User login

Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Reconstruction of the Anterolateral Ligament: Surgical Technique and Case Report

Restoring native kinematics of the knee has been a primary goal of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) procedures. Double-bundle ACL reconstruction, compared to single-bundle, has been hypothesized to more effectively re-establish rotational stability by re-creating the anatomic ACL, but has not yet proven to result in better clinical outcomes.1

In 1879, Dr. Paul Segond described a “fibrous, pearly band” at the lateral aspect of the knee that avulsed off the anterolateral proximal tibia during many ACL injuries.2 The role of the lateral tissues in knee stability and their relationship with ACL pathology has attracted noteworthy attention in recent time. There have been multiple studies presenting an anatomical description of a structure at the anterolateral portion of the knee with definitive femoral, meniscal, and tibial attachments, which helps control internal rotational forces.3-7 Claes and colleagues4 later found that band of tissue to be the anterolateral ligament (ALL) and determined its injury to be pathognomonic with ACL ruptures.

The ALL is a vital static stabilizer of the tibio-femoral joint, especially during internal tibial rotation.8-10 In their report on ALL and ACL reconstruction, Helito and colleagues11 acknowledge the necessity of accurate assessment of the lateral structures through imaging to determine the presence of extra-articular injury. Musculoskeletal diagnostic ultrasound has been established as an appropriate means to identify the ALL.12

Ultrasound can accurately determine the exact anatomic location of the origin and insertion of the ALL. Reconstruction of the ALL could yield better patient outcomes for those who experience concurrent ACL/ALL injury. Here we present an innovative technique for an ultrasound-guided percutaneous method for reconstruction of the ALL and report on a patient who had underwent ALL reconstruction.

Surgical Indications

All patients undergo an ultrasound evaluation preoperatively to determine if the ALL is intact or injured. Our experience has shown that when ultrasound evaluation reveals an intact ALL, the pivot shift has never been a grade III.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, see the video that accompanies this article.

The pivot shift test is conducted under anesthesia to determine whether an ALL reconstruction is required. The patient is placed in a supine position with the knee flexed at 30o, at neutral rotation, and without any varus or valgus stress.

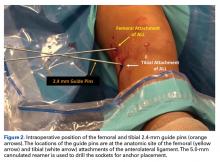

A No. 15 blade is used to make a small incision centered on each spinal needle. The spinal needle is replaced with a 2.4-mm drill pin (Figure 2).

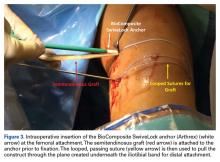

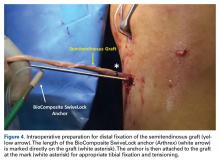

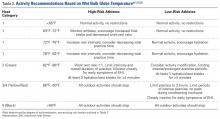

The graft and FiberTape are then passed under the IT band to the distal incision. Using the length of the BioComposite SwiveLock anchor as a guide, a mark is made on the graft after tensioning the construct in line with the leg, distal to the tibial drill pin (Table 2, Figure 4).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation following an ALL procedure is similar to traditional ACL rehabilitation with an added emphasis on minimizing rotational torque of the tibia in the early stages.

Case Report

In January 2013, a 17-year-old male soccer player suffered an ACL rupture of his right knee. Later that spring, he had an ACL reconstruction with an allograft. Twelve months postoperatively, the patient returned, saying that he felt much better; however, anytime he tried to plant his foot and rotate over that fixed foot, his knee felt unstable. The physical examination revealed both negative Lachman and anterior drawer tests but a I+ pivot shift test. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination revealed an intact ACL graft. A diagnostic ultrasound evaluation revealed a distal ALL injury. After discussing the risks, benefits, and goals with the patient, we opted for a diagnostic arthroscopy and a percutaneous, ultrasound-guided reconstruction of the ALL.

Postoperatively, the patient did very well. One week after surgery, he returned, saying he felt completely stable and demonstrated by repeating the rotation of his knee. The patient continued to have no issues until he returned 13 months post-ALL surgery, complaining of a recent injury that had caused the return of his feelings of instability. An MRI evaluation showed an intact ACL graft and the possibility of a ruptured ALL. Fifteen months after the initial ALL reconstruction, we proceeded with surgery. At arthroscopy, the patient was found to have a pivot shift of I+ and an intact ACL graft. The ALL was reconstructed again using an allograft, internal brace, and bone marrow concentrate. At 13 months post-ALL reconstruction revision, the patient had no complaints.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the ALL is aimed to restore anatomic rotational kinematics. Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues14 have reported promising initial results in their 2-year follow-up study of combined ACL and ALL reconstruction outcomes. This surgical technique includes use of an internal brace, which negates the necessity for external support devices and allows for earlier mobilization of the joint. A reconstruction of the ALL, performed concurrently with the ACL, does not add recovery time, but could prevent postsurgical complications and improve rehabilitation by eliminating rotational instability that presents in some ACL-reconstructed patients.

Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues15 state that their arthroscopic identification of the ALL can help to cultivate a “less invasive and more anatomic” reconstruction. The use of musculoskeletal ultrasound allows our technique to utilize a completely noninvasive imaging tool that allows proper establishment of ALL anatomy prior to the procedure. The entirety of the ALL is easily identifiable,4,12 which has proven to be shortcoming of MRI evaluation.15-17 Accurate preoperative assessment of the lateral structures is necessary in ACL-deficient individuals.11,15 Sonography also provides a means of accurate guidance and socket creation, without generating large incisions.

If the ALL is responsible for internal rotatory stability as asserted, the structure should exhibit biomechanical properties during movement. In their study on the function of the ligament, Parsons and colleagues9 established the inverse relationship between the ALL and ACL during internal rotation. As their cadaveric knees were subjected to an internal rotatory force through increasing angles of flexion, the contribution of the ALL towards stability significantly increased while the ACL declined. Helito and colleagues8 and Zens and colleagues10 have demonstrated length changes of the ligament through varying degrees of flexion and internal rotation. Their reports indicate greater tension during knee movements, coinciding with the description of increasing ALL stability contribution by Parsons and colleagues.9 Kennedy and colleagues7 conducted a pull-to-failure test on the ALL. The average failure load was 175 N with a stiffness of 20 N/mm, illustrating the structure is a candidate for most traditional soft tissue grafts. The biomechanical evidence of the structural properties of the ALL confirms its importance in knee function and the necessity for its reconstruction.

With the understanding that ACL contributes to rotatory stability to some extent, the notion begs the question of how a centrally located ligament is able to prevent excessive rotation in a structure with a large relative radius. Biomechanically, with such a small moment arm, the ACL would experience tremendous stress when a rotatory force is applied. The same torque applied to a more superficial structure, with a greater moment, would sustain a large reduction in the applied force. The concept of a wheel and an axle should be considered. The equation is F1 × R1 = F2 × R2. We measured on a cadaveric knee the distance from the center of rotation to the ACL and the ALL, finding the radii were 5 mm and 30 mm, respectively. Taking these measurements, we would then expect the force experienced on the axle (ACL) to be 6 times greater than what would be experienced on the periphery of the wheel (ALL). The ALL (wheel) has a significant biomechanical advantage over the ACL (axle) in controlling and enduring internal rotatory forces of the knee. This would imply that if the ALL were damaged and not re-established, the ACL would experience a 6 times greater force trying to control internal rotation, which would result in a significantly increased chance of failure and rupture.

While there is a degree of dissent on the presence of the ALL, a number of studies have classified the tissue as an independent ligamentous structure.3-7 While there is disagreement on the precise location of the femoral attachment, there is a consensus on the location of the tibial and meniscal attachments. Claes and colleagues4 originally outlined the femoral attachment as anterior and distal to the origin of the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), which is the description this technique follows. Since Claes and colleagues’4 report, many have investigated the ligament’s femoral origin with delineations ranging from posterior and proximal3,5,7 to anterior and distal.6,16-18

The accurate, noninvasive nature of the musculoskeletal ultrasound prior to any incisions being made makes this technique innovative and superior to other open surgical techniques or those that require fluoroscopy.

