User login

Disposable Navigation for Total Knee Arthroplasty

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) continues to be a widely utilized treatment option for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, and the number of patients undergoing TKA is projected to continually increase over the next decade.1 Although TKA is highly successful for many patients, studies continue to report that approximately 20% of patients are dissatisfied after undergoing TKA, and nearly 25% of knee revisions are performed for instability or malalignment.2,3 Technological advances have been developed to help improve clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. Over the past decade, computer navigation and intraoperative guides have been introduced to help control surgical variables and overcome the limitations and inaccuracies of traditional mechanical instrumentation. Currently, there are a variety of technologies available to assist surgeons with component alignment, including extramedullary devices, computer-assisted navigation systems (CAS), and patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) that help achieve desired alignment goals.4,5

Computer-assisted navigation tools were introduced in an effort to improve implant alignment and clinical outcomes compared to traditional mechanical guides. Some argue that the use of computer-assisted surgery has a steep learning curve and successful use is dependent on the user’s experience; however, studies have suggested computer-assisted surgery may allow less experienced surgeons to reliably achieve anticipated intraoperative alignment goals with a low complication rate.6,7 Various studies have looked at computer-assisted TKA at short to mid-term follow-up, but few studies have reported long-term outcomes.6-9 de Steiger and colleagues10 recently found that computer-assisted TKA reduced the overall revision rate for aseptic loosening following TKA in patients younger than age 65 years, which suggests benefit of CAS for younger patients. Short-term follow-up has also shown the benefit of CAS TKA in patients with severe extra-articular deformity, where traditional instrumentation cannot be utilized.11 Currently, there is no consensus that computer-assisted TKA leads to improved postoperative patient reported outcomes, because many studies are limited by study design or small cohorts; however, current literature does show an improvement in component alignment as compared to mechanical instrumentation.9,12,13 As future implant and position targets are defined to improve implant survivorship and clinical outcomes in total joint arthroplasty, computer-assisted devices will be useful to help achieve more precise and accurate component positioning.

In addition to CAS devices, some companies have sought to improve TKA surgery by introducing PSI. PSI was introduced to improve component alignment in TKA, with the purported advantages of a shorter surgical time, decrease in the number of instruments needed, and improved clinical outcomes. PSI accuracy remains variable, which may be attributed to the various systems and implant designs in each study.14-17 In addition, advanced preoperative imaging is necessary, which further adds to the overall cost.17 While the recent advancement in technology may provide decreased costs at the time of surgery, the increased cost and time incurred by the patient preoperatively has not resulted in significantly better clinical outcomes.18,19 Additionally, recent work has not shown PSI to have superior accuracy as compared to currently available CAS devices.14 These findings suggest that the additional cost and time incurred by patients may limit the widespread use of PSI.

Although computer navigation has been shown to be more accurate than conventional instrumentation and PSI, the lack of improvement in long-term clinical outcome data has limited its use. In a meta-analysis, Bauwens and colleagues20 suggested that while navigated TKAs have improved component alignment outcomes as compared to conventional surgery, the clinical benefit remains unclear. Less than 5% of surgeons are currently using navigation systems due to the perceived learning curve, cost, additional surgical time, and imaging required to utilize these systems. Certain navigation systems can be seemingly cumbersome, with large consoles, increased number of instruments required, and optical instruments with line-of-sight issues. Recent technological advances have worked to decrease this challenge by using accelerometer- and gyroscope-based electronic components, which combine the accuracy of computer-assisted technology with the ease of use of mechanical guides.

Accelerometer and gyroscope technology systems, such as the iAssist system, are portable devices that do not require a large computer console or navigation arrays. This technology relies on accelerator-based navigation without additional preoperative imaging. A recent study demonstrated the iAssist had reproducible accuracy in component alignment that could be easily incorporated into the operating room without optical trackers.21 The use of portable computer-assisted devices provides a more compact and easily accessible technology that can be used to achieve accurate component alignment without additional large equipment in the operating room.22 These new handheld intraoperative tools have been introduced to place implants according to a preoperative plan in order to minimize failure due to preoperative extra-articular deformity or intraoperative technical miscues.23 Nam and colleagues24 used an accelerometer-based surgical navigation system to perform tibial resections in cadaveric models, and found that the accelerometer-based guide was accurate for tibial resection in both the coronal and sagittal planes. In a prospective randomized controlled trial evaluating 100 patients undergoing a TKA using either an accelerometer-based guide or conventional alignment methods, the authors showed that the accelerometer-based guide decreased outliers in tibial component alignment compared to conventional guides.25 In the accelerometer-based guide cohort, 95.7% of tibial components were within 2° of perpendicular to the tibial mechanical axis, compared to 68.1% in the conventional group (P < .001). These results suggested that portable accelerometer-based navigation allows surgeons to achieve satisfactory tibial component alignment with a decrease in the number of potential outliers.24,25 Similarly, Bugbee and colleagues26 found that accelerometer-based handheld navigation was accurate for tibial coronal and sagittal alignment and no additional surgical time was required compared to conventional techniques.

The relationship between knee alignment and clinical outcomes for TKA remains controversial. Regardless of the surgeon’s alignment preference, it is important to reliably and accurately execute the preoperative plan in a reproducible fashion. Advances in technology that assist with intraoperative component alignment can be useful, and may help decrease the incidence of implant malalignment in clinical practice.

Preoperative Planning and Intraoperative Technique

Preoperative planning is carried out in a manner identical to the use of conventional mechanical guides. Long leg films are taken for evaluation of overall limb alignment, and calibrated lateral images are taken for templating implant sizes. Lines are drawn on the images to determine the difference between the mechanical and anatomic axis of the femur, and a line drawn perpendicular to the mechanical axis is placed to show the expected bone cut. In similar fashion a perpendicular line to the tibial mechanical axis is also drawn to show the expected tibial resection. This preoperative plan allows the surgeon to have an additional intraoperative guide to ensure accuracy of the computer-assisted device.

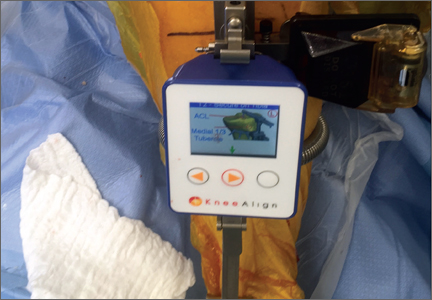

After standard exposure, the distal femoral or proximal tibial cut can be made based on surgeon preference. The system being demonstrated in the accompanying photos is the KneeAlign 2 system (OrthAlign).

Distal Femoral Cut

The KneeAlign 2 femoral cutting guide is attached to the distal femur with a central pin that is placed in the middle of the distal femur measured from medial to lateral, and 1 cm anterior to the intercondylar notch. It is important to note that this spot is often more medial than traditionally used for insertion of an intramedullary rod. This central point sets the distal point of the femoral mechanical axis. The device is then held in place with 2 oblique pins, and is solidly fixed to the bone. Using a rotating motion, the femur is rotated around the hip joint. The accelerometer and gyroscope in the unit are able to determine the center of the hip joint from this motion, creating the proximal point of the mechanical axis of the femur. Once the mechanical axis of the femur is determined, varus/valgus and flexion/extension can be adjusted on the guide. One adjustment screw is available for varus/valgus, and a second is available for flexion/extension. Numbers on the device screen show real-time alignment, and are easily adjusted to set the desired alignment (Figure 1). Once alignment is obtained, a mechanical stylus is used to determine depth of resection, and the distal femoral cutting block is pinned. After pinning the block, the 3 pins in the device are removed, and the device is removed from the bone. This leaves only the distal femoral cutting block in place. In experienced hands, this part of the procedure takes less than 3 minutes.

