User login

Adult ADHD: 6 studies of nonpharmacologic interventions

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional impairment.1 ADHD begins in childhood, continues into adulthood, and has negative consequences in many facets of adult patients’ lives, including their careers, daily functioning, and interpersonal relationships.2 According to the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence’s recommendations, both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are advised for patients with ADHD.3 Although various pharmacotherapies are advised as first-line treatments for ADHD, they are frequently linked to unfavorable adverse effects, partial responses, chronic residual symptoms, high dropout rates, and issues with addiction.4 As a result, there is a need for evidence-based nonpharmacologic therapies.

In a systematic review, Nimmo-Smith et al5 found that certain nonpharmacologic treatments can be effective in helping patients with ADHD manage their illness. In clinical and cognitive assessments of ADHD, a recent meta-analysis found that noninvasive brain stimulation had a small but significant effect.6 Some evidence suggests that in addition to noninvasive brain stimulation, other nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation (PE), mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and chronotherapy, can be effective as an adjunct treatment to pharmacotherapy, and possibly as monotherapy.

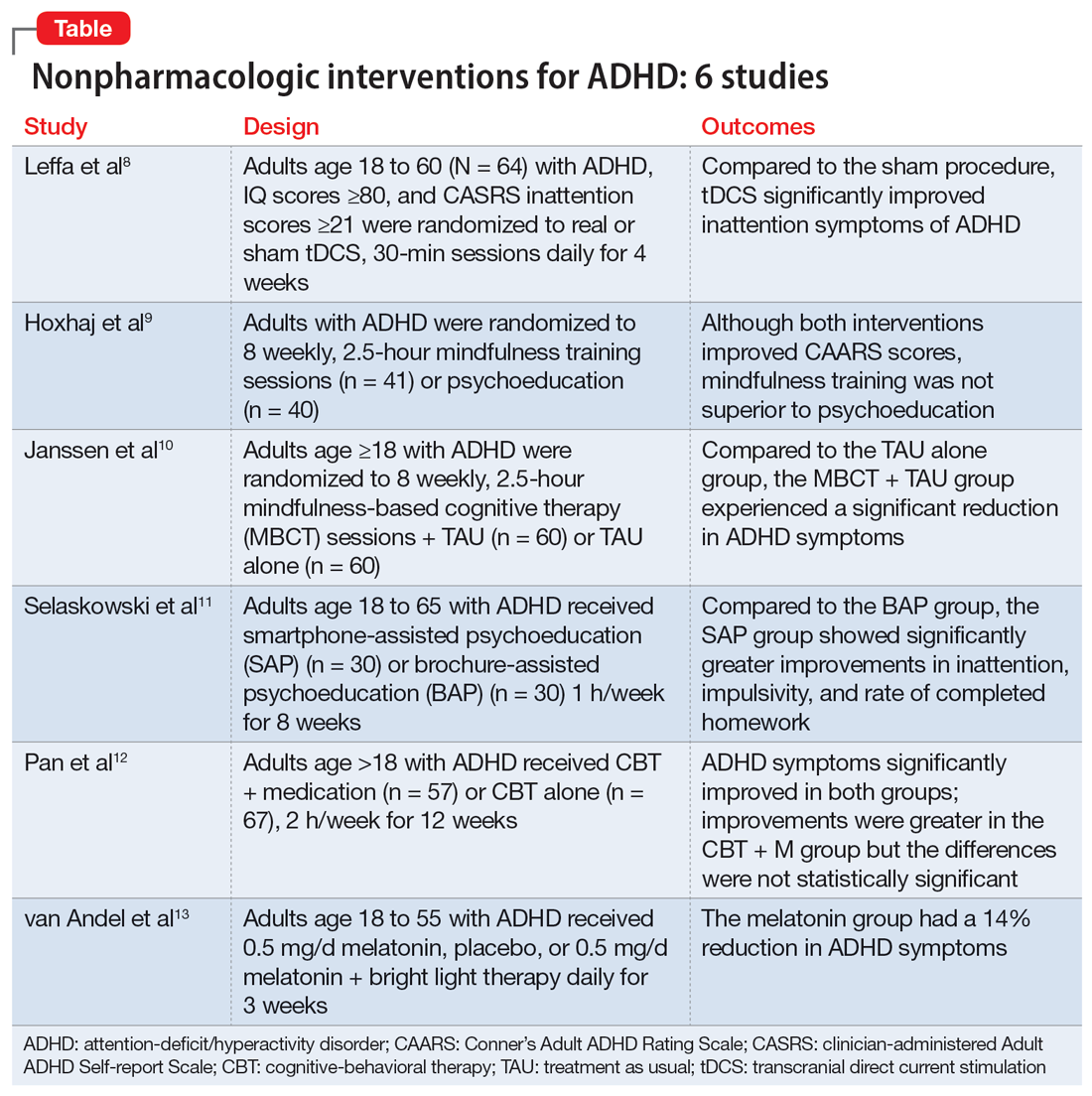

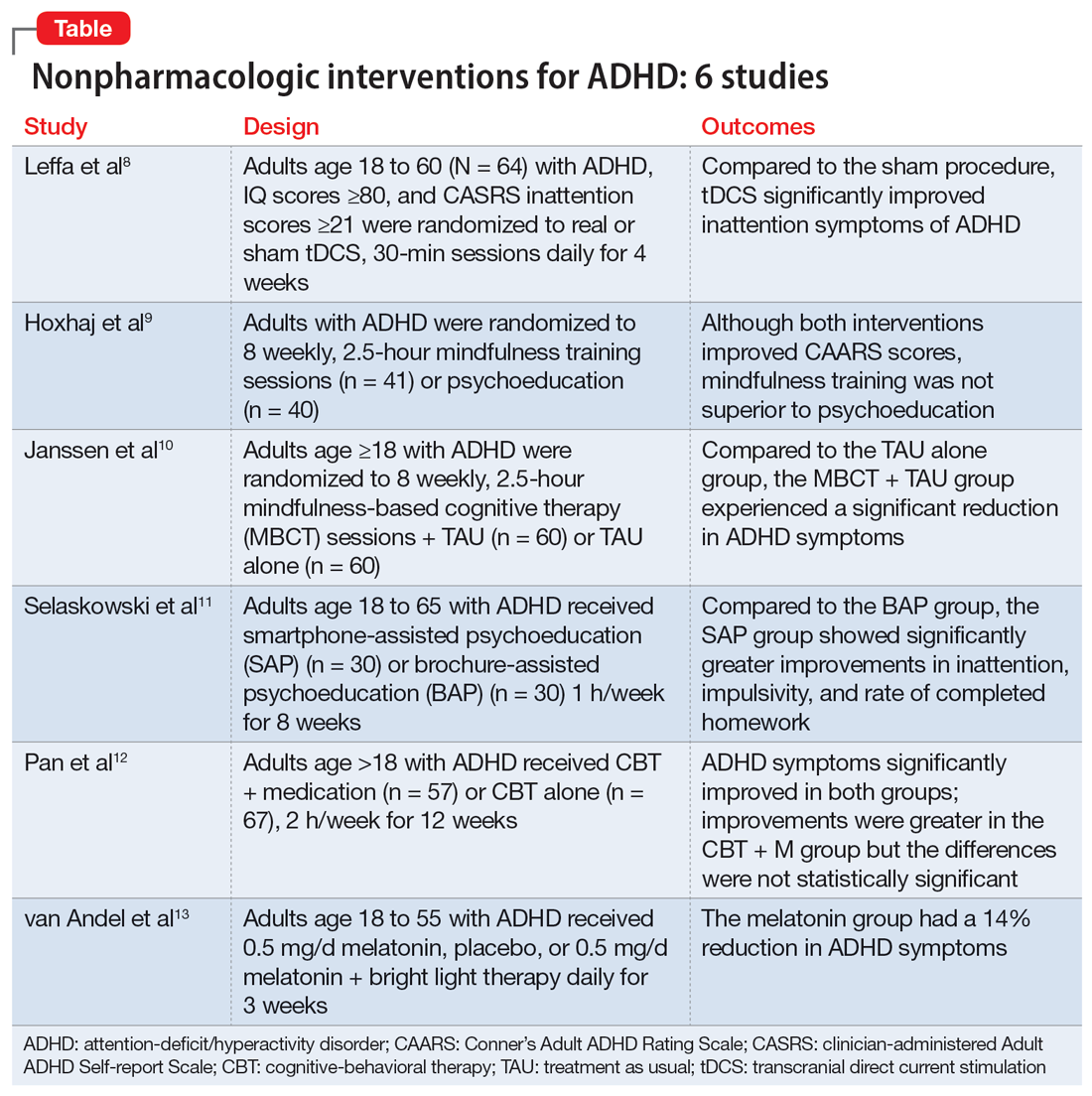

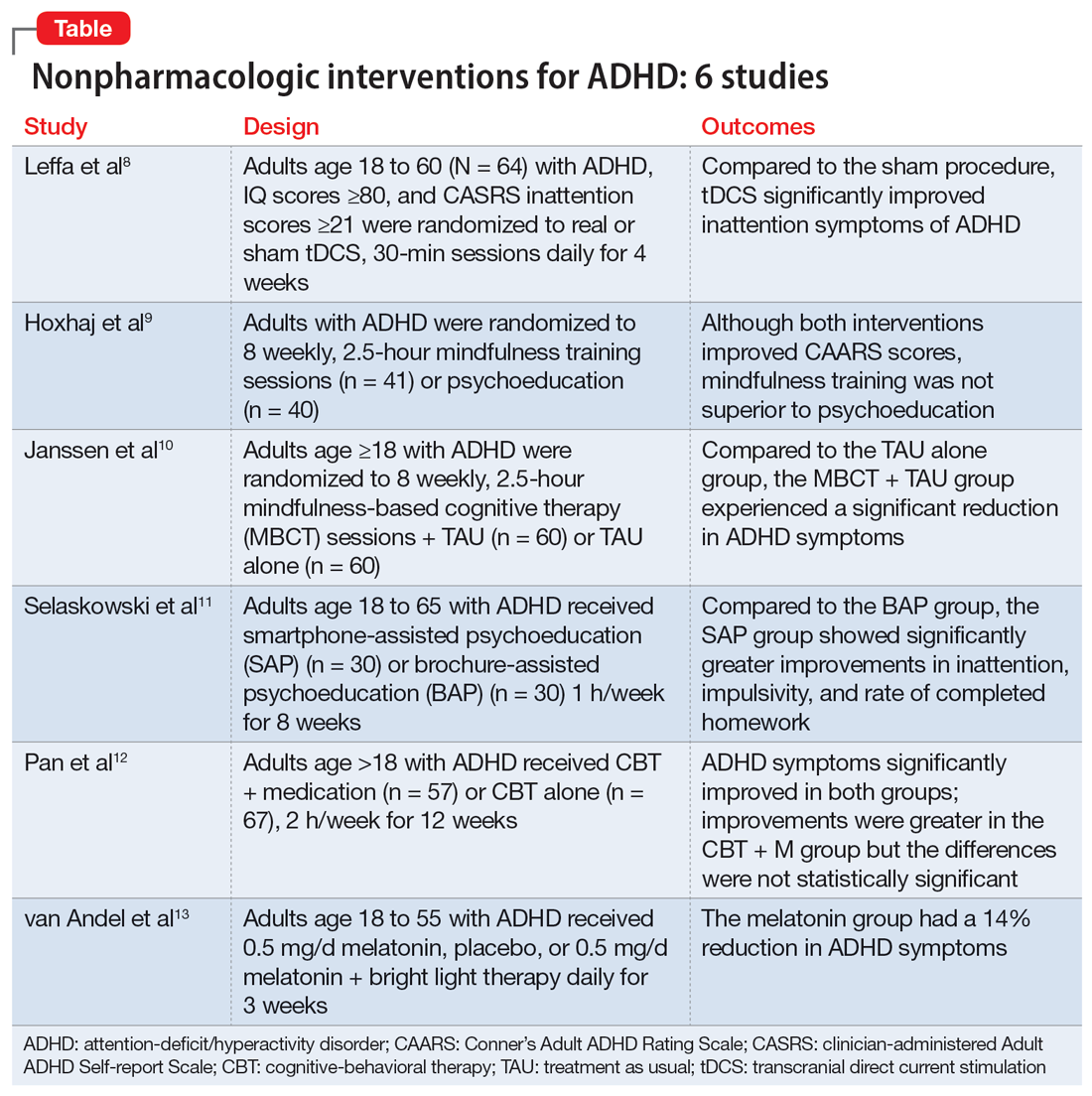

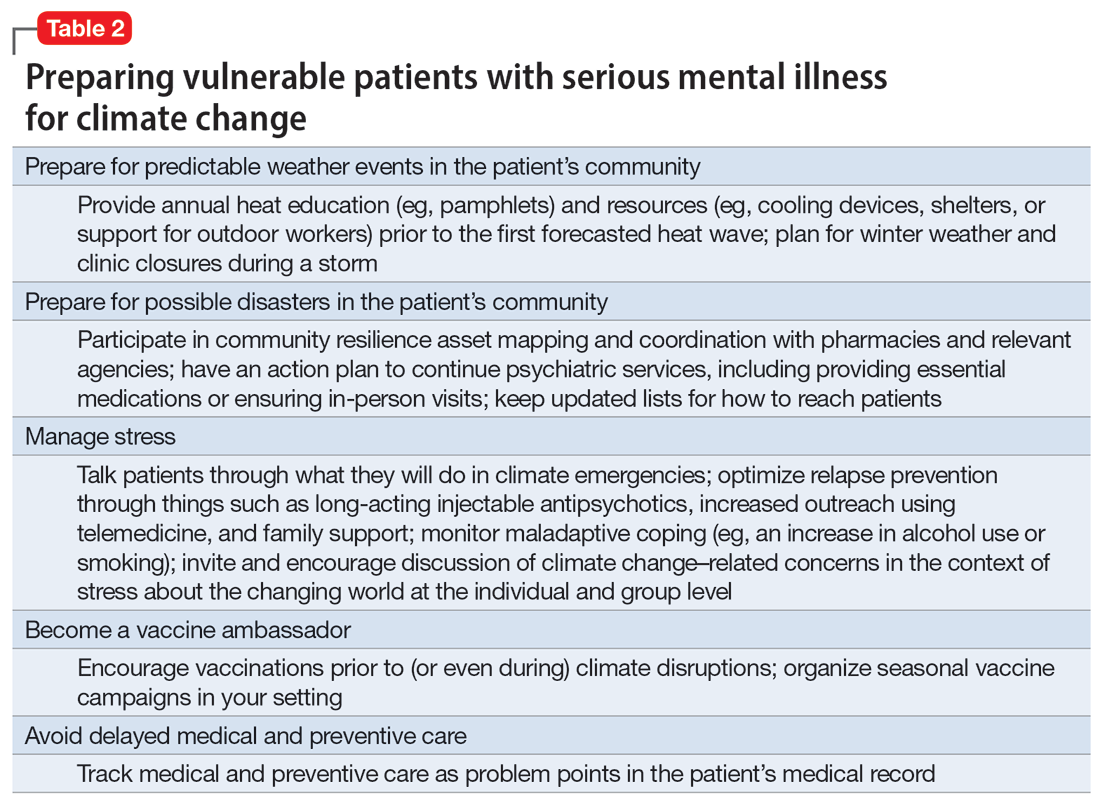

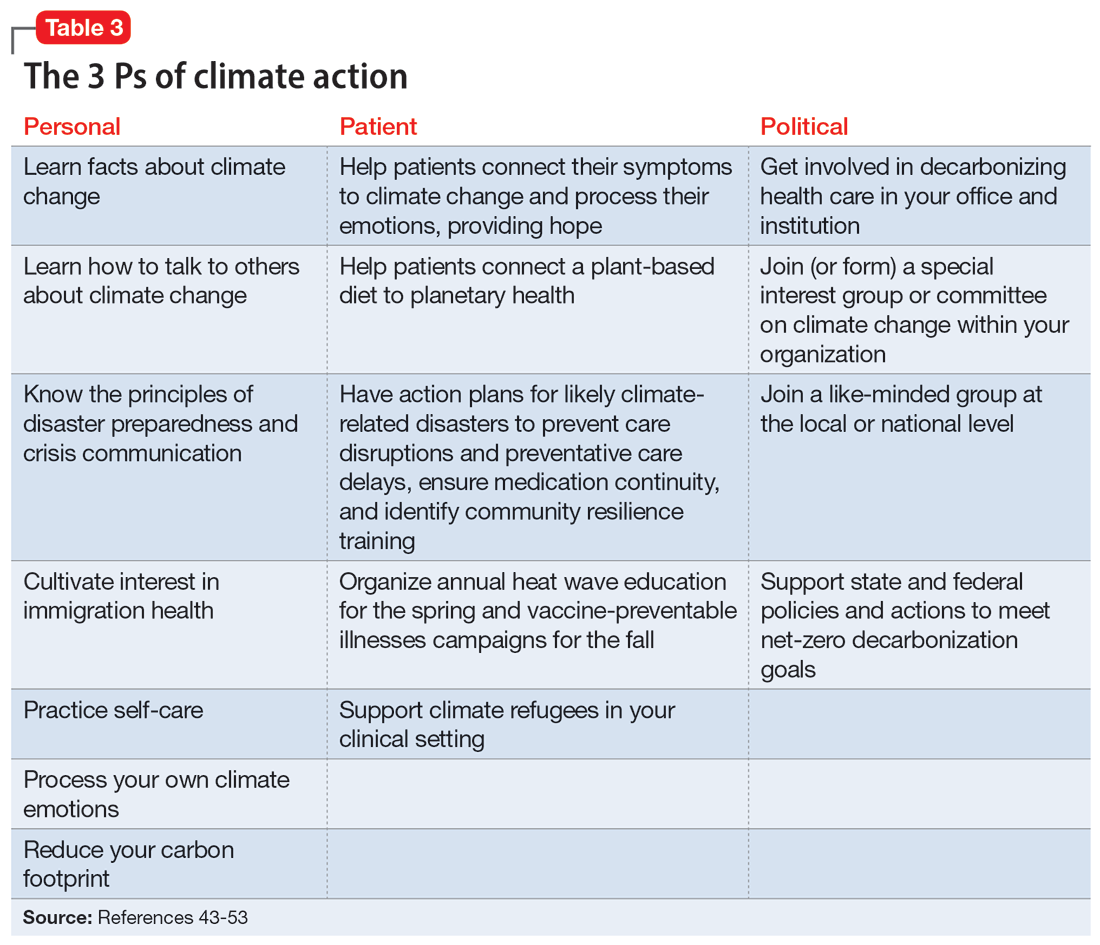

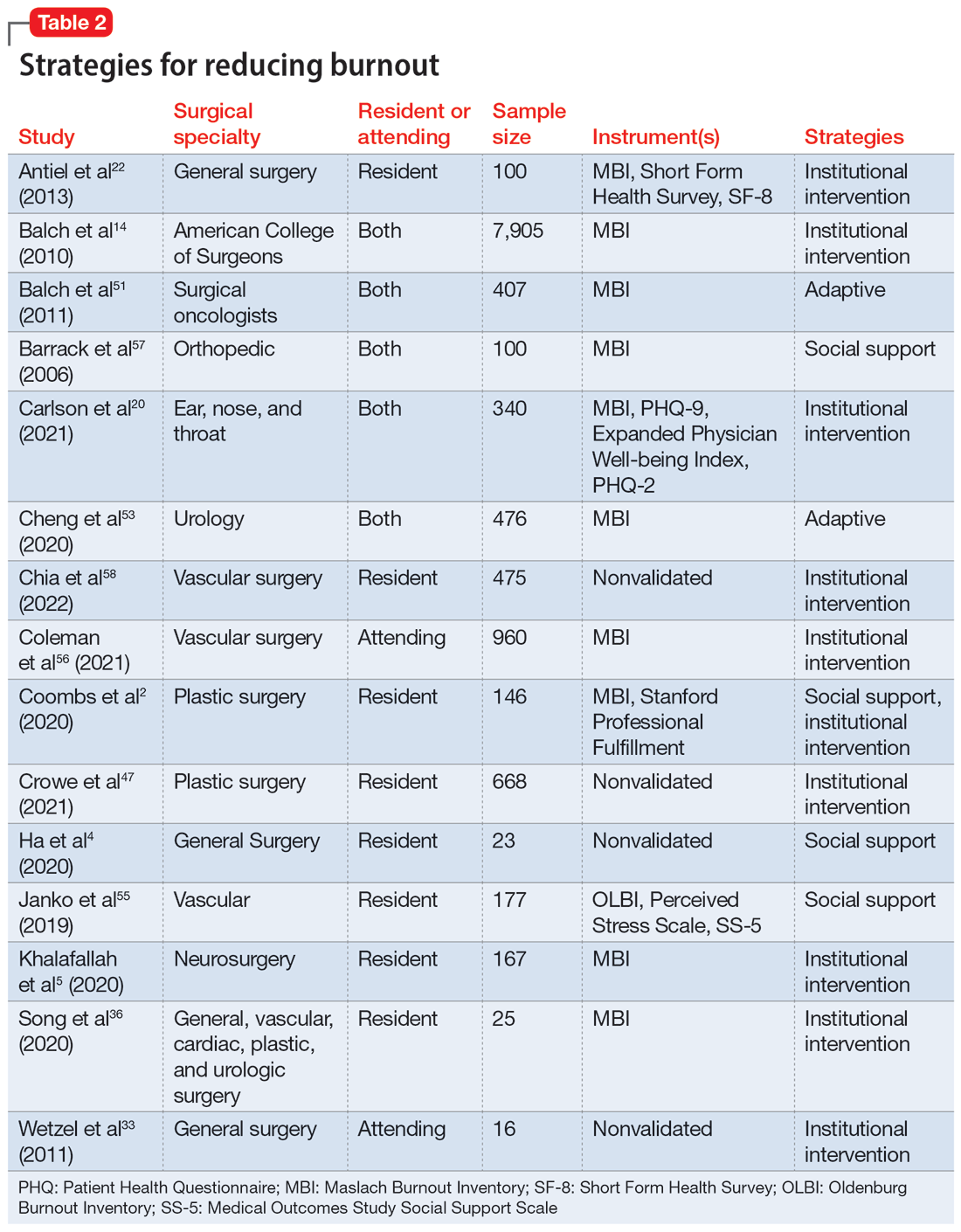

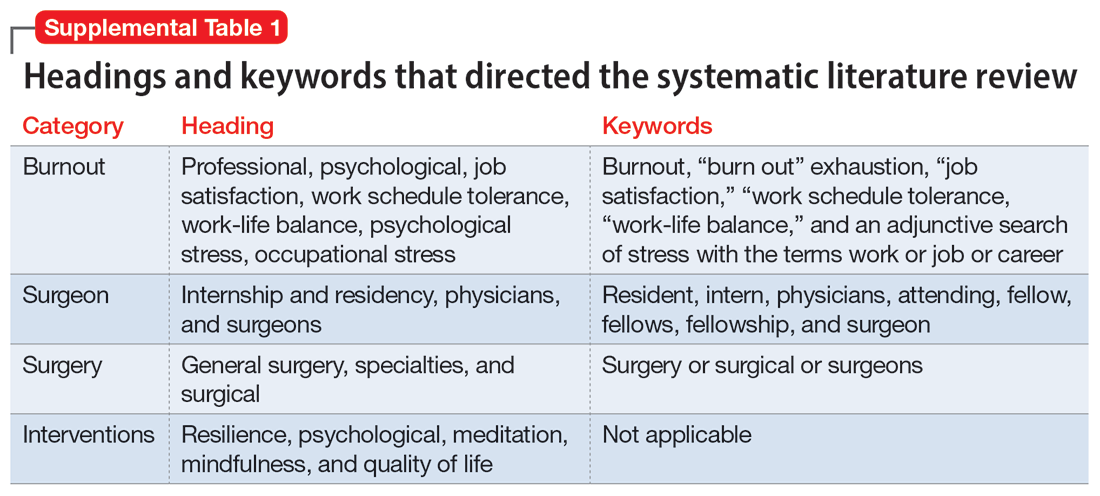

Part 1 of this 2-part article reviewed 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years.7 Part 2 analyzes 6 RCTs of nonpharmacologic treatments for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table8-13).

1. Leffa DT, Grevet EH, Bau CHD, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the TUNED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(9):847-856. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2055

