User login

PTSD: A systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has increasingly become a part of American culture since its introduction in the American Psychiatric Association’s third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980.1 Since then, a proliferation of material about this disorder—both academic and popular—has been generated, yet much confusion persists surrounding the definition of the disorder, its prevalence, and its management. This review addresses the essential elements for diagnosis and treatment of PTSD.

Diagnosis: A closer look at the criteria

Criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD have evolved since 1980, with changes in the definition of trauma and the addition of symptoms and symptom groups.2 Table 13 summarizes the current DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

Trauma exposure. An essential first step in the diagnosis of PTSD is to determine whether the individual has experienced exposure to trauma. This concept is defined in Criterion A (trauma exposure).3 PTSD is nonconformist among the psychiatric diagnoses in that it requires a specific external event as part of its definition. Misapplication of the trauma exposure criterion by many clinicians and researchers has led to misdiagnosis and erroneously high prevalence estimates of PTSD.4,5

A traumatic event is one that represents a threat to life or limb, specifically defined as “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.”3 DSM-5 does not allow for just any stressful event to be considered trauma. For example, no matter how distressing, failing an important test at school or being served with divorce proceedings do not represent a requisite trauma6 because these examples do not entail a threat to life or limb.

DSM-5 PTSD Criterion A also requires a qualifying exposure to the traumatic event. There are 4 types of qualifying exposures:

- direct experience of immediate serious physical danger

- eyewitness of trauma to others

- indirect exposure via violent or accidental trauma experienced by a close family member or close friend

- repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of trauma, such as first responders collecting human remains or law enforcement officers being repeatedly exposed to horrific details of child abuse.3

Witnessed trauma must be in person; thus, viewing trauma in media reports would not constitute a qualifying exposure. Indirect trauma exposure can occur through learning of the experience of a qualifying trauma exposure by a close family member or personal friend.

It is critical to differentiate exposure to trauma (an objective construct) from the subjective distress that may be associated with it. If trauma has not occurred or a qualifying exposure is not established, no amount of distress associated with it can establish the experience as meeting Criterion A for PTSD. This does not mean that nonqualifying experiences of stressful events are not distressing; in fact, such experiences can result in substantial psychological angst. Conversely, exposure to trauma is not tantamount to a diagnosis of PTSD, as most trauma exposures do not result in PTSD.7,8

Continue to: Symptom groups

Symptom groups. DSM-5 symptom criteria for PTSD include 4 symptom groups, Criteria B to E, respectively:

- intrusion

- avoidance

- negative cognitions and mood (numbing)

- hyperarousal/reactivity.

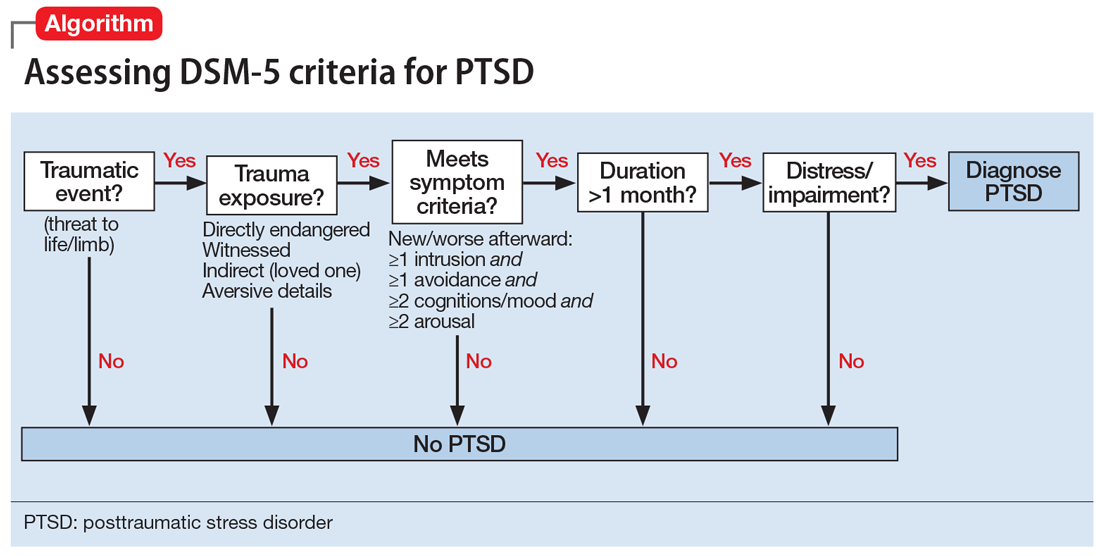

A specific number of symptoms must be present in all 4 of the symptom groups to fulfill diagnostic criteria. Importantly, these symptoms must be linked temporally and conceptually to the traumatic exposure to qualify as PTSD symptoms. Specifically, the symptoms must be new or substantially worsened after the event. For example, continuing sleep disturbance in someone who has had lifetime difficulty sleeping would not count as a trauma-related symptom. Most symptom checklists do not properly assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD because they do not anchor the symptoms in an exposure to a traumatic event; diagnosis requires an interview to fully assess all the diagnostic criteria. Finally, the symptoms must have been present for >1 month for the diagnosis, and the symptoms must have resulted in clinically significant distress or functional impairment to qualify.

The Algorithm provides a practical way to systematically assess all DSM-5 criteria for PTSD to arrive at a diagnosis. The clinician begins by determining whether a traumatic event has occurred and whether the individual had a qualifying exposure to it. If not, PTSD cannot be diagnosed. Alternative diagnoses to consider for new disorders that arise in the context of trauma among patients who are not exposed to trauma include major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, and bereavement, as well as acute stress disorder (which is not validated but has potential utility as a billable diagnosis).