Proximal Tibial Cut

The KneeAlign 2 proximal tibial guide is similar in appearance to a standard mechanical tibial cutting guide. It is attached to the proximal tibia with a spring around the calf and 2 pins that hold the device aligned with the medial third of the tibial tubercle. A stylus is then centered on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) footprint, which sets the proximal mechanical axis point of the tibia (Figure 2). An offset number is read off the stylus on the ACL footprint, and this number is matched on the ankle offset portion of the guide. The device has 2 sensors. One sensor is on the chassis of the device, and the other is on a mobile arm. Movements between the 2 are monitored by the accelerometers, allowing for accurate maintenance of alignment position even with motion in the leg. A point is taken from the lateral malleolus and then a second point is taken from the medial malleolus. These points are used to determine the center of the ankle joint, which sets the distal mechanical axis point. Once mechanical axis of the tibia is determined, the tibial cutting guide is pinned in place, and can be adjusted with real-time guidance of the varus/valgus and posterior slope values seen on the device (Figure 3). Cut depth is once again determined with a mechanical stylus.

Limitations

Although these devices have proven to be very accurate, surgeons must continue to recognize that all tools can have errors. With computerized guides of any sort, these errors are usually user errors that cannot be detected by the device. Surgeons need to be able to recognize this and always double-check bone cuts for accuracy. Templating the bone cuts prior to surgery is an effective double-check. In addition, many handheld accelerometer devices do not currently assist with the rotational alignment of the femoral component. This is still performed using the surgeon’s preferred technique, and is a limitation of these systems.

Discussion

Currently, TKA provides satisfactory 10-year results with modern implant designs and survival rates as high as 90% to 95%.27,28 Even with good survival rates, a percentage of patients fail within the first 5 years.3 At a single institution, 50% of revision TKAs were related to instability, malalignment, or failure of fixation that occurred less than 2 years after the index procedure.29 In general, TKA with mechanical instrumentation provides satisfactory pain relief and postoperative knee function; however, studies have consistently shown that the use of advanced technology decreases the risk of implant malalignment, which may decrease early implant failure rates as compared to mechanical and some PSI.13,14,22 While there is a paucity of literature that has shown better clinical outcomes with the use of advanced technology, there are studies supporting the notion that proper limb alignment and component positioning improves implant survivorship.23,30

CAS may have additional advantages if the surgeon chooses to place the TKA in an alignment other than a neutral mechanical axis. Kinematic alignment for TKA has gained increasing popularity, where the target of a neutral mechanical axis alignment is not always the goal.31,32 The reported benefit is a more natural ligament tension with the hope of improving patient satisfaction. One concern with this technique is that it is a departure from the long-held teaching that a TKA aligned to a neutral mechanical axis is necessary for long-term implant survivorship.33,34 In addition, if the goal of surgery is to cut the tibia and femur at a specific varus/valgus cut, standard instrumentation may not allow for this level of accuracy. This in turn increases the risk of having a tibial or femoral cut that is outside the commonly accepted standards of alignment, which may lead to early implant failure. If further research suggests alignment is a variable that differs from patient to patient, the use of precise tools to ensure accuracy of executing the preoperatively templated alignment becomes even more important.

As the number of TKAs continues to rise each year, even a small percentage of malaligned knees that go on to revision surgery will create a large burden on the healthcare system.1,3 Although the short-term clinical benefits of CAS have not shown substantial differences as compared to conventional TKA, the number of knees aligned outside of a desired neutral mechanical axis alignment has been shown in multiple studies to be decreased with the use of advanced technology.7,12,34 Although CAS is an additional cost to a primary TKA, if the orthopedic community can decrease the number of TKA revisions due to malalignment from 6.6% to nearly zero, this may decrease the revision burden and overall cost to the healthcare system.1,3

TKA technology continues to evolve, and we must continue to assess each new advance not only to understand how it works, but also to ensure it addresses a specific clinical problem, and to be aware of the costs associated before incorporating it into routine practice. Some argue that the use of advanced technology requires increased surgical time, which in turn ultimately increases costs; however, one study has documented no increase in surgical time with handheld navigation while maintaining the accuracy of the device.34 In addition, no significant radiographic or clinical differences have been found between handheld navigation and larger console CAS systems, but large console systems have been associated with increased surgical times.22 The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides has proven to provide reliable coronal and sagittal implant alignment that can easily be incorporated into the operating room. More widespread use of such technology will help decrease alignment outliers for TKA, and future long-term clinical outcome studies will be necessary to assess functional outcomes.

Conclusion

Advanced computer based technology offers an additional tool to the surgeon for reliably improving component positioning during TKA. The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides increases the accuracy of component placement while decreasing the incidence of outliers compared to standard mechanical guides, without the need for a large computer console. Long-term radiographic and patient-reported outcomes are necessary to further validate these devices.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57-63.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28( 8 Suppl):116-119.

4. Sassoon A, Nam D, Nunley R, Barrack R. Systematic review of patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: new but not improved. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):151-158.

5. Anderson KC, Buehler KC, Markel DC. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: comparison with conventional methods. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3):132-138.

6. Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1097-1106.

7. Khakha RS, Chowdhry M, Sivaprakasam M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Radiological and functional outcomes in computer assisted total knee arthroplasty between consultants and trainees - a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(8):1344-1347.

8. Zhu M, Ang CL, Yeo SJ, Lo NN, Chia SL, Chong HC. Minimally invasive computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty compared with conventional total knee arthroplasty: a prospective 9-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Roberts TD, Clatworthy MG, Frampton CM, Young SW. Does computer assisted navigation improve functional outcomes and implant survivability after total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):59-63.

10. de Steiger RN, Liu YL, Graves SE. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(8):635-642.

11. Fehring TK, Mason JB, Moskal J, Pollock DC, Mann J, Williams VJ. When computer-assisted knee replacement is the best alternative. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:132-136.

12. Iorio R, Mazza D, Drogo P, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of an accelerometer-based system for the tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39(3):461-466.

13. Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A. Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:152-159.

14. Ollivier M, Tribot-Laspiere Q, Amzallag J, Boisrenoult P, Pujol N, Beaufils P. Abnormal rate of intraoperative and postoperative implant positioning outliers using “MRI-based patient-specific” compared to “computer assisted” instrumentation in total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

15. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Zhu J, Ruh EL, Howell SM, Barrack RL. Do patient-specific guides improve coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):895-902.

16. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Ruh EL, et al. Are patient-specific cutting blocks cost-effective for total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):889-894.

17. Barrack RL, Ruh EL, Williams BM, Ford AD, Foreman K, Nunley RM. Patient specific cutting blocks are currently of no proven value. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):95-99.