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) uses noninvasive, low-intensity electrical current on the scalp to affect underlying cortical activity.14 This form of neurostimulation offers an alternative treatment option for when medications fail or are not tolerated, and can be used at home without the direct involvement of a clinician.14 tDCS as a treatment for ADHD has been increasingly researched, though many studies have been limited by short treatment periods and varied methodological approaches. In a meta-analysis, Westwood et al6 found a trend toward improvement on the function of processing speed but not on attention. Leffa et al8 examined the efficacy and safety of a 4-week course of home-based tDCS in adult patients with ADHD, specifically looking at reduction in inattention symptoms.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel, sham-controlled clinical trial evaluated 64 participants age 18 to 60 from a single center in Brazil who met DSM-5 criteria for combined or primarily inattentive ADHD.

- Inclusion criteria included an inattention score ≥21 on the clinician-administered Adult ADHD Self-report Scale version 1.1 (CASRS). This scale assesses both inattentive symptoms (CASRS-I) and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (CASRS-HI). Participants were not being treated with stimulants or agreed to undergo a 30-day washout of stimulants prior to the study.

- Exclusion criteria included current moderate to severe depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II [BDI] score >21), current moderate to severe anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI] score ≥21), diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BD) with either a manic or depressive episode in the year prior to study, diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), positive screen for substance use, unstable medical condition resulting in poor functionality, pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant within 3 months of the study, not able to use home-based equipment, history of neurosurgery, presence of ferromagnetic metal in the head or presence of implanted medical devices in head/neck region, or history of epilepsy with reported seizures in the year prior to the study.