Conclusion

The ALL has been determined to play an integral role in the rotational stability of the knee. In the setting of instability and insufficiency, reconstruction will lead to better patient outcomes for concurrent ACL/ALL injuries and postsurgical rotatory instability following ACL procedures. This innovative technique utilizes ultrasound to ascertain the precise anatomical attachments of the ALL prior to the operation. The novel nature of this ultrasound-guided reconstruction has the potential to be applicable in many other surgical procedures.

1. Suomalainen P, Järvelä T, Paakkala A, Kannus P, Järvinen M. Double-bundle versus single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized study with 5-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1511-1518.

2. Segond P. Recherches cliniques et expérimentales sur les épanchements sanguins du genou par entorse. Progrés Médical. 1879;6(6):1-85. French.

3. Caterine S, Litchfield R, Johnson M, Chronik B, Getgood A. A cadaveric study of the anterolateral ligament: re-introducing the lateral capsular ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Athrosc. 2015;23(11):3186-3195.

4. Claes S, Vereecke E, Maes M, Victor J, Verdonk P, Bellemans J. Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J Anat. 2013;223(4):321-328.

5. Dodds AL, Halewood C, Gupte CM, Williams A, Amis AA. The anterolateral ligament: Anatomy, length changes and association with the segond fracture. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(3):325-331.

6. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Anatomy and histology of the knee anterolateral ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(7):2325967113513546.

7. Kennedy MI, Claes S, Fuso FA, et al. The anterolateral ligament: An anatomic, radiographic, and biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1606-1615.

8. Helito CP, Helito PV, Bonadio MB, et al. Evaluation of the length and isometric pattern of the anterolateral ligament with serial computer tomography. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114562205.

9. Parsons EM, Gee AO, Spiekerman C, Cavanagh PR. The biomechanical function of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):669-674.

10. Zens M, Niemeyer P, Ruhhamer J, et al. Length changes of the anterolateral ligament during passive knee motion: A human cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2545-2552.

11. Helito CP, Bonadio MB, Gobbi RG, et al. Combined intra- and extra-articular reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: the reconstruction of the knee anterolateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(3):e239-e244.

12. Cianca J, John J, Pandit S, Chiou-Tan FY. Musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging of the recently described anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(2):186

13. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS, et al. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: An in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

14. Sonnery-Cottet B, Thaunat M, Freychet B, Pupim BHB, Murphy CG, Claes S. Outcome of a combined anterior cruciate ligament and anterolateral ligament reconstruction technique with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1598-1605.

15. Sonnery-Cottet B, Archbold P, Rezende FC, Neto AM, Fayard JM, Thaunat M. Arthroscopic identification of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(3):e389-e392.

16. Helito CP, Helito PV, Costa HP, et al. MRI evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee: assessment in routine 1.5-T scans. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(10):1421-1427.

17. Helito CP, Demange MK, Helito PV, et al. Evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee by means of magnetic resonance examination. Rev Bras Orthop. 2015;50(2):214-219.

18. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Radiographic landmarks for locating the femoral origin and tibial insertion of the knee anterolateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2356-2362.

Restoring native kinematics of the knee has been a primary goal of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) procedures. Double-bundle ACL reconstruction, compared to single-bundle, has been hypothesized to more effectively re-establish rotational stability by re-creating the anatomic ACL, but has not yet proven to result in better clinical outcomes.1

In 1879, Dr. Paul Segond described a “fibrous, pearly band” at the lateral aspect of the knee that avulsed off the anterolateral proximal tibia during many ACL injuries.2 The role of the lateral tissues in knee stability and their relationship with ACL pathology has attracted noteworthy attention in recent time. There have been multiple studies presenting an anatomical description of a structure at the anterolateral portion of the knee with definitive femoral, meniscal, and tibial attachments, which helps control internal rotational forces.3-7 Claes and colleagues4 later found that band of tissue to be the anterolateral ligament (ALL) and determined its injury to be pathognomonic with ACL ruptures.

The ALL is a vital static stabilizer of the tibio-femoral joint, especially during internal tibial rotation.8-10 In their report on ALL and ACL reconstruction, Helito and colleagues11 acknowledge the necessity of accurate assessment of the lateral structures through imaging to determine the presence of extra-articular injury. Musculoskeletal diagnostic ultrasound has been established as an appropriate means to identify the ALL.12

Ultrasound can accurately determine the exact anatomic location of the origin and insertion of the ALL. Reconstruction of the ALL could yield better patient outcomes for those who experience concurrent ACL/ALL injury. Here we present an innovative technique for an ultrasound-guided percutaneous method for reconstruction of the ALL and report on a patient who had underwent ALL reconstruction.

Surgical Indications

All patients undergo an ultrasound evaluation preoperatively to determine if the ALL is intact or injured. Our experience has shown that when ultrasound evaluation reveals an intact ALL, the pivot shift has never been a grade III.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, see the video that accompanies this article.

The pivot shift test is conducted under anesthesia to determine whether an ALL reconstruction is required. The patient is placed in a supine position with the knee flexed at 30o, at neutral rotation, and without any varus or valgus stress.

A No. 15 blade is used to make a small incision centered on each spinal needle. The spinal needle is replaced with a 2.4-mm drill pin (Figure 2).

The graft and FiberTape are then passed under the IT band to the distal incision. Using the length of the BioComposite SwiveLock anchor as a guide, a mark is made on the graft after tensioning the construct in line with the leg, distal to the tibial drill pin (Table 2, Figure 4).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation following an ALL procedure is similar to traditional ACL rehabilitation with an added emphasis on minimizing rotational torque of the tibia in the early stages.

Case Report

In January 2013, a 17-year-old male soccer player suffered an ACL rupture of his right knee. Later that spring, he had an ACL reconstruction with an allograft. Twelve months postoperatively, the patient returned, saying that he felt much better; however, anytime he tried to plant his foot and rotate over that fixed foot, his knee felt unstable. The physical examination revealed both negative Lachman and anterior drawer tests but a I+ pivot shift test. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination revealed an intact ACL graft. A diagnostic ultrasound evaluation revealed a distal ALL injury. After discussing the risks, benefits, and goals with the patient, we opted for a diagnostic arthroscopy and a percutaneous, ultrasound-guided reconstruction of the ALL.

Postoperatively, the patient did very well. One week after surgery, he returned, saying he felt completely stable and demonstrated by repeating the rotation of his knee. The patient continued to have no issues until he returned 13 months post-ALL surgery, complaining of a recent injury that had caused the return of his feelings of instability. An MRI evaluation showed an intact ACL graft and the possibility of a ruptured ALL. Fifteen months after the initial ALL reconstruction, we proceeded with surgery. At arthroscopy, the patient was found to have a pivot shift of I+ and an intact ACL graft. The ALL was reconstructed again using an allograft, internal brace, and bone marrow concentrate. At 13 months post-ALL reconstruction revision, the patient had no complaints.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the ALL is aimed to restore anatomic rotational kinematics. Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues14 have reported promising initial results in their 2-year follow-up study of combined ACL and ALL reconstruction outcomes. This surgical technique includes use of an internal brace, which negates the necessity for external support devices and allows for earlier mobilization of the joint. A reconstruction of the ALL, performed concurrently with the ACL, does not add recovery time, but could prevent postsurgical complications and improve rehabilitation by eliminating rotational instability that presents in some ACL-reconstructed patients.

Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues15 state that their arthroscopic identification of the ALL can help to cultivate a “less invasive and more anatomic” reconstruction. The use of musculoskeletal ultrasound allows our technique to utilize a completely noninvasive imaging tool that allows proper establishment of ALL anatomy prior to the procedure. The entirety of the ALL is easily identifiable,4,12 which has proven to be shortcoming of MRI evaluation.15-17 Accurate preoperative assessment of the lateral structures is necessary in ACL-deficient individuals.11,15 Sonography also provides a means of accurate guidance and socket creation, without generating large incisions.

