User login

Total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation: Definitive treatment for chronic pancreatitis

For some patients with chronic pancreatitis, the best option is to remove the entire pancreas. This does not necessarily doom the patient to diabetes mellitus, because we can harvest the islet cells and reinsert them so that, lodged in the liver, they can continue making insulin. However, this approach is underemphasized in the general medical literature and is likely underutilized in the United States.

Here, we discuss chronic pancreatitis, the indications for and contraindications to this procedure, its outcomes, and the management of patients who undergo it.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS IS PROGRESSIVE AND PAINFUL

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive condition characterized by chronic inflammation, irreversible fibrosis, and scarring, resulting in loss of both exocrine and endocrine tissue.

According to a National Institutes of Health database, pancreatitis is the seventh most common digestive disease diagnosis on hospitalization, with annual healthcare costs exceeding $3 billion.1 Although data are scarce, by some estimates the incidence of chronic pancreatitis ranges from 4 to 14 per 100,000 person-years, and the prevalence ranges from 26.4 to 52 per 100,000.2–4 Moreover, a meta-analysis5 found that acute pancreatitis progresses to chronic pancreatitis in 10% of patients who have a first episode of acute pancreatitis and in 36% who have recurrent episodes.

Historically, alcoholism was and still is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis, contributing to 60% to 90% of cases in Western countries.6,7 However, cases due to nonalcoholic causes have been increasing, and in more than one-fourth of patients, no identifiable cause is found.6,8 Smoking is an independent risk factor.6,8,9 Some cases can be linked to genetic abnormalities, particularly in children.10

The clinical manifestations of chronic pancreatitis include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (leading to malnutrition and steatorrhea), endocrine insufficiency (causing diabetes mellitus), and intractable pain.11 Pain is the predominant clinical symptom early in the disease and is often debilitating and difficult to manage. Uncontrolled pain has a devastating impact on quality of life and may become complicated by narcotic dependence.

The pain of chronic pancreatitis is often multifactorial, with mechanisms that include increased intraductal pressure from obstruction of the pancreatic duct, pancreatic ischemia, neuronal injury, and neuroimmune interactions between neuronal processes and chronic inflammation.12

Treatment: Medical and surgical

In chronic pancreatitis, the aim of treatment is to alleviate deficiencies of exocrine and endocrine function and mitigate the pain. Patients who smoke or drink alcohol should be strongly encouraged to quit.

Loss of exocrine function is mainly managed with oral pancreatic enzyme supplements, and diabetes control is often attained with insulin therapy.13 Besides helping digestion, pancreatic enzyme therapy in the form of nonenteric tablets may also reduce pain and pancreatitis attacks.14 The mechanism may be by degrading cholecystokinin-releasing factor in the duodenum, lowering cholecystokinin levels and thereby reducing pain.12

Nonnarcotic analgesics are often the first line of therapy for pain management, but many patients need narcotic analgesics. Along with narcotics, adjunctive agents such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and gabapentinoids have been used to treat chronic pancreatitis pain, but with limited success.15

In patients for whom medical pain management has failed, one can consider another option, such as nerve block, neurolysis, or endoscopic or surgical therapy. Neuromodulators are often prescribed by pain clinics.15 Percutaneous and endoscopic celiac ganglion blocks can be an option but rarely achieve substantial or permanent pain relief, and the induced transient responses (on average 2 to 4 months) often cannot be repeated.14–17

Surgical options to relieve pain try to preserve pancreatic function and vary depending on the degree of severity and nature of pancreatic damage. In broad terms, the surgical procedures can be divided into two types:

- Drainage procedures (eg, pseudocyst drainage; minimally invasive endoscopic duct drainage via sphincterotomy or stent placement, or both; pancreaticojejunostomy)

- Resectional procedures (eg, distal pancreatectomy, isolated head resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy, Whipple procedure, total pancreatectomy).

In carefully selected patients, total pancreatectomy can be offered to remove the cause of the pain.18 This procedure is most often performed in patients who have small-duct disease or a genetic cause or for whom other surgical procedures have failed.11

HISTORY OF THE PROCEDURE

Islet cell transplantation grew out of visionary work by Paul Lacy and David Scharp at the University of Washington at Seattle, whose research focused on isolating and transplanting islet cells in rodent models. The topic has been reviewed by Jahansouz et al.19 In the 1970s, experiments in pancreatectomized dogs showed that transplanting unpurified pancreatic islet tissue that was dispersed by collagenase digestion into the spleen or portal vein could prevent diabetes.20,21 In 1974, the first human trials of transplanting islet cells were conducted, using isolated islets from cadaveric donors to treat diabetes.19

In the past, pancreatectomy was performed to treat painful chronic pancreatitis, but it was viewed as undesirable because removing the gland would inevitably cause insulin-dependent diabetes.22 That changed in 1977 at the University of Minnesota, with the first reported islet cell autotransplant after pancreatectomy. The patient remained pain-free and insulin-independent long-term.23 This seminal case showed that endocrine function could be preserved by autotransplant of islets prepared from the excised pancreas.24

In 1992, Pyzdrowski et al25 reported that intrahepatic transplant of as few as 265,000 islets was enough to prevent the need for insulin therapy. Since this technique was first described, there have been many advances, and now more than 30 centers worldwide do it.

PRIMARY INDICATION: INTRACTABLE PAIN

Interest has been growing in using total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant to treat recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and hereditary pancreatitis. The rationale is that removing the offending tissue eliminates pancreatitis, pain, and cancer risk, while preserving and replacing the islet cells prevents the development of brittle diabetes with loss of insulin and glucagon.26

Proposed criteria for total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant

Bellin et al14 proposed five criteria for patient selection for this procedure based on imaging studies, pancreatic function tests, and histopathology to detect pancreatic fibrosis. Patients must fulfill all five of the following criteria:

Criterion 1. Diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, based on chronic abdominal pain lasting more than 6 months with either at least one of the following:

- Pancreatic calcifications on computed tomography

- At least two of the following: four or more of nine criteria on endoscopic ultrasonography described by Catalano et al,27 a compatible ductal or parenchymal abnormality on secretin magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; abnormal endoscopic pancreatic function test (peak HCO2 ≤ 80 mmol/L)

- Histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis

- Compatible clinical history and documented hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 gene mutation)

OR

- History of recurrent acute pancreatitis (more than one episode of characteristic pain associated with imaging diagnostic of acute pancreatitis or elevated serum amylase or lipase > 3 times the upper limit of normal).

Criterion 2. At least one of the following:

- Daily narcotic dependence

- Pain resulting in impaired quality of life, which may include inability to attend school, recurrent hospitalizations, or inability to participate in usual age-appropriate activities.

Criterion 3. Complete evaluation with no reversible cause of pancreatitis present or untreated.

Criterion 4. Failure to respond to maximal medical and endoscopic therapy.

Criterion 5. Adequate islet cell function (nondiabetic or C-peptide-positive). Patients with C-peptide-negative diabetes meeting criteria 1 to 4 are candidates for total pancreatectomy alone.

The primary goal is to treat intractable pain and improve quality of life in selected patients with chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis when endoscopic and prior surgical therapies have failed, and whose impairment due to pain is substantial enough to accept the risk of postoperative insulin-dependent diabetes and lifelong commitment to pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.15,26 Patients with a known genetic cause of chronic pancreatitis should be offered special consideration for the procedure, as their disease is unlikely to remit.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant should not be performed in patients with active alcoholism, illicit drug use, or untreated or poorly controlled psychiatric illnesses that could impair the patient’s ability to adhere to a complicated postoperative medical regimen.

