User login

The 'Nuts and Bolts' of Drug Concentration Monitoring in IBD

Introduction

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy is the cornerstone of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment.1 Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients show no clinical benefit, considered as primary non-responders, while another 50% lose response over time and need to escalate or discontinue anti-TNF therapy due to either pharmacokinetic (PK) or pharmacodynamic issues.2 Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), defined as the assessment of drug concentration and anti-drug antibodies (ADA), is emerging as a new therapeutic strategy to better explain, manage, and hopefully prevent these undesired clinical outcomes.3 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that higher serum anti-TNF drug concentrations both during maintenance and induction therapy are associated with favorable objective therapeutic outcomes, suggesting of a ‘treat-to-trough’ in addition to a ‘treat-to-target’ therapeutic approach.4-6 This concept of TDM is not new in IBD. TDM has also been used for optimizing thiopurines.7 This brief review will discuss a practical approach to the use of TDM in IBD with a focus on its use with anti-TNF therapies.

Reactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

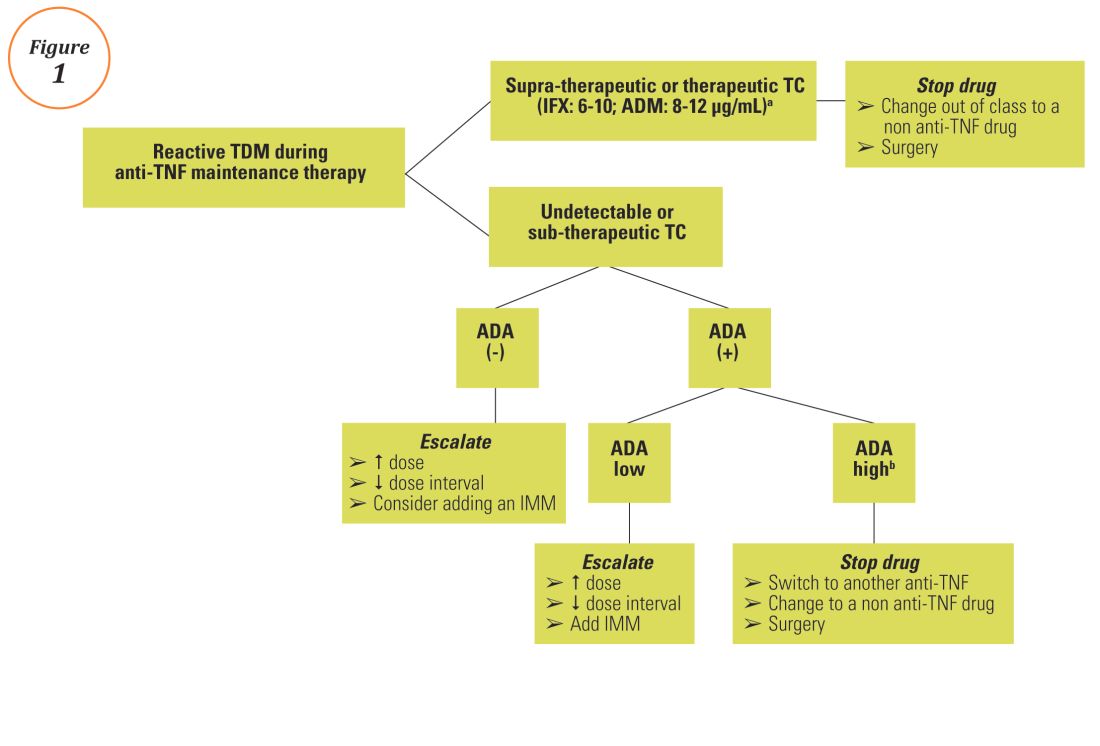

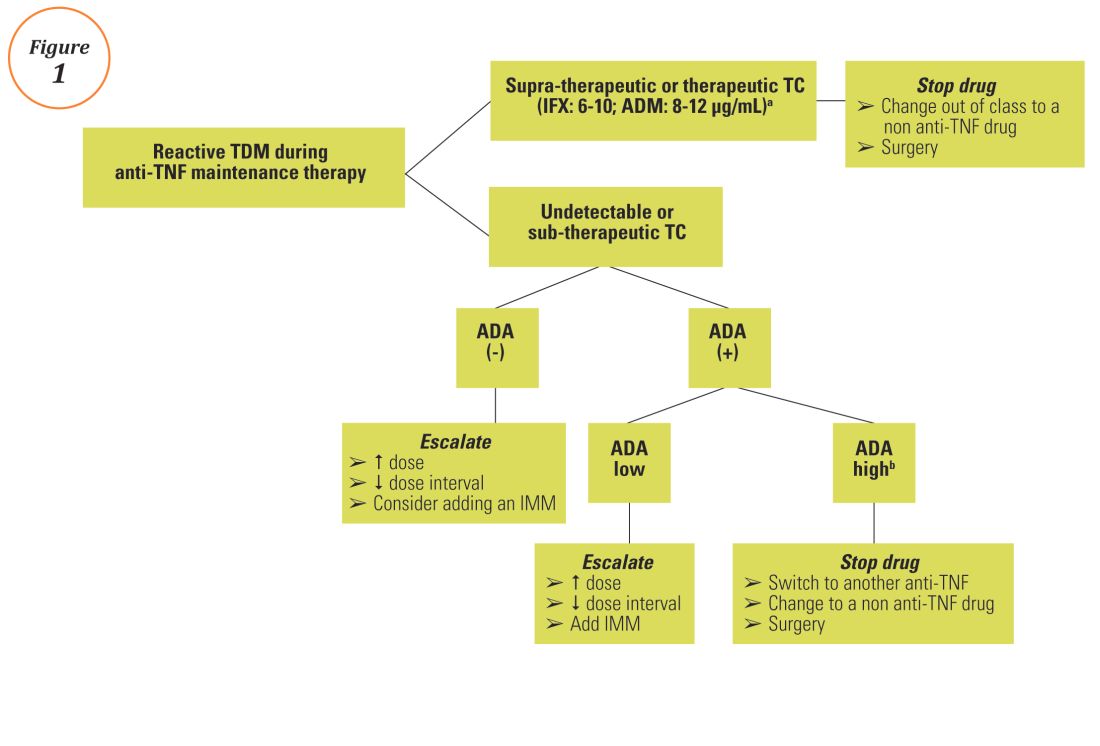

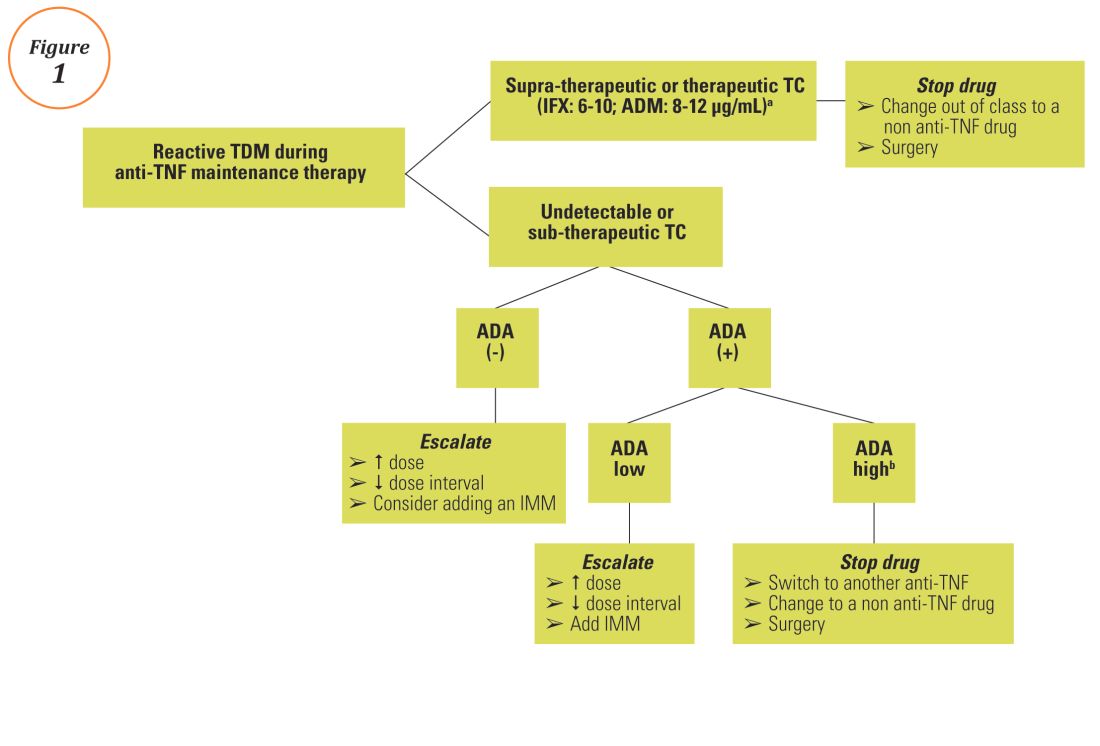

