User login

Identifying Observation Stays in Medicare Data: Policy Implications of a Definition

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

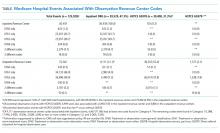

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine