User login

Adult ADHD: Tips for an accurate diagnosis

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

With the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the rise1 and a surge in prescriptions to treat the disorder leading to stimulant shortages,2 ensuring that patients are appropriately evaluated for ADHD is more critical than ever. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis that can be established by clinical interview, although the results of neuropsychological testing and collateral information from family members are helpful. Assessing adults for ADHD can be challenging when they appear to want to convince the clinician that they have the disorder. In this article, I provide tips to help you accurately diagnose ADHD in adult patients.

Use an ADHD symptom scale

An ADHD symptom checklist, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, is an effective tool to establish the presence of ADHD symptoms. A patient can complete this self-assessment tool before their visit, and you can use the results as a springboard to ask them about ADHD symptoms. It is important to elicit specific examples of the ADHD symptoms the patient reports, and to understand how these symptoms affect their functioning and quality of life.

Review the prescription drug monitoring program

Review your state’s prescription drug monitoring program to explore the patient’s prior and current prescriptions of stimulants and other controlled substances. Discern if, when, and by whom a patient was previously treated for ADHD, and rule out the rare possibility that the patient has obtained multiple prescriptions for controlled substances from multiple clinicians, which suggests the patient may have a substance use disorder.

Begin the assessment at your initial contact with the patient

How patients present on an initial screening call or how they compose emails can reveal clues about their level of organization and overall executive functioning. The way patients complete intake forms (eg, using a concise vs a meandering writing style) as well as their punctuality when presenting to appointments can also be telling.

Conduct a mental status examination

Patients can have difficulty focusing and completing tasks for reasons other than having ADHD. A mental status examination can sometimes provide objective clues that an individual has ADHD. A digressive thought process, visible physical restlessness, and instances of a patient interrupting the evaluator are suggestive of ADHD, although all these symptoms can be present in other conditions (eg, mania). However, signs of ADHD in the mental status examination do not confirm an ADHD diagnosis, nor does their absence rule it out.

Maintain an appropriate diagnostic threshold

Per DSM-5, an ADHD diagnosis requires that the symptoms cause a significant impairment in functioning.3 It is up to the clinician to determine if this threshold is met. It is imperative to thoughtfully consider this because stimulants are first-line treatment for ADHD and are commonly misused. Psychiatrists are usually motivated to please their patients in order to maintain them as patients and develop a positive therapeutic relationship, which improves outcomes.4 However, it is important to demonstrate integrity, provide an accurate diagnosis, and not be unduly swayed by a patient’s wish to receive an ADHD diagnosis. If you sense that a prospective patient is hoping they will receive an ADHD diagnosis and be prescribed a stimulant, it may be prudent to emphasize that the patient will be assessed for multiple mental health conditions, including ADHD, and that treatment will depend on the outcome of the evaluation.

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

1. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

2. Danielson ML, Bohm MK, Newsome K, et al. Trends in stimulant prescription fills among commercially insured children and adults - United States, 2016-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(13):327-332. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7213a1

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59-63.

4. Totura CMW, Fields SA, Karver MS. The role of the therapeutic relationship in psychopharmacological treatment outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Pyschiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):41-47. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700114

Increased anxiety and depression after menstruation

CASE Increased anxiety and depression

Ms. C, age 29, has bipolar II disorder (BD II) and generalized anxiety disorder. She presents to her outpatient psychiatrist seeking relief from chronic and significant dips in her mood from Day 5 to Day 15 of her menstrual cycle. During this time, she says she experiences increased anxiety, insomnia, frequent tearfulness, and intermittent suicidal ideation.

Ms. C meticulously charts her menstrual cycle using a smartphone app and reports having a regular 28-day cycle. She says she has experienced this worsening of symptoms since the onset of menarche, but her mood generally stabilizes after Day 14 of her cycle–around the time of ovulation–and remains euthymic throughout the premenstrual period.

HISTORY Depression and a change in medication

Ms. C has a history of major depressive episodes and has experienced hypomanic episodes that lasted 1 to 2 weeks and were associated with an elevated mood, high energy, rapid speech, and increased self-confidence. Ms. C says she has chronically high anxiety associated with trouble sleeping, difficulty focusing, restlessness, and muscle tension. When she was receiving care from previous psychiatrists, treatment with lithium, quetiapine, lamotrigine, sertraline, and fluoxetine was not successful, and Ms. C said she had severe anxiety when she tried sertraline and fluoxetine. After several months of substantial mood instability and high anxiety, Ms. C responded well to pregabalin 100 mg 3 times a day, lurasidone 60 mg/d at bedtime, and gabapentin 500 mg/d at bedtime. Over the last 4 months, she reports that her overall mood has been even, and she has been coping well with her anxiety.

Ms. C is married with no children. She uses condoms for birth control. She previously tried taking a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive, but stopped because she said it made her feel very depressed. Ms. C reports no history of substance use. She is employed, says she has many positive relationships, and does not have a social history suggestive of a personality disorder.