If the ALL is responsible for internal rotatory stability as asserted, the structure should exhibit biomechanical properties during movement. In their study on the function of the ligament, Parsons and colleagues9 established the inverse relationship between the ALL and ACL during internal rotation. As their cadaveric knees were subjected to an internal rotatory force through increasing angles of flexion, the contribution of the ALL towards stability significantly increased while the ACL declined. Helito and colleagues8 and Zens and colleagues10 have demonstrated length changes of the ligament through varying degrees of flexion and internal rotation. Their reports indicate greater tension during knee movements, coinciding with the description of increasing ALL stability contribution by Parsons and colleagues.9 Kennedy and colleagues7 conducted a pull-to-failure test on the ALL. The average failure load was 175 N with a stiffness of 20 N/mm, illustrating the structure is a candidate for most traditional soft tissue grafts. The biomechanical evidence of the structural properties of the ALL confirms its importance in knee function and the necessity for its reconstruction.

With the understanding that ACL contributes to rotatory stability to some extent, the notion begs the question of how a centrally located ligament is able to prevent excessive rotation in a structure with a large relative radius. Biomechanically, with such a small moment arm, the ACL would experience tremendous stress when a rotatory force is applied. The same torque applied to a more superficial structure, with a greater moment, would sustain a large reduction in the applied force. The concept of a wheel and an axle should be considered. The equation is F1 × R1 = F2 × R2. We measured on a cadaveric knee the distance from the center of rotation to the ACL and the ALL, finding the radii were 5 mm and 30 mm, respectively. Taking these measurements, we would then expect the force experienced on the axle (ACL) to be 6 times greater than what would be experienced on the periphery of the wheel (ALL). The ALL (wheel) has a significant biomechanical advantage over the ACL (axle) in controlling and enduring internal rotatory forces of the knee. This would imply that if the ALL were damaged and not re-established, the ACL would experience a 6 times greater force trying to control internal rotation, which would result in a significantly increased chance of failure and rupture.

While there is a degree of dissent on the presence of the ALL, a number of studies have classified the tissue as an independent ligamentous structure.3-7 While there is disagreement on the precise location of the femoral attachment, there is a consensus on the location of the tibial and meniscal attachments. Claes and colleagues4 originally outlined the femoral attachment as anterior and distal to the origin of the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), which is the description this technique follows. Since Claes and colleagues’4 report, many have investigated the ligament’s femoral origin with delineations ranging from posterior and proximal3,5,7 to anterior and distal.6,16-18

The accurate, noninvasive nature of the musculoskeletal ultrasound prior to any incisions being made makes this technique innovative and superior to other open surgical techniques or those that require fluoroscopy.

Conclusion

The ALL has been determined to play an integral role in the rotational stability of the knee. In the setting of instability and insufficiency, reconstruction will lead to better patient outcomes for concurrent ACL/ALL injuries and postsurgical rotatory instability following ACL procedures. This innovative technique utilizes ultrasound to ascertain the precise anatomical attachments of the ALL prior to the operation. The novel nature of this ultrasound-guided reconstruction has the potential to be applicable in many other surgical procedures.

Restoring native kinematics of the knee has been a primary goal of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) procedures. Double-bundle ACL reconstruction, compared to single-bundle, has been hypothesized to more effectively re-establish rotational stability by re-creating the anatomic ACL, but has not yet proven to result in better clinical outcomes.1

In 1879, Dr. Paul Segond described a “fibrous, pearly band” at the lateral aspect of the knee that avulsed off the anterolateral proximal tibia during many ACL injuries.2 The role of the lateral tissues in knee stability and their relationship with ACL pathology has attracted noteworthy attention in recent time. There have been multiple studies presenting an anatomical description of a structure at the anterolateral portion of the knee with definitive femoral, meniscal, and tibial attachments, which helps control internal rotational forces.3-7 Claes and colleagues4 later found that band of tissue to be the anterolateral ligament (ALL) and determined its injury to be pathognomonic with ACL ruptures.

The ALL is a vital static stabilizer of the tibio-femoral joint, especially during internal tibial rotation.8-10 In their report on ALL and ACL reconstruction, Helito and colleagues11 acknowledge the necessity of accurate assessment of the lateral structures through imaging to determine the presence of extra-articular injury. Musculoskeletal diagnostic ultrasound has been established as an appropriate means to identify the ALL.12

Ultrasound can accurately determine the exact anatomic location of the origin and insertion of the ALL. Reconstruction of the ALL could yield better patient outcomes for those who experience concurrent ACL/ALL injury. Here we present an innovative technique for an ultrasound-guided percutaneous method for reconstruction of the ALL and report on a patient who had underwent ALL reconstruction.

Surgical Indications

All patients undergo an ultrasound evaluation preoperatively to determine if the ALL is intact or injured. Our experience has shown that when ultrasound evaluation reveals an intact ALL, the pivot shift has never been a grade III.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, see the video that accompanies this article.

The pivot shift test is conducted under anesthesia to determine whether an ALL reconstruction is required. The patient is placed in a supine position with the knee flexed at 30o, at neutral rotation, and without any varus or valgus stress.

A No. 15 blade is used to make a small incision centered on each spinal needle. The spinal needle is replaced with a 2.4-mm drill pin (Figure 2).

The graft and FiberTape are then passed under the IT band to the distal incision. Using the length of the BioComposite SwiveLock anchor as a guide, a mark is made on the graft after tensioning the construct in line with the leg, distal to the tibial drill pin (Table 2, Figure 4).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation following an ALL procedure is similar to traditional ACL rehabilitation with an added emphasis on minimizing rotational torque of the tibia in the early stages.

Case Report

In January 2013, a 17-year-old male soccer player suffered an ACL rupture of his right knee. Later that spring, he had an ACL reconstruction with an allograft. Twelve months postoperatively, the patient returned, saying that he felt much better; however, anytime he tried to plant his foot and rotate over that fixed foot, his knee felt unstable. The physical examination revealed both negative Lachman and anterior drawer tests but a I+ pivot shift test. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination revealed an intact ACL graft. A diagnostic ultrasound evaluation revealed a distal ALL injury. After discussing the risks, benefits, and goals with the patient, we opted for a diagnostic arthroscopy and a percutaneous, ultrasound-guided reconstruction of the ALL.

Postoperatively, the patient did very well. One week after surgery, he returned, saying he felt completely stable and demonstrated by repeating the rotation of his knee. The patient continued to have no issues until he returned 13 months post-ALL surgery, complaining of a recent injury that had caused the return of his feelings of instability. An MRI evaluation showed an intact ACL graft and the possibility of a ruptured ALL. Fifteen months after the initial ALL reconstruction, we proceeded with surgery. At arthroscopy, the patient was found to have a pivot shift of I+ and an intact ACL graft. The ALL was reconstructed again using an allograft, internal brace, and bone marrow concentrate. At 13 months post-ALL reconstruction revision, the patient had no complaints.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the ALL is aimed to restore anatomic rotational kinematics. Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues14 have reported promising initial results in their 2-year follow-up study of combined ACL and ALL reconstruction outcomes. This surgical technique includes use of an internal brace, which negates the necessity for external support devices and allows for earlier mobilization of the joint. A reconstruction of the ALL, performed concurrently with the ACL, does not add recovery time, but could prevent postsurgical complications and improve rehabilitation by eliminating rotational instability that presents in some ACL-reconstructed patients.

Sonnery-Cottet and colleagues15 state that their arthroscopic identification of the ALL can help to cultivate a “less invasive and more anatomic” reconstruction. The use of musculoskeletal ultrasound allows our technique to utilize a completely noninvasive imaging tool that allows proper establishment of ALL anatomy prior to the procedure. The entirety of the ALL is easily identifiable,4,12 which has proven to be shortcoming of MRI evaluation.15-17 Accurate preoperative assessment of the lateral structures is necessary in ACL-deficient individuals.11,15 Sonography also provides a means of accurate guidance and socket creation, without generating large incisions.