18. Chen JY, Chin PL, Tay DK, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Functional outcome and quality of life after patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(10):1724-1728.

19. Goyal N, Patel AR, Yaffe MA, Luo MY, Stulberg SD. Does implant design influence the accuracy of patient specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1526-1530.

20. Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, et al. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):261-269.

21. Scuderi GR, Fallaha M, Masse V, Lavigne P, Amiot LP, Berthiaume MJ. Total knee arthroplasty with a novel navigation system within the surgical field. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):167-173.

22. Goh GS, Liow MH, Lim WS, Tay DK, Yeo SJ, Tan MH. Accelerometer-based navigation is as accurate as optical computer navigation in restoring the joint line and mechanical axis after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective matched study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1):92-97.

23. Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Liberal indications for minimally invasive oxford unicondylar arthroplasty provide rapid functional recovery and pain relief. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:193-197.

24. Nam D, Jerabek SA, Cross MB, Mayman DJ. Cadaveric analysis of an accelerometer-based portable navigation device for distal femoral cutting block alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Comput Aided Surg. 2012;17(4):205-210.

25. Nam D, Cody EA, Nguyen JT, Figgie MP, Mayman DJ. Extramedullary guides versus portable, accelerometer-based navigation for tibial alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial: winner of the 2013 HAP PAUL award. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):288-294.

26. Bugbee WD, Kermanshahi AY, Munro MM, McCauley JC, Copp SN. Accuracy of a hand-held surgical navigation system for tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(6):1225-1228.

27. Schai PA, Thornhill TS, Scott RD. Total knee arthroplasty with the PFC system. Results at a minimum of ten years and survivorship analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(5):850-858.

28. Pradhan NR, Gambhir A, Porter ML. Survivorship analysis of 3234 primary knee arthroplasties implanted over a 26-year period: a study of eight different implant designs. Knee. 2006;13(1):7-11.

29. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

30. Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):39-43.

31. Cherian JJ, Kapadia BH, Banerjee S, Jauregui JJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Mechanical, anatomical, and kinematic axis in TKA: concepts and practical applications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(2):89-95.

32. Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik K, Ghaly LR, Hull ML. Does varus alignment adversely affect implant survival and function six years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? Int Orthop. 2015;39(11):2117-2124.

33. Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153-156.

34. Huang EH, Copp SN, Bugbee WD. Accuracy of a handheld accelerometer-based navigation system for femoral and tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(11):1906-1910.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) continues to be a widely utilized treatment option for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, and the number of patients undergoing TKA is projected to continually increase over the next decade.1 Although TKA is highly successful for many patients, studies continue to report that approximately 20% of patients are dissatisfied after undergoing TKA, and nearly 25% of knee revisions are performed for instability or malalignment.2,3 Technological advances have been developed to help improve clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. Over the past decade, computer navigation and intraoperative guides have been introduced to help control surgical variables and overcome the limitations and inaccuracies of traditional mechanical instrumentation. Currently, there are a variety of technologies available to assist surgeons with component alignment, including extramedullary devices, computer-assisted navigation systems (CAS), and patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) that help achieve desired alignment goals.4,5

Computer-assisted navigation tools were introduced in an effort to improve implant alignment and clinical outcomes compared to traditional mechanical guides. Some argue that the use of computer-assisted surgery has a steep learning curve and successful use is dependent on the user’s experience; however, studies have suggested computer-assisted surgery may allow less experienced surgeons to reliably achieve anticipated intraoperative alignment goals with a low complication rate.6,7 Various studies have looked at computer-assisted TKA at short to mid-term follow-up, but few studies have reported long-term outcomes.6-9 de Steiger and colleagues10 recently found that computer-assisted TKA reduced the overall revision rate for aseptic loosening following TKA in patients younger than age 65 years, which suggests benefit of CAS for younger patients. Short-term follow-up has also shown the benefit of CAS TKA in patients with severe extra-articular deformity, where traditional instrumentation cannot be utilized.11 Currently, there is no consensus that computer-assisted TKA leads to improved postoperative patient reported outcomes, because many studies are limited by study design or small cohorts; however, current literature does show an improvement in component alignment as compared to mechanical instrumentation.9,12,13 As future implant and position targets are defined to improve implant survivorship and clinical outcomes in total joint arthroplasty, computer-assisted devices will be useful to help achieve more precise and accurate component positioning.

In addition to CAS devices, some companies have sought to improve TKA surgery by introducing PSI. PSI was introduced to improve component alignment in TKA, with the purported advantages of a shorter surgical time, decrease in the number of instruments needed, and improved clinical outcomes. PSI accuracy remains variable, which may be attributed to the various systems and implant designs in each study.14-17 In addition, advanced preoperative imaging is necessary, which further adds to the overall cost.17 While the recent advancement in technology may provide decreased costs at the time of surgery, the increased cost and time incurred by the patient preoperatively has not resulted in significantly better clinical outcomes.18,19 Additionally, recent work has not shown PSI to have superior accuracy as compared to currently available CAS devices.14 These findings suggest that the additional cost and time incurred by patients may limit the widespread use of PSI.

Although computer navigation has been shown to be more accurate than conventional instrumentation and PSI, the lack of improvement in long-term clinical outcome data has limited its use. In a meta-analysis, Bauwens and colleagues20 suggested that while navigated TKAs have improved component alignment outcomes as compared to conventional surgery, the clinical benefit remains unclear. Less than 5% of surgeons are currently using navigation systems due to the perceived learning curve, cost, additional surgical time, and imaging required to utilize these systems. Certain navigation systems can be seemingly cumbersome, with large consoles, increased number of instruments required, and optical instruments with line-of-sight issues. Recent technological advances have worked to decrease this challenge by using accelerometer- and gyroscope-based electronic components, which combine the accuracy of computer-assisted technology with the ease of use of mechanical guides.

Accelerometer and gyroscope technology systems, such as the iAssist system, are portable devices that do not require a large computer console or navigation arrays. This technology relies on accelerator-based navigation without additional preoperative imaging. A recent study demonstrated the iAssist had reproducible accuracy in component alignment that could be easily incorporated into the operating room without optical trackers.21 The use of portable computer-assisted devices provides a more compact and easily accessible technology that can be used to achieve accurate component alignment without additional large equipment in the operating room.22 These new handheld intraoperative tools have been introduced to place implants according to a preoperative plan in order to minimize failure due to preoperative extra-articular deformity or intraoperative technical miscues.23 Nam and colleagues24 used an accelerometer-based surgical navigation system to perform tibial resections in cadaveric models, and found that the accelerometer-based guide was accurate for tibial resection in both the coronal and sagittal planes. In a prospective randomized controlled trial evaluating 100 patients undergoing a TKA using either an accelerometer-based guide or conventional alignment methods, the authors showed that the accelerometer-based guide decreased outliers in tibial component alignment compared to conventional guides.25 In the accelerometer-based guide cohort, 95.7% of tibial components were within 2° of perpendicular to the tibial mechanical axis, compared to 68.1% in the conventional group (P < .001). These results suggested that portable accelerometer-based navigation allows surgeons to achieve satisfactory tibial component alignment with a decrease in the number of potential outliers.24,25 Similarly, Bugbee and colleagues26 found that accelerometer-based handheld navigation was accurate for tibial coronal and sagittal alignment and no additional surgical time was required compared to conventional techniques.