[polldaddy:11818926]

The author’s observations

Many women report worsening of mood during the premenstrual period (luteal phase). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) involves symptoms that develop during the luteal phase and end shortly after menstruation; this condition impacts ≤5% of women.1 The etiology of PMDD appears to involve contributions from genetics, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite), brain-derived neurotrophic factor, brain structural and functional differences, and hypothalamic pathways.2

Researchers have postulated that the precipitous decline in the levels of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the luteal phase may contribute to the mood symptoms of PMDD.2 Allopregnanolone is a modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors and may exert anxiolytic and sedative effects. Women who experience PMDD may be less sensitive to the effects of allopregnanolone.3 Additionally, early luteal phase levels of estrogen may predict late luteal phase symptoms of PMDD.4 The mechanism involved may be estrogen’s effect on the serotonin system. The HPA axis may also be involved in the etiology of PMDD because patients with this condition appear to have a blunted cortisol response in reaction to stress.5 Research also has implicated immune activation and inflammation in the etiology of PMDD.6

A PMDD diagnosis should be distinguished from a premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric condition, which occurs when a patient has an untreated primary mood or anxiety disorder that worsens during the premenstrual period. PMDD is differentiated from premenstrual syndrome by the severity of symptoms.2 The recommended first-line treatment of PMDD is an SSRI, but if an SSRI does not work, is not tolerated, or is not preferred for any other reason, recommended alternatives include combined hormone oral contraceptive pills, dutasteride, gabapentin, or various supplements.7,8 PMDD has been widely studied and is treated by both psychiatrists and gynecologists. In addition, some women report experiencing mood instability around ovulation. Kiesner9 found that 13% of women studied showed an increased negative mood state midcycle, rather than during the premenstrual period.

Continue to: Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual mood symptoms are atypical. Postmenstrual syndrome is not listed in DSM-5 or formally recognized as a medical diagnosis. Peer-reviewed research or literature on the condition is scarce to nonexistent. However, it has been discussed by physicians in articles in the lay press. One gynecologist and reproductive endocrinologist estimated that approximately 10% of women experience significant physical and emotional symptoms postmenstruation.10 An internist and women’s health specialist suggested that the cause of postmenstrual syndrome might be a surge in levels of estrogen and testosterone and may be associated with insulin resistance and polycystic ovarian syndrome, while another possible contribution could be iron deficiency caused by loss of blood from menstruation.11

TREATMENT Recommending an oral contraceptive

Ms. C’s psychiatrist does not prescribe an SSRI because he is concerned it would destabilize her BD II. The patient also had negative experiences in her past 2 trials of SSRIs.

Because the psychiatrist believes it is prudent to optimize the dosages of a patient’s current medication before starting a new medication or intervention, he considers increasing Ms. C’s dosage of lurasidone or pregabalin. The rationale for optimizing Ms. C’s current medication regimen is that greater overall mood stability would likely result in less severe postmenstrual mood symptoms. However, Ms. C does not want to increase her dosage of either medication because she is concerned about adverse effects.

Ms. C’s psychiatrist discusses the case with 2 gynecologist/obstetrician colleagues. One suggests the patient try a progesterone-only oral contraceptive and the other suggests a trial of Prometrium (a progesterone capsule used to treat endometrial hyperplasia and secondary amenorrhea). Both suggestions are based on the theory that Ms. C may be sensitive to levels of progesterone, which are low during the follicular phase and rise after ovulation; neither recommendation is evidence-based. A low level of allopregnanolone may lead to less GABAergic activity and consequently greater mood dysregulation. Some women are particularly sensitive to low levels of allopregnanolone in the follicular phase, which might lead to postmenstrual mood symptoms. Additionally, Ms. C’s previous treatment with a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive may have decreased her level of allopregnanolone.12 Ultimately, Ms. C’s psychiatrist suggests that she take a progesterone-only oral contraceptive.

The author’s observations

Guidance on how to treat Ms. C’s postmenstrual symptoms came from research on how to treat PMDD in patients who have BD. In a review of managing PMDD in women with BD, Sepede et al13 presented a treatment algorithm that recommends a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive as first-line treatment in euthymic patients who are already receiving an optimal dose of mood stabilizers. Sepede et al13 expressed caution about using SSRIs due to the risk of inducing mood changes, but recommended SSRIs for patients with comorbid PMDD and BD who experience a depressive episode.

Another question is which type of oral contraceptive is most effective for treating PMDD. The combined oral contraceptive drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol has the most evidence for efficacy.14 Combined oral contraceptives carry risks of venous thromboembolism, hypertension, stroke, migraines, and liver complications, and are possibly associated with certain types of cancer, such as breast and cervical cancer.15 Their use is contraindicated in patients with a history of these conditions and for women age >35 who smoke ≥15 cigarettes/d.

