User login

The diagnosis and surgical repair of vesicovaginal fistula

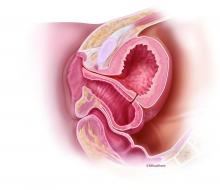

Vesicovaginal fistulas (VVFs) are the most common type of urogenital fistulas – approximately three times more common than ureterovaginal fistulas – and can be a debilitating problem for women.

Most of the research published in recent years on VVFs and other urogenital fistulas comes from developing countries where these abnormal communications are a common complication of obstructed labor. In the United States, despite a relative paucity of data, VVFs are known to occur most often as a sequelae of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. Estimates of the incidence of VVF and other urogenital fistula formation are debated but have ranged from 0.5% or less after simple hysterectomy to as high as 2% after radical hysterectomy. Most VVFs are believed to occur after hysterectomy performed for benign disease, and many – but not all – are caused by inadvertent bladder injury that was not recognized intraoperatively.

Women who have had one or more cesarean deliveries and those who have had prior pelvic or vaginal surgery are at increased risk. In addition, both radiation therapy and inflammation that occur with diseases such as pelvic inflammatory disease or inflammatory bowel disease can negatively affect tissue quality and healing from surgical procedures – and can lead ultimately to the development of urogenital fistulas – although even less is known about incidence in these cases.

Prevention

Intraoperatively, VVFs may best be prevented through careful mobilization of the bladder off the vaginal wall, the use of delayed absorbable sutures (preferably Vicryl sutures), and the use of cystoscopy to assess the bladder for injury. If cystoscopy is not available, retrograde filling with a Foley catheter will still be helpful.

An overly aggressive approach to creating the bladder flap during hysterectomy and other surgeries can increase the risk of devascularization and the subsequent formation of fistulas. When the blood supply is found to have been compromised, affected tissue can be strengthened by oversewing with imbrication. When an inadvertent cystotomy is identified, repair is often best achieved with omental tissue interposed between the bladder and vagina. If there is any doubt about bladder integrity, an interposition graft between the bladder flap and the vaginal cuff will help reduce the incidence of fistula formation. Whenever overlapping suture lines occur (the vaginal cuff and the cystotomy repair), the risk of VVF formation will increase. Other than that using omentum, peritoneal grafts will also work well.

VVF formation may still occur, however, despite recognition and repair of an injury – and despite normal findings on cystoscopy. In patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other prior pelvic surgery, for example, tissue devascularization may cause a delayed injury, with the process of tissue necrosis and VVF formation occurring up to a month after surgery. It is important to appreciate the factors that predispose patients to VVF and to anticipate an increased risk, but in many cases of delayed VVF, it’s quite possible that nothing could have been done to prevent the problem.

Work-up

Vesicovaginal fistulas typically present as painless, continuous urine leakage from the vagina. The medical history should include standard questions about pelvic health history and symptom characteristics (in order to exclude hematuria or leakage of fluid other than urine), as well as questions aimed at differentiating symptoms of VVF from other causes of urinary incontinence, such as stress incontinence. In my experience, urine leakage is often incorrectly dismissed as stress incontinence when it is actually VVF. A high index of suspicion will help make an earlier diagnosis. This does not usually change the management, but helps manage the anxiety, expectations, and needs of the patient.

I recommend beginning the work-up for a suspected VVF with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder for injury. An irregular appearance of the bladder, signs of inflammation, and poor or absent ureteral efflux are often indicative of VVF in the presence of vaginal leakage. Following cystoscopy, I perform a split speculum examination of the vagina. Most injuries will be on the anterior wall or the apex (cuff). A recently formed fistula may appear as a hole or as a small, red area of granulation tissue with no visible opening.

It can be difficult to visualize the vaginal fistula opening of more mature fistulas; similarly, very small fistulas may be difficult to find because of their size and the anatomy of the vagina. When a prior hysterectomy has led to a fistula, the vaginal fistula opening is typically located in the upper third of the vagina or at the vaginal cuff. If cuff sutures are still intact, this may also make localization of the fistula more difficult.

Leakage in the vagina can sometimes be detected with a retrograde filling of the bladder; other times, it is possible to detect leakage without filling the bladder. In all cases, it’s important to remember that more than one fistula – and more than one fistula type – may be present. A VVF and ureterovaginal fistula will sometimes occur together, which means that abnormal cystoscopy findings in a patient who experiences leakage does not necessarily rule out the presence of a concurrent ureterovaginal fistula.