If the ALL is responsible for internal rotatory stability as asserted, the structure should exhibit biomechanical properties during movement. In their study on the function of the ligament, Parsons and colleagues9 established the inverse relationship between the ALL and ACL during internal rotation. As their cadaveric knees were subjected to an internal rotatory force through increasing angles of flexion, the contribution of the ALL towards stability significantly increased while the ACL declined. Helito and colleagues8 and Zens and colleagues10 have demonstrated length changes of the ligament through varying degrees of flexion and internal rotation. Their reports indicate greater tension during knee movements, coinciding with the description of increasing ALL stability contribution by Parsons and colleagues.9 Kennedy and colleagues7 conducted a pull-to-failure test on the ALL. The average failure load was 175 N with a stiffness of 20 N/mm, illustrating the structure is a candidate for most traditional soft tissue grafts. The biomechanical evidence of the structural properties of the ALL confirms its importance in knee function and the necessity for its reconstruction.

With the understanding that ACL contributes to rotatory stability to some extent, the notion begs the question of how a centrally located ligament is able to prevent excessive rotation in a structure with a large relative radius. Biomechanically, with such a small moment arm, the ACL would experience tremendous stress when a rotatory force is applied. The same torque applied to a more superficial structure, with a greater moment, would sustain a large reduction in the applied force. The concept of a wheel and an axle should be considered. The equation is F1 × R1 = F2 × R2. We measured on a cadaveric knee the distance from the center of rotation to the ACL and the ALL, finding the radii were 5 mm and 30 mm, respectively. Taking these measurements, we would then expect the force experienced on the axle (ACL) to be 6 times greater than what would be experienced on the periphery of the wheel (ALL). The ALL (wheel) has a significant biomechanical advantage over the ACL (axle) in controlling and enduring internal rotatory forces of the knee. This would imply that if the ALL were damaged and not re-established, the ACL would experience a 6 times greater force trying to control internal rotation, which would result in a significantly increased chance of failure and rupture.

While there is a degree of dissent on the presence of the ALL, a number of studies have classified the tissue as an independent ligamentous structure.3-7 While there is disagreement on the precise location of the femoral attachment, there is a consensus on the location of the tibial and meniscal attachments. Claes and colleagues4 originally outlined the femoral attachment as anterior and distal to the origin of the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), which is the description this technique follows. Since Claes and colleagues’4 report, many have investigated the ligament’s femoral origin with delineations ranging from posterior and proximal3,5,7 to anterior and distal.6,16-18

The accurate, noninvasive nature of the musculoskeletal ultrasound prior to any incisions being made makes this technique innovative and superior to other open surgical techniques or those that require fluoroscopy.

Conclusion

The ALL has been determined to play an integral role in the rotational stability of the knee. In the setting of instability and insufficiency, reconstruction will lead to better patient outcomes for concurrent ACL/ALL injuries and postsurgical rotatory instability following ACL procedures. This innovative technique utilizes ultrasound to ascertain the precise anatomical attachments of the ALL prior to the operation. The novel nature of this ultrasound-guided reconstruction has the potential to be applicable in many other surgical procedures.

1. Suomalainen P, Järvelä T, Paakkala A, Kannus P, Järvinen M. Double-bundle versus single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized study with 5-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1511-1518.

2. Segond P. Recherches cliniques et expérimentales sur les épanchements sanguins du genou par entorse. Progrés Médical. 1879;6(6):1-85. French.

3. Caterine S, Litchfield R, Johnson M, Chronik B, Getgood A. A cadaveric study of the anterolateral ligament: re-introducing the lateral capsular ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Athrosc. 2015;23(11):3186-3195.

4. Claes S, Vereecke E, Maes M, Victor J, Verdonk P, Bellemans J. Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J Anat. 2013;223(4):321-328.

5. Dodds AL, Halewood C, Gupte CM, Williams A, Amis AA. The anterolateral ligament: Anatomy, length changes and association with the segond fracture. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(3):325-331.

6. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Anatomy and histology of the knee anterolateral ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(7):2325967113513546.

7. Kennedy MI, Claes S, Fuso FA, et al. The anterolateral ligament: An anatomic, radiographic, and biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1606-1615.

8. Helito CP, Helito PV, Bonadio MB, et al. Evaluation of the length and isometric pattern of the anterolateral ligament with serial computer tomography. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114562205.

9. Parsons EM, Gee AO, Spiekerman C, Cavanagh PR. The biomechanical function of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):669-674.

10. Zens M, Niemeyer P, Ruhhamer J, et al. Length changes of the anterolateral ligament during passive knee motion: A human cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2545-2552.

11. Helito CP, Bonadio MB, Gobbi RG, et al. Combined intra- and extra-articular reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: the reconstruction of the knee anterolateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(3):e239-e244.

12. Cianca J, John J, Pandit S, Chiou-Tan FY. Musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging of the recently described anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(2):186

13. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS, et al. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: An in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

14. Sonnery-Cottet B, Thaunat M, Freychet B, Pupim BHB, Murphy CG, Claes S. Outcome of a combined anterior cruciate ligament and anterolateral ligament reconstruction technique with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1598-1605.

15. Sonnery-Cottet B, Archbold P, Rezende FC, Neto AM, Fayard JM, Thaunat M. Arthroscopic identification of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(3):e389-e392.

16. Helito CP, Helito PV, Costa HP, et al. MRI evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee: assessment in routine 1.5-T scans. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(10):1421-1427.

17. Helito CP, Demange MK, Helito PV, et al. Evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee by means of magnetic resonance examination. Rev Bras Orthop. 2015;50(2):214-219.

18. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Radiographic landmarks for locating the femoral origin and tibial insertion of the knee anterolateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2356-2362.

1. Suomalainen P, Järvelä T, Paakkala A, Kannus P, Järvinen M. Double-bundle versus single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized study with 5-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1511-1518.

2. Segond P. Recherches cliniques et expérimentales sur les épanchements sanguins du genou par entorse. Progrés Médical. 1879;6(6):1-85. French.

3. Caterine S, Litchfield R, Johnson M, Chronik B, Getgood A. A cadaveric study of the anterolateral ligament: re-introducing the lateral capsular ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Athrosc. 2015;23(11):3186-3195.

4. Claes S, Vereecke E, Maes M, Victor J, Verdonk P, Bellemans J. Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J Anat. 2013;223(4):321-328.

5. Dodds AL, Halewood C, Gupte CM, Williams A, Amis AA. The anterolateral ligament: Anatomy, length changes and association with the segond fracture. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(3):325-331.

6. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Anatomy and histology of the knee anterolateral ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(7):2325967113513546.

7. Kennedy MI, Claes S, Fuso FA, et al. The anterolateral ligament: An anatomic, radiographic, and biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1606-1615.

8. Helito CP, Helito PV, Bonadio MB, et al. Evaluation of the length and isometric pattern of the anterolateral ligament with serial computer tomography. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(12):2325967114562205.

9. Parsons EM, Gee AO, Spiekerman C, Cavanagh PR. The biomechanical function of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):669-674.

10. Zens M, Niemeyer P, Ruhhamer J, et al. Length changes of the anterolateral ligament during passive knee motion: A human cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2545-2552.

11. Helito CP, Bonadio MB, Gobbi RG, et al. Combined intra- and extra-articular reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: the reconstruction of the knee anterolateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(3):e239-e244.

12. Cianca J, John J, Pandit S, Chiou-Tan FY. Musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging of the recently described anterolateral ligament of the knee. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(2):186

13. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS, et al. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: An in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

14. Sonnery-Cottet B, Thaunat M, Freychet B, Pupim BHB, Murphy CG, Claes S. Outcome of a combined anterior cruciate ligament and anterolateral ligament reconstruction technique with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1598-1605.

