User login

What should I address at follow-up of patients who survive critical illness?

Patients who survive critical illness such as shock or respiratory failure warranting admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) often develop a constellation of chronic symptoms including cognitive decline, psychiatric disturbances, and physical weakness. These changes can prevent patients from returning to their former level of function and often necessitate significant support for patients and their caregivers.1

With growing awareness of the unique needs of ICU survivors, multidisciplinary PICS clinics have emerged. However, access to these clinics is limited, and most patients discharged from the ICU eventually follow up with their primary care provider. Primary care physicians who recognize PICS, understand its prognosis and its burden on caregivers, and are aware of tools that have shown promise in its management will be well prepared to address the needs of these patients.

COGNITIVE DECLINE

Several studies have shown that survivors of critical illness suffer from long-term impairment of multiple domains of cognition, including executive function. In one study, 40% of ICU survivors had global cognition scores at 1 year after discharge that were worse than those seen in moderate traumatic brain injury, and over 25% had scores similar to those seen in Alzheimer dementia.2 Age had poor correlation with the incidence of long-term cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment may not be recognized in younger patients without a high index of suspicion and directed cognitive screening. Well-known cognitive impairment screening tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment may help in the evaluation of PICS.

No treatment has been shown to improve long-term cognitive impairment from any cause. The most important intervention is to recognize it and to consider how impaired executive function may interfere with other aspects of treatment, such as participation in physical therapy and adherence to medication regimens.

Evidence is also emerging that patients are often inappropriately discharged on psychoactive medications (including atypical antipsychotic drugs and sedatives) that were started in the inpatient setting.7 These medications increase the risk of accidents, arrhythmia, and infection, as well as add to the overall cost of postdischarge care, and they do not improve the prolonged confusion and cognitive impairment associated with PICS.8 Psychoactive medications should be discontinued once delirium-associated behavior has resolved, as recommended in the American Geriatrics Society guideline on postoperative delirium.9 Further, patients and caregivers should be counseled so that they have reasonable expectations regarding the timing of cognitive recovery, which may be prolonged and incomplete.

PHYSICAL WEAKNESS

Prolonged physical weakness may affect up to one-third of patients who survive critical illness, and it may persist for years, severely compromising quality of life.10 In addition to deconditioning due to bedrest and illness, ICU patients often develop critical illness myopathy and critical illness polyneuropathy.

Although the mechanisms and risk factors for injury to muscles and peripheral nerves are not completely understood, the severity has been well described and ranges from proximal muscle weakness to complete quadriparesis, with inability to wean from mechanical ventilation. There is also an association with the severity of sepsis and the use of glucocorticoids and paralytics.10

Physical weakness can be readily apparent on routine history and physical examination. Differentiating critical illness myopathy from critical illness polyneuropathy requires invasive testing, including electromyography, but the results may not change management in the outpatient setting, making it unnecessary for most patients.

Physical weakness places a heavy burden on patients and their family and caregivers. As a result, most ICU patients suffer loss of employment and require supportive services on discharge, including home health aides and even institutionalization.

Physical therapy and occupational therapy are effective in reducing weakness and improving physical functioning; starting physical therapy in the outpatient setting may be as effective as early intervention in the ICU.11 Given the high prevalence of respiratory and cardiovascular disease in patients after ICU discharge, referral for pulmonary or cardiovascular rehabilitation is recommended. Because of the possible link between glucocorticoids and critical illness myopathy, these drugs should be decreased or discontinued as soon as possible.

PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES

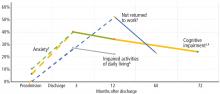

Mental health impairments in ICU survivors are common, severe, debilitating, and unfortunately, commonly overlooked. A recent study found a 37% incidence of depression and a 40% incidence of anxiety; further, 22% of patients met criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder.12 Patients with critical illness are also more likely to have had untreated mental health illness before hospitalization. Anxiety may present with poor sleep, irritability, and fatigue. Posttraumatic stress disorder may manifest as flashbacks or as a severe cognitive or behavioral response to provocation. All of these may be assessed using standard screening questionnaires, including the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) for depression, and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screen (GAD-7).