The limited research that has examined the efficacy of progestin-only oral contraceptives for treating PMDD has been inconclusive.16 However, progesterone-only oral contraceptives are associated with less overall risk than combined oral contraceptives, and many women opt to use progesterone-only oral contraceptives due to concerns about possible adverse effects of the combined formulations. A substantial drawback of progesterone-only oral contraceptives is they must be taken at the same time every day, and if a dose is taken late, these agents may lose their efficacy in preventing pregnancy (and a backup birth control method must be used17). Additionally, drospirenone, a progestin that is a component of many oral contraceptives, has antimineralocorticoid properties and is contraindicated in patients with kidney or adrenal gland insufficiency or liver disease. As was the case when Ms. C initially took a combined contraceptive, hormonal contraceptives can sometimes cause mood dysregulation.

Continue to: OUTCOME Improved symptoms

OUTCOME Improved symptoms

Ms. C meets with her gynecologist, who prescribes norethindrone, a progestin-only oral contraceptive. Since taking norethindrone, Ms. C reports a dramatic improvement in the mood symptoms she experiences during the postmenstrual period.

Bottom Line

Some women may experience mood symptoms during the postmenstrual period that are similar to the symptoms experienced by patients who have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). This phenomenon has been described as postmenstrual syndrome, and though evidence is lacking, treating it similarly to PMDD may be effective.

Related Resources

- Ray P, Mandal N, Sinha VK. Change of symptoms of schizophrenia across phases of menstrual cycle. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s00737-019-0952-4

- Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

Drug Brand Names

Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol • Yasmin

Dutasteride • Avodart

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Progesterone • Prometrium

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

2. Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

3. Timby E, Bäckström T, Nyberg S, et al. Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have altered sensitivity to allopregnanolone over the menstrual cycle compared to controls--a pilot study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(11):2109-2117.

4. Yen JY, Lin HC, Lin PC, et al. Early- and late-luteal-phase estrogen and progesterone levels of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4352.

5. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

6. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

7. Tiranini L, Nappi RE. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Rev. 2022:11:(11). doi:10.12703/r/11-11

8. Raffi ER. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/145089/somatic-disorders/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder

9. Kiesner J. One woman’s low is another woman’s high: paradoxical effects of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(1):68-76.

10. Alnuweiri T. Feel low after your period? Postmenstrual syndrome could be the reason. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.wellandgood.com/pms-after-period/

11. Sharkey L. Everything you need to know about post-menstrual syndrome. Healthline. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.healthline.com/health/post-menstrual-syndrome

12. Santoru F, Berretti R, Locci A, et al. Decreased allopregnanolone induced by hormonal contraceptives is associated with a reduction in social behavior and sexual motivation in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3351-3364.

13. Sepede G, Brunetti M, Di Giannantonio M. Comorbid premenstrual dysphoric disorder in women with bipolar disorder: management challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2020;16:415-426.

14. Rapkin AJ, Korotkaya Y, Taylor KC. Contraception counseling for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): current perspectives. Open Access J Contraception. 2019;10:27-39. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S183193

15. Roe AH, Bartz DA, Douglas PS. Combined estrogen-progestin contraception: side effects and health concerns. UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/combined-estrogen-progestin-contraception-side-effects-and-health-concerns

16. Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, et al. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2012;3:CD003415. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4

17. Kaunitz AM. Contraception: progestin-only pills (POPs). UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/contraception-progestin-only-pills-pops

CASE Increased anxiety and depression

Ms. C, age 29, has bipolar II disorder (BD II) and generalized anxiety disorder. She presents to her outpatient psychiatrist seeking relief from chronic and significant dips in her mood from Day 5 to Day 15 of her menstrual cycle. During this time, she says she experiences increased anxiety, insomnia, frequent tearfulness, and intermittent suicidal ideation.

Ms. C meticulously charts her menstrual cycle using a smartphone app and reports having a regular 28-day cycle. She says she has experienced this worsening of symptoms since the onset of menarche, but her mood generally stabilizes after Day 14 of her cycle–around the time of ovulation–and remains euthymic throughout the premenstrual period.

HISTORY Depression and a change in medication

Ms. C has a history of major depressive episodes and has experienced hypomanic episodes that lasted 1 to 2 weeks and were associated with an elevated mood, high energy, rapid speech, and increased self-confidence. Ms. C says she has chronically high anxiety associated with trouble sleeping, difficulty focusing, restlessness, and muscle tension. When she was receiving care from previous psychiatrists, treatment with lithium, quetiapine, lamotrigine, sertraline, and fluoxetine was not successful, and Ms. C said she had severe anxiety when she tried sertraline and fluoxetine. After several months of substantial mood instability and high anxiety, Ms. C responded well to pregabalin 100 mg 3 times a day, lurasidone 60 mg/d at bedtime, and gabapentin 500 mg/d at bedtime. Over the last 4 months, she reports that her overall mood has been even, and she has been coping well with her anxiety.

Ms. C is married with no children. She uses condoms for birth control. She previously tried taking a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive, but stopped because she said it made her feel very depressed. Ms. C reports no history of substance use. She is employed, says she has many positive relationships, and does not have a social history suggestive of a personality disorder.