A poor support network may be a relative contraindication in view of the cost and complexity of diabetic and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.18,26

Islet cell autotransplant is contraindicated in patients with conditions such as C-peptide-negative or type 1 diabetes or a history of portal vein thrombosis, portal hypertension, significant liver disease, high-risk cardiopulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer (Table 1).26

WHEN TO CONSIDER REFERRAL FOR THIS PROCEDURE

The choice of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant vs conventional surgery must be individualized on the basis of each patient’s anatomy, comorbidities, symptom burden, presence or degree of diabetes, and rate of disease progression. The most important factors to consider in determining the need for and timing of this procedure are the patient’s pain, narcotic requirements, and impaired ability to function.26

Sooner rather than later?

An argument can be made for performing this procedure sooner in the course of the disease rather than later when all else has failed. First, prolonged pain can result in central sensitization, in which the threshold for perceiving pain is lowered by damage to the nociceptive neurons from repeated stimulation and inflammation.28

Further, prolonged opioid therapy can lead to opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which may also render patients more sensitive to pain and aggravate their preexisting pain.26,28

In addition, although operative drainage procedures and partial resections are often considered the gold standard for chronic pancreatitis management, patients who undergo partial pancreatectomy or lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure) have fewer islet cells left to harvest (about 50% fewer) if they subsequently undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.22,26

Therefore, performing this procedure earlier may help the patient avoid chronic pain syndromes and complications of chronic opioid use, including hyperalgesia, and give the best chance of harvesting enough islet cells to prevent or minimize diabetes afterward.11

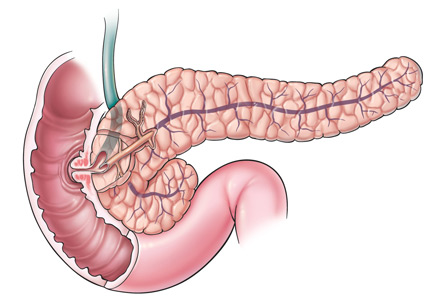

REMOVING THE PANCREAS, RETURNING THE ISLET CELLS

During this procedure, the blood supply to the pancreas must be preserved until just before its removal to minimize warm ischemia of the islet cells.18,29 Although there are several surgical variations, a pylorus-preserving total pancreatectomy with duodenectomy is typically performed, usually with splenectomy to preserve perfusion to the body and tail.30

The resected pancreas is taken to the islet isolation laboratory. There, the pancreatic duct is cannulated to fill the organ with a cold collagenase solution, followed by gentle mechanical dispersion using the semiautomated Ricordi method,31 which separates the islet cells from the exocrine tissue.32

The number of islet cells is quantified as islet equivalents; 1 islet equivalent is equal to the volume of an islet with a diameter of 150 µm. Islet equivalents per kilogram of body weight is the unit commonly used to report the graft amount transplanted.33

After digestion, the islet cells can be purified or partially purified by a gradient separation method using a Cobe 2991 cell processor (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan),34 or can be transplanted as an unpurified preparation. In islet cell autotransplant for chronic pancreatitis, purification is not always necessary due to the small tissue volume extracted from the often atrophic and fibrotic pancreas.32 The decision to purify depends on the postdigest tissue volume; usually, a tissue volume greater than 0.25 mL/kg body weight is an indication to at least partially purify.18,35

The final preparation is returned to the operating room, and after heparin is given, the islets are infused into the portal system using a stump of the splenic vein, or alternatively through direct puncture of the portal vein or cannulation of the umbilical vein.32,36 If the portal vein pressure reaches 25 cm H2O, the infusion is stopped and the remaining islets can be placed in the peritoneal cavity or elsewhere.18 Transplant of the islets into the liver or peritoneum allows the islets to secrete insulin into the hepatic portal circulation, which is the route used by the native pancreas.22

CONTROLLING GLUCOSE DURING AND AFTER THE PROCEDURE

Animal studies have shown that hyperglycemia impairs islet revascularization,37 and glucose toxicity may cause dysfunction and structural lesions of the transplanted islets.11,38

Therefore, during and after the procedure, most centers maintain euglycemia by an intravenous insulin infusion and subsequently move to subcutaneous insulin when the patient starts eating again. Some centers continue insulin at discharge and gradually taper it over months, even in patients who can possibly achieve euglycemia without it.

OUTCOMES

Many institutions have reported their clinical outcomes in terms of pain relief, islet function, glycemic control, and improvement of quality of life. The largest series have been from the University of Minnesota, Leicester General Hospital, the University of Cincinnati, and the Medical University of South Carolina.

Insulin independence is common but wanes with time

The ability to achieve insulin independence after islet autotransplant appears to be related to the number of islets transplanted, with the best results when more than 2,000 or 3,000 islet equivalents/kg are transplanted.39,40

Sutherland et al18 reported that of 409 patients who underwent islet cell autotransplant at the University of Minnesota (the largest series reported to date), 30% were insulin-independent at 3 years, 33% had partial graft function (defined by positive C-peptide), and 82% achieved a mean hemoglobin A1c of less than 7%. However, in the subset who received more than 5,000 islet equivalents/kg, nearly three-fourths of patients were insulin-independent at 3 years.

The Leicester General Hospital group presented long-term data on 46 patients who underwent total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant. Twelve of the 46 had shown periods of insulin independence for a median of 16.5 months, and 5 remained insulin-free at the time of the publication.41 Over the 10 years of follow-up, insulin requirements and hemoglobin A1c increased notably. However, all of the patients tested C-peptide-positive, suggesting long-lasting graft function.

Most recently, the University of Cincinnati group reported long-term data on 116 patients. The insulin independence rate was 38% at 1 year, decreasing to 27% at 5 years. The number of patients with partial graft function was 38% at 1 year and 35% at 5 years.42

Thus, all three institutions confirmed that the autotransplanted islets continue to secrete insulin long-term, but that function decreases over time.

Pancreatectomy reduces pain

Multiple studies have shown that total pancreatectomy reduces pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ahmad et al43 reported a marked reduction in narcotic use (mean morphine equivalents 206 mg/day before surgery, compared with 90 mg after), and a 58% reduction in pain as demonstrated by narcotic independence.

In the University of Minnesota series, 85% of the 409 patients had less pain at 2 years, and 59% were able to stop taking narcotics.18

The University of Cincinnati group reported a narcotic independence rate of 55% at 1 year, which continued to improve to 73% at 5 years.42

Although the source of pain is removed, pain persists or recurs in 10% to 20% of patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, showing that the pathogenesis of pain is complex, and some uncertainty exists about it.26

Quality of life

Reports evaluating health-related quality of life after total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant are limited.

The University of Cincinnati group reported the long-term outcomes of quality of life as measured by the Short Form 36 Health Survey.42 Ninety-two percent of patients reported overall improvement in their health at 1 year, and 85% continued to report improved health more than 5 years after the surgery.

In a series of 20 patients, 79% to 90% reported improvements in the seven various domains of the Pain Disability Index. In addition, 60% showed improvement in depression and 70% showed improvement in anxiety. The greatest improvements were in those who had not undergone prior pancreatic surgery, who were younger, and in those with higher levels of preoperative pain.30

Similarly, in a series of 74 patients, the Medical University of South Carolina group reported significant improvement in physical and mental health components of the Short Form 12 Health Survey and an associated decrease in daily narcotic requirements. Moreover, the need to start or increase the dose of insulin after the surgery was not associated with a lower quality of life.44

OFF-SITE ISLET CELL ISOLATION

Despite the positive outcomes in terms of pain relief and insulin independence in many patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, few medical centers have an on-site islet-processing facility. Since the mid-1990s, a few centers have been able to circumvent this limitation by working with off-site islet cell isolation laboratories.45,46

The University of California, Los Angeles, first reported on a series of nine patients who received autologous islet cells after near-total or total pancreatectomy using a remote islet cell isolation facility, with results comparable to those of other large institutions.45

Similarly, the procedure has been performed at Cleveland Clinic since 2007 with the collaboration of an off-site islet cell isolation laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. A cohort study from this collaboration published in 2015 showed that in 36 patients (mean follow-up 28 months, range 3–26 months), 33% were insulin-independent, with a C-peptide-positive rate of 70%. This is the largest cohort to date from a center utilizing an off-site islet isolation facility.47

In view of the positive outcomes at these centers, lack of a local islet-processing facility should no longer be a barrier to total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

PATIENT CARE AFTER THE PROCEDURE

A multidisciplinary team is an essential component of the postoperative management of patients who undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

For patients who had been receiving narcotics for a long time before surgery or who were receiving frequent doses, an experienced pain management physician should be involved in the patient’s postoperative care.