- Participants were randomized to self-administer real or sham tDCS; the devices looked the same. Participants underwent daily 30-minute sessions using a 2-mA direct constant current for a total of 28 sessions. Sham treatment involved a 30-second ramp-up to 2-mA and a 30-second ramp-down sensation at the beginning, middle, and end of each respective session.

- The primary outcome was a change in symptoms of inattention per CASRS-I. Secondary outcomes were scores on the CASRS-HI, BDI, BAI, and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions-Adult (BRIEF-A), which evaluates executive function.

Outcomes

- A total of 53 participants used stimulant medications prior to the study and 8 required a washout. The average age was 38.3, and 53% of participants were male.

- For the 55 participants who completed 4 weeks of treatment, the mean number of sessions was 25.2 in the tDCS group and 24.8 in the sham group.

- At the end of Week 4, there was a statistically significant treatment by time interaction in CASRS-I scores in the tDCS group compared to the sham group (18.88 vs 23.63 on final CASRS-I scores; P < .001).

- There were no statistically significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study showed the benefits of 4 weeks of home-based tDCS for managing inattentive symptoms in adults with ADHD. The authors noted that extended treatment of tDCS may incur greater benefit, as this study used a longer treatment course compared to others that have used a shorter duration of treatment (ie, days instead of weeks). Additionally, this study placed the anodal electrode over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) vs over the left DLPFC, because there may be a decrease in activation in the right DLPFC in adults with ADHD undergoing attention tasks.15

- This study also showed that home-based tDCS can be an easier and more accessible way for patients to receive treatment, as opposed to needing to visit a health care facility.