Avoidance and numbing symptoms (present in Criteria C and D) have been shown to represent markers of illness and can be useful in predicting PTSD.8-10 Unlike symptoms of intrusion and hyperarousal (Criteria B and E, respectively), which are very common and by themselves are nonpathological, avoidance/numbing symptoms occur much less commonly, are associated with functional impairment and other indicators of illness, and are strongly associated with PTSD.6 Prominent avoidance/numbing profiles have been demonstrated to predict PTSD in the first 1 to 2 weeks after trauma exposure, before PTSD can be formally diagnosed.11 Posttraumatic stress symptoms are nearly universal after trauma exposure, even in people who do not develop PTSD.5 Intrusion and hyperarousal symptoms constitute most of such symptoms,7 and these symptoms in the absence of prominent avoidance/numbing can be considered normative distress responses to trauma exposure.12

Some PTSD symptoms may seem quite similar to symptoms of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. PTSD can be differentiated from these other disorders by linking the symptoms temporally and contextually to a qualifying exposure to a traumatic event. More often than not, PTSD presents with comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and/or substance use disorders.

Continue to: Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

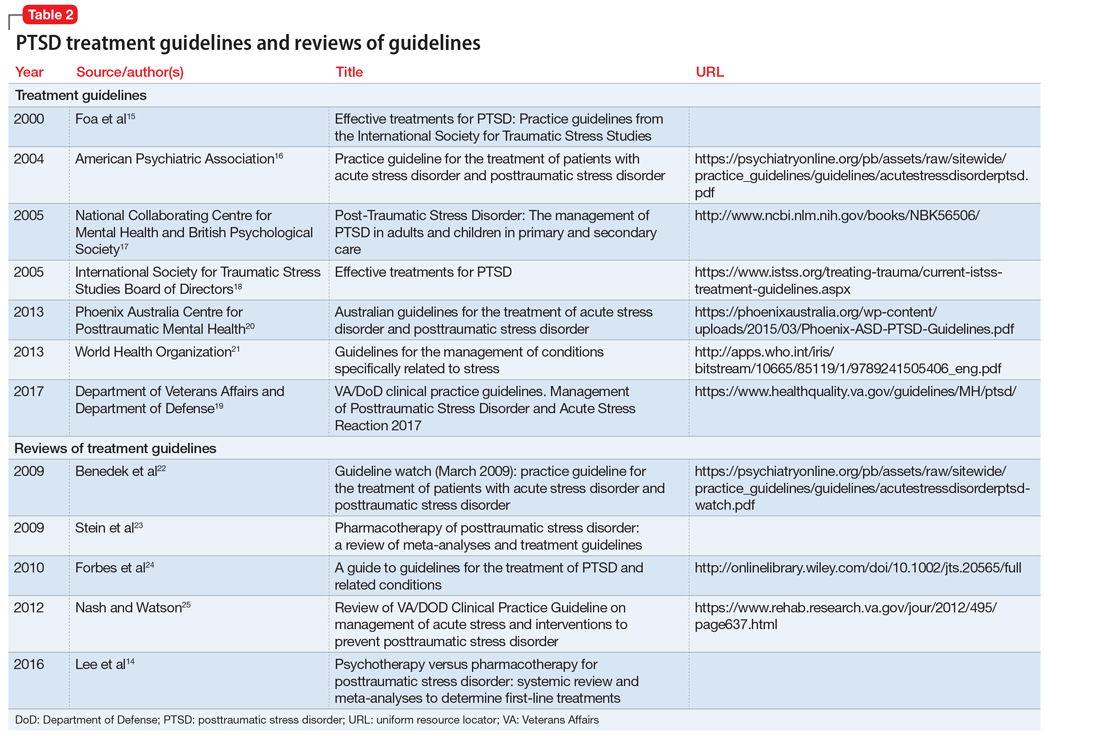

Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy—as monotherapy or in combination—are beneficial for treatment of PTSD. Research has not conclusively shown either treatment modality to be superior, because adequate head-to-head trials have not been conducted.4 Therefore, the choice of initial treatment is based on individual circumstances, such as patient preference for medication and/or psychotherapy, or the availability of therapists trained in evidence-based PTSD psychotherapy. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches are considered especially beneficial for depressive- and anxiety-like symptoms of PTSD, and trauma-focused psychotherapies are presumed to address the neuropathology of conditioned fear and anxiety responses involved in PTSD.14 Table 214-25 provides a list of published treatment guidelines and reviews to help clinicians seeking further detail beyond that provided in this article.