Because islet function can wane over time, testing for diabetes should be done at least annually for the rest of the patient’s life and should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and C-peptide, along with self-monitored blood glucose.26

All patients who have surgically induced exocrine insufficiency are at risk of malabsorption and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.48 Hence, lifelong pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is mandatory. Nutritional monitoring should include assessment of steatorrhea, body composition, and fat-soluble vitamin levels (vitamins A, D, and E) at least every year.26 Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk for low bone density from malabsorption of vitamin D and calcium; therefore, it is recommended that a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone density scan be obtained.26,49

Patients who undergo splenectomy as part of their procedure will require appropriate precautions and ongoing vaccinations as recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.26,50,51

WHAT TO EXPECT FOR THE FUTURE

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases has reviewed the potential future research directions for total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant.15

Patient selection remains challenging despite the availability of criteria15 and guidelines.26 More research is needed to better assess preoperative beta-cell function and to predict postoperative outcomes. Mixed meal-tolerance testing is adopted by most clinical centers to predict posttransplant beta-cell function. The use of arginine instead of glucagon in a stimulation test for insulin and C-peptide response has been validated and may allow more accurate assessment.52,53

Another targeted area of research is the advancement of safety and metabolic outcomes. Techniques to minimize warm ischemic time and complications are being evaluated. Islet isolation methods that yield more islets, reduce beta-cell apoptosis, and can isolate islets from glands with malignancy should be further investigated.54 Further, enhanced islet infusion methods that achieve lower portal venous pressures and minimize portal vein thrombosis are needed.

Unfortunately, the function of transplanted islet grafts declines over time. This phenomenon is at least partially attributed to the immediate blood-mediated inflammatory response,55,56 along with islet hypoxia,57 leading to islet apoptosis. Research on different strategies is expanding our knowledge in islet engraftment and posttransplant beta-cell apoptosis, with the expectation that the transplanted islet lifespan will increase. Alternative transplant sites with low inflammatory reaction, such as the omental pouch,58 muscle,59 and bone marrow,60 have shown encouraging data. Other approaches, such as adjuvant anti-inflammatory agents and heparinization, have been proposed.15

Research into complications is also of clinical importance. There is growing attention to hypoglycemia unrelated to exogenous insulin use in posttransplant patients. One hypothesis is that glucagon secretion, a counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia, is defective if the islet cells are transplanted into the liver, and that implanting them into another site may avoid this effect.61

- Everhart JE. Pancreatitis. In: Everhart JE, editor. The Burden of Digestive Diseases in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of

- Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2008. www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/Pages/burden-digestive-diseases-in-united-states-report.aspx. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, Dierkhising RA, Chari ST. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:2192–2199.

- Lévy P, Barthet M, Mollard BR, Amouretti M, Marion-Audibert AM, Dyard F. Estimation of the prevalence and incidence of chronic pancreatitis and its complications. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006; 30:838–844.

- Hirota M, Shimosegawa T, Masamune A, et al; Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases. The seventh nationwide epidemiological survey for chronic pancreatitis in Japan: clinical significance of smoking habit in Japanese patients. Pancreatology 2014; 14:490–496.

- Sankaran SJ, Xiao AY, Wu LM, Windsor JA, Forsmark CE, Petrov MS. Frequency of progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis and risk factors: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:1490–1500.e1.

- Coté GA, Yadav D, Slivka A, et al; North American Pancreatitis Study Group. Alcohol and smoking as risk factors in an epidemiology study of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:266–273.

- Muniraj T, Aslanian HR, Farrell J, Jamidar PA. Chronic pancreatitis, a comprehensive review and update. Part I: epidemiology, etiology, risk factors, genetics, pathophysiology, and clinical features. Dis Mon 2014; 60:530–550.

- Frulloni L, Gabbrielli A, Pezzilli R, et al; PanCroInfAISP Study Group. Chronic pancreatitis: report from a multicenter Italian survey (PanCroInfAISP) on 893 patients. Dig Liver Dis 2009; 41:311–317.

- Talamini G, Bassi C, Falconi M, et al. Alcohol and smoking as risk factors in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis Sci 1999; 44:1303–1311.

- Schwarzenberg SJ, Bellin M, Husain SZ, et al. Pediatric chronic pancreatitis is associated with genetic risk factors and substantial disease burden. J Pediatr 2015; 166:890–896.e1.

- Blondet JJ, Carlson AM, Kobayashi T, et al. The role of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am 2007; 87:1477–1501.

- Lieb JG 2nd, Forsmark CE. Review article: pain and chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29:706–719.

- Lin YK, Johnston PC, Arce K, Hatipoglu BA. Chronic pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2015; 13:319–331.

- Bellin MD, Gelrud A, Arreaza-Rubin G, et al. Total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation: summary of a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases workshop. Pancreas 2014; 43:1163–1171.

- Muniraj T, Aslanian HR, Farrell J, Jamidar PA. Chronic pancreatitis, a comprehensive review and update. Part II: diagnosis, complications, and management. Dis Mon 2015; 61:5–37.

- Warshaw AL, Banks PA, Fernández-Del Castillo C. AGA technical review: treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1998; 115:765–776.

- Chauhan S, Forsmark CE. Pain management in chronic pancreatitis: a treatment algorithm. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 24:323–335.

- Sutherland DE, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 2012; 214:409–426.

- Jahansouz C, Jahansouz C, Kumer SC, Brayman KL. Evolution of beta-cell replacement therapy in diabetes mellitus: islet cell transplantation. J Transplant 2011; 2011:247959.

- Kretschmer GJ, Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Cain TL, Najarian JS. Autotransplantation of pancreatic islets without separation of exocrine and endocrine tissue in totally pancreatectomized dogs. Surgery 1977; 82:74–81.

- Kretschmer GJ, Sutherland DR, Matas AJ, Payne WD, Najarian JS. Autotransplantation of pancreatic fragments to the portal vein and spleen of totally pancreatectomized dogs: a comparative evaluation. Ann Surg 1978; 187:79–86.

- Bellin MD, Sutherland DE, Robertson RP. Pancreatectomy and autologous islet transplantation for painful chronic pancreatitis: indications and outcomes. Hosp Pract (1995) 2012; 40:80–87.

- Najarian JS, Sutherland DE, Baumgartner D, et al. Total or near total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 1980; 192:526–542.

- Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Najarian JS. Pancreatic islet cell transplantation. Surg Clin North Am 1978; 58:365–382.

- Pyzdrowski KL, Kendall DM, Halter JB, Nakhleh RE, Sutherland DE, Robertson RP. Preserved insulin secretion and insulin independence in recipients of islet autografts. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:220–226.

- Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Gelrud A, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in chronic pancreatitis: recommendations from PancreasFest. Pancreatology 2014; 14:27–35.

- Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, et al. EUS-based criteria for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69:1251–1261.

- Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 2006; 104:570–587.

- Bramis K, Gordon-Weeks AN, Friend PJ, et al. Systematic review of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2012; 99:761–766.

- Walsh RM, Saavedra JR, Lentz G, et al. Improved quality of life following total pancreatectomy and auto-islet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16:1469–1477.

- Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Scharp DW. Automated islet isolation from human pancreas. Diabetes 1989; 38(suppl 1):140–142.