- Limitations: The dropout rate (although only 2 of 7 participants who dropped out of the active group withdrew due to adverse events), lack of remote monitoring of patients, and restrictive inclusion criteria limit the generalizability of these findings. Additionally, 3 patients in the tDCS group and 7 in the sham group were taking psychotropic medications for anxiety or depression.

Continue to: #2

2. Hoxhaj E, Sadohara C, Borel P, et al. Mindfulness vs psychoeducation in adult ADHD: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(4):321-335. doi:10.1007/s00406-018-0868-4

Previous research has shown that using mindfulness-based approaches can improve ADHD symptoms.16,17 Hoxhaj et al9 looked at the effectiveness of mindfulness awareness practices (MAP) for alleviating ADHD symptoms.

Study design

- This RCT enrolled 81 adults from a German medical center who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, were not taking any ADHD medications, and had not undergone any psychotherapeutic treatments in the last 3 months. Participants were randomized to receive MAP (n = 41) or PE (n = 40).

- Exclusion criteria included having a previous diagnosis of schizophrenia, BD I, active substance dependence, ASD, suicidality, self-injurious behavior, or neurologic disorders.

- The MAP group underwent 8 weekly 2.5-hour sessions, plus homework involving meditation and other exercises. The PE group was given information regarding ADHD and management options, including organization and stress management skills.

- Patients were assessed 2 weeks before treatment (T1), at the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- The primary outcome was the change in the blind-observer rated Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) inattention/memory scales from T1 to T2.

- Secondary outcomes included the other CAARS subscales, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the BDI, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ).

Outcomes

- Baseline demographics did not differ between groups other than the MAP group having a significantly higher IQ than the PE group. However, this difference resolved after the final sample was analyzed, as there were 2 dropouts and 7 participants lost to follow-up in the MAP group and 4 dropouts and 4 participants lost to follow-up in the PE group.

- There was no significant difference between the groups in the primary outcome of observer-rated CAARS inattention/memory subscale scores, or other ADHD symptoms per the CAARS.

- However, there was a significant difference within each group on all ADHD subscales of the observer-rated CAARS at T2. Persistent, significant differences were noted for the observer-rated CAARS subscales of self-concept and DSM-IV Inattentive Symptoms, and all CAARS self-report scales to T3.

- Compared to the PE group, there was a significantly larger improvement in the MAP group on scores of the mindfulness parameters of observation and nonreactivity to inner experience.

- There were significant improvements regarding depression per the BDI and global severity per the BSI in both treatment groups, with no differences between the groups.

- At T3, in the MAP group, 3 patients received methylphenidate, 1 received atomoxetine, and 1 received antidepressant medication. In the PE group, 2 patients took methylphenidate, and 2 participants took antidepressants.

- There was a significant difference regarding sex and response, with men experiencing less overall improvement than women.

Conclusions/limitations

- MAP was not superior to PE in terms of changes on CAARS scores, although within each group, both therapies showed improvement over time.

- While there may be gender-specific differences in processing information and coping strategies, future research should examine the differences between men and women with different therapeutic approaches.

- Limitations: This study did not employ a true placebo but instead had 2 active arms. Generalizability is limited due to a lack of certain comorbidities and use of medications.

Continue to: #3

3. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000429

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a form of psychotherapy that combines mindfulness with the principles of CBT. Hepark et al18 found benefits of MBCT for reducing ADHD symptoms. In a larger, multicenter, single-blind RCT, Janssen et al10 reviewed the efficacy of MBCT compared to treatment as usual (TAU).

Study design

- A total of 120 participants age ≥18 who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were recruited from Dutch clinics and advertisements and randomized to receive MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU alone (n = 60). There were no significant demographic differences between groups at baseline.

- Exclusion criteria included active depression with psychosis or suicidality, active manic episode, tic disorder with vocal tics, ASD, learning or other cognitive impairments, borderline or antisocial personality disorder, substance dependence, or previous participation in MBCT or other mindfulness-based interventions. Participants also had to be able to complete the questionnaires in Dutch.

- Blinded evaluations were conducted at baseline (T0), at the completion of therapy (T1), 3 months after the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- MBCT included 8 weekly, 2.5-hour sessions and a 6-hour silent session between the sixth and seventh sessions. Patients participated in various meditation techniques with the addition of PE, CBT, and group discussions. They were also instructed to practice guided exercises 6 days/week, for approximately 30 minutes/day.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD symptoms as assessed by the investigator-rated CAARS (CAARS-INV) at T1.

- Secondary outcomes included change in scores on the CAARS: Screening Version (CAARS-S:SV), BRIEF-A, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF), Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF), Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF), and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ 45.2).

Outcomes

- In the MBCT group, participants who dropped out (n = 9) were less likely to be using ADHD medication at baseline than those who completed the study.

- At T1, the MBCT plus TAU group had significantly less ADHD symptoms on CAARS-INV compared to TAU (d = 0.41, P = .004), with more participants in the MBCT plus TAU group experiencing a symptom reduction ≥30% (24% vs 7%, P = .001) and remission (P = .039).

- The MBCT plus TAU group also had a significant reduction in scores on CAARS-S:SV as well as significant improvement on self-compassion per SCS-SF, mindfulness skills per FFMQ-SF, and positive mental health per MHC-SF, but not on executive functioning per BRIEF-A or general functioning per OQ 45.2.

- Over 6-month follow-up, there continued to be significant improvement in CAARS-INV, CAARS-S:SV, mindfulness skills, self-compassion, and positive mental health in the MBCT plus TAU group compared to TAU. The difference in executive functioning (BRIEF-A) also became significant over time.

Conclusions/limitations

- MBCT plus TAU appears to be effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, both from a clinician-rated and self-reported perspective, with improvements lasting up to 6 months.

- There were also improvements in mindfulness, self-compassion, and positive mental health posttreatment in the MBCT plus TAU group, with improvement in executive functioning seen over the follow-up periods.

- Limitations: The sample was drawn solely from a Dutch population and did not assess the success of blinding.

Continue to: #4

4. Selaskowski B, Steffens M, Schulze M, et al. Smartphone-assisted psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114802. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114802

Managing adult ADHD can include PE, but few studies have reviewed the effectiveness of formal clinical PE. PE is “systemic, didactic-psychotherapeutic interventions, which are adequate for informing patients and their relatives about the illness and its treatment, facilitating both an understanding and personally responsible handling of the illness and supporting those afflicted in coping with the disorder.”19 Selaskowski et al11 investigated the feasibility of using smartphone-assisted PE (SAP) for adults diagnosed with ADHD.

Study design

- Participants were 60 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD. They were required to have a working comprehension of the German language and access to an Android-powered smartphone.

- Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, severe affective disorder, severe neurologic disorder, or initial use or dose change of ADHD medications 2 weeks prior to baseline.

- Participants were randomized to SAP (n = 30) or brochure-assisted PE (BAP) (n = 30). The demographics at baseline were mostly balanced between the groups except for substance abuse (5 in the SAP group vs 0 in the BAP group; P = .022).

- The primary outcome was severity of total ADHD symptoms, which was assessed by blinded evaluations conducted at baseline (T0) and after 8 weekly PE sessions (T1).

- Secondary outcomes included dropout rates, improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by the German BDI-II, improvement in functional impairment as measured by the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale (WFIRS), homework performed, attendance, and obtained PE knowledge.

- Both groups attended 8 weekly 1-hour PE group sessions led by 2 therapists and comprised of 10 participants.

Outcomes

- Only 43 of the 60 initial participants completed the study; 24 in the SAP group and 19 in the BAP group.

- The SAP group experienced a significant symptom improvement of 33.4% from T0 to T1 compared to the BAP group, which experienced a symptom improvement of 17.3% (P = .019).

- ADHD core symptoms considerably decreased in both groups. There was no significant difference between groups (P = .74).

- SAP dramatically improved inattention (P = .019), improved impulsivity (P = .03), and increased completed homework (P < .001), compared to the BAP group.

- There was no significant difference in correctly answered quiz questions or in BDI-II or WFIRS scores.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both SAP and BAP appear to be effective methods for PE, but patients who participated in SAP showed greater improvements than those who participated in BAP.

- Limitations: This study lacked a control intervention that was substantially different from SAP and lacked follow-up. The sample was a mostly German population, participants were required to have smartphone access beforehand, and substance abuse was more common in the SAP group.

Continue to: #5

5. Pan MR, Huang F, Zhao MJ, et al. A comparison of efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and CBT combined with medication in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:23-33. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.040

CBT has demonstrated long-term benefit for the core symptoms of ADHD, comorbid symptoms (anxiety and depression), and social functioning. For ADHD, pharmacotherapies have a bottom-up effect where they increase neurotransmitter concentration, leading to an effect in the prefrontal lobe, whereas psychotherapies affect behavior-related brain activity in the prefrontal lobes, leading to the release of neurotransmitters. Pan et al12 compared the benefits of CBT plus medication (CBT + M) to CBT alone on core ADHD symptoms, social functioning, and comorbid symptoms.