Phenazopyridine (Pyridium) administered orally will turn the urine orange and can help visualize the leakage of urine into the vagina. When used in combination with the use of blue dye (methylene blue) infused into the bladder, a VVF may be distinguished from a ureterovaginal fistula. To completely evaluate the number and location of fistulas, however, imaging studies are necessary. In my experience, a CT urogram with IV contrast can also help localize ureteral injuries.

Surgical treatment

VVFs can almost always be repaired vaginally. If the fistula is too high in location or too complex, then an abdominal approach, either robotic, laparoscopic, or open, may be necessary. I prefer a vaginal approach to VVF repair whenever feasible because of its straightforward nature, lower morbidity, and high rate of success on the first attempt. Failure rates are between 5% and 20% for each attempt, so more than one surgery may be required. It is not unreasonable to attempt two or three vaginal approach repairs if each successive attempt results in a smaller fistula. A decision to go abdominal must be made based on the chances of a successful vaginal approach and on the patient’s wishes.

Successful fistula repair requires tension-free suture lines, no overlapping suture lines, and good vascular supply to the tissue. The timing of repair has long been controversial, but barring the presence of active pelvic infection, which may require an immediate surgical approach, the timing of fistula repair depends almost solely on the quality of the surrounding tissue. This relates to the need for a good vascular supply.

Early repair can be done if the tissue is pliable and healthy. But in general, if surgery is performed too close to the time of injury, the surrounding tissue will be erythematous and likely to break down with closure. The goal is to wait until the granulation tissue has dissipated and the area is no longer inflamed; after gynecologic surgery, this generally occurs within 6-12 weeks.

Regular vaginal exams about every 2 weeks can be used to monitor progress. During the waiting period, catheterization of the bladder can improve comfort for the patient and may even allow for spontaneous closure of the fistula. In fact, I usually tell patients who are diagnosed with a VVF within the first few weeks after surgery that spontaneous closure is a possible outcome given continuous urinary drainage for up to 30 days, provided that the VVF is small enough. This may be optimistic thinking on the part of the surgeon and the patient, but there is little downside to this approach.

The Latzko technique described in 1992 is still widely used for vaginal repair of VVFs. With this approach, the vaginal epithelium is incised around the fistula, and vaginal epithelial flaps are raised and removed around the fistula tract (in a circle of about 2-3 cm in diameter) for a multilayer approximation of healthy tissues. Several layers are sometimes needed, but in most cases, two layers are sufficient.

In my experience, a modified approach to the traditional Latzko procedure is more successful. Prior to closure, either anterior or posterior to the VVF, a small rim of vaginal epithelium is removed and, on the other side, the epithelium is mobilized at least 1 cm lateral to the fistula on both sides, and about 2 cm distal. This allows for the creation of a small, modified, thumbnail flap that completely patches the fistula closure without tension and without the need for any overlapping suture lines. The key is to secure flap tissue from the side where there appears to be more vaginal tissue. The tissue should be loose; if there appears to be any strain, the repair is likely to fail.

There are not enough data from the United States or other developed countries to demonstrate the superiority of this modified approach, but data from the obstetric population in Africa – and my own experience – suggest that it yields better outcomes.

A VVF that is larger may require the use of additional sources of tissue. A graft called the Martius graft, or labial fibrofatty tissue graft, is sometimes used to reinforce repairs of larger fistulas, even those that are high in the vaginal vault. The procedure involves a vertical incision on the inner side of the labium majus and detachment of fibroadipose tissue from its underlying bulbocavernosus muscle. This fat-pad flap is vascularized and thus serves as a pedicled graft. It can be tunneled under the vaginal epithelium to reach the site of closure. The procedure has limited use with the vaginal approach to VVF, but is important to be aware of.

Other sources of grafts or flaps that can sometimes be used with the vaginal approach include the gracilis muscle, the gluteal muscle and peritoneum, and fasciocutaneous tissue from the inner thigh.

The avoidance of overlapping suture lines and multiple layers of closure will help ensure a water-tight closure. If there is any leakage upon testing the integrity of the repair, particularly one that is vaginally approached, such leakage will continue and the repair will have been unsuccessful. In an abdominal surgery for VVF, a small amount of remaining leakage will probably resolve on its own after 10-14 days of catheter placement.