[polldaddy:11818926]

The author’s observations

Many women report worsening of mood during the premenstrual period (luteal phase). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) involves symptoms that develop during the luteal phase and end shortly after menstruation; this condition impacts ≤5% of women.1 The etiology of PMDD appears to involve contributions from genetics, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite), brain-derived neurotrophic factor, brain structural and functional differences, and hypothalamic pathways.2

Researchers have postulated that the precipitous decline in the levels of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the luteal phase may contribute to the mood symptoms of PMDD.2 Allopregnanolone is a modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors and may exert anxiolytic and sedative effects. Women who experience PMDD may be less sensitive to the effects of allopregnanolone.3 Additionally, early luteal phase levels of estrogen may predict late luteal phase symptoms of PMDD.4 The mechanism involved may be estrogen’s effect on the serotonin system. The HPA axis may also be involved in the etiology of PMDD because patients with this condition appear to have a blunted cortisol response in reaction to stress.5 Research also has implicated immune activation and inflammation in the etiology of PMDD.6

A PMDD diagnosis should be distinguished from a premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric condition, which occurs when a patient has an untreated primary mood or anxiety disorder that worsens during the premenstrual period. PMDD is differentiated from premenstrual syndrome by the severity of symptoms.2 The recommended first-line treatment of PMDD is an SSRI, but if an SSRI does not work, is not tolerated, or is not preferred for any other reason, recommended alternatives include combined hormone oral contraceptive pills, dutasteride, gabapentin, or various supplements.7,8 PMDD has been widely studied and is treated by both psychiatrists and gynecologists. In addition, some women report experiencing mood instability around ovulation. Kiesner9 found that 13% of women studied showed an increased negative mood state midcycle, rather than during the premenstrual period.

Continue to: Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual mood symptoms are atypical. Postmenstrual syndrome is not listed in DSM-5 or formally recognized as a medical diagnosis. Peer-reviewed research or literature on the condition is scarce to nonexistent. However, it has been discussed by physicians in articles in the lay press. One gynecologist and reproductive endocrinologist estimated that approximately 10% of women experience significant physical and emotional symptoms postmenstruation.10 An internist and women’s health specialist suggested that the cause of postmenstrual syndrome might be a surge in levels of estrogen and testosterone and may be associated with insulin resistance and polycystic ovarian syndrome, while another possible contribution could be iron deficiency caused by loss of blood from menstruation.11

TREATMENT Recommending an oral contraceptive

Ms. C’s psychiatrist does not prescribe an SSRI because he is concerned it would destabilize her BD II. The patient also had negative experiences in her past 2 trials of SSRIs.

Because the psychiatrist believes it is prudent to optimize the dosages of a patient’s current medication before starting a new medication or intervention, he considers increasing Ms. C’s dosage of lurasidone or pregabalin. The rationale for optimizing Ms. C’s current medication regimen is that greater overall mood stability would likely result in less severe postmenstrual mood symptoms. However, Ms. C does not want to increase her dosage of either medication because she is concerned about adverse effects.

Ms. C’s psychiatrist discusses the case with 2 gynecologist/obstetrician colleagues. One suggests the patient try a progesterone-only oral contraceptive and the other suggests a trial of Prometrium (a progesterone capsule used to treat endometrial hyperplasia and secondary amenorrhea). Both suggestions are based on the theory that Ms. C may be sensitive to levels of progesterone, which are low during the follicular phase and rise after ovulation; neither recommendation is evidence-based. A low level of allopregnanolone may lead to less GABAergic activity and consequently greater mood dysregulation. Some women are particularly sensitive to low levels of allopregnanolone in the follicular phase, which might lead to postmenstrual mood symptoms. Additionally, Ms. C’s previous treatment with a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive may have decreased her level of allopregnanolone.12 Ultimately, Ms. C’s psychiatrist suggests that she take a progesterone-only oral contraceptive.

The author’s observations

Guidance on how to treat Ms. C’s postmenstrual symptoms came from research on how to treat PMDD in patients who have BD. In a review of managing PMDD in women with BD, Sepede et al13 presented a treatment algorithm that recommends a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive as first-line treatment in euthymic patients who are already receiving an optimal dose of mood stabilizers. Sepede et al13 expressed caution about using SSRIs due to the risk of inducing mood changes, but recommended SSRIs for patients with comorbid PMDD and BD who experience a depressive episode.

Another question is which type of oral contraceptive is most effective for treating PMDD. The combined oral contraceptive drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol has the most evidence for efficacy.14 Combined oral contraceptives carry risks of venous thromboembolism, hypertension, stroke, migraines, and liver complications, and are possibly associated with certain types of cancer, such as breast and cervical cancer.15 Their use is contraindicated in patients with a history of these conditions and for women age >35 who smoke ≥15 cigarettes/d.