Study design

- The sample consisted of 124 participants age >18 who had received a diagnosis of adult ADHD according to DSM-IV via Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview and were either outpatients at Peking University Sixth Hospital or participants in a previous RCT (Huang et al20).

- Exclusion criteria included organic mental disorders, high suicide risk in those with major depressive disorder, acute BD episode requiring medication or severe panic disorder or psychotic disorder requiring medication, pervasive developmental disorder, previous or current involvement in other psychological therapies, IQ <90, unstable physical conditions requiring medical treatment, attending <7 CBT sessions, or having serious adverse effects from medication.

- Participants received CBT + M (n = 57) or CBT alone (n = 67); 40 (70.18%) participants in the CBT + M group received methylphenidate hydrochloride controlled-release tablets (average dose 27.45 ± 9.97 mg) and 17 (29.82%) received atomoxetine hydrochloride (average dose 46.35 ± 20.09 mg). There were no significant demographic differences between groups.

- CBT consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour sessions (8 to 12 participants in each group) that were led by 2 trained psychiatrist therapists and focused on behavioral and cognitive strategies.

- Participants in the CBT alone group were drug-naïve and those in CBT + M group were stable on medications.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) score from baseline to Week 12.

- Secondary outcomes included Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-Esteem Scale (SES), executive functioning (BRIEF-A), and quality of life (World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief version [WHOQOL-BREF]).

Outcomes

- ADHD-RS total, impulsiveness-hyperactivity subscale, and inattention subscale scores significantly improved in both groups (P < .01). The improvements were greater in the CBT + M group compared to the CBT-only group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

- There was no significant difference between groups in remission rate (P < .689).

- There was a significant improvement in SAS, SES, and SDS scores in both groups (P < .01).

- In terms of the WHOQOL-BREF, the CBT + M group experienced improvements only in the psychological and environmental domains, while the CBT-only group significantly improved across the board. The CBT-only group experienced greater improvement in the physical domain (P < .01).

- Both groups displayed considerable improvements in the Metacognition Index and Global Executive Composite for BRIEF-A. The shift, self-monitor, initiate, working memory, plan/organize, task monitor, and material organization skills significantly improved in the CBT + M group. The only areas where the CBT group significantly improved were initiate, material organization, and working memory. No significant differences in BRIEF-A effectiveness were discovered.

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT is an effective treatment for improving core ADHD symptoms.

- This study was unable to establish that CBT alone was preferable to CBT + M, particularly in terms of core symptoms, emotional symptoms, or self-esteem.

- CBT + M could lead to a greater improvement in executive function than CBT alone.

- Limitations: This study used previous databases rather than RCTs. There was no placebo in the CBT-only group. The findings may not be generalizable because participants had high education levels and IQ. The study lacked follow-up after 12 weeks.

Continue to: #6

6. van Andel E, Bijlenga D, Vogel SWN, et al. Effects of chronotherapy on circadian rhythm and ADHD symptoms in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delayed sleep phase syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(2):260-269. doi:10.1080/07420528.2020.1835943

Most individuals with ADHD have a delayed circadian rhythm.21 Delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) is diagnosed when a persistently delayed circadian rhythm is not brought on by other diseases or medications. ADHD symptoms and circadian rhythm may both benefit from DSPS treatment. A 3-armed randomized clinical parallel-group trial by van Andel et al13 investigated the effects of chronotherapy on ADHD symptoms and circadian rhythm.

Study design

- Participants were Dutch-speaking individuals age 18 to 55 who were diagnosed with ADHD and DSPS. They were randomized to receive melatonin 0.5 mg/d (n = 17), placebo (n = 17), or melatonin 0.5 mg/d plus 30 minutes of timed morning bright light therapy (BLT) (n = 15) daily for 3 weeks. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups except that the melatonin plus BLT group had higher use of oral contraceptives (P = .007).

- This study was completed in the Netherlands with participants from an outpatient adult ADHD clinic.

- Exclusion criteria included epilepsy, psychotic disorders, anxiety or depression requiring acute treatment, alcohol intake >15 units/week in women or >21 units/week in men, ADHD medications, medications affecting sleep, use of drugs, mental retardation, amnestic disorder, dementia, cognitive dysfunction, crossed >2 time zones in the 2 weeks prior to the study, shift work within the previous month, having children disturbing sleep, glaucoma, retinopathy, having BLT within the previous month, pregnancy, lactation, or trying to conceive.

- The study consisted of 3-armed placebo-controlled parallel groups in which 2 were double-blind (melatonin group and placebo group).

- During the first week of treatment, medication was taken 3 hours before dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) and later advanced to 4 and 5 hours in Week 2 and Week 3, respectively. BLT was used at 20 cm from the eyes for 30 minutes every morning between 7

am and 8am . - The primary outcome was DLMO in which radioimmunoassay was used to determine melatonin concentrations. DLMO was used as a marker for internal circadian rhythm.

- The secondary outcome was ADHD symptoms using the Dutch version of the ADHD Rating Scale-IV.

- Evaluations were conducted at baseline (T0), the conclusion of treatment (T1), and 2 weeks after the end of treatment (T2).

Outcomes

- Out of 51 participants, 2 dropped out of the melatonin plus BLT group before baseline, and 3 dropped out of the placebo group before T1.

- At baseline, the average DLMO was 11:43

pm ± 1 hour and 46 minutes, with 77% of participants experiencing DLMO after 11pm . Melatonin advanced DLMO by 1 hour and 28 minutes (P = .001) and melatonin plus BLT had an advance of 1 hour and 58 minutes (P < .001). DLMO was unaffected by placebo. - The melatonin group experienced a 14% reduction in ADHD symptoms (P = .038); the placebo and melatonin plus BLT groups did not experience a reduction.

- DLMO and ADHD symptoms returned to baseline 2 weeks after therapy ended.

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with DSPS and ADHD, low-dose melatonin can improve internal circadian rhythm and decrease ADHD symptoms.

- Melatonin plus BLT was not effective in improving ADHD symptoms or advancing DLMO.

- Limitations: This study used self-reported measures for ADHD symptoms. The generalizability of the findings is limited because the exclusion criteria led to minimal comorbidity. The sample was comprised of a mostly Dutch population.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

2. Goodman DW. The consequences of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13(5):318-327. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000290670.87236.18

3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. 2019. Accessed February 9, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493361/

4. Cunill R, Castells X, Tobias A, et al. Efficacy, safety and variability in pharmacotherapy for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression in over 9000 patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(2):187-197. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-4099-3

5. Nimmo-Smith V, Merwood A, Hank D, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for adult ADHD: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2020;50(4):529-541. doi:10.1017/S0033291720000069

6. Westwood SJ, Radua J, Rubia K. Noninvasive brain stimulation in children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021;46(1):E14-E33. doi:10.1503/jpn.190179

7. Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):17-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

8. Leffa DT, Grevet EH, Bau CHD, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the TUNED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(9):847-856. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2055

9. Hoxhaj E, Sadohara C, Borel P, et al. Mindfulness vs psychoeducation in adult ADHD: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(4):321-335. doi:10.1007/s00406-018-0868-4

10. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000429

11. Selaskowski B, Steffens M, Schulze M, et al. Smartphone-assisted psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114802. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114802

12. Pan MR, Huang F, Zhao MJ, et al. A comparison of efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and CBT combined with medication in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:23-33. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.040

13. van Andel E, Bijlenga D, Vogel SWN, et al. Effects of chronotherapy on circadian rhythm and ADHD symptoms in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delayed sleep phase syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(2):260-269. doi:10.1080/07420528.2020.1835943

14. Philip NS, Nelson B, Frohlich F, et al. Low-intensity transcranial current stimulation in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(7):628-639. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16090996

15. Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, et al. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):185-198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277

16. Zylowska L, Ackerman DL, Yang MH, et al. Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: a feasibility study. J Atten Disord. 2008;11(6):737-746. doi:10.1177/1087054707308502

17. Mitchell JT, McIntyre EM, English JS, et al. A pilot trial of mindfulness meditation training for ADHD in adulthood: impact on core symptoms, executive functioning, and emotion dysregulation. J Atten Disord. 2017;21(13):1105-1120. doi:10.1177/1087054713513328

18. Hepark S, Janssen L, de Vries A, et al. The efficacy of adapted MBCT on core symptoms and executive functioning in adults with ADHD: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(4):351-362. Doi:10.1177/1087054715613587

19. Bäuml J, Froböse T, Kraemer S, et al. Psychoeducation: a basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1):S1-S9. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl017

20. Huang F, Tang Y, Zhao M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: a randomized clinical trial in China. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(9):1035-1046. doi:10.1177/1087054717725874

21. Van Veen MM, Kooij JJS, Boonstra AM, et al. Delayed circadian rhythm in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and chronic sleep-onset insomnia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1091-1096. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.032

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional impairment.1 ADHD begins in childhood, continues into adulthood, and has negative consequences in many facets of adult patients’ lives, including their careers, daily functioning, and interpersonal relationships.2 According to the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence’s recommendations, both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are advised for patients with ADHD.3 Although various pharmacotherapies are advised as first-line treatments for ADHD, they are frequently linked to unfavorable adverse effects, partial responses, chronic residual symptoms, high dropout rates, and issues with addiction.4 As a result, there is a need for evidence-based nonpharmacologic therapies.