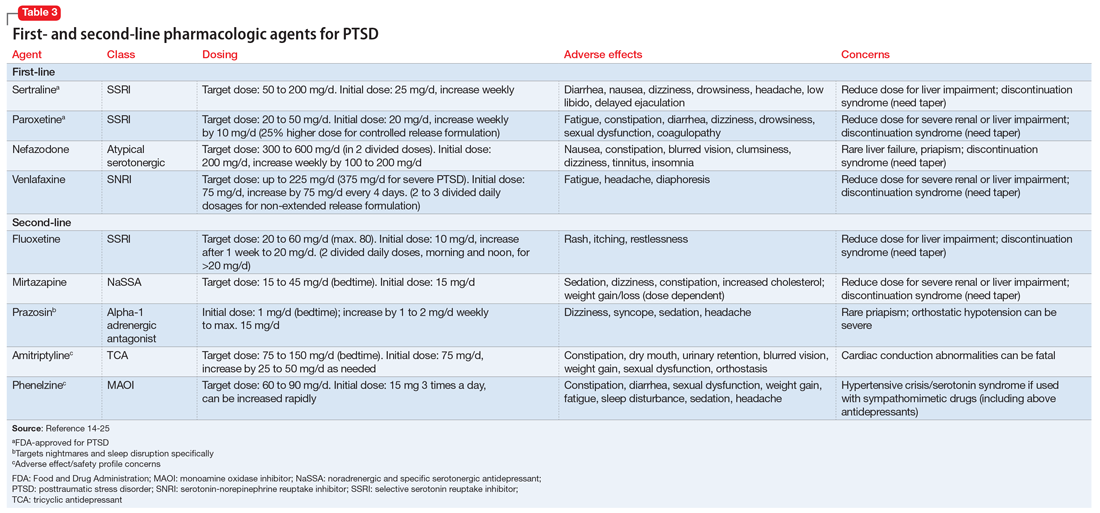

Antidepressants are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These medications are effective for treating major depressive disorder, and have beneficial properties for PTSD independent of their antidepressant effects. The serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for the treatment of PTSD.6 Other recommended medications include the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, and nefazodone, an atypical serotoninergic agent.13 Other antidepressants with less published evidence of effectiveness are used as second-line pharmacotherapies for PTSD, including fluoxetine (SSRI), and mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA).4 Older medications, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline and the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine, have also been used successfully as second-line treatments, but evidence of their benefit is less convincing than that supporting the first-line SSRIs/SNRIs. Additionally, their less favorable adverse effect and safety profiles make them less attractive treatment choices.13 Table 314-25 provides a list of first- and second-line medications for PTSD with recommended dosages and adverse effect profiles.

Other medications. Antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines have not been demonstrated to have efficacy for primary treatment of PTSD, and none of the medications are considered first-line treatments, although sometimes they are used adjunctively in attempts to enhance the effectiveness of antidepressants. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used to target symptoms, such as sleep disturbance or hyperarousal, but only for very short periods. Several authoritative reviews strongly recommend against practices of polypharmacy that commonly involves use of these agents.4,14 Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances, and has grown increasingly popular for treating these symptoms in PTSD, especially in military veterans.13

A well-established barrier to effective pharmacotherapy of PTSD is medication nonadherence.13 Two common underlying sources of nonadherence are inconsistency with the patient’s treatment preference and intolerable adverse effects. Because SSRIs/SNRIs require 8 to 12 weeks of adequate dosing for symptom relief,13 medication adherence is vital. Explaining to patients that it takes many weeks of consistent dosing for clinical effects and reassuring them that the antidepressant agents used to treat PTSD are not habit-forming may help improve adherence.4

Psychotherapy. Prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy—both trauma-focused therapies—have the best empirical evidence for efficacy for PTSD.4,14,26 Some patients are too anxious or avoidant to participate in trauma-focused psychotherapy and may benefit from a course of antidepressant treatment before initiating psychotherapy to reduce hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms enough to allow them to tolerate therapy that incorporates trauma memories.6 However, current PTSD treatment guidelines no longer recommend stabilization with medication or preparatory therapy as a routine prerequisite to trauma-focused psychotherapy.4

Continue to: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy...

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy has emerged as a popular trauma-focused therapy with documented effectiveness. During EMDR, the patient attends to emotionally disturbing material in brief sequential doses (which varies with individual patients) while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus, typically therapist-directed lateral eye movements. Critics of EMDR point out that the theoretical concepts and therapeutic maneuvers (eg, finger movements to guide eye gaze) in EMDR are not consistent with current understanding of the neurobiological processes involved in PTSD. Further, studies testing separate components of the therapy have not established independent effectiveness of the therapeutic maneuvers beyond the therapeutic effects of the psychotherapy components of the procedure.4

Other psychotherapies might also be beneficial, but not enough research has been conducted to provide evidence for their effectiveness.4 Non-trauma–focused psychotherapies used for PTSD include supportive therapy, motivational interviewing, relaxation, and mindfulness. Because these therapies have less evidence of effectiveness, they are now widely considered second-line options. Psychological first aid is not a treatment for PTSD, but rather a nontreatment intervention for distress that is widely used by first responders and crisis counselors to provide compassion, support, and stabilization for people exposed to trauma, whether or not they have developed PTSD. Psychological first aid is supported by expert consensus, but it has not been studied enough to demonstrate how helpful it is as a treatment.6

Comorbidities require careful consideration

PTSD in the presence of other psychiatric disorders may require a unique and specialized approach to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. For instance, for a patient who has a comorbid substance use disorder, acute substance withdrawal can exacerbate PTSD symptoms. Sertraline is considered a medication of choice for these patients,13 and having a substance abuse specialist on the treatment team is desirable.4,13 A patient with comorbid traumatic brain injury (TBI) may have reduced tolerance to medications, and may require an individually-tailored and elongated titration strategy. Additionally, stimulants sometimes used to improve cognition for patients with comorbid TBI can exacerbate symptoms of hyperarousal, and these patients may need stabilization before beginning PTSD treatment. Antidepressant treatment for PTSD among patients with comorbid bipolar disorder has the potential to induce mania. Psychiatrists must consider these issues when formulating treatment plans for patients with PTSD and specific psychiatric comorbidities.4,6

PTSD symptoms can be chronic, sometimes lasting many years or even decades.27 In a longitudinal study of 716 survivors of 10 different disasters, 62% of those diagnosed with PTSD were still symptomatic 1 to 3 years after the disaster, demonstrating the enduring nature of PTSD symptoms.12 Similarly, a follow-up study of survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing found 58% of those with PTSD and 39% of those without PTSD were still reporting posttraumatic stress symptoms 7 years after the incident.28 Remarkably, these same individuals reported substantially improved functioning at work, with family and personal activities, and social interactions,28 and long-term employment disability specifically related to PTSD is highly unusual.29 Even individuals who continued to report active posttraumatic stress symptoms experienced a return of functioning equivalent to levels in individuals with no PTSD.28 These data suggest that treating psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can be optimistic that functioning can improve remarkably over the long term, even if posttraumatic stress symptoms persist.

Bottom Line

A thorough understanding of the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Evidence-based treatment options for adults with PTSD include certain antidepressants and trauma-focused psychotherapies.

Related Resources

- Bernadino M, Nelson KJ. FIGHT to remember PTSD. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):17.