Reactive TDM more rationally guides therapeutic decisions for dealing with loss of response to anti-TNF therapy in IBD and is actually more cost-effective.8,9 Patients with sub-therapeutic or undetectable drug concentrations without ADA derive more benefit from dose escalation (increasing the dose or decreasing the interval) compared to those switched to another anti-TNF agent. On the other hand, patients with therapeutic or supra-therapeutic drug concentrations have better outcomes when changing to a medication with a different mechanism of action (as their disease is probably no longer TNF-driven).3 A recent study showed that trough concentration of adalimumab >4.5 mcg/mL or infliximab >3.8 mcg/mL at time of loss of response identifies patients who benefit more from alternative therapies rather than dose escalation or switching to another anti-TNF agent.10 In clinical practice, in order to fully optimize the original anti-TNF, we will typically dose optimize patients to drug concentrations of infliximab and adalimumab to >10 mcg/mL before giving up and changing medications. Moreover, patients with high ADA titer have better outcomes when switched to another anti-TNF rather than undergo further dose escalation.3 Vande Casteele et al, showed that antibodies to infliximab (ATI) >9.1 U/mL at time of loss of response resulted in a likelihood ratio of 3.6 for an unsuccessful intervention, defined as the need to initiate corticosteroids, immunomodulators (IMM), or other medications or infliximab discontinuation within two infusions after the intervention (shorten of infusion intervals, dose increase to 10 mg/kg, or a combination of both).11 A proposed treatment algorithm for using reactive TDM for anti-TNF therapy is shown in Figure 1.