In a systematic review, Nimmo-Smith et al5 found that certain nonpharmacologic treatments can be effective in helping patients with ADHD manage their illness. In clinical and cognitive assessments of ADHD, a recent meta-analysis found that noninvasive brain stimulation had a small but significant effect.6 Some evidence suggests that in addition to noninvasive brain stimulation, other nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation (PE), mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and chronotherapy, can be effective as an adjunct treatment to pharmacotherapy, and possibly as monotherapy.

Part 1 of this 2-part article reviewed 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years.7 Part 2 analyzes 6 RCTs of nonpharmacologic treatments for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table8-13).

1. Leffa DT, Grevet EH, Bau CHD, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the TUNED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(9):847-856. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2055

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) uses noninvasive, low-intensity electrical current on the scalp to affect underlying cortical activity.14 This form of neurostimulation offers an alternative treatment option for when medications fail or are not tolerated, and can be used at home without the direct involvement of a clinician.14 tDCS as a treatment for ADHD has been increasingly researched, though many studies have been limited by short treatment periods and varied methodological approaches. In a meta-analysis, Westwood et al6 found a trend toward improvement on the function of processing speed but not on attention. Leffa et al8 examined the efficacy and safety of a 4-week course of home-based tDCS in adult patients with ADHD, specifically looking at reduction in inattention symptoms.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel, sham-controlled clinical trial evaluated 64 participants age 18 to 60 from a single center in Brazil who met DSM-5 criteria for combined or primarily inattentive ADHD.

- Inclusion criteria included an inattention score ≥21 on the clinician-administered Adult ADHD Self-report Scale version 1.1 (CASRS). This scale assesses both inattentive symptoms (CASRS-I) and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (CASRS-HI). Participants were not being treated with stimulants or agreed to undergo a 30-day washout of stimulants prior to the study.

- Exclusion criteria included current moderate to severe depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II [BDI] score >21), current moderate to severe anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI] score ≥21), diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BD) with either a manic or depressive episode in the year prior to study, diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), positive screen for substance use, unstable medical condition resulting in poor functionality, pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant within 3 months of the study, not able to use home-based equipment, history of neurosurgery, presence of ferromagnetic metal in the head or presence of implanted medical devices in head/neck region, or history of epilepsy with reported seizures in the year prior to the study.

- Participants were randomized to self-administer real or sham tDCS; the devices looked the same. Participants underwent daily 30-minute sessions using a 2-mA direct constant current for a total of 28 sessions. Sham treatment involved a 30-second ramp-up to 2-mA and a 30-second ramp-down sensation at the beginning, middle, and end of each respective session.

- The primary outcome was a change in symptoms of inattention per CASRS-I. Secondary outcomes were scores on the CASRS-HI, BDI, BAI, and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions-Adult (BRIEF-A), which evaluates executive function.

Outcomes

- A total of 53 participants used stimulant medications prior to the study and 8 required a washout. The average age was 38.3, and 53% of participants were male.

- For the 55 participants who completed 4 weeks of treatment, the mean number of sessions was 25.2 in the tDCS group and 24.8 in the sham group.

- At the end of Week 4, there was a statistically significant treatment by time interaction in CASRS-I scores in the tDCS group compared to the sham group (18.88 vs 23.63 on final CASRS-I scores; P < .001).

- There were no statistically significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study showed the benefits of 4 weeks of home-based tDCS for managing inattentive symptoms in adults with ADHD. The authors noted that extended treatment of tDCS may incur greater benefit, as this study used a longer treatment course compared to others that have used a shorter duration of treatment (ie, days instead of weeks). Additionally, this study placed the anodal electrode over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) vs over the left DLPFC, because there may be a decrease in activation in the right DLPFC in adults with ADHD undergoing attention tasks.15

- This study also showed that home-based tDCS can be an easier and more accessible way for patients to receive treatment, as opposed to needing to visit a health care facility.

- Limitations: The dropout rate (although only 2 of 7 participants who dropped out of the active group withdrew due to adverse events), lack of remote monitoring of patients, and restrictive inclusion criteria limit the generalizability of these findings. Additionally, 3 patients in the tDCS group and 7 in the sham group were taking psychotropic medications for anxiety or depression.

Continue to: #2

2. Hoxhaj E, Sadohara C, Borel P, et al. Mindfulness vs psychoeducation in adult ADHD: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(4):321-335. doi:10.1007/s00406-018-0868-4

Previous research has shown that using mindfulness-based approaches can improve ADHD symptoms.16,17 Hoxhaj et al9 looked at the effectiveness of mindfulness awareness practices (MAP) for alleviating ADHD symptoms.

Study design

- This RCT enrolled 81 adults from a German medical center who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, were not taking any ADHD medications, and had not undergone any psychotherapeutic treatments in the last 3 months. Participants were randomized to receive MAP (n = 41) or PE (n = 40).

- Exclusion criteria included having a previous diagnosis of schizophrenia, BD I, active substance dependence, ASD, suicidality, self-injurious behavior, or neurologic disorders.

- The MAP group underwent 8 weekly 2.5-hour sessions, plus homework involving meditation and other exercises. The PE group was given information regarding ADHD and management options, including organization and stress management skills.

- Patients were assessed 2 weeks before treatment (T1), at the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- The primary outcome was the change in the blind-observer rated Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) inattention/memory scales from T1 to T2.

- Secondary outcomes included the other CAARS subscales, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the BDI, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ).

Outcomes

- Baseline demographics did not differ between groups other than the MAP group having a significantly higher IQ than the PE group. However, this difference resolved after the final sample was analyzed, as there were 2 dropouts and 7 participants lost to follow-up in the MAP group and 4 dropouts and 4 participants lost to follow-up in the PE group.

- There was no significant difference between the groups in the primary outcome of observer-rated CAARS inattention/memory subscale scores, or other ADHD symptoms per the CAARS.

- However, there was a significant difference within each group on all ADHD subscales of the observer-rated CAARS at T2. Persistent, significant differences were noted for the observer-rated CAARS subscales of self-concept and DSM-IV Inattentive Symptoms, and all CAARS self-report scales to T3.

- Compared to the PE group, there was a significantly larger improvement in the MAP group on scores of the mindfulness parameters of observation and nonreactivity to inner experience.

- There were significant improvements regarding depression per the BDI and global severity per the BSI in both treatment groups, with no differences between the groups.

- At T3, in the MAP group, 3 patients received methylphenidate, 1 received atomoxetine, and 1 received antidepressant medication. In the PE group, 2 patients took methylphenidate, and 2 participants took antidepressants.

- There was a significant difference regarding sex and response, with men experiencing less overall improvement than women.

Conclusions/limitations

- MAP was not superior to PE in terms of changes on CAARS scores, although within each group, both therapies showed improvement over time.

- While there may be gender-specific differences in processing information and coping strategies, future research should examine the differences between men and women with different therapeutic approaches.

- Limitations: This study did not employ a true placebo but instead had 2 active arms. Generalizability is limited due to a lack of certain comorbidities and use of medications.

Continue to: #3

3. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000429

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a form of psychotherapy that combines mindfulness with the principles of CBT. Hepark et al18 found benefits of MBCT for reducing ADHD symptoms. In a larger, multicenter, single-blind RCT, Janssen et al10 reviewed the efficacy of MBCT compared to treatment as usual (TAU).

Study design

- A total of 120 participants age ≥18 who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were recruited from Dutch clinics and advertisements and randomized to receive MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU alone (n = 60). There were no significant demographic differences between groups at baseline.

- Exclusion criteria included active depression with psychosis or suicidality, active manic episode, tic disorder with vocal tics, ASD, learning or other cognitive impairments, borderline or antisocial personality disorder, substance dependence, or previous participation in MBCT or other mindfulness-based interventions. Participants also had to be able to complete the questionnaires in Dutch.

- Blinded evaluations were conducted at baseline (T0), at the completion of therapy (T1), 3 months after the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- MBCT included 8 weekly, 2.5-hour sessions and a 6-hour silent session between the sixth and seventh sessions. Patients participated in various meditation techniques with the addition of PE, CBT, and group discussions. They were also instructed to practice guided exercises 6 days/week, for approximately 30 minutes/day.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD symptoms as assessed by the investigator-rated CAARS (CAARS-INV) at T1.

- Secondary outcomes included change in scores on the CAARS: Screening Version (CAARS-S:SV), BRIEF-A, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF), Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF), Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF), and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ 45.2).

Outcomes

- In the MBCT group, participants who dropped out (n = 9) were less likely to be using ADHD medication at baseline than those who completed the study.

- At T1, the MBCT plus TAU group had significantly less ADHD symptoms on CAARS-INV compared to TAU (d = 0.41, P = .004), with more participants in the MBCT plus TAU group experiencing a symptom reduction ≥30% (24% vs 7%, P = .001) and remission (P = .039).

- The MBCT plus TAU group also had a significant reduction in scores on CAARS-S:SV as well as significant improvement on self-compassion per SCS-SF, mindfulness skills per FFMQ-SF, and positive mental health per MHC-SF, but not on executive functioning per BRIEF-A or general functioning per OQ 45.2.