The relationship between knee alignment and clinical outcomes for TKA remains controversial. Regardless of the surgeon’s alignment preference, it is important to reliably and accurately execute the preoperative plan in a reproducible fashion. Advances in technology that assist with intraoperative component alignment can be useful, and may help decrease the incidence of implant malalignment in clinical practice.

Preoperative Planning and Intraoperative Technique

Preoperative planning is carried out in a manner identical to the use of conventional mechanical guides. Long leg films are taken for evaluation of overall limb alignment, and calibrated lateral images are taken for templating implant sizes. Lines are drawn on the images to determine the difference between the mechanical and anatomic axis of the femur, and a line drawn perpendicular to the mechanical axis is placed to show the expected bone cut. In similar fashion a perpendicular line to the tibial mechanical axis is also drawn to show the expected tibial resection. This preoperative plan allows the surgeon to have an additional intraoperative guide to ensure accuracy of the computer-assisted device.

After standard exposure, the distal femoral or proximal tibial cut can be made based on surgeon preference. The system being demonstrated in the accompanying photos is the KneeAlign 2 system (OrthAlign).

Distal Femoral Cut

The KneeAlign 2 femoral cutting guide is attached to the distal femur with a central pin that is placed in the middle of the distal femur measured from medial to lateral, and 1 cm anterior to the intercondylar notch. It is important to note that this spot is often more medial than traditionally used for insertion of an intramedullary rod. This central point sets the distal point of the femoral mechanical axis. The device is then held in place with 2 oblique pins, and is solidly fixed to the bone. Using a rotating motion, the femur is rotated around the hip joint. The accelerometer and gyroscope in the unit are able to determine the center of the hip joint from this motion, creating the proximal point of the mechanical axis of the femur. Once the mechanical axis of the femur is determined, varus/valgus and flexion/extension can be adjusted on the guide. One adjustment screw is available for varus/valgus, and a second is available for flexion/extension. Numbers on the device screen show real-time alignment, and are easily adjusted to set the desired alignment (Figure 1). Once alignment is obtained, a mechanical stylus is used to determine depth of resection, and the distal femoral cutting block is pinned. After pinning the block, the 3 pins in the device are removed, and the device is removed from the bone. This leaves only the distal femoral cutting block in place. In experienced hands, this part of the procedure takes less than 3 minutes.

Proximal Tibial Cut

The KneeAlign 2 proximal tibial guide is similar in appearance to a standard mechanical tibial cutting guide. It is attached to the proximal tibia with a spring around the calf and 2 pins that hold the device aligned with the medial third of the tibial tubercle. A stylus is then centered on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) footprint, which sets the proximal mechanical axis point of the tibia (Figure 2). An offset number is read off the stylus on the ACL footprint, and this number is matched on the ankle offset portion of the guide. The device has 2 sensors. One sensor is on the chassis of the device, and the other is on a mobile arm. Movements between the 2 are monitored by the accelerometers, allowing for accurate maintenance of alignment position even with motion in the leg. A point is taken from the lateral malleolus and then a second point is taken from the medial malleolus. These points are used to determine the center of the ankle joint, which sets the distal mechanical axis point. Once mechanical axis of the tibia is determined, the tibial cutting guide is pinned in place, and can be adjusted with real-time guidance of the varus/valgus and posterior slope values seen on the device (Figure 3). Cut depth is once again determined with a mechanical stylus.

Limitations

Although these devices have proven to be very accurate, surgeons must continue to recognize that all tools can have errors. With computerized guides of any sort, these errors are usually user errors that cannot be detected by the device. Surgeons need to be able to recognize this and always double-check bone cuts for accuracy. Templating the bone cuts prior to surgery is an effective double-check. In addition, many handheld accelerometer devices do not currently assist with the rotational alignment of the femoral component. This is still performed using the surgeon’s preferred technique, and is a limitation of these systems.

Discussion

Currently, TKA provides satisfactory 10-year results with modern implant designs and survival rates as high as 90% to 95%.27,28 Even with good survival rates, a percentage of patients fail within the first 5 years.3 At a single institution, 50% of revision TKAs were related to instability, malalignment, or failure of fixation that occurred less than 2 years after the index procedure.29 In general, TKA with mechanical instrumentation provides satisfactory pain relief and postoperative knee function; however, studies have consistently shown that the use of advanced technology decreases the risk of implant malalignment, which may decrease early implant failure rates as compared to mechanical and some PSI.13,14,22 While there is a paucity of literature that has shown better clinical outcomes with the use of advanced technology, there are studies supporting the notion that proper limb alignment and component positioning improves implant survivorship.23,30

CAS may have additional advantages if the surgeon chooses to place the TKA in an alignment other than a neutral mechanical axis. Kinematic alignment for TKA has gained increasing popularity, where the target of a neutral mechanical axis alignment is not always the goal.31,32 The reported benefit is a more natural ligament tension with the hope of improving patient satisfaction. One concern with this technique is that it is a departure from the long-held teaching that a TKA aligned to a neutral mechanical axis is necessary for long-term implant survivorship.33,34 In addition, if the goal of surgery is to cut the tibia and femur at a specific varus/valgus cut, standard instrumentation may not allow for this level of accuracy. This in turn increases the risk of having a tibial or femoral cut that is outside the commonly accepted standards of alignment, which may lead to early implant failure. If further research suggests alignment is a variable that differs from patient to patient, the use of precise tools to ensure accuracy of executing the preoperatively templated alignment becomes even more important.

As the number of TKAs continues to rise each year, even a small percentage of malaligned knees that go on to revision surgery will create a large burden on the healthcare system.1,3 Although the short-term clinical benefits of CAS have not shown substantial differences as compared to conventional TKA, the number of knees aligned outside of a desired neutral mechanical axis alignment has been shown in multiple studies to be decreased with the use of advanced technology.7,12,34 Although CAS is an additional cost to a primary TKA, if the orthopedic community can decrease the number of TKA revisions due to malalignment from 6.6% to nearly zero, this may decrease the revision burden and overall cost to the healthcare system.1,3

TKA technology continues to evolve, and we must continue to assess each new advance not only to understand how it works, but also to ensure it addresses a specific clinical problem, and to be aware of the costs associated before incorporating it into routine practice. Some argue that the use of advanced technology requires increased surgical time, which in turn ultimately increases costs; however, one study has documented no increase in surgical time with handheld navigation while maintaining the accuracy of the device.34 In addition, no significant radiographic or clinical differences have been found between handheld navigation and larger console CAS systems, but large console systems have been associated with increased surgical times.22 The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides has proven to provide reliable coronal and sagittal implant alignment that can easily be incorporated into the operating room. More widespread use of such technology will help decrease alignment outliers for TKA, and future long-term clinical outcome studies will be necessary to assess functional outcomes.