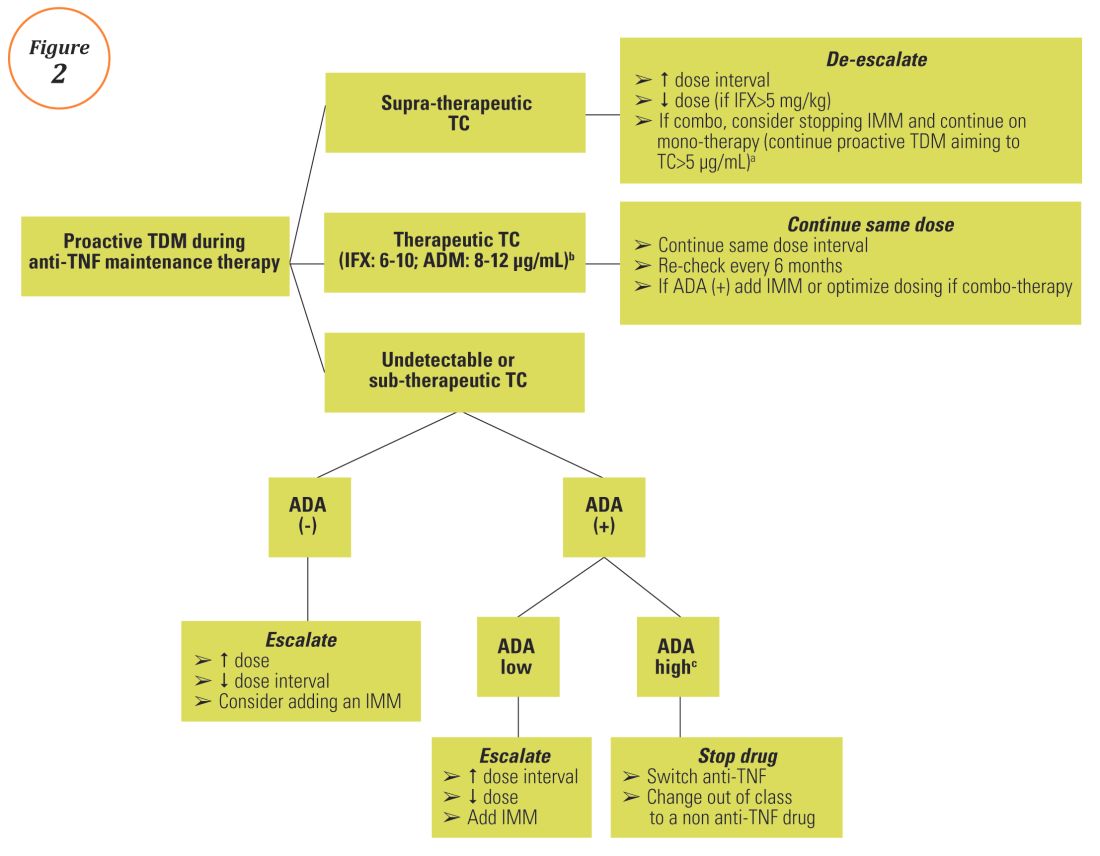

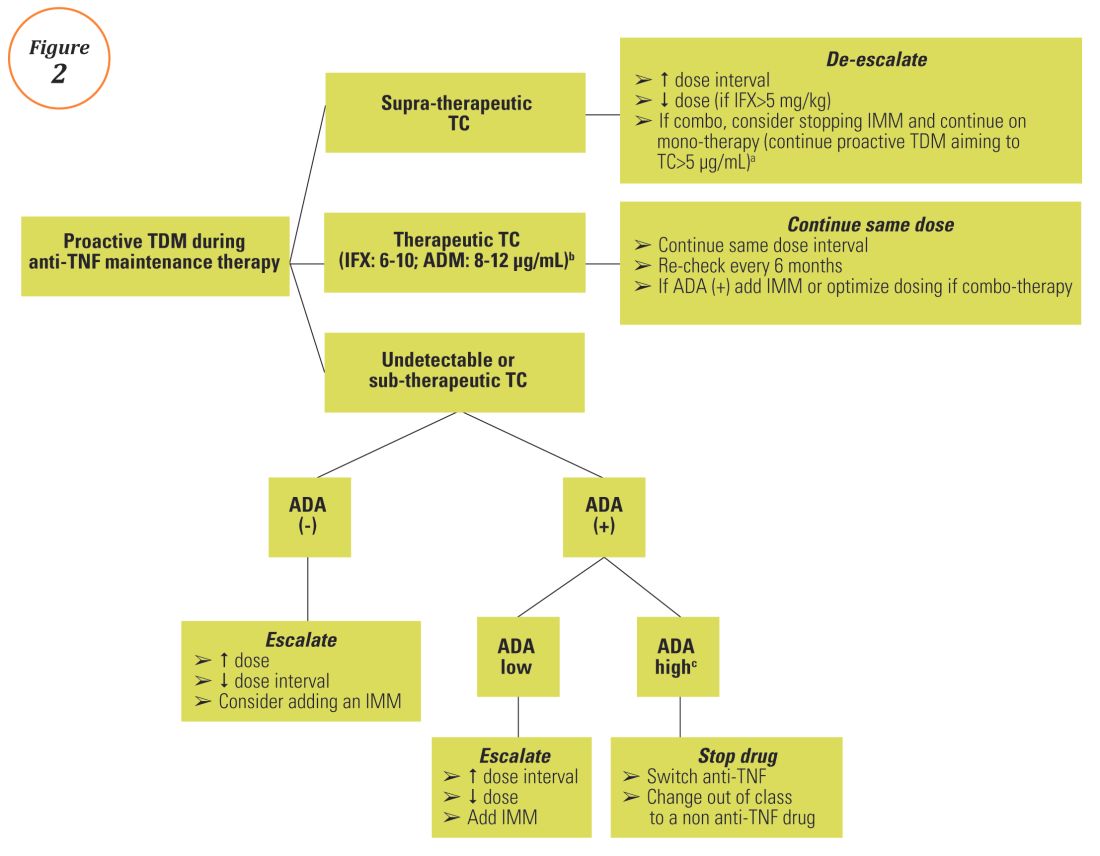

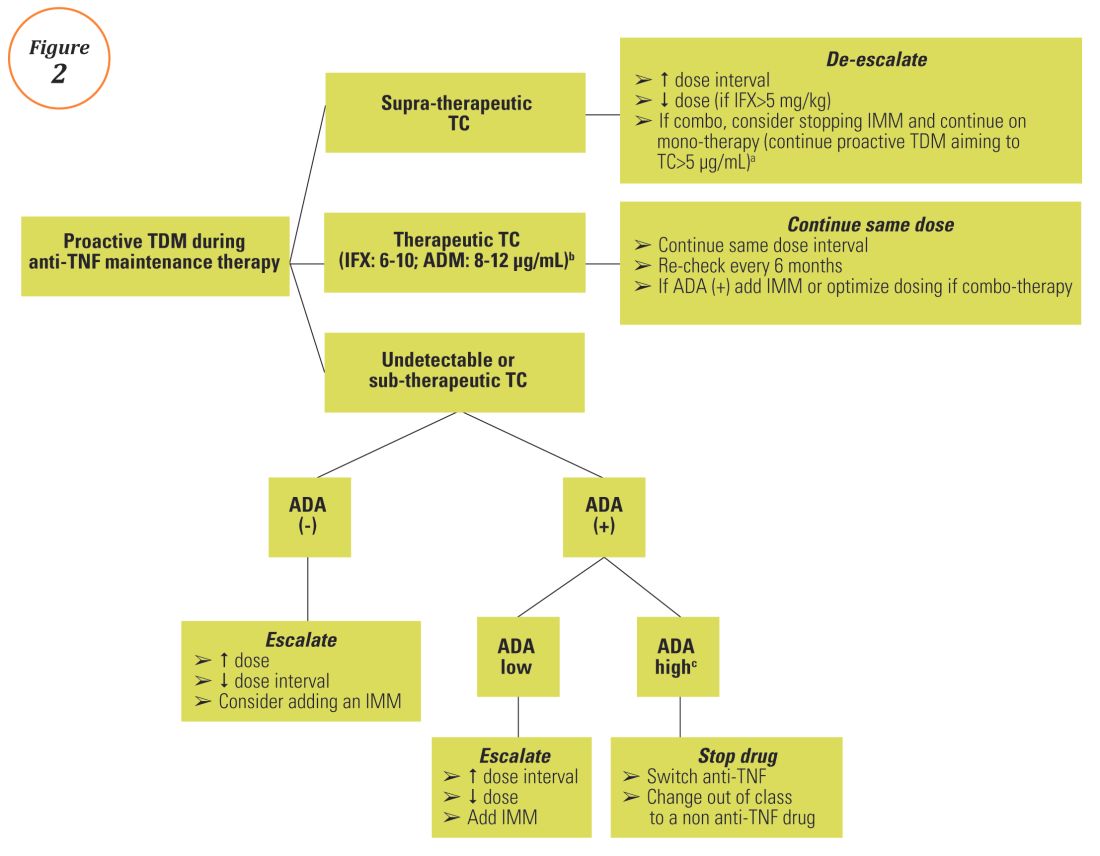

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

TDM of thiopurines

Anti-TNF TDM assays

Conclusions

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the clinical utility of TDM of anti-TNF therapy in IBD clinical practice and a move towards personalized medicine, as it is now clear that “one dose does not fit all patients.” Nevertheless, before a TDM-based approach can be widely implemented and emerge as the new standard-of-care for anti-TNF therapy in IBD, several barriers regarding cost issues (insurance coverage and out of pocket expenses), time lag from serum sampling to test results (typically 5 to 10 days), proper interpretation and application of the results, type of assay used, and the optimal timing of serum collection should be overcome. Initiatives are already underway including the development of accurate, easily accessible, and affordable rapid assays that will allow anti-TNF concentration measurement at the point-of-care site and software-decision support tools or ‘dashboards’ that will incorporate a predictive PK model based on patient and disease characteristics.29,30 Additionally, more data from well-designed prospective studies and randomized controlled trials regarding both induction and maintenance treatment and for all available biologics (originators and biosimilars) are urgently needed. A panel consisting of members of the Building Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Globally research alliance (www.BRIDGeIBD.com), and recognized leaders in the field of TDM in IBD has recently published recommendations that help clinicians on the appropriate timing and best way to interpret and respond to TDM results depending on the specific clinical scenario.31

Funding: KP received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD.

Potential competing interests: K.P.: nothing to disclose; A.S.C: received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

Dr. Papamichail is a research fellow and Dr. Cheifetz is the director of the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, division of gastroenterology, Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Papamichail received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD. Dr. Cheifetz received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

References