15. Sonnery-Cottet B, Archbold P, Rezende FC, Neto AM, Fayard JM, Thaunat M. Arthroscopic identification of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(3):e389-e392.

16. Helito CP, Helito PV, Costa HP, et al. MRI evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee: assessment in routine 1.5-T scans. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(10):1421-1427.

17. Helito CP, Demange MK, Helito PV, et al. Evaluation of the anterolateral ligament of the knee by means of magnetic resonance examination. Rev Bras Orthop. 2015;50(2):214-219.

18. Helito CP, Demange MK, Bonadio MB, et al. Radiographic landmarks for locating the femoral origin and tibial insertion of the knee anterolateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2356-2362.

Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Reconstruction of the Anterolateral Ligament: Surgical Technique

In My Athletic Trainer’s Bag

Editor’s Note: Doug Quon, MAT, ATC, PES, is the Assistant Athletic Trainer for the Washington Redskins. Click the PDF button below to view and download his list of the essential components of an athletic trainer’s bag for high school football

Editor’s Note: Doug Quon, MAT, ATC, PES, is the Assistant Athletic Trainer for the Washington Redskins. Click the PDF button below to view and download his list of the essential components of an athletic trainer’s bag for high school football

Editor’s Note: Doug Quon, MAT, ATC, PES, is the Assistant Athletic Trainer for the Washington Redskins. Click the PDF button below to view and download his list of the essential components of an athletic trainer’s bag for high school football

Exertional Heat Stroke and American Football: What the Team Physician Needs to Know

Football, one of the most popular sports in the United States, is additionally recognized as a leading contributor to sports injury secondary to the contact collision nature of the endeavor. There are an estimated 1.1 million high school football players with another 100,000 participants combined in the National Football League (NFL), college, junior college, Arena Football League, and semipro levels of play.1 USA Football estimates that an additional 3 million youth participate in community football leagues.1 The National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research recently calculated a fatality rate of 0.14 per 100,000 participants in 2014 for the 4.2 million who play football at all levels—and 0.45 per 100,000 in high school.1 While direct deaths from head and spine injury remain a significant contributor to the number of catastrophic injuries, indirect deaths (systemic failure) predominate. Exertional heat stroke (EHS) has emerged as one of the leading indirect causes of death in high school and collegiate football. Boden and colleagues2 reported that high school and college football players sustain approximately 12 fatalities annually, with indirect systemic causes being twice as common as direct blunt trauma.2The most common indirect causes identified included cardiac failure, heat illness, and complications of sickle cell trait (SCT). It was also noted that the risk of SCT, heat-related, and cardiac deaths increased during the second decade of the study, indicating these conditions may require a greater emphasis on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. This review details for the team physician the unique challenge of exercising in the heat to the football player, and the prevention, diagnosis, management and return-to-play issues pertinent to exertional heat illness (EHI).

The Challenge

EHS represents the most severe manifestation of EHI—a gamut of diseases commonly encountered during the hot summer months when American football season begins. The breadth of EHI includes several important clinical diagnoses: exercise-associated muscle cramps (heat cramps); heat exhaustion with and without syncope; heat injury with evidence of end organ injury (eg, rhabdomyolysis); and EHS. EHS is defined as “a form of hyperthermia associated with a systemic inflammatory response leading to a syndrome of multi-organ dysfunction in which encephalopathy predominates.”3 EHS, if left untreated, or even if clinical treatment is delayed, may result in significant end organ morbidity and/or mortality.

During exercise, the human thermoregulatory system mitigates heat gain by increasing skin blood flow and sweating, causing an increased dissipation of heat to the surrounding environment by leveraging conduction, convection, and evaporation.4,5 Elevated environmental temperatures, increased humidity, and dehydration can impede the body’s ability to dissipate heat at a rate needed to maintain thermoregulation. This imbalance can result in hyperthermia secondary to uncompensated heat stress,5 which in turn can lead to EHI. Football players have unique challenges that make them particularly vulnerable to EHI. The summer heat during early-season participation and the requirement for equipment that covers nearly 60% of body surfaces pose increased risk of volume losses and hyperthermia that trigger the onset of EHI.6 Football athletes’ body compositions and physical size are additional contributing risk factors; the relatively high muscle and fat content increase thermogenicity, which require their bodies to dissipate more heat.7

An estimated 9000 cases of EHI occur annually across all high school sports,8 with an incidence of 1.6:100,000 athlete-exposures.8,9 Studies have demonstrated, however, that EHI occurs in football 11.4 times more often than in all other high school sports combined.10 The incidence of nonfatal EHI in all levels of football is 4.42-5:100,000.8,9 Between 2000 and 2014, 41 football players died from EHS.1 In football, approximately 75% of all EHI events occurred during practices, while only 25% of incidents occurred during games.8

Given these potentially deadly consequences, it is important that football team physicians are not only alert to the early symptoms of heat illness and prepared to intervene to prevent the progression to EHS, but are critical leaders in educating coaches and players in evidence-based EHI prevention practices and policies.

Prevention

EHS is a preventable condition, arguably the most common cause of preventable nontraumatic exertional death in young athletes in the United States. Close attention to mitigating risk factors should begin prior to the onset of preseason practice and continue through the early season, where athletes are at the highest risk of developing heat illness.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention is fundamental to minimizing the occurrences of EHI. It focuses on the following methods: recognition of inherent risk factors, acclimatization, hydration, and avoidance of inciting substances (including supplements).

Pre-Participation Examination. The purpose of the pre-participation examination (PPE) is to maximize an athlete’s safety by identifying medical conditions that place the athlete at risk.11,12 The Preparticipation Physical Evaluation, 4th edition, the most widely used consensus publication, specifically queries if an athlete has a previous history of heat injury. However, it only indirectly addresses intrinsic risk factors that may predispose an athlete to EHI who has never had an EHI before. Therefore, providers should take the opportunity of the PPE to inquire about additional risk factors that may make an athlete high risk for sustaining a heat injury. Common risk factors for EHI are listed in Table 1.

Heat Acclimatization. The risk of EHI escalates significantly when athletes are subjected to multiple stressors during periods of heat exposure, such as sudden increases in intensity or duration of exercise; prolonged new exposures to heat; dehydration; and sleep loss.5 When football season begins in late summer, athletes are least conditioned as temperatures reach their seasonal peak, causing increased risk of EHI.15 Planning for heat acclimatization is vital for all athletes who exercise in hot environments. Acclimatization procedures place progressively mounting physiologic strains on the body to improve athletes’ ability to dissipate heat, diminishing thermoregulatory and cardiovascular exertion.4,5 Acclimatization begins with expansion of plasma volume on days 3 to 6, causing improvements in cardiac efficiency and resulting in an overall decrease in basal internal body temperature.4,5,15 This process results in improvements in heat tolerance and exercise performance, evolving over 10 to 14 days of gradual escalation of exercise intensity and duration.5,10,11,16 However, poor fitness levels and extreme temperatures can prolong this period, requiring up to 2 to 3 months to fully take effect.5,7

The National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) have released consensus guidelines regarding heat acclimatization protocols for football athletes at the high school and college levels (Tables 3 and 4). Each of these guidelines involves an initial period without use of protective equipment, followed by a gradual addition of further equipment.11,16

Secondary Prevention

Despite physicians’ best efforts to prevent all cases of EHI, athletes will still experience the effects of exercise-induced hyperthermia. The goal of secondary prevention is to slow the progression of this hyperthermia so that it does not progress to more dangerous EHI.