Placement of a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is controversial. It has been suggested that a JP drain placed on continuous suction will pull urine out of the bladder and increase the risk of a fistula. I don’t place a JP drain in my repairs as I find them to not be helpful. A cystogram can be done 1 week after repair to confirm healing, but there is some debate about whether or not the procedure is useful at that point. In my experience, if the patient does not have a cystogram and gets postrepair leakage, I have the same information as I would have obtained through a positive finding on a cystogram.

Dr. Garely is chair of obstetrics and gynecology and director of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at the South Nassau Communities Hospital, Oceanside, N.Y., and a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He has no disclosures related to this column.

Vesicovaginal fistulas (VVFs) are the most common type of urogenital fistulas – approximately three times more common than ureterovaginal fistulas – and can be a debilitating problem for women.

Most of the research published in recent years on VVFs and other urogenital fistulas comes from developing countries where these abnormal communications are a common complication of obstructed labor. In the United States, despite a relative paucity of data, VVFs are known to occur most often as a sequelae of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. Estimates of the incidence of VVF and other urogenital fistula formation are debated but have ranged from 0.5% or less after simple hysterectomy to as high as 2% after radical hysterectomy. Most VVFs are believed to occur after hysterectomy performed for benign disease, and many – but not all – are caused by inadvertent bladder injury that was not recognized intraoperatively.

Women who have had one or more cesarean deliveries and those who have had prior pelvic or vaginal surgery are at increased risk. In addition, both radiation therapy and inflammation that occur with diseases such as pelvic inflammatory disease or inflammatory bowel disease can negatively affect tissue quality and healing from surgical procedures – and can lead ultimately to the development of urogenital fistulas – although even less is known about incidence in these cases.

Prevention

Intraoperatively, VVFs may best be prevented through careful mobilization of the bladder off the vaginal wall, the use of delayed absorbable sutures (preferably Vicryl sutures), and the use of cystoscopy to assess the bladder for injury. If cystoscopy is not available, retrograde filling with a Foley catheter will still be helpful.

An overly aggressive approach to creating the bladder flap during hysterectomy and other surgeries can increase the risk of devascularization and the subsequent formation of fistulas. When the blood supply is found to have been compromised, affected tissue can be strengthened by oversewing with imbrication. When an inadvertent cystotomy is identified, repair is often best achieved with omental tissue interposed between the bladder and vagina. If there is any doubt about bladder integrity, an interposition graft between the bladder flap and the vaginal cuff will help reduce the incidence of fistula formation. Whenever overlapping suture lines occur (the vaginal cuff and the cystotomy repair), the risk of VVF formation will increase. Other than that using omentum, peritoneal grafts will also work well.

VVF formation may still occur, however, despite recognition and repair of an injury – and despite normal findings on cystoscopy. In patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other prior pelvic surgery, for example, tissue devascularization may cause a delayed injury, with the process of tissue necrosis and VVF formation occurring up to a month after surgery. It is important to appreciate the factors that predispose patients to VVF and to anticipate an increased risk, but in many cases of delayed VVF, it’s quite possible that nothing could have been done to prevent the problem.

Work-up

Vesicovaginal fistulas typically present as painless, continuous urine leakage from the vagina. The medical history should include standard questions about pelvic health history and symptom characteristics (in order to exclude hematuria or leakage of fluid other than urine), as well as questions aimed at differentiating symptoms of VVF from other causes of urinary incontinence, such as stress incontinence. In my experience, urine leakage is often incorrectly dismissed as stress incontinence when it is actually VVF. A high index of suspicion will help make an earlier diagnosis. This does not usually change the management, but helps manage the anxiety, expectations, and needs of the patient.

I recommend beginning the work-up for a suspected VVF with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder for injury. An irregular appearance of the bladder, signs of inflammation, and poor or absent ureteral efflux are often indicative of VVF in the presence of vaginal leakage. Following cystoscopy, I perform a split speculum examination of the vagina. Most injuries will be on the anterior wall or the apex (cuff). A recently formed fistula may appear as a hole or as a small, red area of granulation tissue with no visible opening.

It can be difficult to visualize the vaginal fistula opening of more mature fistulas; similarly, very small fistulas may be difficult to find because of their size and the anatomy of the vagina. When a prior hysterectomy has led to a fistula, the vaginal fistula opening is typically located in the upper third of the vagina or at the vaginal cuff. If cuff sutures are still intact, this may also make localization of the fistula more difficult.