Conclusion

Advanced computer based technology offers an additional tool to the surgeon for reliably improving component positioning during TKA. The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides increases the accuracy of component placement while decreasing the incidence of outliers compared to standard mechanical guides, without the need for a large computer console. Long-term radiographic and patient-reported outcomes are necessary to further validate these devices.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) continues to be a widely utilized treatment option for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, and the number of patients undergoing TKA is projected to continually increase over the next decade.1 Although TKA is highly successful for many patients, studies continue to report that approximately 20% of patients are dissatisfied after undergoing TKA, and nearly 25% of knee revisions are performed for instability or malalignment.2,3 Technological advances have been developed to help improve clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. Over the past decade, computer navigation and intraoperative guides have been introduced to help control surgical variables and overcome the limitations and inaccuracies of traditional mechanical instrumentation. Currently, there are a variety of technologies available to assist surgeons with component alignment, including extramedullary devices, computer-assisted navigation systems (CAS), and patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) that help achieve desired alignment goals.4,5

Computer-assisted navigation tools were introduced in an effort to improve implant alignment and clinical outcomes compared to traditional mechanical guides. Some argue that the use of computer-assisted surgery has a steep learning curve and successful use is dependent on the user’s experience; however, studies have suggested computer-assisted surgery may allow less experienced surgeons to reliably achieve anticipated intraoperative alignment goals with a low complication rate.6,7 Various studies have looked at computer-assisted TKA at short to mid-term follow-up, but few studies have reported long-term outcomes.6-9 de Steiger and colleagues10 recently found that computer-assisted TKA reduced the overall revision rate for aseptic loosening following TKA in patients younger than age 65 years, which suggests benefit of CAS for younger patients. Short-term follow-up has also shown the benefit of CAS TKA in patients with severe extra-articular deformity, where traditional instrumentation cannot be utilized.11 Currently, there is no consensus that computer-assisted TKA leads to improved postoperative patient reported outcomes, because many studies are limited by study design or small cohorts; however, current literature does show an improvement in component alignment as compared to mechanical instrumentation.9,12,13 As future implant and position targets are defined to improve implant survivorship and clinical outcomes in total joint arthroplasty, computer-assisted devices will be useful to help achieve more precise and accurate component positioning.

In addition to CAS devices, some companies have sought to improve TKA surgery by introducing PSI. PSI was introduced to improve component alignment in TKA, with the purported advantages of a shorter surgical time, decrease in the number of instruments needed, and improved clinical outcomes. PSI accuracy remains variable, which may be attributed to the various systems and implant designs in each study.14-17 In addition, advanced preoperative imaging is necessary, which further adds to the overall cost.17 While the recent advancement in technology may provide decreased costs at the time of surgery, the increased cost and time incurred by the patient preoperatively has not resulted in significantly better clinical outcomes.18,19 Additionally, recent work has not shown PSI to have superior accuracy as compared to currently available CAS devices.14 These findings suggest that the additional cost and time incurred by patients may limit the widespread use of PSI.

Although computer navigation has been shown to be more accurate than conventional instrumentation and PSI, the lack of improvement in long-term clinical outcome data has limited its use. In a meta-analysis, Bauwens and colleagues20 suggested that while navigated TKAs have improved component alignment outcomes as compared to conventional surgery, the clinical benefit remains unclear. Less than 5% of surgeons are currently using navigation systems due to the perceived learning curve, cost, additional surgical time, and imaging required to utilize these systems. Certain navigation systems can be seemingly cumbersome, with large consoles, increased number of instruments required, and optical instruments with line-of-sight issues. Recent technological advances have worked to decrease this challenge by using accelerometer- and gyroscope-based electronic components, which combine the accuracy of computer-assisted technology with the ease of use of mechanical guides.

Accelerometer and gyroscope technology systems, such as the iAssist system, are portable devices that do not require a large computer console or navigation arrays. This technology relies on accelerator-based navigation without additional preoperative imaging. A recent study demonstrated the iAssist had reproducible accuracy in component alignment that could be easily incorporated into the operating room without optical trackers.21 The use of portable computer-assisted devices provides a more compact and easily accessible technology that can be used to achieve accurate component alignment without additional large equipment in the operating room.22 These new handheld intraoperative tools have been introduced to place implants according to a preoperative plan in order to minimize failure due to preoperative extra-articular deformity or intraoperative technical miscues.23 Nam and colleagues24 used an accelerometer-based surgical navigation system to perform tibial resections in cadaveric models, and found that the accelerometer-based guide was accurate for tibial resection in both the coronal and sagittal planes. In a prospective randomized controlled trial evaluating 100 patients undergoing a TKA using either an accelerometer-based guide or conventional alignment methods, the authors showed that the accelerometer-based guide decreased outliers in tibial component alignment compared to conventional guides.25 In the accelerometer-based guide cohort, 95.7% of tibial components were within 2° of perpendicular to the tibial mechanical axis, compared to 68.1% in the conventional group (P < .001). These results suggested that portable accelerometer-based navigation allows surgeons to achieve satisfactory tibial component alignment with a decrease in the number of potential outliers.24,25 Similarly, Bugbee and colleagues26 found that accelerometer-based handheld navigation was accurate for tibial coronal and sagittal alignment and no additional surgical time was required compared to conventional techniques.

The relationship between knee alignment and clinical outcomes for TKA remains controversial. Regardless of the surgeon’s alignment preference, it is important to reliably and accurately execute the preoperative plan in a reproducible fashion. Advances in technology that assist with intraoperative component alignment can be useful, and may help decrease the incidence of implant malalignment in clinical practice.

Preoperative Planning and Intraoperative Technique

Preoperative planning is carried out in a manner identical to the use of conventional mechanical guides. Long leg films are taken for evaluation of overall limb alignment, and calibrated lateral images are taken for templating implant sizes. Lines are drawn on the images to determine the difference between the mechanical and anatomic axis of the femur, and a line drawn perpendicular to the mechanical axis is placed to show the expected bone cut. In similar fashion a perpendicular line to the tibial mechanical axis is also drawn to show the expected tibial resection. This preoperative plan allows the surgeon to have an additional intraoperative guide to ensure accuracy of the computer-assisted device.

After standard exposure, the distal femoral or proximal tibial cut can be made based on surgeon preference. The system being demonstrated in the accompanying photos is the KneeAlign 2 system (OrthAlign).

Distal Femoral Cut

The KneeAlign 2 femoral cutting guide is attached to the distal femur with a central pin that is placed in the middle of the distal femur measured from medial to lateral, and 1 cm anterior to the intercondylar notch. It is important to note that this spot is often more medial than traditionally used for insertion of an intramedullary rod. This central point sets the distal point of the femoral mechanical axis. The device is then held in place with 2 oblique pins, and is solidly fixed to the bone. Using a rotating motion, the femur is rotated around the hip joint. The accelerometer and gyroscope in the unit are able to determine the center of the hip joint from this motion, creating the proximal point of the mechanical axis of the femur. Once the mechanical axis of the femur is determined, varus/valgus and flexion/extension can be adjusted on the guide. One adjustment screw is available for varus/valgus, and a second is available for flexion/extension. Numbers on the device screen show real-time alignment, and are easily adjusted to set the desired alignment (Figure 1). Once alignment is obtained, a mechanical stylus is used to determine depth of resection, and the distal femoral cutting block is pinned. After pinning the block, the 3 pins in the device are removed, and the device is removed from the bone. This leaves only the distal femoral cutting block in place. In experienced hands, this part of the procedure takes less than 3 minutes.