Many primary care physicians are comfortable treating some of the psychiatric disturbances associated with PICS, such as depression, but may be challenged by the spectrum and complexity of mental illness of ICU survivors. Early referral to a mental health professional ensures optimal psychiatric care and allows more time to focus on the patient’s medical comorbidities.

SOCIAL SUPPORT

The cognitive, physical, and mental health complications coupled with other medical and psychiatric comorbidities result in serious social and financial stress on patients and their families. Long-term follow-up studies show that only half of patients return to work within 1 year of critical illness and that nearly one-fourth require continued assistance with activities of daily living.13 Reassuringly, however, most patients in 1 study had returned to work by 2 years from discharge.3

The immense burden on caregivers, the decrease in income, and increased expenditures in providing care result in increased stress on families. The incidence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder is similar among patients and their caregivers.11 The frequency of emotional morbidity and the severity of the caregiver burden associated with caring for ICU survivors led to the description of a new entity: post-intensive care syndrome-family, or PICS-F.

Because of these stresses, patients often benefit from referral to a social worker. Patients should also be encouraged to bring their caregivers to physician appointments, and family members should be encouraged to discuss their perspectives in the context of a dedicated appointment. Family members should also be screened and treated for their own medical and mental health challenges. A dedicated ICU survivorship clinic may help facilitate this holistic approach and provide complementary services to the primary care provider.

CRITICAL CARE RECOVERY

As survival rates after critical illness continue to improve and clinicians encounter more patients with PICS, it is essential to appreciate the extent of associated physical, emotional, and financial hardship and to recognize when cognitive impairment may interfere with treatment. Early and accurate recognition of these challenges can help the primary care physician arrange and coordinate recovery services that ICU survivors require. Including family members in follow-up appointments can help overcome challenges in adherence to treatment plans, uncover gaps in social support, and identify signs of caregiver distress.

A thorough physical assessment and a thoughtful reconciliation of medications are critical, as is engaging the assistance of physical and occupational therapists, mental health professionals, and social workers.

Risk factors for the illness that necessitated the ICU stay such as uncontrolled diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and substance abuse, as well as medical sequelae such as chronic respiratory failure and heart failure, must be considered and addressed by the primary care physician, with referral to medical specialists if necessary.

Referral to an ICU survivorship center, if locally available, could help the physician manage the patient’s complex and multidisciplinary physical and neuropsychiatric needs. The Society of Critical Care Medicine maintains a resource for survivors and families at www.myicucare.org/thrive/pages/find-in-person-support-groups.aspx.

- Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012; 40(2):502–509. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al; BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(14):1306–1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301372

- Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(14):1293–1304. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011802

- Rothenhäusler H-B, Ehrentraut S, Stoll C, Schelling G, Kapfhammer H-P. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001; 23(2):90–96. pmid:11313077

- Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016; 43:23–29. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005

- Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al; Bringing to light the Risk Factors And Incidence of Neuropsychological dysfunction in ICU survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2(5):369–379. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7

- Morandi A, Vasilevskis E, Pandharipande PP, et al. Inappropriate medication prescriptions in elderly adults surviving an intensive care unit hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61(7):1128–1134. doi:10.1111/jgs.12329

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. American Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(1):142–150. doi:10.1111/jgs.13281

- Hermans G, Van den Berghe G. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Crit Care 2015; 19:274. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0993-7

- Calvo-Ayala E, Khan BA, Farber MO, Ely EW, Boustani MA. Interventions to improve the physical function of ICU survivors: a systematic review. Chest 2013; 144(5):1469–1480. doi:10.1378/chest.13-0779

- Wang S, Allen D, Kheir YN, Campbell N, Khan B. Aging and post-intensive care syndrome: a critical need for geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 26(2):212–221. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.016

- Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(7):1554–1561. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2c8b1

- van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Dongelmans DA, van der Schaaf M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care 2016; 20:16. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1185-9