- Witkowski P, Savari O, Matthews JB. Islet autotransplantation and total pancreatectomy. Adv Surg 2014; 48:223–233.

- Bellin MD, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, et al. Islet autotransplantation to preserve beta cell mass in selected patients with chronic pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus undergoing total pancreatectomy. Pancreas 2013; 42:317–321.

- Anazawa T, Matsumoto S, Yonekawa Y, et al. Prediction of pancreatic tissue densities by an analytical test gradient system before purification maximizes human islet recovery for islet autotransplantation/allotransplantation. Transplantation 2011; 91:508–514.

- Lake SP, Bassett PD, Larkins A, et al. Large-scale purification of human islets utilizing discontinuous albumin gradient on IBM 2991 cell separator. Diabetes 1989; 38(suppl 1):143–145.

- Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Schwarzenberg SJ, et al. Quality of life improves for pediatric patients after total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant for chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:793–799.

- Andersson A, Korsgren O, Jansson L. Intraportally transplanted pancreatic islets revascularized from hepatic arterial system. Diabetes 1989; 38(suppl 1):192–195.

- Leahy JL, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Beta-cell dysfunction induced by chronic hyperglycemia. Current ideas on mechanism of impaired glucose-induced insulin secretion. Diabetes Care 1992; 15:442–455.

- Bellin MD, Carlson AM, Kobayashi T, et al. Outcome after pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008; 47:37–44.

- White SA, Davies JE, Pollard C, et al. Pancreas resection and islet autotransplantation for end-stage chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2001; 233:423–431.

- Webb MA, Illouz SC, Pollard CA, et al. Islet auto transplantation following total pancreatectomy: a long-term assessment of graft function. Pancreas 2008; 37:282–287.

- Wilson GC, Sutton JM, Abbott DE, et al. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation: is it a durable operation? Ann Surg 2014; 260:659–667.

- Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, et al. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201:680–687.

- Dorlon M, Owczarski S, Wang H, Adams D, Morgan K. Increase in postoperative insulin requirements does not lead to decreased quality of life after total pancreatectomy with islet cell autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Am Surg 2013; 79:676–680.

- Tai DS, Shen N, Szot GL, et al. Autologous islet transplantation with remote islet isolation after pancreas resection for chronic pancreatitis. JAMA Surg 2015; 150:118–124.

- Rabkin JM, Olyaei AJ, Orloff SL, et al. Distant processing of pancreas islets for autotransplantation following total pancreatectomy. Am J Surg 1999; 177:423–427.

- Johnston PC, Lin YK, Walsh RM, et al. Factors associated with islet yield and insulin independence after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation in patients with chronic pancreatitis utilizing off-site islet isolation: Cleveland Clinic experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:1765–1770.

- Dresler CM, Fortner JG, McDermott K, Bajorunas DR. Metabolic consequences of (regional) total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg 1991; 214:131–140.

- Duggan SN, O’Sullivan M, Hamilton S, Feehan SM, Ridgway PF, Conlon KC. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk for osteoporosis. Pancreas 2012; 41:1119–1124.

- Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:e44–e100.

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet 2011; 378:86–97.

- Robertson RP, Raymond RH, Lee DS, et al; Beta Cell Project Team of the Foundation for the NIH Biomarkers Consortium. Arginine is preferred to glucagon for stimulation testing of beta-cell function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014; 307:E720–E727.

- Robertson RP, Bogachus LD, Oseid E, et al. Assessment of beta-cell mass and alpha- and beta-cell survival and function by arginine stimulation in human autologous islet recipients. Diabetes 2015; 64:565–572.

- Balzano G, Piemonti L. Autologous islet transplantation in patients requiring pancreatectomy for neoplasm. Curr Diab Rep 2014; 14:512.

- Naziruddin B, Iwahashi S, Kanak MA, Takita M, Itoh T, Levy MF. Evidence for instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction in clinical autologous islet transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014; 14:428–437.

- Abdelli S, Ansite J, Roduit R, et al. Intracellular stress signaling pathways activated during human islet preparation and following acute cytokine exposure. Diabetes 2004; 53:2815–2823.

- Olsson R, Olerud J, Pettersson U, Carlsson PO. Increased numbers of low-oxygenated pancreatic islets after intraportal islet transplantation. Diabetes 2011; 60:2350–2353.

- Berman DM, O’Neil JJ, Coffey LC, et al. Long-term survival of nonhuman primate islets implanted in an omental pouch on a biodegradable scaffold. Am J Transplant 2009; 9:91–104.

- Sterkers A, Hubert T, Gmyr V, et al. Islet survival and function following intramuscular autotransplantation in the minipig. Am J Transplant 2013; 13:891–898.

- Maffi P, Balzano G, Ponzoni M, et al. Autologous pancreatic islet transplantation in human bone marrow. Diabetes 2013; 62:3523–3531.

- Bellin MD, Parazzoli S, Oseid E, et al. Defective glucagon secretion during hypoglycemia after intrahepatic but not nonhepatic islet autotransplantation. Am J Transplant 2014; 14:1880–1886.

For some patients with chronic pancreatitis, the best option is to remove the entire pancreas. This does not necessarily doom the patient to diabetes mellitus, because we can harvest the islet cells and reinsert them so that, lodged in the liver, they can continue making insulin. However, this approach is underemphasized in the general medical literature and is likely underutilized in the United States.

Here, we discuss chronic pancreatitis, the indications for and contraindications to this procedure, its outcomes, and the management of patients who undergo it.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS IS PROGRESSIVE AND PAINFUL

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive condition characterized by chronic inflammation, irreversible fibrosis, and scarring, resulting in loss of both exocrine and endocrine tissue.

According to a National Institutes of Health database, pancreatitis is the seventh most common digestive disease diagnosis on hospitalization, with annual healthcare costs exceeding $3 billion.1 Although data are scarce, by some estimates the incidence of chronic pancreatitis ranges from 4 to 14 per 100,000 person-years, and the prevalence ranges from 26.4 to 52 per 100,000.2–4 Moreover, a meta-analysis5 found that acute pancreatitis progresses to chronic pancreatitis in 10% of patients who have a first episode of acute pancreatitis and in 36% who have recurrent episodes.

Historically, alcoholism was and still is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis, contributing to 60% to 90% of cases in Western countries.6,7 However, cases due to nonalcoholic causes have been increasing, and in more than one-fourth of patients, no identifiable cause is found.6,8 Smoking is an independent risk factor.6,8,9 Some cases can be linked to genetic abnormalities, particularly in children.10

The clinical manifestations of chronic pancreatitis include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (leading to malnutrition and steatorrhea), endocrine insufficiency (causing diabetes mellitus), and intractable pain.11 Pain is the predominant clinical symptom early in the disease and is often debilitating and difficult to manage. Uncontrolled pain has a devastating impact on quality of life and may become complicated by narcotic dependence.

The pain of chronic pancreatitis is often multifactorial, with mechanisms that include increased intraductal pressure from obstruction of the pancreatic duct, pancreatic ischemia, neuronal injury, and neuroimmune interactions between neuronal processes and chronic inflammation.12

Treatment: Medical and surgical

In chronic pancreatitis, the aim of treatment is to alleviate deficiencies of exocrine and endocrine function and mitigate the pain. Patients who smoke or drink alcohol should be strongly encouraged to quit.