1. Miligkos M, Papamichael K, Casteele NV, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha versus anti-integrin agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a network meta-analysis of indirect comparisons. Clin Ther. 2016;38(6):1342-1358.e6

2. Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):182-97

3. Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Use of anti-TNF drug levels to optimise patient management. Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7;289-300.

4. Papamichael K, Baert F, Tops S, et al. Post-Induction Adalimumab concentration is associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:53-59

5. Papamichael K, Van Stappen T, Vande Casteele N, et al. Infliximab concentration thresholds during induction therapy are associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:543-9.

6. Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing Anti-TNF-Alpha Therapy: Serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:550-557.e2.

7. Singh N, Dubinsky MC. Therapeutic drug monitoring in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a practical approach. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11:48-55.

8. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut 2014;63:919-27.

9. Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, et al. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:654–66.

10. Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:522-30.

11. Casteele NV, Gils A, Singh S, et al. Antibody response to infliximab and its impact on pharmacokinetics can be transient. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:962-71.

12. Vaughn BP, Martinez-Vazquez M, Patwardhan VR, et al. Proactive therapeutic concentration monitoring of infliximab may improve outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a pilot observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1996-2003.

13. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1320-9.e3.

14. Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1296–307.e5.

15. Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, et al. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014;63:1721–7.

16. Arias MT, Vande Casteele N, Vermeire S, et al. A panel to predict long-term outcome of infliximab therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:531–8.

17. Singh N, Rosenthal CJ, Melmed GY, et al Early infliximab trough levels are associated with persistent remission in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1708-13.

18. Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1324–32.