The limited research that has examined the efficacy of progestin-only oral contraceptives for treating PMDD has been inconclusive.16 However, progesterone-only oral contraceptives are associated with less overall risk than combined oral contraceptives, and many women opt to use progesterone-only oral contraceptives due to concerns about possible adverse effects of the combined formulations. A substantial drawback of progesterone-only oral contraceptives is they must be taken at the same time every day, and if a dose is taken late, these agents may lose their efficacy in preventing pregnancy (and a backup birth control method must be used17). Additionally, drospirenone, a progestin that is a component of many oral contraceptives, has antimineralocorticoid properties and is contraindicated in patients with kidney or adrenal gland insufficiency or liver disease. As was the case when Ms. C initially took a combined contraceptive, hormonal contraceptives can sometimes cause mood dysregulation.

Continue to: OUTCOME Improved symptoms

OUTCOME Improved symptoms

Ms. C meets with her gynecologist, who prescribes norethindrone, a progestin-only oral contraceptive. Since taking norethindrone, Ms. C reports a dramatic improvement in the mood symptoms she experiences during the postmenstrual period.

Bottom Line

Some women may experience mood symptoms during the postmenstrual period that are similar to the symptoms experienced by patients who have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). This phenomenon has been described as postmenstrual syndrome, and though evidence is lacking, treating it similarly to PMDD may be effective.

Related Resources

- Ray P, Mandal N, Sinha VK. Change of symptoms of schizophrenia across phases of menstrual cycle. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s00737-019-0952-4

- Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

Drug Brand Names

Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol • Yasmin

Dutasteride • Avodart

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Progesterone • Prometrium

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Increased anxiety and depression

Ms. C, age 29, has bipolar II disorder (BD II) and generalized anxiety disorder. She presents to her outpatient psychiatrist seeking relief from chronic and significant dips in her mood from Day 5 to Day 15 of her menstrual cycle. During this time, she says she experiences increased anxiety, insomnia, frequent tearfulness, and intermittent suicidal ideation.

Ms. C meticulously charts her menstrual cycle using a smartphone app and reports having a regular 28-day cycle. She says she has experienced this worsening of symptoms since the onset of menarche, but her mood generally stabilizes after Day 14 of her cycle–around the time of ovulation–and remains euthymic throughout the premenstrual period.

HISTORY Depression and a change in medication

Ms. C has a history of major depressive episodes and has experienced hypomanic episodes that lasted 1 to 2 weeks and were associated with an elevated mood, high energy, rapid speech, and increased self-confidence. Ms. C says she has chronically high anxiety associated with trouble sleeping, difficulty focusing, restlessness, and muscle tension. When she was receiving care from previous psychiatrists, treatment with lithium, quetiapine, lamotrigine, sertraline, and fluoxetine was not successful, and Ms. C said she had severe anxiety when she tried sertraline and fluoxetine. After several months of substantial mood instability and high anxiety, Ms. C responded well to pregabalin 100 mg 3 times a day, lurasidone 60 mg/d at bedtime, and gabapentin 500 mg/d at bedtime. Over the last 4 months, she reports that her overall mood has been even, and she has been coping well with her anxiety.

Ms. C is married with no children. She uses condoms for birth control. She previously tried taking a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive, but stopped because she said it made her feel very depressed. Ms. C reports no history of substance use. She is employed, says she has many positive relationships, and does not have a social history suggestive of a personality disorder.

[polldaddy:11818926]

The author’s observations

Many women report worsening of mood during the premenstrual period (luteal phase). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) involves symptoms that develop during the luteal phase and end shortly after menstruation; this condition impacts ≤5% of women.1 The etiology of PMDD appears to involve contributions from genetics, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite), brain-derived neurotrophic factor, brain structural and functional differences, and hypothalamic pathways.2

Researchers have postulated that the precipitous decline in the levels of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the luteal phase may contribute to the mood symptoms of PMDD.2 Allopregnanolone is a modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors and may exert anxiolytic and sedative effects. Women who experience PMDD may be less sensitive to the effects of allopregnanolone.3 Additionally, early luteal phase levels of estrogen may predict late luteal phase symptoms of PMDD.4 The mechanism involved may be estrogen’s effect on the serotonin system. The HPA axis may also be involved in the etiology of PMDD because patients with this condition appear to have a blunted cortisol response in reaction to stress.5 Research also has implicated immune activation and inflammation in the etiology of PMDD.6

A PMDD diagnosis should be distinguished from a premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric condition, which occurs when a patient has an untreated primary mood or anxiety disorder that worsens during the premenstrual period. PMDD is differentiated from premenstrual syndrome by the severity of symptoms.2 The recommended first-line treatment of PMDD is an SSRI, but if an SSRI does not work, is not tolerated, or is not preferred for any other reason, recommended alternatives include combined hormone oral contraceptive pills, dutasteride, gabapentin, or various supplements.7,8 PMDD has been widely studied and is treated by both psychiatrists and gynecologists. In addition, some women report experiencing mood instability around ovulation. Kiesner9 found that 13% of women studied showed an increased negative mood state midcycle, rather than during the premenstrual period.