Hydration. Dehydration is an important risk factor for EHI. Sweat maintains thermoregulation by dissipating heat generated during exercise; however, it also contributes to body water losses. Furthermore, intravascular depletion decreases stroke volume, thereby increasing cardiovascular strain. It is estimated that for every 1% loss in body mass from dehydration, body temperature rises 0.22°C in comparison to a euhydrated state.6 Dehydration occurs more rapidly in hot environments, as fluid is lost through increased sweat production.7 After approximately 6% to 10% body weight volume loss, cardiac output cannot be maintained, diminishing sweat production and blood flow to both skin and muscle and causing diminished performance and a significant risk of heat exhaustion.7 If left unchecked, these physiologic changes result in further elevations in body temperature and increased cardiovascular strain, ultimately placing the athlete at significant risk for development of EHS.

Adequate hydration to maintain euvolemia is an important step in avoiding possible EHI. Multiple studies have shown that football players experience a baseline hypovolemia during their competition season,6 a deficit that is most marked during the first week of practices.17 This deficit is multifactorial, as football players expend a significant amount of fluid through sweat, are not able to adequately replace these losses during practice, and do not appropriately hydrate off the field.6,18 Some players, especially linemen, sweat at a higher rate than their teammates, posing a possible risk of significant dehydration.6 Coaches and players alike should be educated on the importance of adequate hydration to meet their fluid needs.

The goal of hydration during exercise is to prevent large fluid losses that can adversely affect performance and increase risk of EHI;6 it may be unrealistic to replace all fluid losses during the practice period. Instead, athletes should target complete volume replacement over the post-exercise period.6 Some recommend hydrating based upon thirst drive; however, thirst is activated following a volume loss of approximately 2% body mass, the same degree of losses that place athletes at an increased risk for performance impairment and EHI.4,6,11,12 Individuals should have access to fluids throughout practice and competition and be encouraged to hydrate as needed.6,12,15 Furthermore, staff should modify their practices based upon WBGT and acclimatization status to provide more frequent hydration breaks.

Hyperhydration and Salt Intake. Of note, there are inherent risks to hyperhydration. Athletes with low sweat rates have an increased risk of overhydration and the development of exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH),6 a condition whose presentation is very similar to EHS. In addition, inadequate sodium intake and excessive sweating can also contribute to the development of EAH. EAH has been implicated in the deaths of 2 football players in 2014.1,6 Establishing team hydration guidelines and educating players and staff on appropriate hydration and dietary salt intake is essential to reduce the risk of both dehydration and hyperhydration and their complications.6Intra-Event Cooling. During exercise, team physicians can employ strategies for cooling athletes during exertion to mitigate their risk of EHI by decreasing thermal and cardiovascular strain.4,19 Cooling during exercise is hypothesized to allow for accelerated heat dissipation, where heat is lost from the body more effectively. This accelerated loss enables athletes to maintain a higher heat storage capacity over the duration of exercise, avoiding uncompensated heat stresses that ultimately cause EHI.19

Some intra-event cooling strategies include the use of cooling garments, cooling packs, and cold water/slurry ingestion. Cooling garments lower skin temperature, which in turn can decrease thermoregulatory strains;4 a recent meta-analysis of intra-event cooling modalities revealed that wearing an ice vest during exercise resulted in the greatest decrease in thermal heat strain.19 Internal cooling strategies—namely ingestion of cold fluids/ice slurry—have shown some mild benefit in decreasing internal temperatures; however, some studies have demonstrated some decrease in sweat production associated with cold oral intake used in isolation.19 Overall, studies have shown that combining external (cooling clothing, ice packs, fanning) and internal (cold water, ice slurry) cooling methods result in a greater cooling effect than a use of a single method.4

Tertiary Prevention

The goal of tertiary prevention is to mitigate the risk of long-term adverse outcomes following an EHS event. The most effective means of reducing risk for morbidity and mortality is rapid identification and treatment of EHS as well as close evaluation of an athlete’s return to activity in heat. This process is spearheaded by an effective and well-rehearsed emergency action plan.

Diagnosis and Management

Rapid identification and treatment of EHS is crucial to minimizing the risk of poor outcomes.7 Any delay in the treatment of EHS can dramatically increase the likelihood of associated morbidity and mortality.20

EHS is diagnosed by an elevated rectal temperature ≥40°C (104°F) and associated central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction.21 EHS should be strongly suspected in any athlete exercising in heat who exhibits signs of CNS dysfunction, including disorientation, confusion, dizziness, erratic behavior, irritability, headache, loss of coordination, delirium, collapse, or seizures.7,12,15 EHS may also present with symptoms of heat exhaustion, including fatigue, hyperventilation, tachycardia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hypotension.7,12,15

Rectal temperature should be taken for any athlete with suspected EHS, as other modalities—oral, skin, axillary, and aural—can be inaccurate and easily modified by ambient confounders such as ambient and skin temperature, athlete hyperventilation, and consumption of liquids.7,11,12 Athletes exhibiting CNS symptoms with moderately elevated rectal temperatures that do not exceed 40°C should also be assumed to be suffering from EHS and treated with rapid cooling.11 On the other hand, athletes with CNS symptoms who are normothermic should be assumed to have EAH until ruled out by electrolyte assessment; IV fluids should be at no more than keep vein open (KVO) pending this determination.11 In some cases, an athlete may initially present with altered mental status but return to “normal.” However, this improvement may represent a “lucid period”; evaluation should continue with rectal temperature and treatment, as EHS in these cases may progress quickly.15

Treatment is centered on rapid, whole body cooling initiated at the first sign of heat illness.7,22 The goal of treatment is to achieve a rectal temperature <38.9°C within 30 minutes of the onset of EHS.15 Upon diagnosis, the athlete should be quickly placed in a tub of ice water to facilitate cold water immersion (CWI) therapy. Some guidelines suggest the athlete’s clothing be removed to potentiate evaporative cooling during CWI;12 however, cooling should not be delayed due to difficulties in removing equipment. CWI, where a heat stroke victim is submerged in ice water up to their neck while water is continuously circulated, is generally considered to be the gold standard treatment as it is the modality with the highest recorded cooling rates and the lowest rate of morbidity and mortality.7,20,21 Multiple studies of CWI have shown that survival nears 100% when aggressive cooling starts within 5 minutes of collapse or identification of EHS.20,21,22

If whole body CWI is unavailable, alternative methods of rapid cooling should be employed. Partial CWI, with torso immersion being preferable to the extremities, has been shown to achieve an acceptable rate of cooling to achieve sufficient drops in internal body temperature.20,23 However, one popular treatment—applying ice packs to the whole body, in particular to the groin and axillae—has not been shown to be sufficient to achieve standard cooling goals.20 None of these methods have been shown to be as effective as CWI.23

Intravenous access should be initiated with fluid resuscitation dictated by the provider’s assessment. Normal saline is recommended as the resuscitative fluid of choice, with the rate dictated by clinical judgment and adjusted as guided by electrolyte determination and clinical response. It cannot be overstated that in normothermic patients with confusion, EAH is the diagnosis of exclusion and aggressive fluid resuscitation should be withheld until electrolyte determination.

Once rectal temperature descends appropriately (~38.9°C), the cooling process should stop and the individual should be transported to a hospital for further observation20 and evaluation of possible sequelae, including rhabdomyolysis and renal injury, cardiac dysfunction and arrhythmia, severe electrolyte abnormalities, acute respiratory distress syndrome, lactic acidosis, and other forms of end-organ failure (Figure).

Rapid cooling is more crucial than transport; transport poses a risk of delayed cooling, which can dramatically increase an individual’s risk of morbidity and mortality.20,23 In situations where a patient can be cooled on-site, physicians should pursue cooling before transporting the patient to a medical treatment facility.

Emergency Action Plan

Team physicians should be proactive in developing an emergency action plan to address possible EHS events. These plans should be site-specific, addressing procedures for all practice and home competition locations.12 All competition venues should have a CWI tub on-site in events where there is an increased risk of EHS.12,15,20 This tub should be set up and functional for all high-risk activities, including practices.12

Following recognition of a potential case of EHS, treatment teams should have procedures in place to transport athletes to the treatment area, obtain rectal temperature, initiate rapid cooling, and stabilize the athlete for transport to an emergency department (ED) for further evaluation.12,15 A written record of treatments and medications provided during athlete stabilization should be maintained and transported with the athlete to the ED.15 A list of helpful equipment and supplies for treatment of EHS can be found in Table 5.