- Over 6-month follow-up, there continued to be significant improvement in CAARS-INV, CAARS-S:SV, mindfulness skills, self-compassion, and positive mental health in the MBCT plus TAU group compared to TAU. The difference in executive functioning (BRIEF-A) also became significant over time.

Conclusions/limitations

- MBCT plus TAU appears to be effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, both from a clinician-rated and self-reported perspective, with improvements lasting up to 6 months.

- There were also improvements in mindfulness, self-compassion, and positive mental health posttreatment in the MBCT plus TAU group, with improvement in executive functioning seen over the follow-up periods.

- Limitations: The sample was drawn solely from a Dutch population and did not assess the success of blinding.

Continue to: #4

4. Selaskowski B, Steffens M, Schulze M, et al. Smartphone-assisted psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114802. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114802

Managing adult ADHD can include PE, but few studies have reviewed the effectiveness of formal clinical PE. PE is “systemic, didactic-psychotherapeutic interventions, which are adequate for informing patients and their relatives about the illness and its treatment, facilitating both an understanding and personally responsible handling of the illness and supporting those afflicted in coping with the disorder.”19 Selaskowski et al11 investigated the feasibility of using smartphone-assisted PE (SAP) for adults diagnosed with ADHD.

Study design

- Participants were 60 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD. They were required to have a working comprehension of the German language and access to an Android-powered smartphone.

- Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, severe affective disorder, severe neurologic disorder, or initial use or dose change of ADHD medications 2 weeks prior to baseline.

- Participants were randomized to SAP (n = 30) or brochure-assisted PE (BAP) (n = 30). The demographics at baseline were mostly balanced between the groups except for substance abuse (5 in the SAP group vs 0 in the BAP group; P = .022).

- The primary outcome was severity of total ADHD symptoms, which was assessed by blinded evaluations conducted at baseline (T0) and after 8 weekly PE sessions (T1).

- Secondary outcomes included dropout rates, improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by the German BDI-II, improvement in functional impairment as measured by the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale (WFIRS), homework performed, attendance, and obtained PE knowledge.

- Both groups attended 8 weekly 1-hour PE group sessions led by 2 therapists and comprised of 10 participants.

Outcomes

- Only 43 of the 60 initial participants completed the study; 24 in the SAP group and 19 in the BAP group.

- The SAP group experienced a significant symptom improvement of 33.4% from T0 to T1 compared to the BAP group, which experienced a symptom improvement of 17.3% (P = .019).

- ADHD core symptoms considerably decreased in both groups. There was no significant difference between groups (P = .74).

- SAP dramatically improved inattention (P = .019), improved impulsivity (P = .03), and increased completed homework (P < .001), compared to the BAP group.

- There was no significant difference in correctly answered quiz questions or in BDI-II or WFIRS scores.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both SAP and BAP appear to be effective methods for PE, but patients who participated in SAP showed greater improvements than those who participated in BAP.

- Limitations: This study lacked a control intervention that was substantially different from SAP and lacked follow-up. The sample was a mostly German population, participants were required to have smartphone access beforehand, and substance abuse was more common in the SAP group.

Continue to: #5

5. Pan MR, Huang F, Zhao MJ, et al. A comparison of efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and CBT combined with medication in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:23-33. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.040

CBT has demonstrated long-term benefit for the core symptoms of ADHD, comorbid symptoms (anxiety and depression), and social functioning. For ADHD, pharmacotherapies have a bottom-up effect where they increase neurotransmitter concentration, leading to an effect in the prefrontal lobe, whereas psychotherapies affect behavior-related brain activity in the prefrontal lobes, leading to the release of neurotransmitters. Pan et al12 compared the benefits of CBT plus medication (CBT + M) to CBT alone on core ADHD symptoms, social functioning, and comorbid symptoms.

Study design

- The sample consisted of 124 participants age >18 who had received a diagnosis of adult ADHD according to DSM-IV via Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview and were either outpatients at Peking University Sixth Hospital or participants in a previous RCT (Huang et al20).

- Exclusion criteria included organic mental disorders, high suicide risk in those with major depressive disorder, acute BD episode requiring medication or severe panic disorder or psychotic disorder requiring medication, pervasive developmental disorder, previous or current involvement in other psychological therapies, IQ <90, unstable physical conditions requiring medical treatment, attending <7 CBT sessions, or having serious adverse effects from medication.

- Participants received CBT + M (n = 57) or CBT alone (n = 67); 40 (70.18%) participants in the CBT + M group received methylphenidate hydrochloride controlled-release tablets (average dose 27.45 ± 9.97 mg) and 17 (29.82%) received atomoxetine hydrochloride (average dose 46.35 ± 20.09 mg). There were no significant demographic differences between groups.

- CBT consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour sessions (8 to 12 participants in each group) that were led by 2 trained psychiatrist therapists and focused on behavioral and cognitive strategies.

- Participants in the CBT alone group were drug-naïve and those in CBT + M group were stable on medications.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) score from baseline to Week 12.

- Secondary outcomes included Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-Esteem Scale (SES), executive functioning (BRIEF-A), and quality of life (World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief version [WHOQOL-BREF]).

Outcomes

- ADHD-RS total, impulsiveness-hyperactivity subscale, and inattention subscale scores significantly improved in both groups (P < .01). The improvements were greater in the CBT + M group compared to the CBT-only group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

- There was no significant difference between groups in remission rate (P < .689).

- There was a significant improvement in SAS, SES, and SDS scores in both groups (P < .01).

- In terms of the WHOQOL-BREF, the CBT + M group experienced improvements only in the psychological and environmental domains, while the CBT-only group significantly improved across the board. The CBT-only group experienced greater improvement in the physical domain (P < .01).

- Both groups displayed considerable improvements in the Metacognition Index and Global Executive Composite for BRIEF-A. The shift, self-monitor, initiate, working memory, plan/organize, task monitor, and material organization skills significantly improved in the CBT + M group. The only areas where the CBT group significantly improved were initiate, material organization, and working memory. No significant differences in BRIEF-A effectiveness were discovered.

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT is an effective treatment for improving core ADHD symptoms.

- This study was unable to establish that CBT alone was preferable to CBT + M, particularly in terms of core symptoms, emotional symptoms, or self-esteem.

- CBT + M could lead to a greater improvement in executive function than CBT alone.

- Limitations: This study used previous databases rather than RCTs. There was no placebo in the CBT-only group. The findings may not be generalizable because participants had high education levels and IQ. The study lacked follow-up after 12 weeks.

Continue to: #6

6. van Andel E, Bijlenga D, Vogel SWN, et al. Effects of chronotherapy on circadian rhythm and ADHD symptoms in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delayed sleep phase syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(2):260-269. doi:10.1080/07420528.2020.1835943

Most individuals with ADHD have a delayed circadian rhythm.21 Delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) is diagnosed when a persistently delayed circadian rhythm is not brought on by other diseases or medications. ADHD symptoms and circadian rhythm may both benefit from DSPS treatment. A 3-armed randomized clinical parallel-group trial by van Andel et al13 investigated the effects of chronotherapy on ADHD symptoms and circadian rhythm.

Study design

- Participants were Dutch-speaking individuals age 18 to 55 who were diagnosed with ADHD and DSPS. They were randomized to receive melatonin 0.5 mg/d (n = 17), placebo (n = 17), or melatonin 0.5 mg/d plus 30 minutes of timed morning bright light therapy (BLT) (n = 15) daily for 3 weeks. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups except that the melatonin plus BLT group had higher use of oral contraceptives (P = .007).

- This study was completed in the Netherlands with participants from an outpatient adult ADHD clinic.

- Exclusion criteria included epilepsy, psychotic disorders, anxiety or depression requiring acute treatment, alcohol intake >15 units/week in women or >21 units/week in men, ADHD medications, medications affecting sleep, use of drugs, mental retardation, amnestic disorder, dementia, cognitive dysfunction, crossed >2 time zones in the 2 weeks prior to the study, shift work within the previous month, having children disturbing sleep, glaucoma, retinopathy, having BLT within the previous month, pregnancy, lactation, or trying to conceive.

- The study consisted of 3-armed placebo-controlled parallel groups in which 2 were double-blind (melatonin group and placebo group).

- During the first week of treatment, medication was taken 3 hours before dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) and later advanced to 4 and 5 hours in Week 2 and Week 3, respectively. BLT was used at 20 cm from the eyes for 30 minutes every morning between 7

am and 8am . - The primary outcome was DLMO in which radioimmunoassay was used to determine melatonin concentrations. DLMO was used as a marker for internal circadian rhythm.

- The secondary outcome was ADHD symptoms using the Dutch version of the ADHD Rating Scale-IV.

- Evaluations were conducted at baseline (T0), the conclusion of treatment (T1), and 2 weeks after the end of treatment (T2).

Outcomes

- Out of 51 participants, 2 dropped out of the melatonin plus BLT group before baseline, and 3 dropped out of the placebo group before T1.