Continue to: Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual mood symptoms are atypical. Postmenstrual syndrome is not listed in DSM-5 or formally recognized as a medical diagnosis. Peer-reviewed research or literature on the condition is scarce to nonexistent. However, it has been discussed by physicians in articles in the lay press. One gynecologist and reproductive endocrinologist estimated that approximately 10% of women experience significant physical and emotional symptoms postmenstruation.10 An internist and women’s health specialist suggested that the cause of postmenstrual syndrome might be a surge in levels of estrogen and testosterone and may be associated with insulin resistance and polycystic ovarian syndrome, while another possible contribution could be iron deficiency caused by loss of blood from menstruation.11

TREATMENT Recommending an oral contraceptive

Ms. C’s psychiatrist does not prescribe an SSRI because he is concerned it would destabilize her BD II. The patient also had negative experiences in her past 2 trials of SSRIs.

Because the psychiatrist believes it is prudent to optimize the dosages of a patient’s current medication before starting a new medication or intervention, he considers increasing Ms. C’s dosage of lurasidone or pregabalin. The rationale for optimizing Ms. C’s current medication regimen is that greater overall mood stability would likely result in less severe postmenstrual mood symptoms. However, Ms. C does not want to increase her dosage of either medication because she is concerned about adverse effects.

Ms. C’s psychiatrist discusses the case with 2 gynecologist/obstetrician colleagues. One suggests the patient try a progesterone-only oral contraceptive and the other suggests a trial of Prometrium (a progesterone capsule used to treat endometrial hyperplasia and secondary amenorrhea). Both suggestions are based on the theory that Ms. C may be sensitive to levels of progesterone, which are low during the follicular phase and rise after ovulation; neither recommendation is evidence-based. A low level of allopregnanolone may lead to less GABAergic activity and consequently greater mood dysregulation. Some women are particularly sensitive to low levels of allopregnanolone in the follicular phase, which might lead to postmenstrual mood symptoms. Additionally, Ms. C’s previous treatment with a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive may have decreased her level of allopregnanolone.12 Ultimately, Ms. C’s psychiatrist suggests that she take a progesterone-only oral contraceptive.

The author’s observations

Guidance on how to treat Ms. C’s postmenstrual symptoms came from research on how to treat PMDD in patients who have BD. In a review of managing PMDD in women with BD, Sepede et al13 presented a treatment algorithm that recommends a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive as first-line treatment in euthymic patients who are already receiving an optimal dose of mood stabilizers. Sepede et al13 expressed caution about using SSRIs due to the risk of inducing mood changes, but recommended SSRIs for patients with comorbid PMDD and BD who experience a depressive episode.

Another question is which type of oral contraceptive is most effective for treating PMDD. The combined oral contraceptive drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol has the most evidence for efficacy.14 Combined oral contraceptives carry risks of venous thromboembolism, hypertension, stroke, migraines, and liver complications, and are possibly associated with certain types of cancer, such as breast and cervical cancer.15 Their use is contraindicated in patients with a history of these conditions and for women age >35 who smoke ≥15 cigarettes/d.

The limited research that has examined the efficacy of progestin-only oral contraceptives for treating PMDD has been inconclusive.16 However, progesterone-only oral contraceptives are associated with less overall risk than combined oral contraceptives, and many women opt to use progesterone-only oral contraceptives due to concerns about possible adverse effects of the combined formulations. A substantial drawback of progesterone-only oral contraceptives is they must be taken at the same time every day, and if a dose is taken late, these agents may lose their efficacy in preventing pregnancy (and a backup birth control method must be used17). Additionally, drospirenone, a progestin that is a component of many oral contraceptives, has antimineralocorticoid properties and is contraindicated in patients with kidney or adrenal gland insufficiency or liver disease. As was the case when Ms. C initially took a combined contraceptive, hormonal contraceptives can sometimes cause mood dysregulation.

Continue to: OUTCOME Improved symptoms

OUTCOME Improved symptoms

Ms. C meets with her gynecologist, who prescribes norethindrone, a progestin-only oral contraceptive. Since taking norethindrone, Ms. C reports a dramatic improvement in the mood symptoms she experiences during the postmenstrual period.

Bottom Line

Some women may experience mood symptoms during the postmenstrual period that are similar to the symptoms experienced by patients who have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). This phenomenon has been described as postmenstrual syndrome, and though evidence is lacking, treating it similarly to PMDD may be effective.

Related Resources

- Ray P, Mandal N, Sinha VK. Change of symptoms of schizophrenia across phases of menstrual cycle. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s00737-019-0952-4

- Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

Drug Brand Names

Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol • Yasmin

Dutasteride • Avodart

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Progesterone • Prometrium

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

2. Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

3. Timby E, Bäckström T, Nyberg S, et al. Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have altered sensitivity to allopregnanolone over the menstrual cycle compared to controls--a pilot study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(11):2109-2117.