Proximal Tibial Cut

The KneeAlign 2 proximal tibial guide is similar in appearance to a standard mechanical tibial cutting guide. It is attached to the proximal tibia with a spring around the calf and 2 pins that hold the device aligned with the medial third of the tibial tubercle. A stylus is then centered on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) footprint, which sets the proximal mechanical axis point of the tibia (Figure 2). An offset number is read off the stylus on the ACL footprint, and this number is matched on the ankle offset portion of the guide. The device has 2 sensors. One sensor is on the chassis of the device, and the other is on a mobile arm. Movements between the 2 are monitored by the accelerometers, allowing for accurate maintenance of alignment position even with motion in the leg. A point is taken from the lateral malleolus and then a second point is taken from the medial malleolus. These points are used to determine the center of the ankle joint, which sets the distal mechanical axis point. Once mechanical axis of the tibia is determined, the tibial cutting guide is pinned in place, and can be adjusted with real-time guidance of the varus/valgus and posterior slope values seen on the device (Figure 3). Cut depth is once again determined with a mechanical stylus.

Limitations

Although these devices have proven to be very accurate, surgeons must continue to recognize that all tools can have errors. With computerized guides of any sort, these errors are usually user errors that cannot be detected by the device. Surgeons need to be able to recognize this and always double-check bone cuts for accuracy. Templating the bone cuts prior to surgery is an effective double-check. In addition, many handheld accelerometer devices do not currently assist with the rotational alignment of the femoral component. This is still performed using the surgeon’s preferred technique, and is a limitation of these systems.

Discussion

Currently, TKA provides satisfactory 10-year results with modern implant designs and survival rates as high as 90% to 95%.27,28 Even with good survival rates, a percentage of patients fail within the first 5 years.3 At a single institution, 50% of revision TKAs were related to instability, malalignment, or failure of fixation that occurred less than 2 years after the index procedure.29 In general, TKA with mechanical instrumentation provides satisfactory pain relief and postoperative knee function; however, studies have consistently shown that the use of advanced technology decreases the risk of implant malalignment, which may decrease early implant failure rates as compared to mechanical and some PSI.13,14,22 While there is a paucity of literature that has shown better clinical outcomes with the use of advanced technology, there are studies supporting the notion that proper limb alignment and component positioning improves implant survivorship.23,30

CAS may have additional advantages if the surgeon chooses to place the TKA in an alignment other than a neutral mechanical axis. Kinematic alignment for TKA has gained increasing popularity, where the target of a neutral mechanical axis alignment is not always the goal.31,32 The reported benefit is a more natural ligament tension with the hope of improving patient satisfaction. One concern with this technique is that it is a departure from the long-held teaching that a TKA aligned to a neutral mechanical axis is necessary for long-term implant survivorship.33,34 In addition, if the goal of surgery is to cut the tibia and femur at a specific varus/valgus cut, standard instrumentation may not allow for this level of accuracy. This in turn increases the risk of having a tibial or femoral cut that is outside the commonly accepted standards of alignment, which may lead to early implant failure. If further research suggests alignment is a variable that differs from patient to patient, the use of precise tools to ensure accuracy of executing the preoperatively templated alignment becomes even more important.

As the number of TKAs continues to rise each year, even a small percentage of malaligned knees that go on to revision surgery will create a large burden on the healthcare system.1,3 Although the short-term clinical benefits of CAS have not shown substantial differences as compared to conventional TKA, the number of knees aligned outside of a desired neutral mechanical axis alignment has been shown in multiple studies to be decreased with the use of advanced technology.7,12,34 Although CAS is an additional cost to a primary TKA, if the orthopedic community can decrease the number of TKA revisions due to malalignment from 6.6% to nearly zero, this may decrease the revision burden and overall cost to the healthcare system.1,3

TKA technology continues to evolve, and we must continue to assess each new advance not only to understand how it works, but also to ensure it addresses a specific clinical problem, and to be aware of the costs associated before incorporating it into routine practice. Some argue that the use of advanced technology requires increased surgical time, which in turn ultimately increases costs; however, one study has documented no increase in surgical time with handheld navigation while maintaining the accuracy of the device.34 In addition, no significant radiographic or clinical differences have been found between handheld navigation and larger console CAS systems, but large console systems have been associated with increased surgical times.22 The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides has proven to provide reliable coronal and sagittal implant alignment that can easily be incorporated into the operating room. More widespread use of such technology will help decrease alignment outliers for TKA, and future long-term clinical outcome studies will be necessary to assess functional outcomes.

Conclusion

Advanced computer based technology offers an additional tool to the surgeon for reliably improving component positioning during TKA. The use of handheld accelerometer- and gyroscope-based guides increases the accuracy of component placement while decreasing the incidence of outliers compared to standard mechanical guides, without the need for a large computer console. Long-term radiographic and patient-reported outcomes are necessary to further validate these devices.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57-63.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28( 8 Suppl):116-119.

4. Sassoon A, Nam D, Nunley R, Barrack R. Systematic review of patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: new but not improved. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):151-158.

5. Anderson KC, Buehler KC, Markel DC. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: comparison with conventional methods. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3):132-138.

6. Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1097-1106.

7. Khakha RS, Chowdhry M, Sivaprakasam M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Radiological and functional outcomes in computer assisted total knee arthroplasty between consultants and trainees - a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(8):1344-1347.

8. Zhu M, Ang CL, Yeo SJ, Lo NN, Chia SL, Chong HC. Minimally invasive computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty compared with conventional total knee arthroplasty: a prospective 9-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Roberts TD, Clatworthy MG, Frampton CM, Young SW. Does computer assisted navigation improve functional outcomes and implant survivability after total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):59-63.

10. de Steiger RN, Liu YL, Graves SE. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(8):635-642.

11. Fehring TK, Mason JB, Moskal J, Pollock DC, Mann J, Williams VJ. When computer-assisted knee replacement is the best alternative. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:132-136.

12. Iorio R, Mazza D, Drogo P, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of an accelerometer-based system for the tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39(3):461-466.

13. Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A. Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:152-159.

14. Ollivier M, Tribot-Laspiere Q, Amzallag J, Boisrenoult P, Pujol N, Beaufils P. Abnormal rate of intraoperative and postoperative implant positioning outliers using “MRI-based patient-specific” compared to “computer assisted” instrumentation in total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

15. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Zhu J, Ruh EL, Howell SM, Barrack RL. Do patient-specific guides improve coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):895-902.

16. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Ruh EL, et al. Are patient-specific cutting blocks cost-effective for total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):889-894.

17. Barrack RL, Ruh EL, Williams BM, Ford AD, Foreman K, Nunley RM. Patient specific cutting blocks are currently of no proven value. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):95-99.

18. Chen JY, Chin PL, Tay DK, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Functional outcome and quality of life after patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(10):1724-1728.

19. Goyal N, Patel AR, Yaffe MA, Luo MY, Stulberg SD. Does implant design influence the accuracy of patient specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1526-1530.

20. Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, et al. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):261-269.