Loss of exocrine function is mainly managed with oral pancreatic enzyme supplements, and diabetes control is often attained with insulin therapy.13 Besides helping digestion, pancreatic enzyme therapy in the form of nonenteric tablets may also reduce pain and pancreatitis attacks.14 The mechanism may be by degrading cholecystokinin-releasing factor in the duodenum, lowering cholecystokinin levels and thereby reducing pain.12

Nonnarcotic analgesics are often the first line of therapy for pain management, but many patients need narcotic analgesics. Along with narcotics, adjunctive agents such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and gabapentinoids have been used to treat chronic pancreatitis pain, but with limited success.15

In patients for whom medical pain management has failed, one can consider another option, such as nerve block, neurolysis, or endoscopic or surgical therapy. Neuromodulators are often prescribed by pain clinics.15 Percutaneous and endoscopic celiac ganglion blocks can be an option but rarely achieve substantial or permanent pain relief, and the induced transient responses (on average 2 to 4 months) often cannot be repeated.14–17

Surgical options to relieve pain try to preserve pancreatic function and vary depending on the degree of severity and nature of pancreatic damage. In broad terms, the surgical procedures can be divided into two types:

- Drainage procedures (eg, pseudocyst drainage; minimally invasive endoscopic duct drainage via sphincterotomy or stent placement, or both; pancreaticojejunostomy)

- Resectional procedures (eg, distal pancreatectomy, isolated head resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy, Whipple procedure, total pancreatectomy).

In carefully selected patients, total pancreatectomy can be offered to remove the cause of the pain.18 This procedure is most often performed in patients who have small-duct disease or a genetic cause or for whom other surgical procedures have failed.11

HISTORY OF THE PROCEDURE

Islet cell transplantation grew out of visionary work by Paul Lacy and David Scharp at the University of Washington at Seattle, whose research focused on isolating and transplanting islet cells in rodent models. The topic has been reviewed by Jahansouz et al.19 In the 1970s, experiments in pancreatectomized dogs showed that transplanting unpurified pancreatic islet tissue that was dispersed by collagenase digestion into the spleen or portal vein could prevent diabetes.20,21 In 1974, the first human trials of transplanting islet cells were conducted, using isolated islets from cadaveric donors to treat diabetes.19

In the past, pancreatectomy was performed to treat painful chronic pancreatitis, but it was viewed as undesirable because removing the gland would inevitably cause insulin-dependent diabetes.22 That changed in 1977 at the University of Minnesota, with the first reported islet cell autotransplant after pancreatectomy. The patient remained pain-free and insulin-independent long-term.23 This seminal case showed that endocrine function could be preserved by autotransplant of islets prepared from the excised pancreas.24

In 1992, Pyzdrowski et al25 reported that intrahepatic transplant of as few as 265,000 islets was enough to prevent the need for insulin therapy. Since this technique was first described, there have been many advances, and now more than 30 centers worldwide do it.

PRIMARY INDICATION: INTRACTABLE PAIN

Interest has been growing in using total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant to treat recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and hereditary pancreatitis. The rationale is that removing the offending tissue eliminates pancreatitis, pain, and cancer risk, while preserving and replacing the islet cells prevents the development of brittle diabetes with loss of insulin and glucagon.26

Proposed criteria for total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant

Bellin et al14 proposed five criteria for patient selection for this procedure based on imaging studies, pancreatic function tests, and histopathology to detect pancreatic fibrosis. Patients must fulfill all five of the following criteria:

Criterion 1. Diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, based on chronic abdominal pain lasting more than 6 months with either at least one of the following:

- Pancreatic calcifications on computed tomography

- At least two of the following: four or more of nine criteria on endoscopic ultrasonography described by Catalano et al,27 a compatible ductal or parenchymal abnormality on secretin magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; abnormal endoscopic pancreatic function test (peak HCO2 ≤ 80 mmol/L)

- Histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis

- Compatible clinical history and documented hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 gene mutation)

OR

- History of recurrent acute pancreatitis (more than one episode of characteristic pain associated with imaging diagnostic of acute pancreatitis or elevated serum amylase or lipase > 3 times the upper limit of normal).

Criterion 2. At least one of the following:

- Daily narcotic dependence

- Pain resulting in impaired quality of life, which may include inability to attend school, recurrent hospitalizations, or inability to participate in usual age-appropriate activities.

Criterion 3. Complete evaluation with no reversible cause of pancreatitis present or untreated.

Criterion 4. Failure to respond to maximal medical and endoscopic therapy.

Criterion 5. Adequate islet cell function (nondiabetic or C-peptide-positive). Patients with C-peptide-negative diabetes meeting criteria 1 to 4 are candidates for total pancreatectomy alone.

The primary goal is to treat intractable pain and improve quality of life in selected patients with chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis when endoscopic and prior surgical therapies have failed, and whose impairment due to pain is substantial enough to accept the risk of postoperative insulin-dependent diabetes and lifelong commitment to pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.15,26 Patients with a known genetic cause of chronic pancreatitis should be offered special consideration for the procedure, as their disease is unlikely to remit.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant should not be performed in patients with active alcoholism, illicit drug use, or untreated or poorly controlled psychiatric illnesses that could impair the patient’s ability to adhere to a complicated postoperative medical regimen.

A poor support network may be a relative contraindication in view of the cost and complexity of diabetic and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.18,26

Islet cell autotransplant is contraindicated in patients with conditions such as C-peptide-negative or type 1 diabetes or a history of portal vein thrombosis, portal hypertension, significant liver disease, high-risk cardiopulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer (Table 1).26

WHEN TO CONSIDER REFERRAL FOR THIS PROCEDURE

The choice of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant vs conventional surgery must be individualized on the basis of each patient’s anatomy, comorbidities, symptom burden, presence or degree of diabetes, and rate of disease progression. The most important factors to consider in determining the need for and timing of this procedure are the patient’s pain, narcotic requirements, and impaired ability to function.26

Sooner rather than later?

An argument can be made for performing this procedure sooner in the course of the disease rather than later when all else has failed. First, prolonged pain can result in central sensitization, in which the threshold for perceiving pain is lowered by damage to the nociceptive neurons from repeated stimulation and inflammation.28

Further, prolonged opioid therapy can lead to opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which may also render patients more sensitive to pain and aggravate their preexisting pain.26,28

In addition, although operative drainage procedures and partial resections are often considered the gold standard for chronic pancreatitis management, patients who undergo partial pancreatectomy or lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure) have fewer islet cells left to harvest (about 50% fewer) if they subsequently undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.22,26

Therefore, performing this procedure earlier may help the patient avoid chronic pain syndromes and complications of chronic opioid use, including hyperalgesia, and give the best chance of harvesting enough islet cells to prevent or minimize diabetes afterward.11

REMOVING THE PANCREAS, RETURNING THE ISLET CELLS

During this procedure, the blood supply to the pancreas must be preserved until just before its removal to minimize warm ischemia of the islet cells.18,29 Although there are several surgical variations, a pylorus-preserving total pancreatectomy with duodenectomy is typically performed, usually with splenectomy to preserve perfusion to the body and tail.30

The resected pancreas is taken to the islet isolation laboratory. There, the pancreatic duct is cannulated to fill the organ with a cold collagenase solution, followed by gentle mechanical dispersion using the semiautomated Ricordi method,31 which separates the islet cells from the exocrine tissue.32

The number of islet cells is quantified as islet equivalents; 1 islet equivalent is equal to the volume of an islet with a diameter of 150 µm. Islet equivalents per kilogram of body weight is the unit commonly used to report the graft amount transplanted.33

After digestion, the islet cells can be purified or partially purified by a gradient separation method using a Cobe 2991 cell processor (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan),34 or can be transplanted as an unpurified preparation. In islet cell autotransplant for chronic pancreatitis, purification is not always necessary due to the small tissue volume extracted from the often atrophic and fibrotic pancreas.32 The decision to purify depends on the postdigest tissue volume; usually, a tissue volume greater than 0.25 mL/kg body weight is an indication to at least partially purify.18,35

The final preparation is returned to the operating room, and after heparin is given, the islets are infused into the portal system using a stump of the splenic vein, or alternatively through direct puncture of the portal vein or cannulation of the umbilical vein.32,36 If the portal vein pressure reaches 25 cm H2O, the infusion is stopped and the remaining islets can be placed in the peritoneal cavity or elsewhere.18 Transplant of the islets into the liver or peritoneum allows the islets to secrete insulin into the hepatic portal circulation, which is the route used by the native pancreas.22

CONTROLLING GLUCOSE DURING AND AFTER THE PROCEDURE

Animal studies have shown that hyperglycemia impairs islet revascularization,37 and glucose toxicity may cause dysfunction and structural lesions of the transplanted islets.11,38

Therefore, during and after the procedure, most centers maintain euglycemia by an intravenous insulin infusion and subsequently move to subcutaneous insulin when the patient starts eating again. Some centers continue insulin at discharge and gradually taper it over months, even in patients who can possibly achieve euglycemia without it.

