EACTS guidelines on perioperative medication in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53(1):5-33.

26. Witt DM, Nieuwlaat R, Clark NP, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for the management of venous thromboembolism: optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018: 2(22):3257-3291

27. Kearon C, Akl EA, Blaivas A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

28. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Manager Service. Direct oral anticoagulants criteria for use and algorithm for venous thromboembolism treatment. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/criteriaforuse.asp. Updated December 2016. [Source not verified]

29. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e278S-e325S.

30. Raja S, Idrees JJ, Blackstone EH, et al. Routine venous thromboembolism screening after pneumonectomy: the more you look, the more you see. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):524-532.e2.

31. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225.

32. Naidu SS, Aronow HD, Box LC, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement: 2016 best practices in the cardiac catheterization laboratory:(endorsed by the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencionista; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(3):407-423.

33. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. JACC. 2011;58(24):e44-e122.

34. Mason PJ, Shah B, Tamis-Holland JE, et al; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine. AHA scientific statement: an update on radial artery access and best practices for transradial coronary angiography and intervention in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(9):e000035.

35. Rao SV, Tremmel JA, Gilchrist IC, et al; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention’s Transradial Working Group. Best practices for transradial angiography and intervention: a consensus statement from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions’ transradial working group. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(2):228-236. 36. Moran JE, Ash SR. Locking solutions for hemodialysis catheters; heparin and citrate: a position paper by ASDIN. Semin Dial. 2008;21(5):490-492.

1. Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119(1):64S-94S.

2. Bipartisan E&C leaders request FDA briefing on threat to U.S. heparin supply [press release]. Washington, DC: House Committee on Energy and Commerce; July 30, 2019. https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/bipartisan-ec-leaders-request-fda-briefing-on-threat-to-us-heparin-supply. Accessed September 19, 2019.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages. Heparin injection. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortages-List?page=CurrentShortages. Accessed September 19, 2019.

4. Reed BN, Fox ER, Konig M, et al. The impact of drug shortages on patients with cardiovascular disease: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am Heart J. 2016;175:130-141.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, VISN Pharmacist Executives, The Center For Medication Safety. Heparin supply status: frequently asked questions. PBM-2018-02. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/vacenterformedicationsafety/HeparinandSalineSyringeRecallDuetoContamination_NationalPBMPati.pdf. Published May 3, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

6. Shore-Lesserson I, Baker RA, Ferraris VA, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines-anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):650-662.

7. Soroka S, Agharazii M, Donnelly S, et al. An adjustable dalteparin sodium dose regimen for the prevention of clotting in the extracorporeal circuit in hemodialysis: a clinical trial of safety and efficacy (the PARROT Study). Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1-12.

8. Shantha GPS, Kumar AA, Sethi M, Khanna RC, Pancholy SB. Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin compared to unfractionated heparin for chronic outpatient hemodialysis in end stage renal disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Peer J. 2015;3:e835.

9. Kessler M, Moureau F, and Nguyen P. Anticoagulation in chronic hemodialysis: progress toward an optimal approach. Semin Dial. 2015;28(5):474-489.

10. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e227s-e277S.

11. Kaye AD, Brunk AJ, Kaye AJ, et al. Regional anesthesia in patients on anticoagulation therapies—evidence-based recommendations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(9):67.

12. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e195S-e226S.

13. Naylor AR, Ricco JB, de Borst GJ, et al. Management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease: 2017 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:3-81.

14. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2017;69(11): e71-e126.

15. Bjorck M, Koelemaya M, Acosta S, et al. Management of diseases of mesenteric arteries and veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53(4):460-510.

16. Gorski L, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, McGoldrick M, Orr M, Doellman D. Infusion therapy standards of practice. J Infusion Nurs. 2016;39:S1-S156.

17. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(10):e275-e444.

18. Spyropoulos AC, Al-Badri A, Sherwood MW, Douketis JD. Periprocedural management of patients receiving a vitamin K antagonist or a direct oral anticoagulant requiring an elective procedure or surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(5):875-885.

, . Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation. 2012;126(4):486-490.

20. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e326S-e350S.

21. Sousa-Uva M, Neumann F-J, Ahlsson A, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with a special contribution of the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55(1):4-90.

22. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

23. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

24. Angiomax [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: The Medicines Company; March 2016.

25. Sousa-Uva, Head SJ, Milojevic M, et al. 2017 EACTS guidelines on perioperative medication in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53(1):5-33.

26. Witt DM, Nieuwlaat R, Clark NP, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for the management of venous thromboembolism: optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018: 2(22):3257-3291

27. Kearon C, Akl EA, Blaivas A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

28. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Manager Service. Direct oral anticoagulants criteria for use and algorithm for venous thromboembolism treatment. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/criteriaforuse.asp. Updated December 2016. [Source not verified]

29. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e278S-e325S.

30. Raja S, Idrees JJ, Blackstone EH, et al. Routine venous thromboembolism screening after pneumonectomy: the more you look, the more you see. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):524-532.e2.

31. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225.

32. Naidu SS, Aronow HD, Box LC, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement: 2016 best practices in the cardiac catheterization laboratory:(endorsed by the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencionista; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d’intervention). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(3):407-423.

33. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. JACC. 2011;58(24):e44-e122.

34. Mason PJ, Shah B, Tamis-Holland JE, et al; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine. AHA scientific statement: an update on radial artery access and best practices for transradial coronary angiography and intervention in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(9):e000035.

35. Rao SV, Tremmel JA, Gilchrist IC, et al; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention’s Transradial Working Group. Best practices for transradial angiography and intervention: a consensus statement from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions’ transradial working group. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(2):228-236. 36. Moran JE, Ash SR. Locking solutions for hemodialysis catheters; heparin and citrate: a position paper by ASDIN. Semin Dial. 2008;21(5):490-492.