21. Scuderi GR, Fallaha M, Masse V, Lavigne P, Amiot LP, Berthiaume MJ. Total knee arthroplasty with a novel navigation system within the surgical field. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):167-173.

22. Goh GS, Liow MH, Lim WS, Tay DK, Yeo SJ, Tan MH. Accelerometer-based navigation is as accurate as optical computer navigation in restoring the joint line and mechanical axis after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective matched study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1):92-97.

23. Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Liberal indications for minimally invasive oxford unicondylar arthroplasty provide rapid functional recovery and pain relief. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:193-197.

24. Nam D, Jerabek SA, Cross MB, Mayman DJ. Cadaveric analysis of an accelerometer-based portable navigation device for distal femoral cutting block alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Comput Aided Surg. 2012;17(4):205-210.

25. Nam D, Cody EA, Nguyen JT, Figgie MP, Mayman DJ. Extramedullary guides versus portable, accelerometer-based navigation for tibial alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial: winner of the 2013 HAP PAUL award. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):288-294.

26. Bugbee WD, Kermanshahi AY, Munro MM, McCauley JC, Copp SN. Accuracy of a hand-held surgical navigation system for tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(6):1225-1228.

27. Schai PA, Thornhill TS, Scott RD. Total knee arthroplasty with the PFC system. Results at a minimum of ten years and survivorship analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(5):850-858.

28. Pradhan NR, Gambhir A, Porter ML. Survivorship analysis of 3234 primary knee arthroplasties implanted over a 26-year period: a study of eight different implant designs. Knee. 2006;13(1):7-11.

29. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

30. Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):39-43.

31. Cherian JJ, Kapadia BH, Banerjee S, Jauregui JJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Mechanical, anatomical, and kinematic axis in TKA: concepts and practical applications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(2):89-95.

32. Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik K, Ghaly LR, Hull ML. Does varus alignment adversely affect implant survival and function six years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? Int Orthop. 2015;39(11):2117-2124.

33. Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153-156.

34. Huang EH, Copp SN, Bugbee WD. Accuracy of a handheld accelerometer-based navigation system for femoral and tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(11):1906-1910.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57-63.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28( 8 Suppl):116-119.

4. Sassoon A, Nam D, Nunley R, Barrack R. Systematic review of patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: new but not improved. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):151-158.

5. Anderson KC, Buehler KC, Markel DC. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: comparison with conventional methods. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3):132-138.

6. Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1097-1106.

7. Khakha RS, Chowdhry M, Sivaprakasam M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Radiological and functional outcomes in computer assisted total knee arthroplasty between consultants and trainees - a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(8):1344-1347.

8. Zhu M, Ang CL, Yeo SJ, Lo NN, Chia SL, Chong HC. Minimally invasive computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty compared with conventional total knee arthroplasty: a prospective 9-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Roberts TD, Clatworthy MG, Frampton CM, Young SW. Does computer assisted navigation improve functional outcomes and implant survivability after total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):59-63.

10. de Steiger RN, Liu YL, Graves SE. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(8):635-642.

11. Fehring TK, Mason JB, Moskal J, Pollock DC, Mann J, Williams VJ. When computer-assisted knee replacement is the best alternative. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:132-136.

12. Iorio R, Mazza D, Drogo P, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of an accelerometer-based system for the tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2015;39(3):461-466.

13. Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A. Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:152-159.

14. Ollivier M, Tribot-Laspiere Q, Amzallag J, Boisrenoult P, Pujol N, Beaufils P. Abnormal rate of intraoperative and postoperative implant positioning outliers using “MRI-based patient-specific” compared to “computer assisted” instrumentation in total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

15. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Zhu J, Ruh EL, Howell SM, Barrack RL. Do patient-specific guides improve coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):895-902.

16. Nunley RM, Ellison BS, Ruh EL, et al. Are patient-specific cutting blocks cost-effective for total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):889-894.

17. Barrack RL, Ruh EL, Williams BM, Ford AD, Foreman K, Nunley RM. Patient specific cutting blocks are currently of no proven value. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):95-99.

18. Chen JY, Chin PL, Tay DK, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Functional outcome and quality of life after patient-specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(10):1724-1728.

19. Goyal N, Patel AR, Yaffe MA, Luo MY, Stulberg SD. Does implant design influence the accuracy of patient specific instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):1526-1530.

20. Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, et al. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):261-269.

21. Scuderi GR, Fallaha M, Masse V, Lavigne P, Amiot LP, Berthiaume MJ. Total knee arthroplasty with a novel navigation system within the surgical field. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):167-173.

22. Goh GS, Liow MH, Lim WS, Tay DK, Yeo SJ, Tan MH. Accelerometer-based navigation is as accurate as optical computer navigation in restoring the joint line and mechanical axis after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective matched study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1):92-97.

23. Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Liberal indications for minimally invasive oxford unicondylar arthroplasty provide rapid functional recovery and pain relief. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:193-197.

24. Nam D, Jerabek SA, Cross MB, Mayman DJ. Cadaveric analysis of an accelerometer-based portable navigation device for distal femoral cutting block alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Comput Aided Surg. 2012;17(4):205-210.

25. Nam D, Cody EA, Nguyen JT, Figgie MP, Mayman DJ. Extramedullary guides versus portable, accelerometer-based navigation for tibial alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial: winner of the 2013 HAP PAUL award. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):288-294.

26. Bugbee WD, Kermanshahi AY, Munro MM, McCauley JC, Copp SN. Accuracy of a hand-held surgical navigation system for tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(6):1225-1228.

27. Schai PA, Thornhill TS, Scott RD. Total knee arthroplasty with the PFC system. Results at a minimum of ten years and survivorship analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(5):850-858.

28. Pradhan NR, Gambhir A, Porter ML. Survivorship analysis of 3234 primary knee arthroplasties implanted over a 26-year period: a study of eight different implant designs. Knee. 2006;13(1):7-11.

29. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

30. Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):39-43.

31. Cherian JJ, Kapadia BH, Banerjee S, Jauregui JJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Mechanical, anatomical, and kinematic axis in TKA: concepts and practical applications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(2):89-95.

32. Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik K, Ghaly LR, Hull ML. Does varus alignment adversely affect implant survival and function six years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? Int Orthop. 2015;39(11):2117-2124.

33. Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153-156.

34. Huang EH, Copp SN, Bugbee WD. Accuracy of a handheld accelerometer-based navigation system for femoral and tibial resection in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(11):1906-1910.

Computer Navigation and Robotics for Total Knee Arthroplasty

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a good surgical option to relieve pain and improve function in patients with osteoarthritis. The goal of surgery is to achieve a well-aligned prosthesis with well-balanced ligaments in order to minimize wear and improve implant survival. Overall, 82% to 89% of patients are satisfied with their outcomes after TKA, with good 10- to 15-year implant survivorship; however, there is still a subset of patients that are unsatisfied. In many cases, patient dissatisfaction is attributed to improper component alignment.1-3 Over the past decade, computer navigation and robotics have been introduced to control surgical variables so as to gain greater consistency in implant placement and postoperative component alignment.