Leakage in the vagina can sometimes be detected with a retrograde filling of the bladder; other times, it is possible to detect leakage without filling the bladder. In all cases, it’s important to remember that more than one fistula – and more than one fistula type – may be present. A VVF and ureterovaginal fistula will sometimes occur together, which means that abnormal cystoscopy findings in a patient who experiences leakage does not necessarily rule out the presence of a concurrent ureterovaginal fistula.

Phenazopyridine (Pyridium) administered orally will turn the urine orange and can help visualize the leakage of urine into the vagina. When used in combination with the use of blue dye (methylene blue) infused into the bladder, a VVF may be distinguished from a ureterovaginal fistula. To completely evaluate the number and location of fistulas, however, imaging studies are necessary. In my experience, a CT urogram with IV contrast can also help localize ureteral injuries.

Surgical treatment

VVFs can almost always be repaired vaginally. If the fistula is too high in location or too complex, then an abdominal approach, either robotic, laparoscopic, or open, may be necessary. I prefer a vaginal approach to VVF repair whenever feasible because of its straightforward nature, lower morbidity, and high rate of success on the first attempt. Failure rates are between 5% and 20% for each attempt, so more than one surgery may be required. It is not unreasonable to attempt two or three vaginal approach repairs if each successive attempt results in a smaller fistula. A decision to go abdominal must be made based on the chances of a successful vaginal approach and on the patient’s wishes.

Successful fistula repair requires tension-free suture lines, no overlapping suture lines, and good vascular supply to the tissue. The timing of repair has long been controversial, but barring the presence of active pelvic infection, which may require an immediate surgical approach, the timing of fistula repair depends almost solely on the quality of the surrounding tissue. This relates to the need for a good vascular supply.

Early repair can be done if the tissue is pliable and healthy. But in general, if surgery is performed too close to the time of injury, the surrounding tissue will be erythematous and likely to break down with closure. The goal is to wait until the granulation tissue has dissipated and the area is no longer inflamed; after gynecologic surgery, this generally occurs within 6-12 weeks.

Regular vaginal exams about every 2 weeks can be used to monitor progress. During the waiting period, catheterization of the bladder can improve comfort for the patient and may even allow for spontaneous closure of the fistula. In fact, I usually tell patients who are diagnosed with a VVF within the first few weeks after surgery that spontaneous closure is a possible outcome given continuous urinary drainage for up to 30 days, provided that the VVF is small enough. This may be optimistic thinking on the part of the surgeon and the patient, but there is little downside to this approach.

The Latzko technique described in 1992 is still widely used for vaginal repair of VVFs. With this approach, the vaginal epithelium is incised around the fistula, and vaginal epithelial flaps are raised and removed around the fistula tract (in a circle of about 2-3 cm in diameter) for a multilayer approximation of healthy tissues. Several layers are sometimes needed, but in most cases, two layers are sufficient.

In my experience, a modified approach to the traditional Latzko procedure is more successful. Prior to closure, either anterior or posterior to the VVF, a small rim of vaginal epithelium is removed and, on the other side, the epithelium is mobilized at least 1 cm lateral to the fistula on both sides, and about 2 cm distal. This allows for the creation of a small, modified, thumbnail flap that completely patches the fistula closure without tension and without the need for any overlapping suture lines. The key is to secure flap tissue from the side where there appears to be more vaginal tissue. The tissue should be loose; if there appears to be any strain, the repair is likely to fail.

There are not enough data from the United States or other developed countries to demonstrate the superiority of this modified approach, but data from the obstetric population in Africa – and my own experience – suggest that it yields better outcomes.

A VVF that is larger may require the use of additional sources of tissue. A graft called the Martius graft, or labial fibrofatty tissue graft, is sometimes used to reinforce repairs of larger fistulas, even those that are high in the vaginal vault. The procedure involves a vertical incision on the inner side of the labium majus and detachment of fibroadipose tissue from its underlying bulbocavernosus muscle. This fat-pad flap is vascularized and thus serves as a pedicled graft. It can be tunneled under the vaginal epithelium to reach the site of closure. The procedure has limited use with the vaginal approach to VVF, but is important to be aware of.

Other sources of grafts or flaps that can sometimes be used with the vaginal approach include the gracilis muscle, the gluteal muscle and peritoneum, and fasciocutaneous tissue from the inner thigh.