Patients who survive critical illness such as shock or respiratory failure warranting admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) often develop a constellation of chronic symptoms including cognitive decline, psychiatric disturbances, and physical weakness. These changes can prevent patients from returning to their former level of function and often necessitate significant support for patients and their caregivers.1

With growing awareness of the unique needs of ICU survivors, multidisciplinary PICS clinics have emerged. However, access to these clinics is limited, and most patients discharged from the ICU eventually follow up with their primary care provider. Primary care physicians who recognize PICS, understand its prognosis and its burden on caregivers, and are aware of tools that have shown promise in its management will be well prepared to address the needs of these patients.

COGNITIVE DECLINE

Several studies have shown that survivors of critical illness suffer from long-term impairment of multiple domains of cognition, including executive function. In one study, 40% of ICU survivors had global cognition scores at 1 year after discharge that were worse than those seen in moderate traumatic brain injury, and over 25% had scores similar to those seen in Alzheimer dementia.2 Age had poor correlation with the incidence of long-term cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment may not be recognized in younger patients without a high index of suspicion and directed cognitive screening. Well-known cognitive impairment screening tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment may help in the evaluation of PICS.

No treatment has been shown to improve long-term cognitive impairment from any cause. The most important intervention is to recognize it and to consider how impaired executive function may interfere with other aspects of treatment, such as participation in physical therapy and adherence to medication regimens.

Evidence is also emerging that patients are often inappropriately discharged on psychoactive medications (including atypical antipsychotic drugs and sedatives) that were started in the inpatient setting.7 These medications increase the risk of accidents, arrhythmia, and infection, as well as add to the overall cost of postdischarge care, and they do not improve the prolonged confusion and cognitive impairment associated with PICS.8 Psychoactive medications should be discontinued once delirium-associated behavior has resolved, as recommended in the American Geriatrics Society guideline on postoperative delirium.9 Further, patients and caregivers should be counseled so that they have reasonable expectations regarding the timing of cognitive recovery, which may be prolonged and incomplete.

PHYSICAL WEAKNESS

Prolonged physical weakness may affect up to one-third of patients who survive critical illness, and it may persist for years, severely compromising quality of life.10 In addition to deconditioning due to bedrest and illness, ICU patients often develop critical illness myopathy and critical illness polyneuropathy.

Although the mechanisms and risk factors for injury to muscles and peripheral nerves are not completely understood, the severity has been well described and ranges from proximal muscle weakness to complete quadriparesis, with inability to wean from mechanical ventilation. There is also an association with the severity of sepsis and the use of glucocorticoids and paralytics.10

Physical weakness can be readily apparent on routine history and physical examination. Differentiating critical illness myopathy from critical illness polyneuropathy requires invasive testing, including electromyography, but the results may not change management in the outpatient setting, making it unnecessary for most patients.

Physical weakness places a heavy burden on patients and their family and caregivers. As a result, most ICU patients suffer loss of employment and require supportive services on discharge, including home health aides and even institutionalization.

Physical therapy and occupational therapy are effective in reducing weakness and improving physical functioning; starting physical therapy in the outpatient setting may be as effective as early intervention in the ICU.11 Given the high prevalence of respiratory and cardiovascular disease in patients after ICU discharge, referral for pulmonary or cardiovascular rehabilitation is recommended. Because of the possible link between glucocorticoids and critical illness myopathy, these drugs should be decreased or discontinued as soon as possible.

PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES

Mental health impairments in ICU survivors are common, severe, debilitating, and unfortunately, commonly overlooked. A recent study found a 37% incidence of depression and a 40% incidence of anxiety; further, 22% of patients met criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder.12 Patients with critical illness are also more likely to have had untreated mental health illness before hospitalization. Anxiety may present with poor sleep, irritability, and fatigue. Posttraumatic stress disorder may manifest as flashbacks or as a severe cognitive or behavioral response to provocation. All of these may be assessed using standard screening questionnaires, including the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) for depression, and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screen (GAD-7).