- Koola MM. Prazosin and doxazosin for PTSD are underutilized and underdosed. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):19-20,47,e1.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac, Sarafem

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nefazodone • Serzone

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Prazosin • Minipress

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

2. North CS, Surís AM, Smith RP, et al. The evolution of PTSD criteria across editions of the DSM. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):197-208.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

4. Downs DL, North CS. Trauma-related disorders. Overview of posttraumatic stress disorder. https://www.deckerip.com/products/scientific-american-psychiatry/table-of-contents/. Published July 2017. Accessed February 27, 2018.

5. North CS. Disaster mental health epidemiology: methodological review and interpretation of research findings. Psychiatry. 2016; 79(2):130-146.

6. North CS, Yutzy SH. Goodwin and Guze’s Psychiatric Diagnosis, 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, et al. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1999;282(8):755-762.

8. North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental Health Response to Community Disasters: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2013;310(5):507-518.

9. North CS, Pollio DE, Smith, RP, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among employees of New York City companies affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(suppl 2):S205-S213.

10. North CS, Oliver J, Pandya A. Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e40-e48.

11. Whitman JB, North CS, Downs DL, et al. A prospective study of the onset of PTSD symptoms in the first month after trauma exposure. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(3):163-172.

12. North CS, Oliver J. Analysis of the longitudinal course of PTSD in 716 survivors of 10 disasters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(8):1189-1197.

13. Jeffreys M, Capehart B, Friedman MJ. Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: review with clinical applications. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):703-715.

14. Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, et al. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: systemic review and meta-analyses to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):792-806.

15. Foa EB, Keane T, Friedman MJ. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for traumatic stress studies. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2000.

16. Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, et al; Work Group on ASD and PTSD. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2004.

17. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London, UK: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society; 2005.

18. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, eds; The Board of Directors of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2nd ed. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Guilford Press; 2005.

19. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction 2017. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/. Published June 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

20. Phoenix Australia -Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Melbourne, Australia: Phoenix Australia Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health; 2013.

21. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press; 2013.

22. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):201-213.

23. Stein DJ, Ipser J, McAnda N. Pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of meta-analyses and treatment guidelines. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(suppl 1):25-31.

24. Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):537-552.

25. Nash WP, Watson PJ. Review of VA/DOD clinical practice guideline on management of acute stress and interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):637-648.

26. Birur B, Moore NC, Davis LL. An evidence-based review of early intervention and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(2):183-201.

27. Breslau N, Davis GC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: Risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):671-675.

28. North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Kawasaki A, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of directly exposed survivors seven years after the Oklahoma City bombing. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):1-8

29. Rasco SS, North CS. An empirical study of employment and disability over three years among survivors of major disasters. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(1):80-86.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has increasingly become a part of American culture since its introduction in the American Psychiatric Association’s third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980.1 Since then, a proliferation of material about this disorder—both academic and popular—has been generated, yet much confusion persists surrounding the definition of the disorder, its prevalence, and its management. This review addresses the essential elements for diagnosis and treatment of PTSD.

Diagnosis: A closer look at the criteria

Criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD have evolved since 1980, with changes in the definition of trauma and the addition of symptoms and symptom groups.2 Table 13 summarizes the current DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

Trauma exposure. An essential first step in the diagnosis of PTSD is to determine whether the individual has experienced exposure to trauma. This concept is defined in Criterion A (trauma exposure).3 PTSD is nonconformist among the psychiatric diagnoses in that it requires a specific external event as part of its definition. Misapplication of the trauma exposure criterion by many clinicians and researchers has led to misdiagnosis and erroneously high prevalence estimates of PTSD.4,5

A traumatic event is one that represents a threat to life or limb, specifically defined as “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.”3 DSM-5 does not allow for just any stressful event to be considered trauma. For example, no matter how distressing, failing an important test at school or being served with divorce proceedings do not represent a requisite trauma6 because these examples do not entail a threat to life or limb.

DSM-5 PTSD Criterion A also requires a qualifying exposure to the traumatic event. There are 4 types of qualifying exposures:

- direct experience of immediate serious physical danger

- eyewitness of trauma to others

- indirect exposure via violent or accidental trauma experienced by a close family member or close friend

- repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of trauma, such as first responders collecting human remains or law enforcement officers being repeatedly exposed to horrific details of child abuse.3

Witnessed trauma must be in person; thus, viewing trauma in media reports would not constitute a qualifying exposure. Indirect trauma exposure can occur through learning of the experience of a qualifying trauma exposure by a close family member or personal friend.

It is critical to differentiate exposure to trauma (an objective construct) from the subjective distress that may be associated with it. If trauma has not occurred or a qualifying exposure is not established, no amount of distress associated with it can establish the experience as meeting Criterion A for PTSD. This does not mean that nonqualifying experiences of stressful events are not distressing; in fact, such experiences can result in substantial psychological angst. Conversely, exposure to trauma is not tantamount to a diagnosis of PTSD, as most trauma exposures do not result in PTSD.7,8

Continue to: Symptom groups

Symptom groups. DSM-5 symptom criteria for PTSD include 4 symptom groups, Criteria B to E, respectively:

- intrusion

- avoidance

- negative cognitions and mood (numbing)

- hyperarousal/reactivity.

A specific number of symptoms must be present in all 4 of the symptom groups to fulfill diagnostic criteria. Importantly, these symptoms must be linked temporally and conceptually to the traumatic exposure to qualify as PTSD symptoms. Specifically, the symptoms must be new or substantially worsened after the event. For example, continuing sleep disturbance in someone who has had lifetime difficulty sleeping would not count as a trauma-related symptom. Most symptom checklists do not properly assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD because they do not anchor the symptoms in an exposure to a traumatic event; diagnosis requires an interview to fully assess all the diagnostic criteria. Finally, the symptoms must have been present for >1 month for the diagnosis, and the symptoms must have resulted in clinically significant distress or functional impairment to qualify.

The Algorithm provides a practical way to systematically assess all DSM-5 criteria for PTSD to arrive at a diagnosis. The clinician begins by determining whether a traumatic event has occurred and whether the individual had a qualifying exposure to it. If not, PTSD cannot be diagnosed. Alternative diagnoses to consider for new disorders that arise in the context of trauma among patients who are not exposed to trauma include major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, and bereavement, as well as acute stress disorder (which is not validated but has potential utility as a billable diagnosis).