19. Baert F, Kondragunta V, Lockton S, et al. Antibodies to adalimumab are associated with future inflammation in Crohn’s patients receiving maintenance adalimumab therapy: a post hoc analysis of the Karmiris trial. Gut 2016;65:1126–31.

20. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Allez M, et al. Association between plasma concentrations of certolizumab pegol and endoscopic outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:423-31.e1

21. Pariente B, Laharie D. Review article: why, when and how to de-escalate therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:338–53.

22. Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, et al. Early trough levels and antibodies to infliximab predict safety and success of reinitiation of infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1474-81.e2

23. Osterman MT, Kundu R, Lichtenstein GR, Lewis JD. Association of 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and inflammatory bowel disease activity: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1047-53

24. Dassopoulos T, Dubinsky MC, Bentsen JL, et al. Randomised clinical trial: individualised vs. weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:163-175.

25. Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wang S, et al. Algorithms outperform metabolite tests in predicting response of patients with inflammatory bowel disease to thiopurines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:143-150.

26. Yarur A, Kubiliun M, Czul F, et al. Concentrations of 6-thioguanine nucleotide correlate with trough levels of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on combination therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1118-1124.

27. Marini JC, Sendecki J, Cornillie F, et al. Comparisons of serum infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab tests used in inflammatory bowel disease clinical trials of Remicade®.AAPS J. 2016 Sep 6. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1208/s12248-016-9981-3

28. Gils A, Vande Casteele N, Poppe R, et al. Development of a universal anti-adalimumab antibody standard for interlaboratory harmonization. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36:669-673.

29. Van Stappen T, Bollen L, Vande Casteele N, et al. Rapid test for infliximab drug concentration allows immediate dose adaptation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7:e206

30. Dubinsky MC, Phan BL, Singh N, et al. Pharmacokinetic dashboard-recommended dosing is different than standard of care dosing in infliximab-treated pediatric IBD patients. AAPS J. 2016 Oct 13. [Epub ahead of print]

31. Melmed GY, Irving PM, Jones J, et al. Appropriateness of testing for anti-tumor necrosis factor agent and antibody concentrations, and interpretation of results. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1302-9.

32. Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:601-8.

33. Drobne D, Bossuyt P, Breynaert C, et al. Withdrawal of immunomodulators after co-treatment does not reduce trough level of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:514-21.e4.

Introduction

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy is the cornerstone of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment.1 Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients show no clinical benefit, considered as primary non-responders, while another 50% lose response over time and need to escalate or discontinue anti-TNF therapy due to either pharmacokinetic (PK) or pharmacodynamic issues.2 Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), defined as the assessment of drug concentration and anti-drug antibodies (ADA), is emerging as a new therapeutic strategy to better explain, manage, and hopefully prevent these undesired clinical outcomes.3 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that higher serum anti-TNF drug concentrations both during maintenance and induction therapy are associated with favorable objective therapeutic outcomes, suggesting of a ‘treat-to-trough’ in addition to a ‘treat-to-target’ therapeutic approach.4-6 This concept of TDM is not new in IBD. TDM has also been used for optimizing thiopurines.7 This brief review will discuss a practical approach to the use of TDM in IBD with a focus on its use with anti-TNF therapies.

Reactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

Reactive TDM more rationally guides therapeutic decisions for dealing with loss of response to anti-TNF therapy in IBD and is actually more cost-effective.8,9 Patients with sub-therapeutic or undetectable drug concentrations without ADA derive more benefit from dose escalation (increasing the dose or decreasing the interval) compared to those switched to another anti-TNF agent. On the other hand, patients with therapeutic or supra-therapeutic drug concentrations have better outcomes when changing to a medication with a different mechanism of action (as their disease is probably no longer TNF-driven).3 A recent study showed that trough concentration of adalimumab >4.5 mcg/mL or infliximab >3.8 mcg/mL at time of loss of response identifies patients who benefit more from alternative therapies rather than dose escalation or switching to another anti-TNF agent.10 In clinical practice, in order to fully optimize the original anti-TNF, we will typically dose optimize patients to drug concentrations of infliximab and adalimumab to >10 mcg/mL before giving up and changing medications. Moreover, patients with high ADA titer have better outcomes when switched to another anti-TNF rather than undergo further dose escalation.3 Vande Casteele et al, showed that antibodies to infliximab (ATI) >9.1 U/mL at time of loss of response resulted in a likelihood ratio of 3.6 for an unsuccessful intervention, defined as the need to initiate corticosteroids, immunomodulators (IMM), or other medications or infliximab discontinuation within two infusions after the intervention (shorten of infusion intervals, dose increase to 10 mg/kg, or a combination of both).11 A proposed treatment algorithm for using reactive TDM for anti-TNF therapy is shown in Figure 1.

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

TDM of thiopurines

Anti-TNF TDM assays

Conclusions

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the clinical utility of TDM of anti-TNF therapy in IBD clinical practice and a move towards personalized medicine, as it is now clear that “one dose does not fit all patients.” Nevertheless, before a TDM-based approach can be widely implemented and emerge as the new standard-of-care for anti-TNF therapy in IBD, several barriers regarding cost issues (insurance coverage and out of pocket expenses), time lag from serum sampling to test results (typically 5 to 10 days), proper interpretation and application of the results, type of assay used, and the optimal timing of serum collection should be overcome. Initiatives are already underway including the development of accurate, easily accessible, and affordable rapid assays that will allow anti-TNF concentration measurement at the point-of-care site and software-decision support tools or ‘dashboards’ that will incorporate a predictive PK model based on patient and disease characteristics.29,30 Additionally, more data from well-designed prospective studies and randomized controlled trials regarding both induction and maintenance treatment and for all available biologics (originators and biosimilars) are urgently needed. A panel consisting of members of the Building Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Globally research alliance (www.BRIDGeIBD.com), and recognized leaders in the field of TDM in IBD has recently published recommendations that help clinicians on the appropriate timing and best way to interpret and respond to TDM results depending on the specific clinical scenario.31

Funding: KP received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD.