The avoidance of overlapping suture lines and multiple layers of closure will help ensure a water-tight closure. If there is any leakage upon testing the integrity of the repair, particularly one that is vaginally approached, such leakage will continue and the repair will have been unsuccessful. In an abdominal surgery for VVF, a small amount of remaining leakage will probably resolve on its own after 10-14 days of catheter placement.

Placement of a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is controversial. It has been suggested that a JP drain placed on continuous suction will pull urine out of the bladder and increase the risk of a fistula. I don’t place a JP drain in my repairs as I find them to not be helpful. A cystogram can be done 1 week after repair to confirm healing, but there is some debate about whether or not the procedure is useful at that point. In my experience, if the patient does not have a cystogram and gets postrepair leakage, I have the same information as I would have obtained through a positive finding on a cystogram.

Dr. Garely is chair of obstetrics and gynecology and director of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at the South Nassau Communities Hospital, Oceanside, N.Y., and a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He has no disclosures related to this column.

Vesicovaginal fistulas (VVFs) are the most common type of urogenital fistulas – approximately three times more common than ureterovaginal fistulas – and can be a debilitating problem for women.

Most of the research published in recent years on VVFs and other urogenital fistulas comes from developing countries where these abnormal communications are a common complication of obstructed labor. In the United States, despite a relative paucity of data, VVFs are known to occur most often as a sequelae of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. Estimates of the incidence of VVF and other urogenital fistula formation are debated but have ranged from 0.5% or less after simple hysterectomy to as high as 2% after radical hysterectomy. Most VVFs are believed to occur after hysterectomy performed for benign disease, and many – but not all – are caused by inadvertent bladder injury that was not recognized intraoperatively.

Women who have had one or more cesarean deliveries and those who have had prior pelvic or vaginal surgery are at increased risk. In addition, both radiation therapy and inflammation that occur with diseases such as pelvic inflammatory disease or inflammatory bowel disease can negatively affect tissue quality and healing from surgical procedures – and can lead ultimately to the development of urogenital fistulas – although even less is known about incidence in these cases.

Prevention

Intraoperatively, VVFs may best be prevented through careful mobilization of the bladder off the vaginal wall, the use of delayed absorbable sutures (preferably Vicryl sutures), and the use of cystoscopy to assess the bladder for injury. If cystoscopy is not available, retrograde filling with a Foley catheter will still be helpful.

An overly aggressive approach to creating the bladder flap during hysterectomy and other surgeries can increase the risk of devascularization and the subsequent formation of fistulas. When the blood supply is found to have been compromised, affected tissue can be strengthened by oversewing with imbrication. When an inadvertent cystotomy is identified, repair is often best achieved with omental tissue interposed between the bladder and vagina. If there is any doubt about bladder integrity, an interposition graft between the bladder flap and the vaginal cuff will help reduce the incidence of fistula formation. Whenever overlapping suture lines occur (the vaginal cuff and the cystotomy repair), the risk of VVF formation will increase. Other than that using omentum, peritoneal grafts will also work well.

VVF formation may still occur, however, despite recognition and repair of an injury – and despite normal findings on cystoscopy. In patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other prior pelvic surgery, for example, tissue devascularization may cause a delayed injury, with the process of tissue necrosis and VVF formation occurring up to a month after surgery. It is important to appreciate the factors that predispose patients to VVF and to anticipate an increased risk, but in many cases of delayed VVF, it’s quite possible that nothing could have been done to prevent the problem.

Work-up

Vesicovaginal fistulas typically present as painless, continuous urine leakage from the vagina. The medical history should include standard questions about pelvic health history and symptom characteristics (in order to exclude hematuria or leakage of fluid other than urine), as well as questions aimed at differentiating symptoms of VVF from other causes of urinary incontinence, such as stress incontinence. In my experience, urine leakage is often incorrectly dismissed as stress incontinence when it is actually VVF. A high index of suspicion will help make an earlier diagnosis. This does not usually change the management, but helps manage the anxiety, expectations, and needs of the patient.

I recommend beginning the work-up for a suspected VVF with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder for injury. An irregular appearance of the bladder, signs of inflammation, and poor or absent ureteral efflux are often indicative of VVF in the presence of vaginal leakage. Following cystoscopy, I perform a split speculum examination of the vagina. Most injuries will be on the anterior wall or the apex (cuff). A recently formed fistula may appear as a hole or as a small, red area of granulation tissue with no visible opening.