Avoidance and numbing symptoms (present in Criteria C and D) have been shown to represent markers of illness and can be useful in predicting PTSD.8-10 Unlike symptoms of intrusion and hyperarousal (Criteria B and E, respectively), which are very common and by themselves are nonpathological, avoidance/numbing symptoms occur much less commonly, are associated with functional impairment and other indicators of illness, and are strongly associated with PTSD.6 Prominent avoidance/numbing profiles have been demonstrated to predict PTSD in the first 1 to 2 weeks after trauma exposure, before PTSD can be formally diagnosed.11 Posttraumatic stress symptoms are nearly universal after trauma exposure, even in people who do not develop PTSD.5 Intrusion and hyperarousal symptoms constitute most of such symptoms,7 and these symptoms in the absence of prominent avoidance/numbing can be considered normative distress responses to trauma exposure.12

Some PTSD symptoms may seem quite similar to symptoms of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. PTSD can be differentiated from these other disorders by linking the symptoms temporally and contextually to a qualifying exposure to a traumatic event. More often than not, PTSD presents with comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and/or substance use disorders.

Continue to: Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy—as monotherapy or in combination—are beneficial for treatment of PTSD. Research has not conclusively shown either treatment modality to be superior, because adequate head-to-head trials have not been conducted.4 Therefore, the choice of initial treatment is based on individual circumstances, such as patient preference for medication and/or psychotherapy, or the availability of therapists trained in evidence-based PTSD psychotherapy. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches are considered especially beneficial for depressive- and anxiety-like symptoms of PTSD, and trauma-focused psychotherapies are presumed to address the neuropathology of conditioned fear and anxiety responses involved in PTSD.14 Table 214-25 provides a list of published treatment guidelines and reviews to help clinicians seeking further detail beyond that provided in this article.

Antidepressants are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These medications are effective for treating major depressive disorder, and have beneficial properties for PTSD independent of their antidepressant effects. The serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for the treatment of PTSD.6 Other recommended medications include the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, and nefazodone, an atypical serotoninergic agent.13 Other antidepressants with less published evidence of effectiveness are used as second-line pharmacotherapies for PTSD, including fluoxetine (SSRI), and mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA).4 Older medications, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline and the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine, have also been used successfully as second-line treatments, but evidence of their benefit is less convincing than that supporting the first-line SSRIs/SNRIs. Additionally, their less favorable adverse effect and safety profiles make them less attractive treatment choices.13 Table 314-25 provides a list of first- and second-line medications for PTSD with recommended dosages and adverse effect profiles.

Other medications. Antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines have not been demonstrated to have efficacy for primary treatment of PTSD, and none of the medications are considered first-line treatments, although sometimes they are used adjunctively in attempts to enhance the effectiveness of antidepressants. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used to target symptoms, such as sleep disturbance or hyperarousal, but only for very short periods. Several authoritative reviews strongly recommend against practices of polypharmacy that commonly involves use of these agents.4,14 Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances, and has grown increasingly popular for treating these symptoms in PTSD, especially in military veterans.13

A well-established barrier to effective pharmacotherapy of PTSD is medication nonadherence.13 Two common underlying sources of nonadherence are inconsistency with the patient’s treatment preference and intolerable adverse effects. Because SSRIs/SNRIs require 8 to 12 weeks of adequate dosing for symptom relief,13 medication adherence is vital. Explaining to patients that it takes many weeks of consistent dosing for clinical effects and reassuring them that the antidepressant agents used to treat PTSD are not habit-forming may help improve adherence.4

Psychotherapy. Prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy—both trauma-focused therapies—have the best empirical evidence for efficacy for PTSD.4,14,26 Some patients are too anxious or avoidant to participate in trauma-focused psychotherapy and may benefit from a course of antidepressant treatment before initiating psychotherapy to reduce hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms enough to allow them to tolerate therapy that incorporates trauma memories.6 However, current PTSD treatment guidelines no longer recommend stabilization with medication or preparatory therapy as a routine prerequisite to trauma-focused psychotherapy.4

Continue to: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy...

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy has emerged as a popular trauma-focused therapy with documented effectiveness. During EMDR, the patient attends to emotionally disturbing material in brief sequential doses (which varies with individual patients) while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus, typically therapist-directed lateral eye movements. Critics of EMDR point out that the theoretical concepts and therapeutic maneuvers (eg, finger movements to guide eye gaze) in EMDR are not consistent with current understanding of the neurobiological processes involved in PTSD. Further, studies testing separate components of the therapy have not established independent effectiveness of the therapeutic maneuvers beyond the therapeutic effects of the psychotherapy components of the procedure.4

Other psychotherapies might also be beneficial, but not enough research has been conducted to provide evidence for their effectiveness.4 Non-trauma–focused psychotherapies used for PTSD include supportive therapy, motivational interviewing, relaxation, and mindfulness. Because these therapies have less evidence of effectiveness, they are now widely considered second-line options. Psychological first aid is not a treatment for PTSD, but rather a nontreatment intervention for distress that is widely used by first responders and crisis counselors to provide compassion, support, and stabilization for people exposed to trauma, whether or not they have developed PTSD. Psychological first aid is supported by expert consensus, but it has not been studied enough to demonstrate how helpful it is as a treatment.6

Comorbidities require careful consideration

PTSD in the presence of other psychiatric disorders may require a unique and specialized approach to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. For instance, for a patient who has a comorbid substance use disorder, acute substance withdrawal can exacerbate PTSD symptoms. Sertraline is considered a medication of choice for these patients,13 and having a substance abuse specialist on the treatment team is desirable.4,13 A patient with comorbid traumatic brain injury (TBI) may have reduced tolerance to medications, and may require an individually-tailored and elongated titration strategy. Additionally, stimulants sometimes used to improve cognition for patients with comorbid TBI can exacerbate symptoms of hyperarousal, and these patients may need stabilization before beginning PTSD treatment. Antidepressant treatment for PTSD among patients with comorbid bipolar disorder has the potential to induce mania. Psychiatrists must consider these issues when formulating treatment plans for patients with PTSD and specific psychiatric comorbidities.4,6