Potential competing interests: K.P.: nothing to disclose; A.S.C: received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

Dr. Papamichail is a research fellow and Dr. Cheifetz is the director of the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, division of gastroenterology, Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Papamichail received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD. Dr. Cheifetz received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

References

1. Miligkos M, Papamichael K, Casteele NV, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha versus anti-integrin agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a network meta-analysis of indirect comparisons. Clin Ther. 2016;38(6):1342-1358.e6

2. Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):182-97

3. Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Use of anti-TNF drug levels to optimise patient management. Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7;289-300.

4. Papamichael K, Baert F, Tops S, et al. Post-Induction Adalimumab concentration is associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:53-59

5. Papamichael K, Van Stappen T, Vande Casteele N, et al. Infliximab concentration thresholds during induction therapy are associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:543-9.

6. Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing Anti-TNF-Alpha Therapy: Serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:550-557.e2.

7. Singh N, Dubinsky MC. Therapeutic drug monitoring in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a practical approach. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11:48-55.

8. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut 2014;63:919-27.

9. Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, et al. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:654–66.

10. Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:522-30.

11. Casteele NV, Gils A, Singh S, et al. Antibody response to infliximab and its impact on pharmacokinetics can be transient. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:962-71.

12. Vaughn BP, Martinez-Vazquez M, Patwardhan VR, et al. Proactive therapeutic concentration monitoring of infliximab may improve outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a pilot observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1996-2003.

13. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1320-9.e3.

14. Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1296–307.e5.

15. Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, et al. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014;63:1721–7.

16. Arias MT, Vande Casteele N, Vermeire S, et al. A panel to predict long-term outcome of infliximab therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:531–8.

17. Singh N, Rosenthal CJ, Melmed GY, et al Early infliximab trough levels are associated with persistent remission in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1708-13.

18. Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1324–32.

19. Baert F, Kondragunta V, Lockton S, et al. Antibodies to adalimumab are associated with future inflammation in Crohn’s patients receiving maintenance adalimumab therapy: a post hoc analysis of the Karmiris trial. Gut 2016;65:1126–31.

20. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Allez M, et al. Association between plasma concentrations of certolizumab pegol and endoscopic outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:423-31.e1

21. Pariente B, Laharie D. Review article: why, when and how to de-escalate therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:338–53.

22. Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, et al. Early trough levels and antibodies to infliximab predict safety and success of reinitiation of infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1474-81.e2

23. Osterman MT, Kundu R, Lichtenstein GR, Lewis JD. Association of 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and inflammatory bowel disease activity: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1047-53

24. Dassopoulos T, Dubinsky MC, Bentsen JL, et al. Randomised clinical trial: individualised vs. weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:163-175.

25. Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wang S, et al. Algorithms outperform metabolite tests in predicting response of patients with inflammatory bowel disease to thiopurines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:143-150.

26. Yarur A, Kubiliun M, Czul F, et al. Concentrations of 6-thioguanine nucleotide correlate with trough levels of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on combination therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1118-1124.

27. Marini JC, Sendecki J, Cornillie F, et al. Comparisons of serum infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab tests used in inflammatory bowel disease clinical trials of Remicade®.AAPS J. 2016 Sep 6. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1208/s12248-016-9981-3

28. Gils A, Vande Casteele N, Poppe R, et al. Development of a universal anti-adalimumab antibody standard for interlaboratory harmonization. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36:669-673.

29. Van Stappen T, Bollen L, Vande Casteele N, et al. Rapid test for infliximab drug concentration allows immediate dose adaptation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7:e206

30. Dubinsky MC, Phan BL, Singh N, et al. Pharmacokinetic dashboard-recommended dosing is different than standard of care dosing in infliximab-treated pediatric IBD patients. AAPS J. 2016 Oct 13. [Epub ahead of print]

31. Melmed GY, Irving PM, Jones J, et al. Appropriateness of testing for anti-tumor necrosis factor agent and antibody concentrations, and interpretation of results. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1302-9.

32. Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:601-8.

33. Drobne D, Bossuyt P, Breynaert C, et al. Withdrawal of immunomodulators after co-treatment does not reduce trough level of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:514-21.e4.

Introduction

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy is the cornerstone of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment.1 Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients show no clinical benefit, considered as primary non-responders, while another 50% lose response over time and need to escalate or discontinue anti-TNF therapy due to either pharmacokinetic (PK) or pharmacodynamic issues.2 Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), defined as the assessment of drug concentration and anti-drug antibodies (ADA), is emerging as a new therapeutic strategy to better explain, manage, and hopefully prevent these undesired clinical outcomes.3 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that higher serum anti-TNF drug concentrations both during maintenance and induction therapy are associated with favorable objective therapeutic outcomes, suggesting of a ‘treat-to-trough’ in addition to a ‘treat-to-target’ therapeutic approach.4-6 This concept of TDM is not new in IBD. TDM has also been used for optimizing thiopurines.7 This brief review will discuss a practical approach to the use of TDM in IBD with a focus on its use with anti-TNF therapies.

Reactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

Reactive TDM more rationally guides therapeutic decisions for dealing with loss of response to anti-TNF therapy in IBD and is actually more cost-effective.8,9 Patients with sub-therapeutic or undetectable drug concentrations without ADA derive more benefit from dose escalation (increasing the dose or decreasing the interval) compared to those switched to another anti-TNF agent. On the other hand, patients with therapeutic or supra-therapeutic drug concentrations have better outcomes when changing to a medication with a different mechanism of action (as their disease is probably no longer TNF-driven).3 A recent study showed that trough concentration of adalimumab >4.5 mcg/mL or infliximab >3.8 mcg/mL at time of loss of response identifies patients who benefit more from alternative therapies rather than dose escalation or switching to another anti-TNF agent.10 In clinical practice, in order to fully optimize the original anti-TNF, we will typically dose optimize patients to drug concentrations of infliximab and adalimumab to >10 mcg/mL before giving up and changing medications. Moreover, patients with high ADA titer have better outcomes when switched to another anti-TNF rather than undergo further dose escalation.3 Vande Casteele et al, showed that antibodies to infliximab (ATI) >9.1 U/mL at time of loss of response resulted in a likelihood ratio of 3.6 for an unsuccessful intervention, defined as the need to initiate corticosteroids, immunomodulators (IMM), or other medications or infliximab discontinuation within two infusions after the intervention (shorten of infusion intervals, dose increase to 10 mg/kg, or a combination of both).11 A proposed treatment algorithm for using reactive TDM for anti-TNF therapy is shown in Figure 1.

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy

TDM of thiopurines

Anti-TNF TDM assays

Conclusions

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the clinical utility of TDM of anti-TNF therapy in IBD clinical practice and a move towards personalized medicine, as it is now clear that “one dose does not fit all patients.” Nevertheless, before a TDM-based approach can be widely implemented and emerge as the new standard-of-care for anti-TNF therapy in IBD, several barriers regarding cost issues (insurance coverage and out of pocket expenses), time lag from serum sampling to test results (typically 5 to 10 days), proper interpretation and application of the results, type of assay used, and the optimal timing of serum collection should be overcome. Initiatives are already underway including the development of accurate, easily accessible, and affordable rapid assays that will allow anti-TNF concentration measurement at the point-of-care site and software-decision support tools or ‘dashboards’ that will incorporate a predictive PK model based on patient and disease characteristics.29,30 Additionally, more data from well-designed prospective studies and randomized controlled trials regarding both induction and maintenance treatment and for all available biologics (originators and biosimilars) are urgently needed. A panel consisting of members of the Building Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Globally research alliance (www.BRIDGeIBD.com), and recognized leaders in the field of TDM in IBD has recently published recommendations that help clinicians on the appropriate timing and best way to interpret and respond to TDM results depending on the specific clinical scenario.31

Funding: KP received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD.

Potential competing interests: K.P.: nothing to disclose; A.S.C: received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

Dr. Papamichail is a research fellow and Dr. Cheifetz is the director of the Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, division of gastroenterology, Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Papamichail received a fellowship grant from the Hellenic Group for the study of IBD. Dr. Cheifetz received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Janssen, UCB, Takeda, Prometheus, and Pfizer.

References

1. Miligkos M, Papamichael K, Casteele NV, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha versus anti-integrin agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a network meta-analysis of indirect comparisons. Clin Ther. 2016;38(6):1342-1358.e6

2. Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):182-97

3. Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Use of anti-TNF drug levels to optimise patient management. Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7;289-300.

4. Papamichael K, Baert F, Tops S, et al. Post-Induction Adalimumab concentration is associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:53-59

5. Papamichael K, Van Stappen T, Vande Casteele N, et al. Infliximab concentration thresholds during induction therapy are associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:543-9.

6. Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing Anti-TNF-Alpha Therapy: Serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:550-557.e2.

7. Singh N, Dubinsky MC. Therapeutic drug monitoring in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a practical approach. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11:48-55.

8. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut 2014;63:919-27.

9. Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, et al. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:654–66.

10. Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:522-30.

11. Casteele NV, Gils A, Singh S, et al. Antibody response to infliximab and its impact on pharmacokinetics can be transient. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:962-71.

12. Vaughn BP, Martinez-Vazquez M, Patwardhan VR, et al. Proactive therapeutic concentration monitoring of infliximab may improve outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a pilot observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1996-2003.

13. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1320-9.e3.

14. Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1296–307.e5.

15. Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, et al. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014;63:1721–7.

16. Arias MT, Vande Casteele N, Vermeire S, et al. A panel to predict long-term outcome of infliximab therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:531–8.

17. Singh N, Rosenthal CJ, Melmed GY, et al Early infliximab trough levels are associated with persistent remission in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1708-13.

18. Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1324–32.

19. Baert F, Kondragunta V, Lockton S, et al. Antibodies to adalimumab are associated with future inflammation in Crohn’s patients receiving maintenance adalimumab therapy: a post hoc analysis of the Karmiris trial. Gut 2016;65:1126–31.

20. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Allez M, et al. Association between plasma concentrations of certolizumab pegol and endoscopic outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:423-31.e1

21. Pariente B, Laharie D. Review article: why, when and how to de-escalate therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:338–53.

22. Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, et al. Early trough levels and antibodies to infliximab predict safety and success of reinitiation of infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1474-81.e2

23. Osterman MT, Kundu R, Lichtenstein GR, Lewis JD. Association of 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and inflammatory bowel disease activity: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1047-53

24. Dassopoulos T, Dubinsky MC, Bentsen JL, et al. Randomised clinical trial: individualised vs. weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:163-175.

25. Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wang S, et al. Algorithms outperform metabolite tests in predicting response of patients with inflammatory bowel disease to thiopurines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:143-150.

26. Yarur A, Kubiliun M, Czul F, et al. Concentrations of 6-thioguanine nucleotide correlate with trough levels of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on combination therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1118-1124.

27. Marini JC, Sendecki J, Cornillie F, et al. Comparisons of serum infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab tests used in inflammatory bowel disease clinical trials of Remicade®.AAPS J. 2016 Sep 6. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1208/s12248-016-9981-3

28. Gils A, Vande Casteele N, Poppe R, et al. Development of a universal anti-adalimumab antibody standard for interlaboratory harmonization. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36:669-673.

