User login

Documentation and billing: Tips for hospitalists

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

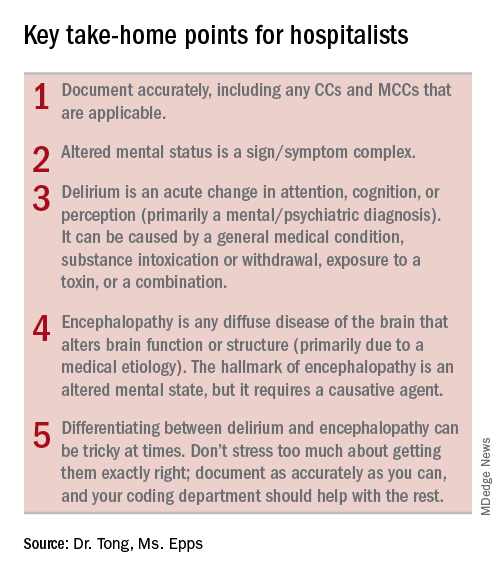

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

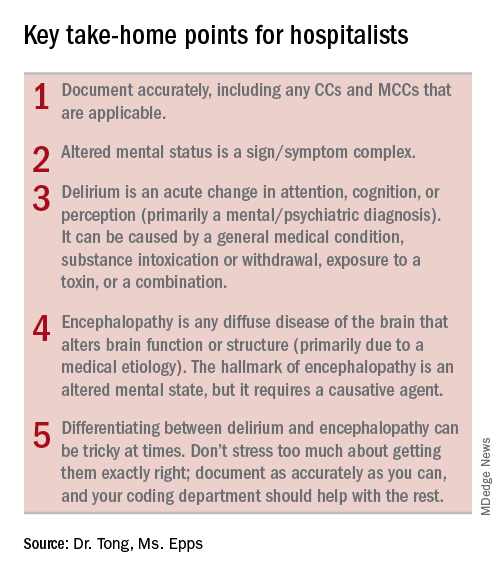

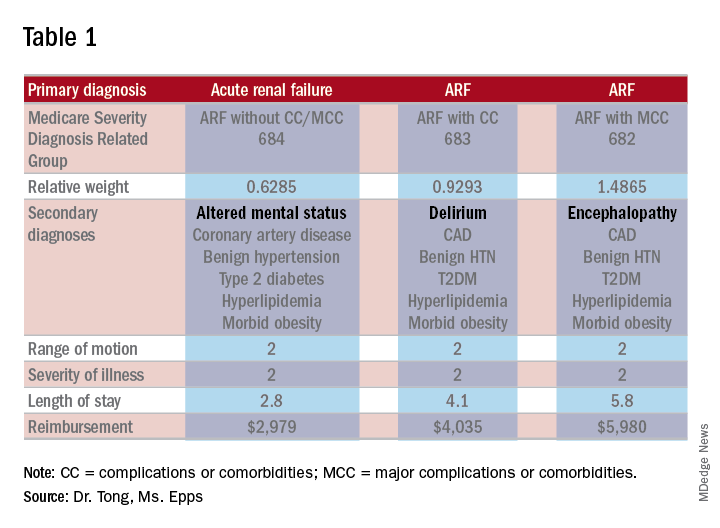

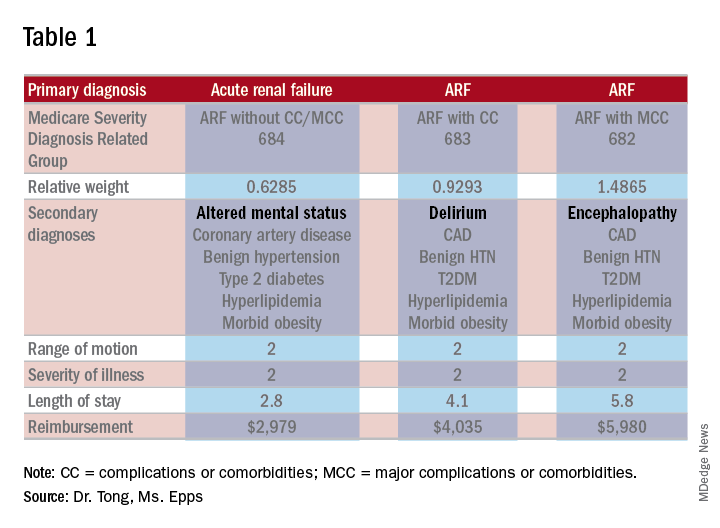

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

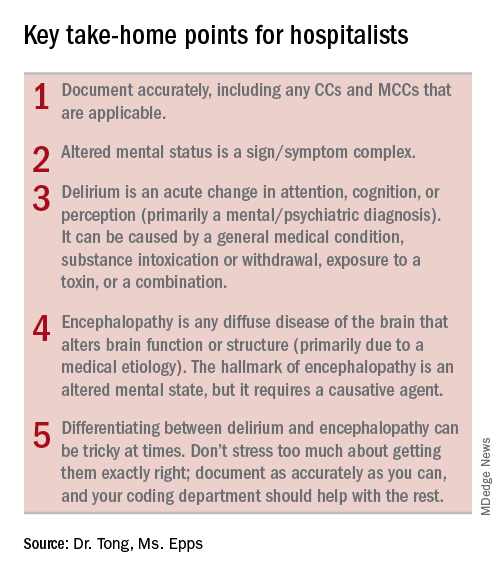

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

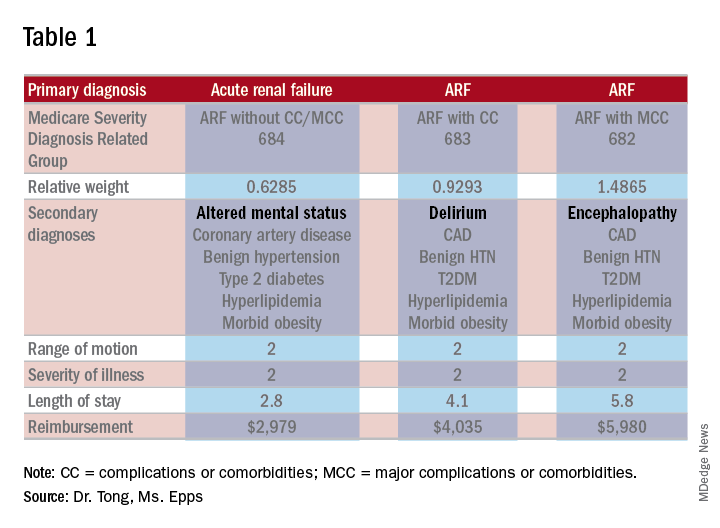

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.