4. Yen JY, Lin HC, Lin PC, et al. Early- and late-luteal-phase estrogen and progesterone levels of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4352.

5. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

6. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

7. Tiranini L, Nappi RE. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Rev. 2022:11:(11). doi:10.12703/r/11-11

8. Raffi ER. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/145089/somatic-disorders/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder

9. Kiesner J. One woman’s low is another woman’s high: paradoxical effects of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(1):68-76.

10. Alnuweiri T. Feel low after your period? Postmenstrual syndrome could be the reason. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.wellandgood.com/pms-after-period/

11. Sharkey L. Everything you need to know about post-menstrual syndrome. Healthline. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.healthline.com/health/post-menstrual-syndrome

12. Santoru F, Berretti R, Locci A, et al. Decreased allopregnanolone induced by hormonal contraceptives is associated with a reduction in social behavior and sexual motivation in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3351-3364.

13. Sepede G, Brunetti M, Di Giannantonio M. Comorbid premenstrual dysphoric disorder in women with bipolar disorder: management challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2020;16:415-426.

14. Rapkin AJ, Korotkaya Y, Taylor KC. Contraception counseling for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): current perspectives. Open Access J Contraception. 2019;10:27-39. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S183193

15. Roe AH, Bartz DA, Douglas PS. Combined estrogen-progestin contraception: side effects and health concerns. UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/combined-estrogen-progestin-contraception-side-effects-and-health-concerns

16. Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, et al. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2012;3:CD003415. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4

17. Kaunitz AM. Contraception: progestin-only pills (POPs). UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/contraception-progestin-only-pills-pops

1. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

2. Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

3. Timby E, Bäckström T, Nyberg S, et al. Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have altered sensitivity to allopregnanolone over the menstrual cycle compared to controls--a pilot study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(11):2109-2117.

4. Yen JY, Lin HC, Lin PC, et al. Early- and late-luteal-phase estrogen and progesterone levels of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4352.

5. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

6. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

7. Tiranini L, Nappi RE. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Rev. 2022:11:(11). doi:10.12703/r/11-11

8. Raffi ER. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/145089/somatic-disorders/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder

9. Kiesner J. One woman’s low is another woman’s high: paradoxical effects of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(1):68-76.

10. Alnuweiri T. Feel low after your period? Postmenstrual syndrome could be the reason. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.wellandgood.com/pms-after-period/

11. Sharkey L. Everything you need to know about post-menstrual syndrome. Healthline. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.healthline.com/health/post-menstrual-syndrome

12. Santoru F, Berretti R, Locci A, et al. Decreased allopregnanolone induced by hormonal contraceptives is associated with a reduction in social behavior and sexual motivation in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3351-3364.

13. Sepede G, Brunetti M, Di Giannantonio M. Comorbid premenstrual dysphoric disorder in women with bipolar disorder: management challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2020;16:415-426.

14. Rapkin AJ, Korotkaya Y, Taylor KC. Contraception counseling for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): current perspectives. Open Access J Contraception. 2019;10:27-39. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S183193

15. Roe AH, Bartz DA, Douglas PS. Combined estrogen-progestin contraception: side effects and health concerns. UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/combined-estrogen-progestin-contraception-side-effects-and-health-concerns

16. Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, et al. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2012;3:CD003415. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4

17. Kaunitz AM. Contraception: progestin-only pills (POPs). UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/contraception-progestin-only-pills-pops

Proposal for a new diagnosis: Acute anxiety disorder

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

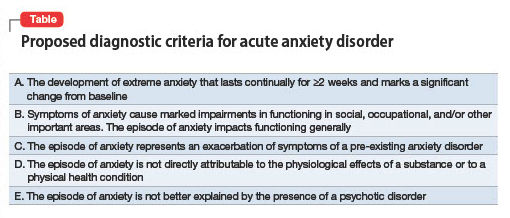

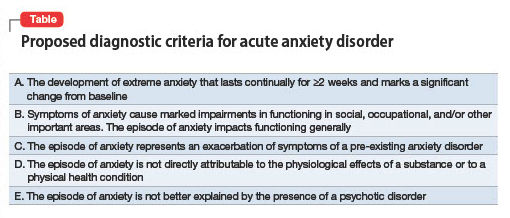

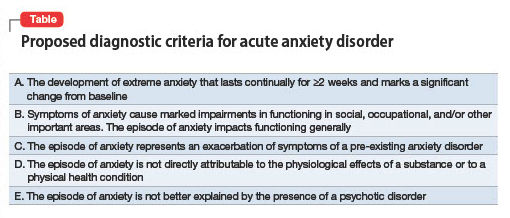

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. F, age 42, says he has always been a very anxious person and has chronically found his worrying to negatively affect his life. He says that over the last month his anxiety has been “off the charts” and he is worrying “24/7” due to taking on new responsibilities at his job and his son being diagnosed with lupus. He says his constant worrying is significantly impairing his ability to focus at his job, and he is considering taking a mental health leave from work. His wife reports that she is extremely frustrated because Mr. F has been isolating himself from family and friends; he admits this is true and attributes it to being preoccupied by his worries.