Many primary care physicians are comfortable treating some of the psychiatric disturbances associated with PICS, such as depression, but may be challenged by the spectrum and complexity of mental illness of ICU survivors. Early referral to a mental health professional ensures optimal psychiatric care and allows more time to focus on the patient’s medical comorbidities.

SOCIAL SUPPORT

The cognitive, physical, and mental health complications coupled with other medical and psychiatric comorbidities result in serious social and financial stress on patients and their families. Long-term follow-up studies show that only half of patients return to work within 1 year of critical illness and that nearly one-fourth require continued assistance with activities of daily living.13 Reassuringly, however, most patients in 1 study had returned to work by 2 years from discharge.3

The immense burden on caregivers, the decrease in income, and increased expenditures in providing care result in increased stress on families. The incidence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder is similar among patients and their caregivers.11 The frequency of emotional morbidity and the severity of the caregiver burden associated with caring for ICU survivors led to the description of a new entity: post-intensive care syndrome-family, or PICS-F.

Because of these stresses, patients often benefit from referral to a social worker. Patients should also be encouraged to bring their caregivers to physician appointments, and family members should be encouraged to discuss their perspectives in the context of a dedicated appointment. Family members should also be screened and treated for their own medical and mental health challenges. A dedicated ICU survivorship clinic may help facilitate this holistic approach and provide complementary services to the primary care provider.

CRITICAL CARE RECOVERY

As survival rates after critical illness continue to improve and clinicians encounter more patients with PICS, it is essential to appreciate the extent of associated physical, emotional, and financial hardship and to recognize when cognitive impairment may interfere with treatment. Early and accurate recognition of these challenges can help the primary care physician arrange and coordinate recovery services that ICU survivors require. Including family members in follow-up appointments can help overcome challenges in adherence to treatment plans, uncover gaps in social support, and identify signs of caregiver distress.

A thorough physical assessment and a thoughtful reconciliation of medications are critical, as is engaging the assistance of physical and occupational therapists, mental health professionals, and social workers.

Risk factors for the illness that necessitated the ICU stay such as uncontrolled diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and substance abuse, as well as medical sequelae such as chronic respiratory failure and heart failure, must be considered and addressed by the primary care physician, with referral to medical specialists if necessary.

Referral to an ICU survivorship center, if locally available, could help the physician manage the patient’s complex and multidisciplinary physical and neuropsychiatric needs. The Society of Critical Care Medicine maintains a resource for survivors and families at www.myicucare.org/thrive/pages/find-in-person-support-groups.aspx.

Patients who survive critical illness such as shock or respiratory failure warranting admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) often develop a constellation of chronic symptoms including cognitive decline, psychiatric disturbances, and physical weakness. These changes can prevent patients from returning to their former level of function and often necessitate significant support for patients and their caregivers.1

With growing awareness of the unique needs of ICU survivors, multidisciplinary PICS clinics have emerged. However, access to these clinics is limited, and most patients discharged from the ICU eventually follow up with their primary care provider. Primary care physicians who recognize PICS, understand its prognosis and its burden on caregivers, and are aware of tools that have shown promise in its management will be well prepared to address the needs of these patients.

COGNITIVE DECLINE

Several studies have shown that survivors of critical illness suffer from long-term impairment of multiple domains of cognition, including executive function. In one study, 40% of ICU survivors had global cognition scores at 1 year after discharge that were worse than those seen in moderate traumatic brain injury, and over 25% had scores similar to those seen in Alzheimer dementia.2 Age had poor correlation with the incidence of long-term cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment may not be recognized in younger patients without a high index of suspicion and directed cognitive screening. Well-known cognitive impairment screening tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment may help in the evaluation of PICS.

No treatment has been shown to improve long-term cognitive impairment from any cause. The most important intervention is to recognize it and to consider how impaired executive function may interfere with other aspects of treatment, such as participation in physical therapy and adherence to medication regimens.