EHS is a unique life-threatening situation where it is best to treat the patient on the sideline before transport.15 Those athletes transported before cooling risk spending an increased amount of time above critical temperatures for cell damage, which has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality. This mantra of “cool first, transport second” cannot be overemphasized, as those individuals with EHS who present to the ED with a persisting rectal temperature >41°F may risk up to an 80% mortality rate.24 Conversely, a recent large, retrospective study of 274 EHS events sustained during the Falmouth Road Race found a 100% survival rate when athletes were rapidly identified via rectal thermometry and treated with aggressive, rapid cooling through CWI.21

Return to Play

Perhaps the most challenging and important role the team physician has is determining an athlete’s return to play following EHI, as there currently are no evidence-based guidelines for return to activity for these athletes.7 The decisions surrounding return to play are highly individualized, as recovery from EHS and heat injury is associated with the duration of internal body temperature elevation above the critical level (40°C).7,20 Guidelines for return to activity following recovery from EHI differ among experts and institutions.7,25 The general consensus from these guidelines is that, at minimum, athletes should not participate in any physical activity until they are asymptomatic and all blood tests have normalized.11 Following this asymptomatic period, most guidelines advocate for a slow, deliberate return to activity.11 The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) offers one reasonable approach to the returning athlete following EHS:7

- No exercise for at least 7 days following release from medical care.

- Follow-up with a physician 1 week after release from medical care for physical examination and any warranted lab or radiologic studies (based upon organ systems affected during EHS).

- Once cleared to return to activity, the athlete begins exercise in a cool environment, gradually increasing the duration, intensity, and heat exposure over 2 weeks to demonstrate heat tolerance and acclimatization.

- Athletes who cannot resume vigorous activity due to recurrent symptoms (eg, excessive fatigue) should be reevaluated after 4 weeks. Laboratory exercise-heat tolerance testing may be useful in this setting.

- The athlete may resume full competition once they are able to participate in full training in the heat for 2 to 4 weeks without adverse effects.

Heat tolerance testing (HTT) in these athletes remains controversial.5 26 The ACSM recommends that HTT be considered only for those unable to return to vigorous activity after a suitable period (approximately 4 weeks). In contrast, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) uses HTT to evaluate soldiers following EHS to guide decision-making about return to duty.27 The IDF HTT assumes that individuals will respond differently to heat stresses. They identify individuals who are “heat intolerant” as being unable to tolerate specific heat challenges, indicated by increases in body temperature occurring more rapidly than normal responders under identical environmental and exercise conditions. However, despite being used for more than 30 years, there is no clear evidence that HTT adequately predicts who will experience subsequent episodes of EHS.

Conclusion

While the recognized cornerstone of being a team physician is the provision of medical care, the ACSM Team Physician Consensus Statement28 further delineates the medical and administrative responsibilities as both (1) understanding medical management and prevention of injury and illness in athletes; and (2) awareness of or involvement in the development and rehearsal of an emergency action plan. These tenets are critical for the team physician who accepts the responsibility to cover sports at the high school level or higher. Football team physicians play an essential role in mitigating risk of EHI in their athletes. Through development and execution of both comprehensive prevention strategies and emergency action plans, physicians can work to minimize athletes’ risk of both developing and experiencing significant adverse outcomes from an EHI.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):340-348. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Kucera KL, Klossner D, Colgate B, Cantu RC. Annual Survey of Football Injury Research: 1931-2014. National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research Web site. https://nccsir.unc.edu/files/2013/10/Annual-Football-2014-Fatalities-Final.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2016.

2. Boden BP, Breit I, Beachler JA, Williams A, Mueller FO. Fatalities in high school and college football players. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1108-1116.

3. Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(25):1978-1988.

4. Racinais S, Alonso JM, Coutts AJ, et al. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25 Suppl 1:6-19.

5. Pryor RR, Casa DJ, Adams WM, et al. Maximizing athletic performance in the heat. Strength Cond J. 2013;35(6):24-33.

6. Adams WM, Casa DJ. Hydration for football athletes. Sports Sci Exchange. 2015;28(141):1-5.

7. American College of Sports Medicine, Armstrong LE, Casa DJ, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exertional heat illness during training and competition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(3):556-572.

8. Yard EE, Gilchrist J, Haileyesus T, et al. Heat illness among high school athletes--United States, 2005-2009. J Safety Res. 2010;41(6):471-474.

9. Huffman EA, Yard EE, Fields SK, Collins CL, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of rare injuries and conditions among United States high school athletes during the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 school years. J Athl Train. 2008;43(6):624-630.

10. Kerr ZY, Casa DJ, Marshall SW, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of exertional heat illness among U.S. high school athletes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1):8-14.

11. Casa DJ, DeMartini JK, Bergeron MF, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: exertional heat illnesses. J Athl Train. 2015;50(9):986-1000.

12. Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA. The inter-association task force for preventing sudden death in secondary school athletics programs: best-practices recommendations. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):546-553.

13. Gardner JW, Kark JA, Karnei K, et al. Risk factors predicting exertional heat illness in male Marine Corps recruits. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(8):939-944.

14. Gundstein AJ, Ramseyer C, Zhao F, et al. A retrospective analysis of American football hyperthermia deaths in the United States. Int J Biometerol. 2012;56(1):11-20.

15. Armstrong LE, Johnson EC, Casa DJ, et al. The American football uniform: uncompensable heat stress and hyperthermic exhaustion. J Athl Train. 2010;45(2):117-127.

16. Casa DJ, Csillan D; Inter-Association Task Force for Preseason Secondary School Athletics Participants, et al. Preseason heat-acclimatization guidelines for secondary school athletics. J Athl Train. 2009;44(3):332-333.

17. Godek SF, Godek JJ, Bartolozzi AR. Hydration status in college football players during consecutive days of twice-a-day preseason practices. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(6):843-851.

18. Stover EA, Zachwieja J, Stofan J, Murray R, Horswill CA. Consistently high urine specific gravity in adolescent American football players and the impact of an acute drinking strategy. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27(4):330-335.

19. Bongers CC, Thijssen DH, Veltmeijer MTW, Hopman MT, Eijsvogels TM. Precooling and percooling (cooling during exercise) both improve performance in the heat: a meta-analytical review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(6):377-384.

20. Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Lee EC, Yeargin SW, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Cold water immersion: the gold standard for exertional heatstroke treatment. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35(3):141-149.

21. DeMartini JK, Casa DJ, Stearns R, et al. Effectiveness of cold water immersion in the treatment of exertional heat stroke at the Falmouth Road Race. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(2):240-245.

22. Casa DJ, Kenny GP, Taylor NA. Immersion treatment for exertional hyperthermia: cold or temperate water? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1246-1252.

23. Casa DJ, Armstrong LE, Kenny GP, O’Connor FG, Huggins RA. Exertional heat stroke: new concepts regarding cause and care. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(3):115-122.

24. Argaud L, Ferry T, Le QH, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of heat stroke following the 2003 heat wave in Lyon, France. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(20):2177-2183.

25. O’Connor FG, Casa DJ, Bergeron MF, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable on exertional heat stroke--return to duty/return to play: conference proceedings. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(5):314-321.

26. Kazman JB, Heled Y, Lisman PJ, Druyan A, Deuster PA, O’Connor FG. Exertional heat illness: the role of heat tolerance testing. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(2):101-105.

27. Moran DS, Heled Y, Still L, Laor A, Shapiro Y. Assessment of heat tolerance for post exertional heat stroke individuals. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(6):CR252-CR257.