OUTCOMES

Many institutions have reported their clinical outcomes in terms of pain relief, islet function, glycemic control, and improvement of quality of life. The largest series have been from the University of Minnesota, Leicester General Hospital, the University of Cincinnati, and the Medical University of South Carolina.

Insulin independence is common but wanes with time

The ability to achieve insulin independence after islet autotransplant appears to be related to the number of islets transplanted, with the best results when more than 2,000 or 3,000 islet equivalents/kg are transplanted.39,40

Sutherland et al18 reported that of 409 patients who underwent islet cell autotransplant at the University of Minnesota (the largest series reported to date), 30% were insulin-independent at 3 years, 33% had partial graft function (defined by positive C-peptide), and 82% achieved a mean hemoglobin A1c of less than 7%. However, in the subset who received more than 5,000 islet equivalents/kg, nearly three-fourths of patients were insulin-independent at 3 years.

The Leicester General Hospital group presented long-term data on 46 patients who underwent total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant. Twelve of the 46 had shown periods of insulin independence for a median of 16.5 months, and 5 remained insulin-free at the time of the publication.41 Over the 10 years of follow-up, insulin requirements and hemoglobin A1c increased notably. However, all of the patients tested C-peptide-positive, suggesting long-lasting graft function.

Most recently, the University of Cincinnati group reported long-term data on 116 patients. The insulin independence rate was 38% at 1 year, decreasing to 27% at 5 years. The number of patients with partial graft function was 38% at 1 year and 35% at 5 years.42

Thus, all three institutions confirmed that the autotransplanted islets continue to secrete insulin long-term, but that function decreases over time.

Pancreatectomy reduces pain

Multiple studies have shown that total pancreatectomy reduces pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ahmad et al43 reported a marked reduction in narcotic use (mean morphine equivalents 206 mg/day before surgery, compared with 90 mg after), and a 58% reduction in pain as demonstrated by narcotic independence.

In the University of Minnesota series, 85% of the 409 patients had less pain at 2 years, and 59% were able to stop taking narcotics.18

The University of Cincinnati group reported a narcotic independence rate of 55% at 1 year, which continued to improve to 73% at 5 years.42

Although the source of pain is removed, pain persists or recurs in 10% to 20% of patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, showing that the pathogenesis of pain is complex, and some uncertainty exists about it.26

Quality of life

Reports evaluating health-related quality of life after total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant are limited.

The University of Cincinnati group reported the long-term outcomes of quality of life as measured by the Short Form 36 Health Survey.42 Ninety-two percent of patients reported overall improvement in their health at 1 year, and 85% continued to report improved health more than 5 years after the surgery.

In a series of 20 patients, 79% to 90% reported improvements in the seven various domains of the Pain Disability Index. In addition, 60% showed improvement in depression and 70% showed improvement in anxiety. The greatest improvements were in those who had not undergone prior pancreatic surgery, who were younger, and in those with higher levels of preoperative pain.30

Similarly, in a series of 74 patients, the Medical University of South Carolina group reported significant improvement in physical and mental health components of the Short Form 12 Health Survey and an associated decrease in daily narcotic requirements. Moreover, the need to start or increase the dose of insulin after the surgery was not associated with a lower quality of life.44

OFF-SITE ISLET CELL ISOLATION

Despite the positive outcomes in terms of pain relief and insulin independence in many patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, few medical centers have an on-site islet-processing facility. Since the mid-1990s, a few centers have been able to circumvent this limitation by working with off-site islet cell isolation laboratories.45,46

The University of California, Los Angeles, first reported on a series of nine patients who received autologous islet cells after near-total or total pancreatectomy using a remote islet cell isolation facility, with results comparable to those of other large institutions.45

Similarly, the procedure has been performed at Cleveland Clinic since 2007 with the collaboration of an off-site islet cell isolation laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. A cohort study from this collaboration published in 2015 showed that in 36 patients (mean follow-up 28 months, range 3–26 months), 33% were insulin-independent, with a C-peptide-positive rate of 70%. This is the largest cohort to date from a center utilizing an off-site islet isolation facility.47

In view of the positive outcomes at these centers, lack of a local islet-processing facility should no longer be a barrier to total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

PATIENT CARE AFTER THE PROCEDURE

A multidisciplinary team is an essential component of the postoperative management of patients who undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

For patients who had been receiving narcotics for a long time before surgery or who were receiving frequent doses, an experienced pain management physician should be involved in the patient’s postoperative care.

Because islet function can wane over time, testing for diabetes should be done at least annually for the rest of the patient’s life and should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and C-peptide, along with self-monitored blood glucose.26

All patients who have surgically induced exocrine insufficiency are at risk of malabsorption and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.48 Hence, lifelong pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is mandatory. Nutritional monitoring should include assessment of steatorrhea, body composition, and fat-soluble vitamin levels (vitamins A, D, and E) at least every year.26 Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk for low bone density from malabsorption of vitamin D and calcium; therefore, it is recommended that a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone density scan be obtained.26,49

Patients who undergo splenectomy as part of their procedure will require appropriate precautions and ongoing vaccinations as recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.26,50,51

WHAT TO EXPECT FOR THE FUTURE

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases has reviewed the potential future research directions for total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant.15

Patient selection remains challenging despite the availability of criteria15 and guidelines.26 More research is needed to better assess preoperative beta-cell function and to predict postoperative outcomes. Mixed meal-tolerance testing is adopted by most clinical centers to predict posttransplant beta-cell function. The use of arginine instead of glucagon in a stimulation test for insulin and C-peptide response has been validated and may allow more accurate assessment.52,53

Another targeted area of research is the advancement of safety and metabolic outcomes. Techniques to minimize warm ischemic time and complications are being evaluated. Islet isolation methods that yield more islets, reduce beta-cell apoptosis, and can isolate islets from glands with malignancy should be further investigated.54 Further, enhanced islet infusion methods that achieve lower portal venous pressures and minimize portal vein thrombosis are needed.

Unfortunately, the function of transplanted islet grafts declines over time. This phenomenon is at least partially attributed to the immediate blood-mediated inflammatory response,55,56 along with islet hypoxia,57 leading to islet apoptosis. Research on different strategies is expanding our knowledge in islet engraftment and posttransplant beta-cell apoptosis, with the expectation that the transplanted islet lifespan will increase. Alternative transplant sites with low inflammatory reaction, such as the omental pouch,58 muscle,59 and bone marrow,60 have shown encouraging data. Other approaches, such as adjuvant anti-inflammatory agents and heparinization, have been proposed.15

Research into complications is also of clinical importance. There is growing attention to hypoglycemia unrelated to exogenous insulin use in posttransplant patients. One hypothesis is that glucagon secretion, a counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia, is defective if the islet cells are transplanted into the liver, and that implanting them into another site may avoid this effect.61

For some patients with chronic pancreatitis, the best option is to remove the entire pancreas. This does not necessarily doom the patient to diabetes mellitus, because we can harvest the islet cells and reinsert them so that, lodged in the liver, they can continue making insulin. However, this approach is underemphasized in the general medical literature and is likely underutilized in the United States.