It can be difficult to visualize the vaginal fistula opening of more mature fistulas; similarly, very small fistulas may be difficult to find because of their size and the anatomy of the vagina. When a prior hysterectomy has led to a fistula, the vaginal fistula opening is typically located in the upper third of the vagina or at the vaginal cuff. If cuff sutures are still intact, this may also make localization of the fistula more difficult.

Leakage in the vagina can sometimes be detected with a retrograde filling of the bladder; other times, it is possible to detect leakage without filling the bladder. In all cases, it’s important to remember that more than one fistula – and more than one fistula type – may be present. A VVF and ureterovaginal fistula will sometimes occur together, which means that abnormal cystoscopy findings in a patient who experiences leakage does not necessarily rule out the presence of a concurrent ureterovaginal fistula.

Phenazopyridine (Pyridium) administered orally will turn the urine orange and can help visualize the leakage of urine into the vagina. When used in combination with the use of blue dye (methylene blue) infused into the bladder, a VVF may be distinguished from a ureterovaginal fistula. To completely evaluate the number and location of fistulas, however, imaging studies are necessary. In my experience, a CT urogram with IV contrast can also help localize ureteral injuries.

Surgical treatment

VVFs can almost always be repaired vaginally. If the fistula is too high in location or too complex, then an abdominal approach, either robotic, laparoscopic, or open, may be necessary. I prefer a vaginal approach to VVF repair whenever feasible because of its straightforward nature, lower morbidity, and high rate of success on the first attempt. Failure rates are between 5% and 20% for each attempt, so more than one surgery may be required. It is not unreasonable to attempt two or three vaginal approach repairs if each successive attempt results in a smaller fistula. A decision to go abdominal must be made based on the chances of a successful vaginal approach and on the patient’s wishes.

Successful fistula repair requires tension-free suture lines, no overlapping suture lines, and good vascular supply to the tissue. The timing of repair has long been controversial, but barring the presence of active pelvic infection, which may require an immediate surgical approach, the timing of fistula repair depends almost solely on the quality of the surrounding tissue. This relates to the need for a good vascular supply.

Early repair can be done if the tissue is pliable and healthy. But in general, if surgery is performed too close to the time of injury, the surrounding tissue will be erythematous and likely to break down with closure. The goal is to wait until the granulation tissue has dissipated and the area is no longer inflamed; after gynecologic surgery, this generally occurs within 6-12 weeks.

Regular vaginal exams about every 2 weeks can be used to monitor progress. During the waiting period, catheterization of the bladder can improve comfort for the patient and may even allow for spontaneous closure of the fistula. In fact, I usually tell patients who are diagnosed with a VVF within the first few weeks after surgery that spontaneous closure is a possible outcome given continuous urinary drainage for up to 30 days, provided that the VVF is small enough. This may be optimistic thinking on the part of the surgeon and the patient, but there is little downside to this approach.

The Latzko technique described in 1992 is still widely used for vaginal repair of VVFs. With this approach, the vaginal epithelium is incised around the fistula, and vaginal epithelial flaps are raised and removed around the fistula tract (in a circle of about 2-3 cm in diameter) for a multilayer approximation of healthy tissues. Several layers are sometimes needed, but in most cases, two layers are sufficient.

In my experience, a modified approach to the traditional Latzko procedure is more successful. Prior to closure, either anterior or posterior to the VVF, a small rim of vaginal epithelium is removed and, on the other side, the epithelium is mobilized at least 1 cm lateral to the fistula on both sides, and about 2 cm distal. This allows for the creation of a small, modified, thumbnail flap that completely patches the fistula closure without tension and without the need for any overlapping suture lines. The key is to secure flap tissue from the side where there appears to be more vaginal tissue. The tissue should be loose; if there appears to be any strain, the repair is likely to fail.

There are not enough data from the United States or other developed countries to demonstrate the superiority of this modified approach, but data from the obstetric population in Africa – and my own experience – suggest that it yields better outcomes.

A VVF that is larger may require the use of additional sources of tissue. A graft called the Martius graft, or labial fibrofatty tissue graft, is sometimes used to reinforce repairs of larger fistulas, even those that are high in the vaginal vault. The procedure involves a vertical incision on the inner side of the labium majus and detachment of fibroadipose tissue from its underlying bulbocavernosus muscle. This fat-pad flap is vascularized and thus serves as a pedicled graft. It can be tunneled under the vaginal epithelium to reach the site of closure. The procedure has limited use with the vaginal approach to VVF, but is important to be aware of.