Mr. F endorses chronic insomnia, muscle tension, and irritability associated with anxiety; these have all substantially worsened over the last month. He admits that recently he has occasionally thought it would be easier if he weren’t alive. Mr. F denies having problems with his energy or motivation levels and insists that he generally feels very anxious, but not depressed. He says he drinks 1 alcoholic drink per week and denies any other substance use. Mr. F is overweight and has slightly elevated cholesterol but denies any other health conditions. He takes melatonin to help him sleep but does not take any prescribed medications.

Although this vignette provides limited details, on the surface it appears that Mr. F is experiencing an exacerbation of chronic generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). However, in this article, I propose establishing a new diagnosis: “acute anxiety disorder,” which would encapsulate severe exacerbations of a pre-existing anxiety disorder. Among the patients I have encountered for whom this diagnosis would fit, most have pre-existing GAD or panic disorder.

A look at the differential diagnosis

It is important to determine whether Mr. F is using any substances or has a medical condition that could be contributing to his anxiety. Other psychiatric diagnoses that could be considered include:

Adjustment disorder. This diagnosis would make sense if Mr. F didn’t have an apparent chronic history of symptoms that meet criteria for GAD.

Major depressive disorder with anxious distress. Many patients experiencing a major depressive episode meet the criteria for the specifier “with anxious distress,” even those who do not have a comorbid anxiety disorder.1 However, it is not evident from this vignette that Mr. F is experiencing a major depressive episode.

Continue to: Panic disorder and GAD...

Panic disorder and GAD. It is possible for a patient with GAD to develop panic disorder, which, at times, occurs after experiencing significant life stressors. Panic disorder requires the presence of recurrent panic attacks. Mr. F describes experiencing chronic, intense symptoms of anxiety rather than the discreet episodes of acute symptoms that characterize panic attacks.

Acute stress disorder. This diagnosis involves psychological symptoms that occur in response to exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation. Mr. F was not exposed to any of these stressors.

Why this new diagnosis would be helpful

A new diagnosis, acute anxiety disorder, would indicate that a patient is currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of a chronic anxiety disorder that is leading to a significant decrease in their baseline functioning. My proposed criteria for acute anxiety disorder appear in the Table. Here are some reasons this diagnosis would be helpful:

Signifier of severity. Anxiety disorders such as GAD are generally not considered severe conditions and not considered to fall under the rubric of SPMI (severe and persistent mental illness).2 Posttraumatic stress disorder is the anxiety disorder–like condition most often found in the SPMI category. A diagnosis of acute anxiety disorder would indicate a patient is experiencing an episode of anxiety that is distinct from their chronic anxiety condition due to its severe impact on functional capabilities. Acute anxiety disorder would certainly not qualify as a “SPMI diagnosis” that would facilitate someone being considered eligible for supplemental security income, but it might be a legitimate justification for someone to receive short-term disability.

Treatment approach. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders usually involves a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). However, these medications can sometimes briefly increase anxiety when they are started. Individuals with acute anxiety are the most vulnerable to the possibility of experiencing increased anxiety when starting an SSRI or SNRI and may benefit from a slower titration of these medications. In light of this and the length of time required for SSRIs or SNRIs to exert a positive effect (typically a few weeks), patients with acute anxiety are best served by treatment with a medication with an immediate onset of action, such as a benzodiazepine or a sleep medication (eg, zolpidem). Benzodiazepines and hypnotics such as zolpidem are best prescribed for as-needed use because they carry a risk of dependence. One might consider prescribing mirtazapine or pregabalin (both of which are used off-label to treat anxiety) because these medications also have a relatively rapid onset of action and can treat both anxiety and insomnia (particularly mirtazapine).

Research considerations. It would be helpful to study which treatments are most effective for the subset of patients who experience acute anxiety disorder as I define it. Perhaps psychotherapy treatment protocols could be adapted or created. Treatment with esketamine or IV ketamine might be further studied as a treatment for acute anxiety because some evidence suggests ketamine is efficacious for this indication.3

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073

1. Otsubo T, Hokama C, Sano N, et al. How significant is the assessment of the DSM-5 ‘anxious distress’ specifier in patients with major depressive disorder without comorbid anxiety disorders in the continuation/maintenance phase? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(4):385-392. doi:10.1080/13651501.2021.1907415

2. Butler H, O’Brien AJ. Access to specialist palliative care services by people with severe and persistent mental illness: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(2):737-746. doi:10.1111/inm.12360

3. Glue P, Neehoff SM, Medlicott NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of maintenance ketamine treatment in patients with treatment-refractory generalised anxiety and social anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(6):663-667. doi:10.1177/0269881118762073