28. Herring SA, Kibler WB, Putukian M. Team Physician Consensus Statement: 2013 update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(8):1618-1622.

29. Heat stroke treatment. Korey Stringer Institute University of Connecticut Web site. http://ksi.uconn.edu/emergency-conditions/heat-illnesses/exertional-heat-stroke/heat-stroke-treatment/. Accessed June 14, 2016.

30. Headquarters, Department of the Army and the Air Force. Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management. Technical Bulletin Medical 507. http://www.dir.ca.gov/oshsb/documents/Heat_illness_prevention_tbmed507.pdf. Published March 7, 2003. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Football, one of the most popular sports in the United States, is additionally recognized as a leading contributor to sports injury secondary to the contact collision nature of the endeavor. There are an estimated 1.1 million high school football players with another 100,000 participants combined in the National Football League (NFL), college, junior college, Arena Football League, and semipro levels of play.1 USA Football estimates that an additional 3 million youth participate in community football leagues.1 The National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research recently calculated a fatality rate of 0.14 per 100,000 participants in 2014 for the 4.2 million who play football at all levels—and 0.45 per 100,000 in high school.1 While direct deaths from head and spine injury remain a significant contributor to the number of catastrophic injuries, indirect deaths (systemic failure) predominate. Exertional heat stroke (EHS) has emerged as one of the leading indirect causes of death in high school and collegiate football. Boden and colleagues2 reported that high school and college football players sustain approximately 12 fatalities annually, with indirect systemic causes being twice as common as direct blunt trauma.2The most common indirect causes identified included cardiac failure, heat illness, and complications of sickle cell trait (SCT). It was also noted that the risk of SCT, heat-related, and cardiac deaths increased during the second decade of the study, indicating these conditions may require a greater emphasis on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. This review details for the team physician the unique challenge of exercising in the heat to the football player, and the prevention, diagnosis, management and return-to-play issues pertinent to exertional heat illness (EHI).

The Challenge

EHS represents the most severe manifestation of EHI—a gamut of diseases commonly encountered during the hot summer months when American football season begins. The breadth of EHI includes several important clinical diagnoses: exercise-associated muscle cramps (heat cramps); heat exhaustion with and without syncope; heat injury with evidence of end organ injury (eg, rhabdomyolysis); and EHS. EHS is defined as “a form of hyperthermia associated with a systemic inflammatory response leading to a syndrome of multi-organ dysfunction in which encephalopathy predominates.”3 EHS, if left untreated, or even if clinical treatment is delayed, may result in significant end organ morbidity and/or mortality.

During exercise, the human thermoregulatory system mitigates heat gain by increasing skin blood flow and sweating, causing an increased dissipation of heat to the surrounding environment by leveraging conduction, convection, and evaporation.4,5 Elevated environmental temperatures, increased humidity, and dehydration can impede the body’s ability to dissipate heat at a rate needed to maintain thermoregulation. This imbalance can result in hyperthermia secondary to uncompensated heat stress,5 which in turn can lead to EHI. Football players have unique challenges that make them particularly vulnerable to EHI. The summer heat during early-season participation and the requirement for equipment that covers nearly 60% of body surfaces pose increased risk of volume losses and hyperthermia that trigger the onset of EHI.6 Football athletes’ body compositions and physical size are additional contributing risk factors; the relatively high muscle and fat content increase thermogenicity, which require their bodies to dissipate more heat.7

An estimated 9000 cases of EHI occur annually across all high school sports,8 with an incidence of 1.6:100,000 athlete-exposures.8,9 Studies have demonstrated, however, that EHI occurs in football 11.4 times more often than in all other high school sports combined.10 The incidence of nonfatal EHI in all levels of football is 4.42-5:100,000.8,9 Between 2000 and 2014, 41 football players died from EHS.1 In football, approximately 75% of all EHI events occurred during practices, while only 25% of incidents occurred during games.8

Given these potentially deadly consequences, it is important that football team physicians are not only alert to the early symptoms of heat illness and prepared to intervene to prevent the progression to EHS, but are critical leaders in educating coaches and players in evidence-based EHI prevention practices and policies.

Prevention

EHS is a preventable condition, arguably the most common cause of preventable nontraumatic exertional death in young athletes in the United States. Close attention to mitigating risk factors should begin prior to the onset of preseason practice and continue through the early season, where athletes are at the highest risk of developing heat illness.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention is fundamental to minimizing the occurrences of EHI. It focuses on the following methods: recognition of inherent risk factors, acclimatization, hydration, and avoidance of inciting substances (including supplements).

Pre-Participation Examination. The purpose of the pre-participation examination (PPE) is to maximize an athlete’s safety by identifying medical conditions that place the athlete at risk.11,12 The Preparticipation Physical Evaluation, 4th edition, the most widely used consensus publication, specifically queries if an athlete has a previous history of heat injury. However, it only indirectly addresses intrinsic risk factors that may predispose an athlete to EHI who has never had an EHI before. Therefore, providers should take the opportunity of the PPE to inquire about additional risk factors that may make an athlete high risk for sustaining a heat injury. Common risk factors for EHI are listed in Table 1.

Heat Acclimatization. The risk of EHI escalates significantly when athletes are subjected to multiple stressors during periods of heat exposure, such as sudden increases in intensity or duration of exercise; prolonged new exposures to heat; dehydration; and sleep loss.5 When football season begins in late summer, athletes are least conditioned as temperatures reach their seasonal peak, causing increased risk of EHI.15 Planning for heat acclimatization is vital for all athletes who exercise in hot environments. Acclimatization procedures place progressively mounting physiologic strains on the body to improve athletes’ ability to dissipate heat, diminishing thermoregulatory and cardiovascular exertion.4,5 Acclimatization begins with expansion of plasma volume on days 3 to 6, causing improvements in cardiac efficiency and resulting in an overall decrease in basal internal body temperature.4,5,15 This process results in improvements in heat tolerance and exercise performance, evolving over 10 to 14 days of gradual escalation of exercise intensity and duration.5,10,11,16 However, poor fitness levels and extreme temperatures can prolong this period, requiring up to 2 to 3 months to fully take effect.5,7

The National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) have released consensus guidelines regarding heat acclimatization protocols for football athletes at the high school and college levels (Tables 3 and 4). Each of these guidelines involves an initial period without use of protective equipment, followed by a gradual addition of further equipment.11,16

Secondary Prevention

Despite physicians’ best efforts to prevent all cases of EHI, athletes will still experience the effects of exercise-induced hyperthermia. The goal of secondary prevention is to slow the progression of this hyperthermia so that it does not progress to more dangerous EHI.

Hydration. Dehydration is an important risk factor for EHI. Sweat maintains thermoregulation by dissipating heat generated during exercise; however, it also contributes to body water losses. Furthermore, intravascular depletion decreases stroke volume, thereby increasing cardiovascular strain. It is estimated that for every 1% loss in body mass from dehydration, body temperature rises 0.22°C in comparison to a euhydrated state.6 Dehydration occurs more rapidly in hot environments, as fluid is lost through increased sweat production.7 After approximately 6% to 10% body weight volume loss, cardiac output cannot be maintained, diminishing sweat production and blood flow to both skin and muscle and causing diminished performance and a significant risk of heat exhaustion.7 If left unchecked, these physiologic changes result in further elevations in body temperature and increased cardiovascular strain, ultimately placing the athlete at significant risk for development of EHS.

Adequate hydration to maintain euvolemia is an important step in avoiding possible EHI. Multiple studies have shown that football players experience a baseline hypovolemia during their competition season,6 a deficit that is most marked during the first week of practices.17 This deficit is multifactorial, as football players expend a significant amount of fluid through sweat, are not able to adequately replace these losses during practice, and do not appropriately hydrate off the field.6,18 Some players, especially linemen, sweat at a higher rate than their teammates, posing a possible risk of significant dehydration.6 Coaches and players alike should be educated on the importance of adequate hydration to meet their fluid needs.