Other sources of grafts or flaps that can sometimes be used with the vaginal approach include the gracilis muscle, the gluteal muscle and peritoneum, and fasciocutaneous tissue from the inner thigh.

The avoidance of overlapping suture lines and multiple layers of closure will help ensure a water-tight closure. If there is any leakage upon testing the integrity of the repair, particularly one that is vaginally approached, such leakage will continue and the repair will have been unsuccessful. In an abdominal surgery for VVF, a small amount of remaining leakage will probably resolve on its own after 10-14 days of catheter placement.

Placement of a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is controversial. It has been suggested that a JP drain placed on continuous suction will pull urine out of the bladder and increase the risk of a fistula. I don’t place a JP drain in my repairs as I find them to not be helpful. A cystogram can be done 1 week after repair to confirm healing, but there is some debate about whether or not the procedure is useful at that point. In my experience, if the patient does not have a cystogram and gets postrepair leakage, I have the same information as I would have obtained through a positive finding on a cystogram.

Dr. Garely is chair of obstetrics and gynecology and director of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at the South Nassau Communities Hospital, Oceanside, N.Y., and a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He has no disclosures related to this column.

Another study links genital prolapse to incontinence

Objective

Researchers investigated the rate of anal incontinence in women who present with urinary incontinence and genital prolapse.

Method and results

In this study of almost 900 women, 20% of those with urinary incontinence and pelvic-organ prolapse also had anal incontinence. Subjects completed a bowel questionnaire and underwent a detailed exam. Researchers noted associations between anal incontinence and infant birth weights of 3,800 g or greater, rectocele greater than grade 2, urinary incontinence, hemorrhoidectomy, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Numerous studies report similar rates of anal incontinence associated with genital prolapse.1,2

Expert commentary

The social stigma of anal incontinence is not to be underestimated. Given the risk for anal incontinence from vaginal delivery and the inherent risks of elective cesarean section, which should we recommend for our patients? With the evidence before us, now is the time for a paradigm shift. While some academics and women’s rights groups dispute the utility and safety of elective cesarean delivery, investigations such as this one indicate that, in selected patients, it may be better.

Meschia and colleagues found a strong association between anal incontinence and urinary incontinence and genital prolapse, noting that this evidence is “consistent with the theory of a common pathogen mechanism for anal and genuine stress incontinence.” But do we really need more studies telling us that women who deliver large babies have more pelvic-floor dysfunction? As any pelvic reconstructive surgeon can attest, pelvic prolapse, urinary and fecal incontinence, and pelvic-floor dysfunction are epidemic. In a recent survey of obstetricians, many indicated that, given the choice, they would opt for elective cesarean section for themselves or family members.3

Many doctors resist when a patient asks for a specific mode of delivery. These physicians may feel such a request undermines their authority and somehow implies that a layperson knows best. When the evidence yields a clear message, however, it should be heeded: Cesarean delivery has a protective effect on the pelvis.

As O’Boyle outlines in an excellent opinion paper,4 we can set policy based on antiquated concepts, or we can conduct open, informed discussions with patients in the spirit of a true partnership and mutual decision-making.

Bottom line

Doctors don’t cause pelvic dysfunction during delivery, nature does. By communicating this concept we can help our patients make choices—and limit our already-catastrophic exposure to litigation.

1. McArthur C, Bick D, Keighley M. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:46-50.

2. Sultan AH, Kamn MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Land R, Parry A, Rane A, Wilson D. Personal p of obstetricians towards childbirth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:249-252.

4. O’Boyle AL, Davis GD, Calhoun BC. Informed consent and birth: Protecting the pelvic floor and ourselves. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:981-983.

Objective

Researchers investigated the rate of anal incontinence in women who present with urinary incontinence and genital prolapse.

Method and results

In this study of almost 900 women, 20% of those with urinary incontinence and pelvic-organ prolapse also had anal incontinence. Subjects completed a bowel questionnaire and underwent a detailed exam. Researchers noted associations between anal incontinence and infant birth weights of 3,800 g or greater, rectocele greater than grade 2, urinary incontinence, hemorrhoidectomy, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Numerous studies report similar rates of anal incontinence associated with genital prolapse.1,2

Expert commentary

The social stigma of anal incontinence is not to be underestimated. Given the risk for anal incontinence from vaginal delivery and the inherent risks of elective cesarean section, which should we recommend for our patients? With the evidence before us, now is the time for a paradigm shift. While some academics and women’s rights groups dispute the utility and safety of elective cesarean delivery, investigations such as this one indicate that, in selected patients, it may be better.