PTSD symptoms can be chronic, sometimes lasting many years or even decades.27 In a longitudinal study of 716 survivors of 10 different disasters, 62% of those diagnosed with PTSD were still symptomatic 1 to 3 years after the disaster, demonstrating the enduring nature of PTSD symptoms.12 Similarly, a follow-up study of survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing found 58% of those with PTSD and 39% of those without PTSD were still reporting posttraumatic stress symptoms 7 years after the incident.28 Remarkably, these same individuals reported substantially improved functioning at work, with family and personal activities, and social interactions,28 and long-term employment disability specifically related to PTSD is highly unusual.29 Even individuals who continued to report active posttraumatic stress symptoms experienced a return of functioning equivalent to levels in individuals with no PTSD.28 These data suggest that treating psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can be optimistic that functioning can improve remarkably over the long term, even if posttraumatic stress symptoms persist.

Bottom Line

A thorough understanding of the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Evidence-based treatment options for adults with PTSD include certain antidepressants and trauma-focused psychotherapies.

Related Resources

- Bernadino M, Nelson KJ. FIGHT to remember PTSD. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):17.

- Koola MM. Prazosin and doxazosin for PTSD are underutilized and underdosed. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):19-20,47,e1.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac, Sarafem

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nefazodone • Serzone

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Prazosin • Minipress

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has increasingly become a part of American culture since its introduction in the American Psychiatric Association’s third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980.1 Since then, a proliferation of material about this disorder—both academic and popular—has been generated, yet much confusion persists surrounding the definition of the disorder, its prevalence, and its management. This review addresses the essential elements for diagnosis and treatment of PTSD.

Diagnosis: A closer look at the criteria

Criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD have evolved since 1980, with changes in the definition of trauma and the addition of symptoms and symptom groups.2 Table 13 summarizes the current DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

Trauma exposure. An essential first step in the diagnosis of PTSD is to determine whether the individual has experienced exposure to trauma. This concept is defined in Criterion A (trauma exposure).3 PTSD is nonconformist among the psychiatric diagnoses in that it requires a specific external event as part of its definition. Misapplication of the trauma exposure criterion by many clinicians and researchers has led to misdiagnosis and erroneously high prevalence estimates of PTSD.4,5

A traumatic event is one that represents a threat to life or limb, specifically defined as “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.”3 DSM-5 does not allow for just any stressful event to be considered trauma. For example, no matter how distressing, failing an important test at school or being served with divorce proceedings do not represent a requisite trauma6 because these examples do not entail a threat to life or limb.

DSM-5 PTSD Criterion A also requires a qualifying exposure to the traumatic event. There are 4 types of qualifying exposures:

- direct experience of immediate serious physical danger

- eyewitness of trauma to others

- indirect exposure via violent or accidental trauma experienced by a close family member or close friend

- repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of trauma, such as first responders collecting human remains or law enforcement officers being repeatedly exposed to horrific details of child abuse.3

Witnessed trauma must be in person; thus, viewing trauma in media reports would not constitute a qualifying exposure. Indirect trauma exposure can occur through learning of the experience of a qualifying trauma exposure by a close family member or personal friend.

It is critical to differentiate exposure to trauma (an objective construct) from the subjective distress that may be associated with it. If trauma has not occurred or a qualifying exposure is not established, no amount of distress associated with it can establish the experience as meeting Criterion A for PTSD. This does not mean that nonqualifying experiences of stressful events are not distressing; in fact, such experiences can result in substantial psychological angst. Conversely, exposure to trauma is not tantamount to a diagnosis of PTSD, as most trauma exposures do not result in PTSD.7,8

Continue to: Symptom groups

Symptom groups. DSM-5 symptom criteria for PTSD include 4 symptom groups, Criteria B to E, respectively:

- intrusion

- avoidance

- negative cognitions and mood (numbing)

- hyperarousal/reactivity.

A specific number of symptoms must be present in all 4 of the symptom groups to fulfill diagnostic criteria. Importantly, these symptoms must be linked temporally and conceptually to the traumatic exposure to qualify as PTSD symptoms. Specifically, the symptoms must be new or substantially worsened after the event. For example, continuing sleep disturbance in someone who has had lifetime difficulty sleeping would not count as a trauma-related symptom. Most symptom checklists do not properly assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD because they do not anchor the symptoms in an exposure to a traumatic event; diagnosis requires an interview to fully assess all the diagnostic criteria. Finally, the symptoms must have been present for >1 month for the diagnosis, and the symptoms must have resulted in clinically significant distress or functional impairment to qualify.

The Algorithm provides a practical way to systematically assess all DSM-5 criteria for PTSD to arrive at a diagnosis. The clinician begins by determining whether a traumatic event has occurred and whether the individual had a qualifying exposure to it. If not, PTSD cannot be diagnosed. Alternative diagnoses to consider for new disorders that arise in the context of trauma among patients who are not exposed to trauma include major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, and bereavement, as well as acute stress disorder (which is not validated but has potential utility as a billable diagnosis).

Avoidance and numbing symptoms (present in Criteria C and D) have been shown to represent markers of illness and can be useful in predicting PTSD.8-10 Unlike symptoms of intrusion and hyperarousal (Criteria B and E, respectively), which are very common and by themselves are nonpathological, avoidance/numbing symptoms occur much less commonly, are associated with functional impairment and other indicators of illness, and are strongly associated with PTSD.6 Prominent avoidance/numbing profiles have been demonstrated to predict PTSD in the first 1 to 2 weeks after trauma exposure, before PTSD can be formally diagnosed.11 Posttraumatic stress symptoms are nearly universal after trauma exposure, even in people who do not develop PTSD.5 Intrusion and hyperarousal symptoms constitute most of such symptoms,7 and these symptoms in the absence of prominent avoidance/numbing can be considered normative distress responses to trauma exposure.12

Some PTSD symptoms may seem quite similar to symptoms of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. PTSD can be differentiated from these other disorders by linking the symptoms temporally and contextually to a qualifying exposure to a traumatic event. More often than not, PTSD presents with comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and/or substance use disorders.