Evidence is also emerging that patients are often inappropriately discharged on psychoactive medications (including atypical antipsychotic drugs and sedatives) that were started in the inpatient setting.7 These medications increase the risk of accidents, arrhythmia, and infection, as well as add to the overall cost of postdischarge care, and they do not improve the prolonged confusion and cognitive impairment associated with PICS.8 Psychoactive medications should be discontinued once delirium-associated behavior has resolved, as recommended in the American Geriatrics Society guideline on postoperative delirium.9 Further, patients and caregivers should be counseled so that they have reasonable expectations regarding the timing of cognitive recovery, which may be prolonged and incomplete.

PHYSICAL WEAKNESS

Prolonged physical weakness may affect up to one-third of patients who survive critical illness, and it may persist for years, severely compromising quality of life.10 In addition to deconditioning due to bedrest and illness, ICU patients often develop critical illness myopathy and critical illness polyneuropathy.

Although the mechanisms and risk factors for injury to muscles and peripheral nerves are not completely understood, the severity has been well described and ranges from proximal muscle weakness to complete quadriparesis, with inability to wean from mechanical ventilation. There is also an association with the severity of sepsis and the use of glucocorticoids and paralytics.10

Physical weakness can be readily apparent on routine history and physical examination. Differentiating critical illness myopathy from critical illness polyneuropathy requires invasive testing, including electromyography, but the results may not change management in the outpatient setting, making it unnecessary for most patients.

Physical weakness places a heavy burden on patients and their family and caregivers. As a result, most ICU patients suffer loss of employment and require supportive services on discharge, including home health aides and even institutionalization.

Physical therapy and occupational therapy are effective in reducing weakness and improving physical functioning; starting physical therapy in the outpatient setting may be as effective as early intervention in the ICU.11 Given the high prevalence of respiratory and cardiovascular disease in patients after ICU discharge, referral for pulmonary or cardiovascular rehabilitation is recommended. Because of the possible link between glucocorticoids and critical illness myopathy, these drugs should be decreased or discontinued as soon as possible.

PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES

Mental health impairments in ICU survivors are common, severe, debilitating, and unfortunately, commonly overlooked. A recent study found a 37% incidence of depression and a 40% incidence of anxiety; further, 22% of patients met criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder.12 Patients with critical illness are also more likely to have had untreated mental health illness before hospitalization. Anxiety may present with poor sleep, irritability, and fatigue. Posttraumatic stress disorder may manifest as flashbacks or as a severe cognitive or behavioral response to provocation. All of these may be assessed using standard screening questionnaires, including the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) for depression, and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screen (GAD-7).

Many primary care physicians are comfortable treating some of the psychiatric disturbances associated with PICS, such as depression, but may be challenged by the spectrum and complexity of mental illness of ICU survivors. Early referral to a mental health professional ensures optimal psychiatric care and allows more time to focus on the patient’s medical comorbidities.

SOCIAL SUPPORT

The cognitive, physical, and mental health complications coupled with other medical and psychiatric comorbidities result in serious social and financial stress on patients and their families. Long-term follow-up studies show that only half of patients return to work within 1 year of critical illness and that nearly one-fourth require continued assistance with activities of daily living.13 Reassuringly, however, most patients in 1 study had returned to work by 2 years from discharge.3

The immense burden on caregivers, the decrease in income, and increased expenditures in providing care result in increased stress on families. The incidence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder is similar among patients and their caregivers.11 The frequency of emotional morbidity and the severity of the caregiver burden associated with caring for ICU survivors led to the description of a new entity: post-intensive care syndrome-family, or PICS-F.

Because of these stresses, patients often benefit from referral to a social worker. Patients should also be encouraged to bring their caregivers to physician appointments, and family members should be encouraged to discuss their perspectives in the context of a dedicated appointment. Family members should also be screened and treated for their own medical and mental health challenges. A dedicated ICU survivorship clinic may help facilitate this holistic approach and provide complementary services to the primary care provider.