Computer-assisted navigation tools were introduced not only to improve implant alignment but, more importantly, to optimize clinical outcomes. Most studies have demonstrated that the use of navigation is associated with fewer radiographic outliers after TKA.4 Various studies have compared radiographic results of navigated TKA with results of TKA using standard instrumentation.4-7 While long-term studies are necessary, short-term follow-up has shown that computer-assisted TKA can improve alignment, especially in patients with severe deformity.8-10 Currently, there is no definitive consensus that computer-assisted TKA leads to significantly better component alignment or postoperative outcomes due to the fact that many studies are limited by study design or small cohorts. However, the currently published articles support better component alignment and clinical outcomes with computer-assisted TKA. While some argue that the use of computer-assisted surgery is dependent on the user’s experience, computer-assisted surgery can assist less-experienced surgeons to reliably achieve good midterm outcomes with a low complication rate.8,11 Various studies have looked at computer-assisted TKA at midterm follow-up, with no significant differences in clinical outcome between navigated and traditional techniques. However, long-term studies showing the benefits of computer navigation are beginning to emerge. For example, de Steiger and colleagues12 recently found that computer-assisted TKA reduced the overall revision rate for loosening after TKA in patients less than 65 years of age.

While surgical navigation helps improve implant planning, robotic tools have emerged as a tool to help refine surgical execution. Coupled with surgical navigation tools, robotic control of surgical gestures may further enhance precision in implant placement and/or enable novel implant design features. At present, robotic techniques are increasingly used in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and TKA.13 Studies have demonstrated that the robotic tool is 3 times more accurate with 3 times less variability than conventional techniques in UKA.14 The utility of robotic tools for TKA remains unclear. Robotic-driven automatic cutting guides have been shown to reduce time and improve accuracy compared with navigation guides in femoral TKA cutting procedures in a cadaveric model.15 However, robotic-enabled TKA procedures are poorly described at present, and the clinical implications of their proposed improved precision remain unclear.

Computer navigation and robotic tools in TKA hold the promise of enhanced control of surgical variables that influence clinical outcome. The variables that may be impacted by these advanced tools include implant positioning, lower limb alignment, soft-tissue balance, and, potentially, implant design and fixation. At present, these tools have primarily been shown to improve lower limb alignment in TKA. The clinical impact of the enhanced control of this single surgical variable (lower limb alignment) has been muted in short-term and midterm studies. Future studies should be directed at understanding which surgical variable, or combination of variables, it is most essential to precisely control so as to positively impact clinical outcomes. ◾

1. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57-63.

2. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(404):7-13.

3. Emmerson KP, Morgan CG, Pinder IM. Survivorship analysis of the Kinematic Stabilizer total knee replacement: a 10- to 14-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(3):441-445.

4. Liow MH, Xia Z, Wong MK, Tay KJ, Yeo SJ, Chin PL. Robot-assisted total knee arthroplasty accurately restores the joint line and mechanical axis. A prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(12):2373-2377.

5. Sparmann M, Wolke B, Czupalla H, Banzer D, Zink A. Positioning of total knee arthroplasty with and without navigation support. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(6):830-835.

6. Hoffart HE, Langenstein E, Vasak N. A prospective study comparing the functional outcome of computer-assisted and conventional total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(2):194-199.

7. Cip J, Widemschek M, Luegmair M, Sheinkop MB, Benesch T, Martin A. Conventional versus computer-assisted technique for total knee arthroplasty: a minimum of 5-year follow-up of 200 patients in a prospective randomized comparative trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1795-1802.

8. Huang TW, Peng KT, Huang KC, Lee MS, Hsu RW. Differences in component and limb alignment between computer-assisted and conventional surgery total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(12):2954-2961.

9. Lee CY, Lin SJ, Kuo LT, et al. The benefits of computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty on coronal alignment with marked femoral bowing in Asian patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:122.

10. Hernandez-Vaquero D, Noriega-Fernandez A, Fernandez-Carreira JM, Fernandez-Simon JM, Llorens de los Rios J. Computer-assisted surgery improves rotational positioning of the femoral component but not the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(12):3127-3134.

11. Khakha RS, Chowdhry M, Sivaprakasam M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Radiological and functional outcomes in computer assisted total knee arthroplasty between consultants and trainees - a prospective randomized controlled trial [published online ahead of print March 14, 2015]. J Arthroplasty.

12. de Steiger RN, Liu YL, Graves SE. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(8):635-642.

13. Pearle AD, O’Loughlin PF, Kendoff DO. Robot-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(2):230-237.

14. Citak M, Suero EM, Citak M, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: is robotic technology more accurate than conventional technique? Knee. 2013;20(4):268-271.

15. Koulalis D, O’Loughlin PF, Plaskos C, Kendoff D, Cross MB, Pearle AD. Sequential versus automated cutting guides in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2011;18(6):436-442.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a good surgical option to relieve pain and improve function in patients with osteoarthritis. The goal of surgery is to achieve a well-aligned prosthesis with well-balanced ligaments in order to minimize wear and improve implant survival. Overall, 82% to 89% of patients are satisfied with their outcomes after TKA, with good 10- to 15-year implant survivorship; however, there is still a subset of patients that are unsatisfied. In many cases, patient dissatisfaction is attributed to improper component alignment.1-3 Over the past decade, computer navigation and robotics have been introduced to control surgical variables so as to gain greater consistency in implant placement and postoperative component alignment.

Computer-assisted navigation tools were introduced not only to improve implant alignment but, more importantly, to optimize clinical outcomes. Most studies have demonstrated that the use of navigation is associated with fewer radiographic outliers after TKA.4 Various studies have compared radiographic results of navigated TKA with results of TKA using standard instrumentation.4-7 While long-term studies are necessary, short-term follow-up has shown that computer-assisted TKA can improve alignment, especially in patients with severe deformity.8-10 Currently, there is no definitive consensus that computer-assisted TKA leads to significantly better component alignment or postoperative outcomes due to the fact that many studies are limited by study design or small cohorts. However, the currently published articles support better component alignment and clinical outcomes with computer-assisted TKA. While some argue that the use of computer-assisted surgery is dependent on the user’s experience, computer-assisted surgery can assist less-experienced surgeons to reliably achieve good midterm outcomes with a low complication rate.8,11 Various studies have looked at computer-assisted TKA at midterm follow-up, with no significant differences in clinical outcome between navigated and traditional techniques. However, long-term studies showing the benefits of computer navigation are beginning to emerge. For example, de Steiger and colleagues12 recently found that computer-assisted TKA reduced the overall revision rate for loosening after TKA in patients less than 65 years of age.

While surgical navigation helps improve implant planning, robotic tools have emerged as a tool to help refine surgical execution. Coupled with surgical navigation tools, robotic control of surgical gestures may further enhance precision in implant placement and/or enable novel implant design features. At present, robotic techniques are increasingly used in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and TKA.13 Studies have demonstrated that the robotic tool is 3 times more accurate with 3 times less variability than conventional techniques in UKA.14 The utility of robotic tools for TKA remains unclear. Robotic-driven automatic cutting guides have been shown to reduce time and improve accuracy compared with navigation guides in femoral TKA cutting procedures in a cadaveric model.15 However, robotic-enabled TKA procedures are poorly described at present, and the clinical implications of their proposed improved precision remain unclear.