Here, we discuss chronic pancreatitis, the indications for and contraindications to this procedure, its outcomes, and the management of patients who undergo it.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS IS PROGRESSIVE AND PAINFUL

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive condition characterized by chronic inflammation, irreversible fibrosis, and scarring, resulting in loss of both exocrine and endocrine tissue.

According to a National Institutes of Health database, pancreatitis is the seventh most common digestive disease diagnosis on hospitalization, with annual healthcare costs exceeding $3 billion.1 Although data are scarce, by some estimates the incidence of chronic pancreatitis ranges from 4 to 14 per 100,000 person-years, and the prevalence ranges from 26.4 to 52 per 100,000.2–4 Moreover, a meta-analysis5 found that acute pancreatitis progresses to chronic pancreatitis in 10% of patients who have a first episode of acute pancreatitis and in 36% who have recurrent episodes.

Historically, alcoholism was and still is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis, contributing to 60% to 90% of cases in Western countries.6,7 However, cases due to nonalcoholic causes have been increasing, and in more than one-fourth of patients, no identifiable cause is found.6,8 Smoking is an independent risk factor.6,8,9 Some cases can be linked to genetic abnormalities, particularly in children.10

The clinical manifestations of chronic pancreatitis include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (leading to malnutrition and steatorrhea), endocrine insufficiency (causing diabetes mellitus), and intractable pain.11 Pain is the predominant clinical symptom early in the disease and is often debilitating and difficult to manage. Uncontrolled pain has a devastating impact on quality of life and may become complicated by narcotic dependence.

The pain of chronic pancreatitis is often multifactorial, with mechanisms that include increased intraductal pressure from obstruction of the pancreatic duct, pancreatic ischemia, neuronal injury, and neuroimmune interactions between neuronal processes and chronic inflammation.12

Treatment: Medical and surgical

In chronic pancreatitis, the aim of treatment is to alleviate deficiencies of exocrine and endocrine function and mitigate the pain. Patients who smoke or drink alcohol should be strongly encouraged to quit.

Loss of exocrine function is mainly managed with oral pancreatic enzyme supplements, and diabetes control is often attained with insulin therapy.13 Besides helping digestion, pancreatic enzyme therapy in the form of nonenteric tablets may also reduce pain and pancreatitis attacks.14 The mechanism may be by degrading cholecystokinin-releasing factor in the duodenum, lowering cholecystokinin levels and thereby reducing pain.12

Nonnarcotic analgesics are often the first line of therapy for pain management, but many patients need narcotic analgesics. Along with narcotics, adjunctive agents such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and gabapentinoids have been used to treat chronic pancreatitis pain, but with limited success.15

In patients for whom medical pain management has failed, one can consider another option, such as nerve block, neurolysis, or endoscopic or surgical therapy. Neuromodulators are often prescribed by pain clinics.15 Percutaneous and endoscopic celiac ganglion blocks can be an option but rarely achieve substantial or permanent pain relief, and the induced transient responses (on average 2 to 4 months) often cannot be repeated.14–17

Surgical options to relieve pain try to preserve pancreatic function and vary depending on the degree of severity and nature of pancreatic damage. In broad terms, the surgical procedures can be divided into two types:

- Drainage procedures (eg, pseudocyst drainage; minimally invasive endoscopic duct drainage via sphincterotomy or stent placement, or both; pancreaticojejunostomy)

- Resectional procedures (eg, distal pancreatectomy, isolated head resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy, Whipple procedure, total pancreatectomy).

In carefully selected patients, total pancreatectomy can be offered to remove the cause of the pain.18 This procedure is most often performed in patients who have small-duct disease or a genetic cause or for whom other surgical procedures have failed.11

HISTORY OF THE PROCEDURE

Islet cell transplantation grew out of visionary work by Paul Lacy and David Scharp at the University of Washington at Seattle, whose research focused on isolating and transplanting islet cells in rodent models. The topic has been reviewed by Jahansouz et al.19 In the 1970s, experiments in pancreatectomized dogs showed that transplanting unpurified pancreatic islet tissue that was dispersed by collagenase digestion into the spleen or portal vein could prevent diabetes.20,21 In 1974, the first human trials of transplanting islet cells were conducted, using isolated islets from cadaveric donors to treat diabetes.19

In the past, pancreatectomy was performed to treat painful chronic pancreatitis, but it was viewed as undesirable because removing the gland would inevitably cause insulin-dependent diabetes.22 That changed in 1977 at the University of Minnesota, with the first reported islet cell autotransplant after pancreatectomy. The patient remained pain-free and insulin-independent long-term.23 This seminal case showed that endocrine function could be preserved by autotransplant of islets prepared from the excised pancreas.24

In 1992, Pyzdrowski et al25 reported that intrahepatic transplant of as few as 265,000 islets was enough to prevent the need for insulin therapy. Since this technique was first described, there have been many advances, and now more than 30 centers worldwide do it.

PRIMARY INDICATION: INTRACTABLE PAIN

Interest has been growing in using total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant to treat recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and hereditary pancreatitis. The rationale is that removing the offending tissue eliminates pancreatitis, pain, and cancer risk, while preserving and replacing the islet cells prevents the development of brittle diabetes with loss of insulin and glucagon.26

Proposed criteria for total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant

Bellin et al14 proposed five criteria for patient selection for this procedure based on imaging studies, pancreatic function tests, and histopathology to detect pancreatic fibrosis. Patients must fulfill all five of the following criteria:

Criterion 1. Diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, based on chronic abdominal pain lasting more than 6 months with either at least one of the following:

- Pancreatic calcifications on computed tomography

- At least two of the following: four or more of nine criteria on endoscopic ultrasonography described by Catalano et al,27 a compatible ductal or parenchymal abnormality on secretin magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; abnormal endoscopic pancreatic function test (peak HCO2 ≤ 80 mmol/L)

- Histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis

- Compatible clinical history and documented hereditary pancreatitis (PRSS1 gene mutation)

OR

- History of recurrent acute pancreatitis (more than one episode of characteristic pain associated with imaging diagnostic of acute pancreatitis or elevated serum amylase or lipase > 3 times the upper limit of normal).

Criterion 2. At least one of the following:

- Daily narcotic dependence

- Pain resulting in impaired quality of life, which may include inability to attend school, recurrent hospitalizations, or inability to participate in usual age-appropriate activities.

Criterion 3. Complete evaluation with no reversible cause of pancreatitis present or untreated.

Criterion 4. Failure to respond to maximal medical and endoscopic therapy.

Criterion 5. Adequate islet cell function (nondiabetic or C-peptide-positive). Patients with C-peptide-negative diabetes meeting criteria 1 to 4 are candidates for total pancreatectomy alone.

The primary goal is to treat intractable pain and improve quality of life in selected patients with chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis when endoscopic and prior surgical therapies have failed, and whose impairment due to pain is substantial enough to accept the risk of postoperative insulin-dependent diabetes and lifelong commitment to pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.15,26 Patients with a known genetic cause of chronic pancreatitis should be offered special consideration for the procedure, as their disease is unlikely to remit.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant should not be performed in patients with active alcoholism, illicit drug use, or untreated or poorly controlled psychiatric illnesses that could impair the patient’s ability to adhere to a complicated postoperative medical regimen.

A poor support network may be a relative contraindication in view of the cost and complexity of diabetic and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.18,26

Islet cell autotransplant is contraindicated in patients with conditions such as C-peptide-negative or type 1 diabetes or a history of portal vein thrombosis, portal hypertension, significant liver disease, high-risk cardiopulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer (Table 1).26

WHEN TO CONSIDER REFERRAL FOR THIS PROCEDURE

The choice of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant vs conventional surgery must be individualized on the basis of each patient’s anatomy, comorbidities, symptom burden, presence or degree of diabetes, and rate of disease progression. The most important factors to consider in determining the need for and timing of this procedure are the patient’s pain, narcotic requirements, and impaired ability to function.26

Sooner rather than later?