CRITICAL CARE RECOVERY

As survival rates after critical illness continue to improve and clinicians encounter more patients with PICS, it is essential to appreciate the extent of associated physical, emotional, and financial hardship and to recognize when cognitive impairment may interfere with treatment. Early and accurate recognition of these challenges can help the primary care physician arrange and coordinate recovery services that ICU survivors require. Including family members in follow-up appointments can help overcome challenges in adherence to treatment plans, uncover gaps in social support, and identify signs of caregiver distress.

A thorough physical assessment and a thoughtful reconciliation of medications are critical, as is engaging the assistance of physical and occupational therapists, mental health professionals, and social workers.

Risk factors for the illness that necessitated the ICU stay such as uncontrolled diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and substance abuse, as well as medical sequelae such as chronic respiratory failure and heart failure, must be considered and addressed by the primary care physician, with referral to medical specialists if necessary.

Referral to an ICU survivorship center, if locally available, could help the physician manage the patient’s complex and multidisciplinary physical and neuropsychiatric needs. The Society of Critical Care Medicine maintains a resource for survivors and families at www.myicucare.org/thrive/pages/find-in-person-support-groups.aspx.

- Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012; 40(2):502–509. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al; BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(14):1306–1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301372

- Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(14):1293–1304. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011802

- Rothenhäusler H-B, Ehrentraut S, Stoll C, Schelling G, Kapfhammer H-P. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001; 23(2):90–96. pmid:11313077

- Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016; 43:23–29. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005

- Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al; Bringing to light the Risk Factors And Incidence of Neuropsychological dysfunction in ICU survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2(5):369–379. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7

- Morandi A, Vasilevskis E, Pandharipande PP, et al. Inappropriate medication prescriptions in elderly adults surviving an intensive care unit hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61(7):1128–1134. doi:10.1111/jgs.12329

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. American Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(1):142–150. doi:10.1111/jgs.13281

- Hermans G, Van den Berghe G. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Crit Care 2015; 19:274. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0993-7

- Calvo-Ayala E, Khan BA, Farber MO, Ely EW, Boustani MA. Interventions to improve the physical function of ICU survivors: a systematic review. Chest 2013; 144(5):1469–1480. doi:10.1378/chest.13-0779

- Wang S, Allen D, Kheir YN, Campbell N, Khan B. Aging and post-intensive care syndrome: a critical need for geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 26(2):212–221. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.016

- Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(7):1554–1561. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2c8b1

- van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Dongelmans DA, van der Schaaf M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care 2016; 20:16. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1185-9

- Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012; 40(2):502–509. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al; BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(14):1306–1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301372

- Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(14):1293–1304. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011802

- Rothenhäusler H-B, Ehrentraut S, Stoll C, Schelling G, Kapfhammer H-P. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001; 23(2):90–96. pmid:11313077

- Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016; 43:23–29. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005

- Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al; Bringing to light the Risk Factors And Incidence of Neuropsychological dysfunction in ICU survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2(5):369–379. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7

- Morandi A, Vasilevskis E, Pandharipande PP, et al. Inappropriate medication prescriptions in elderly adults surviving an intensive care unit hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61(7):1128–1134. doi:10.1111/jgs.12329

- Johnson KG, Fashoyin A, Madden-Fuentes R, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Yanamadala M. Discharge plans for geriatric inpatients with delirium: a plan to stop antipsychotics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65(10):2278–2281. doi:10.1111/jgs.15026

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. American Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(1):142–150. doi:10.1111/jgs.13281

- Hermans G, Van den Berghe G. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Crit Care 2015; 19:274. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0993-7

- Calvo-Ayala E, Khan BA, Farber MO, Ely EW, Boustani MA. Interventions to improve the physical function of ICU survivors: a systematic review. Chest 2013; 144(5):1469–1480. doi:10.1378/chest.13-0779

- Wang S, Allen D, Kheir YN, Campbell N, Khan B. Aging and post-intensive care syndrome: a critical need for geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 26(2):212–221. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.016

- Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(7):1554–1561. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2c8b1

- van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Dongelmans DA, van der Schaaf M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care 2016; 20:16. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1185-9