Meschia and colleagues found a strong association between anal incontinence and urinary incontinence and genital prolapse, noting that this evidence is “consistent with the theory of a common pathogen mechanism for anal and genuine stress incontinence.” But do we really need more studies telling us that women who deliver large babies have more pelvic-floor dysfunction? As any pelvic reconstructive surgeon can attest, pelvic prolapse, urinary and fecal incontinence, and pelvic-floor dysfunction are epidemic. In a recent survey of obstetricians, many indicated that, given the choice, they would opt for elective cesarean section for themselves or family members.3

Many doctors resist when a patient asks for a specific mode of delivery. These physicians may feel such a request undermines their authority and somehow implies that a layperson knows best. When the evidence yields a clear message, however, it should be heeded: Cesarean delivery has a protective effect on the pelvis.

As O’Boyle outlines in an excellent opinion paper,4 we can set policy based on antiquated concepts, or we can conduct open, informed discussions with patients in the spirit of a true partnership and mutual decision-making.

Bottom line

Doctors don’t cause pelvic dysfunction during delivery, nature does. By communicating this concept we can help our patients make choices—and limit our already-catastrophic exposure to litigation.

Objective

Researchers investigated the rate of anal incontinence in women who present with urinary incontinence and genital prolapse.

Method and results

In this study of almost 900 women, 20% of those with urinary incontinence and pelvic-organ prolapse also had anal incontinence. Subjects completed a bowel questionnaire and underwent a detailed exam. Researchers noted associations between anal incontinence and infant birth weights of 3,800 g or greater, rectocele greater than grade 2, urinary incontinence, hemorrhoidectomy, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Numerous studies report similar rates of anal incontinence associated with genital prolapse.1,2

Expert commentary

The social stigma of anal incontinence is not to be underestimated. Given the risk for anal incontinence from vaginal delivery and the inherent risks of elective cesarean section, which should we recommend for our patients? With the evidence before us, now is the time for a paradigm shift. While some academics and women’s rights groups dispute the utility and safety of elective cesarean delivery, investigations such as this one indicate that, in selected patients, it may be better.

Meschia and colleagues found a strong association between anal incontinence and urinary incontinence and genital prolapse, noting that this evidence is “consistent with the theory of a common pathogen mechanism for anal and genuine stress incontinence.” But do we really need more studies telling us that women who deliver large babies have more pelvic-floor dysfunction? As any pelvic reconstructive surgeon can attest, pelvic prolapse, urinary and fecal incontinence, and pelvic-floor dysfunction are epidemic. In a recent survey of obstetricians, many indicated that, given the choice, they would opt for elective cesarean section for themselves or family members.3

Many doctors resist when a patient asks for a specific mode of delivery. These physicians may feel such a request undermines their authority and somehow implies that a layperson knows best. When the evidence yields a clear message, however, it should be heeded: Cesarean delivery has a protective effect on the pelvis.

As O’Boyle outlines in an excellent opinion paper,4 we can set policy based on antiquated concepts, or we can conduct open, informed discussions with patients in the spirit of a true partnership and mutual decision-making.

Bottom line

Doctors don’t cause pelvic dysfunction during delivery, nature does. By communicating this concept we can help our patients make choices—and limit our already-catastrophic exposure to litigation.

1. McArthur C, Bick D, Keighley M. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:46-50.

2. Sultan AH, Kamn MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Land R, Parry A, Rane A, Wilson D. Personal p of obstetricians towards childbirth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:249-252.

4. O’Boyle AL, Davis GD, Calhoun BC. Informed consent and birth: Protecting the pelvic floor and ourselves. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:981-983.

1. McArthur C, Bick D, Keighley M. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:46-50.

2. Sultan AH, Kamn MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Land R, Parry A, Rane A, Wilson D. Personal p of obstetricians towards childbirth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:249-252.

4. O’Boyle AL, Davis GD, Calhoun BC. Informed consent and birth: Protecting the pelvic floor and ourselves. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:981-983.