Continue to: Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy—as monotherapy or in combination—are beneficial for treatment of PTSD. Research has not conclusively shown either treatment modality to be superior, because adequate head-to-head trials have not been conducted.4 Therefore, the choice of initial treatment is based on individual circumstances, such as patient preference for medication and/or psychotherapy, or the availability of therapists trained in evidence-based PTSD psychotherapy. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches are considered especially beneficial for depressive- and anxiety-like symptoms of PTSD, and trauma-focused psychotherapies are presumed to address the neuropathology of conditioned fear and anxiety responses involved in PTSD.14 Table 214-25 provides a list of published treatment guidelines and reviews to help clinicians seeking further detail beyond that provided in this article.

Antidepressants are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These medications are effective for treating major depressive disorder, and have beneficial properties for PTSD independent of their antidepressant effects. The serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for the treatment of PTSD.6 Other recommended medications include the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, and nefazodone, an atypical serotoninergic agent.13 Other antidepressants with less published evidence of effectiveness are used as second-line pharmacotherapies for PTSD, including fluoxetine (SSRI), and mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA).4 Older medications, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline and the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine, have also been used successfully as second-line treatments, but evidence of their benefit is less convincing than that supporting the first-line SSRIs/SNRIs. Additionally, their less favorable adverse effect and safety profiles make them less attractive treatment choices.13 Table 314-25 provides a list of first- and second-line medications for PTSD with recommended dosages and adverse effect profiles.

Other medications. Antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines have not been demonstrated to have efficacy for primary treatment of PTSD, and none of the medications are considered first-line treatments, although sometimes they are used adjunctively in attempts to enhance the effectiveness of antidepressants. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used to target symptoms, such as sleep disturbance or hyperarousal, but only for very short periods. Several authoritative reviews strongly recommend against practices of polypharmacy that commonly involves use of these agents.4,14 Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances, and has grown increasingly popular for treating these symptoms in PTSD, especially in military veterans.13

A well-established barrier to effective pharmacotherapy of PTSD is medication nonadherence.13 Two common underlying sources of nonadherence are inconsistency with the patient’s treatment preference and intolerable adverse effects. Because SSRIs/SNRIs require 8 to 12 weeks of adequate dosing for symptom relief,13 medication adherence is vital. Explaining to patients that it takes many weeks of consistent dosing for clinical effects and reassuring them that the antidepressant agents used to treat PTSD are not habit-forming may help improve adherence.4

Psychotherapy. Prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy—both trauma-focused therapies—have the best empirical evidence for efficacy for PTSD.4,14,26 Some patients are too anxious or avoidant to participate in trauma-focused psychotherapy and may benefit from a course of antidepressant treatment before initiating psychotherapy to reduce hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms enough to allow them to tolerate therapy that incorporates trauma memories.6 However, current PTSD treatment guidelines no longer recommend stabilization with medication or preparatory therapy as a routine prerequisite to trauma-focused psychotherapy.4

Continue to: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy...

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy has emerged as a popular trauma-focused therapy with documented effectiveness. During EMDR, the patient attends to emotionally disturbing material in brief sequential doses (which varies with individual patients) while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus, typically therapist-directed lateral eye movements. Critics of EMDR point out that the theoretical concepts and therapeutic maneuvers (eg, finger movements to guide eye gaze) in EMDR are not consistent with current understanding of the neurobiological processes involved in PTSD. Further, studies testing separate components of the therapy have not established independent effectiveness of the therapeutic maneuvers beyond the therapeutic effects of the psychotherapy components of the procedure.4

Other psychotherapies might also be beneficial, but not enough research has been conducted to provide evidence for their effectiveness.4 Non-trauma–focused psychotherapies used for PTSD include supportive therapy, motivational interviewing, relaxation, and mindfulness. Because these therapies have less evidence of effectiveness, they are now widely considered second-line options. Psychological first aid is not a treatment for PTSD, but rather a nontreatment intervention for distress that is widely used by first responders and crisis counselors to provide compassion, support, and stabilization for people exposed to trauma, whether or not they have developed PTSD. Psychological first aid is supported by expert consensus, but it has not been studied enough to demonstrate how helpful it is as a treatment.6

Comorbidities require careful consideration

PTSD in the presence of other psychiatric disorders may require a unique and specialized approach to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. For instance, for a patient who has a comorbid substance use disorder, acute substance withdrawal can exacerbate PTSD symptoms. Sertraline is considered a medication of choice for these patients,13 and having a substance abuse specialist on the treatment team is desirable.4,13 A patient with comorbid traumatic brain injury (TBI) may have reduced tolerance to medications, and may require an individually-tailored and elongated titration strategy. Additionally, stimulants sometimes used to improve cognition for patients with comorbid TBI can exacerbate symptoms of hyperarousal, and these patients may need stabilization before beginning PTSD treatment. Antidepressant treatment for PTSD among patients with comorbid bipolar disorder has the potential to induce mania. Psychiatrists must consider these issues when formulating treatment plans for patients with PTSD and specific psychiatric comorbidities.4,6

PTSD symptoms can be chronic, sometimes lasting many years or even decades.27 In a longitudinal study of 716 survivors of 10 different disasters, 62% of those diagnosed with PTSD were still symptomatic 1 to 3 years after the disaster, demonstrating the enduring nature of PTSD symptoms.12 Similarly, a follow-up study of survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing found 58% of those with PTSD and 39% of those without PTSD were still reporting posttraumatic stress symptoms 7 years after the incident.28 Remarkably, these same individuals reported substantially improved functioning at work, with family and personal activities, and social interactions,28 and long-term employment disability specifically related to PTSD is highly unusual.29 Even individuals who continued to report active posttraumatic stress symptoms experienced a return of functioning equivalent to levels in individuals with no PTSD.28 These data suggest that treating psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can be optimistic that functioning can improve remarkably over the long term, even if posttraumatic stress symptoms persist.

Bottom Line

A thorough understanding of the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Evidence-based treatment options for adults with PTSD include certain antidepressants and trauma-focused psychotherapies.

Related Resources

- Bernadino M, Nelson KJ. FIGHT to remember PTSD. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):17.

- Koola MM. Prazosin and doxazosin for PTSD are underutilized and underdosed. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):19-20,47,e1.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac, Sarafem

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nefazodone • Serzone

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Prazosin • Minipress

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

2. North CS, Surís AM, Smith RP, et al. The evolution of PTSD criteria across editions of the DSM. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):197-208.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

4. Downs DL, North CS. Trauma-related disorders. Overview of posttraumatic stress disorder. https://www.deckerip.com/products/scientific-american-psychiatry/table-of-contents/. Published July 2017. Accessed February 27, 2018.

5. North CS. Disaster mental health epidemiology: methodological review and interpretation of research findings. Psychiatry. 2016; 79(2):130-146.

6. North CS, Yutzy SH. Goodwin and Guze’s Psychiatric Diagnosis, 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, et al. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1999;282(8):755-762.

8. North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental Health Response to Community Disasters: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2013;310(5):507-518.

9. North CS, Pollio DE, Smith, RP, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among employees of New York City companies affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(suppl 2):S205-S213.

10. North CS, Oliver J, Pandya A. Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e40-e48.

11. Whitman JB, North CS, Downs DL, et al. A prospective study of the onset of PTSD symptoms in the first month after trauma exposure. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(3):163-172.

12. North CS, Oliver J. Analysis of the longitudinal course of PTSD in 716 survivors of 10 disasters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(8):1189-1197.

13. Jeffreys M, Capehart B, Friedman MJ. Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: review with clinical applications. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):703-715.

14. Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, et al. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: systemic review and meta-analyses to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):792-806.

15. Foa EB, Keane T, Friedman MJ. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for traumatic stress studies. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2000.

16. Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, et al; Work Group on ASD and PTSD. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2004.

17. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London, UK: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society; 2005.

18. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, eds; The Board of Directors of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2nd ed. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Guilford Press; 2005.

19. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction 2017. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/. Published June 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

20. Phoenix Australia -Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Melbourne, Australia: Phoenix Australia Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health; 2013.

21. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press; 2013.

22. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):201-213.

23. Stein DJ, Ipser J, McAnda N. Pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of meta-analyses and treatment guidelines. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(suppl 1):25-31.

24. Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):537-552.

25. Nash WP, Watson PJ. Review of VA/DOD clinical practice guideline on management of acute stress and interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):637-648.

26. Birur B, Moore NC, Davis LL. An evidence-based review of early intervention and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(2):183-201.

27. Breslau N, Davis GC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: Risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):671-675.

28. North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Kawasaki A, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of directly exposed survivors seven years after the Oklahoma City bombing. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):1-8

29. Rasco SS, North CS. An empirical study of employment and disability over three years among survivors of major disasters. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(1):80-86.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

2. North CS, Surís AM, Smith RP, et al. The evolution of PTSD criteria across editions of the DSM. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):197-208.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

4. Downs DL, North CS. Trauma-related disorders. Overview of posttraumatic stress disorder. https://www.deckerip.com/products/scientific-american-psychiatry/table-of-contents/. Published July 2017. Accessed February 27, 2018.

5. North CS. Disaster mental health epidemiology: methodological review and interpretation of research findings. Psychiatry. 2016; 79(2):130-146.

6. North CS, Yutzy SH. Goodwin and Guze’s Psychiatric Diagnosis, 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, et al. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1999;282(8):755-762.

8. North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental Health Response to Community Disasters: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2013;310(5):507-518.

9. North CS, Pollio DE, Smith, RP, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among employees of New York City companies affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(suppl 2):S205-S213.

10. North CS, Oliver J, Pandya A. Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e40-e48.

11. Whitman JB, North CS, Downs DL, et al. A prospective study of the onset of PTSD symptoms in the first month after trauma exposure. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(3):163-172.

12. North CS, Oliver J. Analysis of the longitudinal course of PTSD in 716 survivors of 10 disasters. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(8):1189-1197.

13. Jeffreys M, Capehart B, Friedman MJ. Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: review with clinical applications. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):703-715.

14. Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, et al. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: systemic review and meta-analyses to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):792-806.

15. Foa EB, Keane T, Friedman MJ. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for traumatic stress studies. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2000.

16. Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, et al; Work Group on ASD and PTSD. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2004.

17. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London, UK: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society; 2005.

18. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, eds; The Board of Directors of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2nd ed. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Guilford Press; 2005.

19. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction 2017. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/. Published June 2017. Accessed February 26, 2018.

20. Phoenix Australia -Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Melbourne, Australia: Phoenix Australia Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health; 2013.

21. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Press; 2013.

22. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):201-213.

23. Stein DJ, Ipser J, McAnda N. Pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of meta-analyses and treatment guidelines. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(suppl 1):25-31.

24. Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):537-552.

25. Nash WP, Watson PJ. Review of VA/DOD clinical practice guideline on management of acute stress and interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(5):637-648.

26. Birur B, Moore NC, Davis LL. An evidence-based review of early intervention and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(2):183-201.

27. Breslau N, Davis GC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: Risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):671-675.

28. North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Kawasaki A, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of directly exposed survivors seven years after the Oklahoma City bombing. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):1-8

29. Rasco SS, North CS. An empirical study of employment and disability over three years among survivors of major disasters. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(1):80-86.