An argument can be made for performing this procedure sooner in the course of the disease rather than later when all else has failed. First, prolonged pain can result in central sensitization, in which the threshold for perceiving pain is lowered by damage to the nociceptive neurons from repeated stimulation and inflammation.28

Further, prolonged opioid therapy can lead to opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which may also render patients more sensitive to pain and aggravate their preexisting pain.26,28

In addition, although operative drainage procedures and partial resections are often considered the gold standard for chronic pancreatitis management, patients who undergo partial pancreatectomy or lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure) have fewer islet cells left to harvest (about 50% fewer) if they subsequently undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.22,26

Therefore, performing this procedure earlier may help the patient avoid chronic pain syndromes and complications of chronic opioid use, including hyperalgesia, and give the best chance of harvesting enough islet cells to prevent or minimize diabetes afterward.11

REMOVING THE PANCREAS, RETURNING THE ISLET CELLS

During this procedure, the blood supply to the pancreas must be preserved until just before its removal to minimize warm ischemia of the islet cells.18,29 Although there are several surgical variations, a pylorus-preserving total pancreatectomy with duodenectomy is typically performed, usually with splenectomy to preserve perfusion to the body and tail.30

The resected pancreas is taken to the islet isolation laboratory. There, the pancreatic duct is cannulated to fill the organ with a cold collagenase solution, followed by gentle mechanical dispersion using the semiautomated Ricordi method,31 which separates the islet cells from the exocrine tissue.32

The number of islet cells is quantified as islet equivalents; 1 islet equivalent is equal to the volume of an islet with a diameter of 150 µm. Islet equivalents per kilogram of body weight is the unit commonly used to report the graft amount transplanted.33

After digestion, the islet cells can be purified or partially purified by a gradient separation method using a Cobe 2991 cell processor (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan),34 or can be transplanted as an unpurified preparation. In islet cell autotransplant for chronic pancreatitis, purification is not always necessary due to the small tissue volume extracted from the often atrophic and fibrotic pancreas.32 The decision to purify depends on the postdigest tissue volume; usually, a tissue volume greater than 0.25 mL/kg body weight is an indication to at least partially purify.18,35

The final preparation is returned to the operating room, and after heparin is given, the islets are infused into the portal system using a stump of the splenic vein, or alternatively through direct puncture of the portal vein or cannulation of the umbilical vein.32,36 If the portal vein pressure reaches 25 cm H2O, the infusion is stopped and the remaining islets can be placed in the peritoneal cavity or elsewhere.18 Transplant of the islets into the liver or peritoneum allows the islets to secrete insulin into the hepatic portal circulation, which is the route used by the native pancreas.22

CONTROLLING GLUCOSE DURING AND AFTER THE PROCEDURE

Animal studies have shown that hyperglycemia impairs islet revascularization,37 and glucose toxicity may cause dysfunction and structural lesions of the transplanted islets.11,38

Therefore, during and after the procedure, most centers maintain euglycemia by an intravenous insulin infusion and subsequently move to subcutaneous insulin when the patient starts eating again. Some centers continue insulin at discharge and gradually taper it over months, even in patients who can possibly achieve euglycemia without it.

OUTCOMES

Many institutions have reported their clinical outcomes in terms of pain relief, islet function, glycemic control, and improvement of quality of life. The largest series have been from the University of Minnesota, Leicester General Hospital, the University of Cincinnati, and the Medical University of South Carolina.

Insulin independence is common but wanes with time

The ability to achieve insulin independence after islet autotransplant appears to be related to the number of islets transplanted, with the best results when more than 2,000 or 3,000 islet equivalents/kg are transplanted.39,40

Sutherland et al18 reported that of 409 patients who underwent islet cell autotransplant at the University of Minnesota (the largest series reported to date), 30% were insulin-independent at 3 years, 33% had partial graft function (defined by positive C-peptide), and 82% achieved a mean hemoglobin A1c of less than 7%. However, in the subset who received more than 5,000 islet equivalents/kg, nearly three-fourths of patients were insulin-independent at 3 years.

The Leicester General Hospital group presented long-term data on 46 patients who underwent total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant. Twelve of the 46 had shown periods of insulin independence for a median of 16.5 months, and 5 remained insulin-free at the time of the publication.41 Over the 10 years of follow-up, insulin requirements and hemoglobin A1c increased notably. However, all of the patients tested C-peptide-positive, suggesting long-lasting graft function.

Most recently, the University of Cincinnati group reported long-term data on 116 patients. The insulin independence rate was 38% at 1 year, decreasing to 27% at 5 years. The number of patients with partial graft function was 38% at 1 year and 35% at 5 years.42

Thus, all three institutions confirmed that the autotransplanted islets continue to secrete insulin long-term, but that function decreases over time.

Pancreatectomy reduces pain

Multiple studies have shown that total pancreatectomy reduces pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ahmad et al43 reported a marked reduction in narcotic use (mean morphine equivalents 206 mg/day before surgery, compared with 90 mg after), and a 58% reduction in pain as demonstrated by narcotic independence.

In the University of Minnesota series, 85% of the 409 patients had less pain at 2 years, and 59% were able to stop taking narcotics.18

The University of Cincinnati group reported a narcotic independence rate of 55% at 1 year, which continued to improve to 73% at 5 years.42

Although the source of pain is removed, pain persists or recurs in 10% to 20% of patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, showing that the pathogenesis of pain is complex, and some uncertainty exists about it.26

Quality of life

Reports evaluating health-related quality of life after total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant are limited.

The University of Cincinnati group reported the long-term outcomes of quality of life as measured by the Short Form 36 Health Survey.42 Ninety-two percent of patients reported overall improvement in their health at 1 year, and 85% continued to report improved health more than 5 years after the surgery.

In a series of 20 patients, 79% to 90% reported improvements in the seven various domains of the Pain Disability Index. In addition, 60% showed improvement in depression and 70% showed improvement in anxiety. The greatest improvements were in those who had not undergone prior pancreatic surgery, who were younger, and in those with higher levels of preoperative pain.30

Similarly, in a series of 74 patients, the Medical University of South Carolina group reported significant improvement in physical and mental health components of the Short Form 12 Health Survey and an associated decrease in daily narcotic requirements. Moreover, the need to start or increase the dose of insulin after the surgery was not associated with a lower quality of life.44

OFF-SITE ISLET CELL ISOLATION

Despite the positive outcomes in terms of pain relief and insulin independence in many patients after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant, few medical centers have an on-site islet-processing facility. Since the mid-1990s, a few centers have been able to circumvent this limitation by working with off-site islet cell isolation laboratories.45,46

The University of California, Los Angeles, first reported on a series of nine patients who received autologous islet cells after near-total or total pancreatectomy using a remote islet cell isolation facility, with results comparable to those of other large institutions.45

Similarly, the procedure has been performed at Cleveland Clinic since 2007 with the collaboration of an off-site islet cell isolation laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. A cohort study from this collaboration published in 2015 showed that in 36 patients (mean follow-up 28 months, range 3–26 months), 33% were insulin-independent, with a C-peptide-positive rate of 70%. This is the largest cohort to date from a center utilizing an off-site islet isolation facility.47

In view of the positive outcomes at these centers, lack of a local islet-processing facility should no longer be a barrier to total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

PATIENT CARE AFTER THE PROCEDURE

A multidisciplinary team is an essential component of the postoperative management of patients who undergo total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplant.

For patients who had been receiving narcotics for a long time before surgery or who were receiving frequent doses, an experienced pain management physician should be involved in the patient’s postoperative care.

Because islet function can wane over time, testing for diabetes should be done at least annually for the rest of the patient’s life and should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and C-peptide, along with self-monitored blood glucose.26