29. Van Stappen T, Bollen L, Vande Casteele N, et al. Rapid test for infliximab drug concentration allows immediate dose adaptation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7:e206

30. Dubinsky MC, Phan BL, Singh N, et al. Pharmacokinetic dashboard-recommended dosing is different than standard of care dosing in infliximab-treated pediatric IBD patients. AAPS J. 2016 Oct 13. [Epub ahead of print]

31. Melmed GY, Irving PM, Jones J, et al. Appropriateness of testing for anti-tumor necrosis factor agent and antibody concentrations, and interpretation of results. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1302-9.

32. Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:601-8.

33. Drobne D, Bossuyt P, Breynaert C, et al. Withdrawal of immunomodulators after co-treatment does not reduce trough level of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:514-21.e4.

An 87-Year-Old Woman With Recurrent Dysphagia

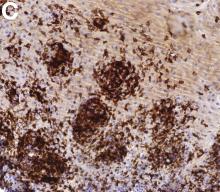

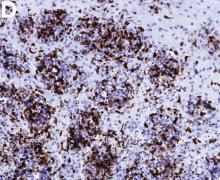

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

Previously Published in Gastroenterology (2016;151:1085-6)

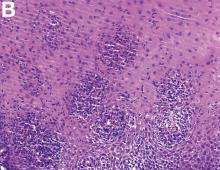

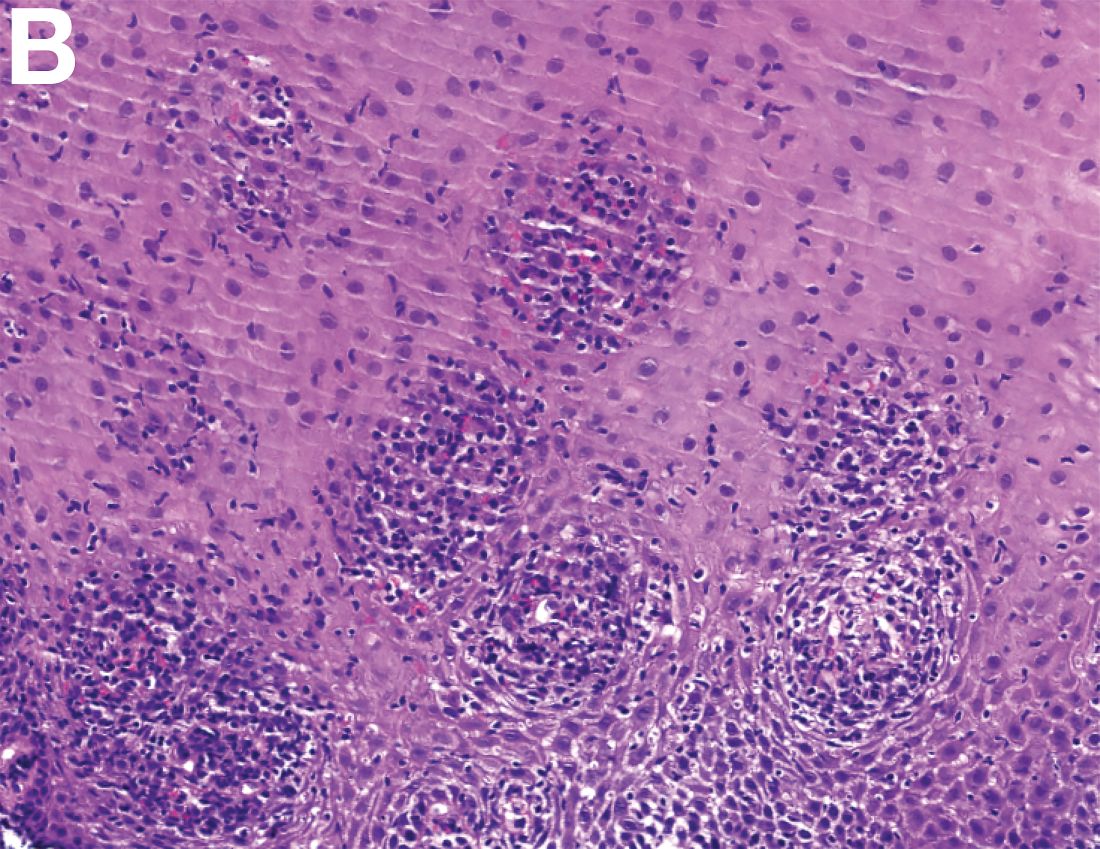

An 87-year-old woman was referred due to dysphagia that had been present for several years. Three years prior to this presentation she had undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) on the same indication showing a proximal and a distal esophageal benign-appearing stricture but no signs of esophagitis. Both were dilated and biopsied. Histopathology showed infiltration with lymphocytes and neutrophilic granulocytes, and superficially fungal hyphae and spores. No predominance of eosinophilic granulocytes was noted. A proton-pump inhibitor was prescribed and she was scheduled for a control gastroscopy, but was lost to follow-up. She was otherwise healthy without any allergies.

Upon re-presentation, she was under treatment with pantoprazole 40 mg OD. Upon EGD a spiral-shaped proximal esophageal stricture with normal-appearing mucosa only passable with a nasal endoscope was observed. The rest of the esophagus was seen with mucosal concentric rings (Figure A; video). The esophageal mucosa was otherwise endoscopically normal throughout. Biopsies were taken from the distal and proximal esophagus. Balloon dilation of the proximal stricture was performed (CRE, Boston Scientific) to 13.5 mm (video). Subsequently, a standard gastroscope could be passed to the duodenum revealing normal-appearing gastric and duodenal mucosa.

Dr. Havre and Dr. Kalaitzakis are in the Endoscopy Unit of Copenhagen University Hospital/Herlev, University of Copenhagen. Ms. Hallager is in the department of pathology, Copenhagen University Hospital/Herlev. The authors disclose no conflicts.