- At baseline, the average DLMO was 11:43

pm ± 1 hour and 46 minutes, with 77% of participants experiencing DLMO after 11pm . Melatonin advanced DLMO by 1 hour and 28 minutes (P = .001) and melatonin plus BLT had an advance of 1 hour and 58 minutes (P < .001). DLMO was unaffected by placebo. - The melatonin group experienced a 14% reduction in ADHD symptoms (P = .038); the placebo and melatonin plus BLT groups did not experience a reduction.

- DLMO and ADHD symptoms returned to baseline 2 weeks after therapy ended.

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with DSPS and ADHD, low-dose melatonin can improve internal circadian rhythm and decrease ADHD symptoms.

- Melatonin plus BLT was not effective in improving ADHD symptoms or advancing DLMO.

- Limitations: This study used self-reported measures for ADHD symptoms. The generalizability of the findings is limited because the exclusion criteria led to minimal comorbidity. The sample was comprised of a mostly Dutch population.

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional impairment.1 ADHD begins in childhood, continues into adulthood, and has negative consequences in many facets of adult patients’ lives, including their careers, daily functioning, and interpersonal relationships.2 According to the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence’s recommendations, both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are advised for patients with ADHD.3 Although various pharmacotherapies are advised as first-line treatments for ADHD, they are frequently linked to unfavorable adverse effects, partial responses, chronic residual symptoms, high dropout rates, and issues with addiction.4 As a result, there is a need for evidence-based nonpharmacologic therapies.

In a systematic review, Nimmo-Smith et al5 found that certain nonpharmacologic treatments can be effective in helping patients with ADHD manage their illness. In clinical and cognitive assessments of ADHD, a recent meta-analysis found that noninvasive brain stimulation had a small but significant effect.6 Some evidence suggests that in addition to noninvasive brain stimulation, other nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation (PE), mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and chronotherapy, can be effective as an adjunct treatment to pharmacotherapy, and possibly as monotherapy.

Part 1 of this 2-part article reviewed 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years.7 Part 2 analyzes 6 RCTs of nonpharmacologic treatments for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table8-13).

1. Leffa DT, Grevet EH, Bau CHD, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the TUNED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(9):847-856. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2055

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) uses noninvasive, low-intensity electrical current on the scalp to affect underlying cortical activity.14 This form of neurostimulation offers an alternative treatment option for when medications fail or are not tolerated, and can be used at home without the direct involvement of a clinician.14 tDCS as a treatment for ADHD has been increasingly researched, though many studies have been limited by short treatment periods and varied methodological approaches. In a meta-analysis, Westwood et al6 found a trend toward improvement on the function of processing speed but not on attention. Leffa et al8 examined the efficacy and safety of a 4-week course of home-based tDCS in adult patients with ADHD, specifically looking at reduction in inattention symptoms.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel, sham-controlled clinical trial evaluated 64 participants age 18 to 60 from a single center in Brazil who met DSM-5 criteria for combined or primarily inattentive ADHD.

- Inclusion criteria included an inattention score ≥21 on the clinician-administered Adult ADHD Self-report Scale version 1.1 (CASRS). This scale assesses both inattentive symptoms (CASRS-I) and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (CASRS-HI). Participants were not being treated with stimulants or agreed to undergo a 30-day washout of stimulants prior to the study.

- Exclusion criteria included current moderate to severe depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II [BDI] score >21), current moderate to severe anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI] score ≥21), diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BD) with either a manic or depressive episode in the year prior to study, diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), positive screen for substance use, unstable medical condition resulting in poor functionality, pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant within 3 months of the study, not able to use home-based equipment, history of neurosurgery, presence of ferromagnetic metal in the head or presence of implanted medical devices in head/neck region, or history of epilepsy with reported seizures in the year prior to the study.

- Participants were randomized to self-administer real or sham tDCS; the devices looked the same. Participants underwent daily 30-minute sessions using a 2-mA direct constant current for a total of 28 sessions. Sham treatment involved a 30-second ramp-up to 2-mA and a 30-second ramp-down sensation at the beginning, middle, and end of each respective session.

- The primary outcome was a change in symptoms of inattention per CASRS-I. Secondary outcomes were scores on the CASRS-HI, BDI, BAI, and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions-Adult (BRIEF-A), which evaluates executive function.

Outcomes

- A total of 53 participants used stimulant medications prior to the study and 8 required a washout. The average age was 38.3, and 53% of participants were male.

- For the 55 participants who completed 4 weeks of treatment, the mean number of sessions was 25.2 in the tDCS group and 24.8 in the sham group.

- At the end of Week 4, there was a statistically significant treatment by time interaction in CASRS-I scores in the tDCS group compared to the sham group (18.88 vs 23.63 on final CASRS-I scores; P < .001).

- There were no statistically significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes.

Conclusions/limitations

- This study showed the benefits of 4 weeks of home-based tDCS for managing inattentive symptoms in adults with ADHD. The authors noted that extended treatment of tDCS may incur greater benefit, as this study used a longer treatment course compared to others that have used a shorter duration of treatment (ie, days instead of weeks). Additionally, this study placed the anodal electrode over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) vs over the left DLPFC, because there may be a decrease in activation in the right DLPFC in adults with ADHD undergoing attention tasks.15

- This study also showed that home-based tDCS can be an easier and more accessible way for patients to receive treatment, as opposed to needing to visit a health care facility.

- Limitations: The dropout rate (although only 2 of 7 participants who dropped out of the active group withdrew due to adverse events), lack of remote monitoring of patients, and restrictive inclusion criteria limit the generalizability of these findings. Additionally, 3 patients in the tDCS group and 7 in the sham group were taking psychotropic medications for anxiety or depression.

Continue to: #2

2. Hoxhaj E, Sadohara C, Borel P, et al. Mindfulness vs psychoeducation in adult ADHD: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(4):321-335. doi:10.1007/s00406-018-0868-4

Previous research has shown that using mindfulness-based approaches can improve ADHD symptoms.16,17 Hoxhaj et al9 looked at the effectiveness of mindfulness awareness practices (MAP) for alleviating ADHD symptoms.

Study design

- This RCT enrolled 81 adults from a German medical center who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD, were not taking any ADHD medications, and had not undergone any psychotherapeutic treatments in the last 3 months. Participants were randomized to receive MAP (n = 41) or PE (n = 40).

- Exclusion criteria included having a previous diagnosis of schizophrenia, BD I, active substance dependence, ASD, suicidality, self-injurious behavior, or neurologic disorders.

- The MAP group underwent 8 weekly 2.5-hour sessions, plus homework involving meditation and other exercises. The PE group was given information regarding ADHD and management options, including organization and stress management skills.

- Patients were assessed 2 weeks before treatment (T1), at the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- The primary outcome was the change in the blind-observer rated Conner’s Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) inattention/memory scales from T1 to T2.

- Secondary outcomes included the other CAARS subscales, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the BDI, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ).

Outcomes

- Baseline demographics did not differ between groups other than the MAP group having a significantly higher IQ than the PE group. However, this difference resolved after the final sample was analyzed, as there were 2 dropouts and 7 participants lost to follow-up in the MAP group and 4 dropouts and 4 participants lost to follow-up in the PE group.

- There was no significant difference between the groups in the primary outcome of observer-rated CAARS inattention/memory subscale scores, or other ADHD symptoms per the CAARS.

- However, there was a significant difference within each group on all ADHD subscales of the observer-rated CAARS at T2. Persistent, significant differences were noted for the observer-rated CAARS subscales of self-concept and DSM-IV Inattentive Symptoms, and all CAARS self-report scales to T3.

- Compared to the PE group, there was a significantly larger improvement in the MAP group on scores of the mindfulness parameters of observation and nonreactivity to inner experience.

- There were significant improvements regarding depression per the BDI and global severity per the BSI in both treatment groups, with no differences between the groups.

- At T3, in the MAP group, 3 patients received methylphenidate, 1 received atomoxetine, and 1 received antidepressant medication. In the PE group, 2 patients took methylphenidate, and 2 participants took antidepressants.

- There was a significant difference regarding sex and response, with men experiencing less overall improvement than women.

Conclusions/limitations

- MAP was not superior to PE in terms of changes on CAARS scores, although within each group, both therapies showed improvement over time.

- While there may be gender-specific differences in processing information and coping strategies, future research should examine the differences between men and women with different therapeutic approaches.

- Limitations: This study did not employ a true placebo but instead had 2 active arms. Generalizability is limited due to a lack of certain comorbidities and use of medications.

Continue to: #3

3. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65. doi:10.1017/S0033291718000429

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a form of psychotherapy that combines mindfulness with the principles of CBT. Hepark et al18 found benefits of MBCT for reducing ADHD symptoms. In a larger, multicenter, single-blind RCT, Janssen et al10 reviewed the efficacy of MBCT compared to treatment as usual (TAU).

Study design

- A total of 120 participants age ≥18 who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were recruited from Dutch clinics and advertisements and randomized to receive MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU alone (n = 60). There were no significant demographic differences between groups at baseline.

- Exclusion criteria included active depression with psychosis or suicidality, active manic episode, tic disorder with vocal tics, ASD, learning or other cognitive impairments, borderline or antisocial personality disorder, substance dependence, or previous participation in MBCT or other mindfulness-based interventions. Participants also had to be able to complete the questionnaires in Dutch.

- Blinded evaluations were conducted at baseline (T0), at the completion of therapy (T1), 3 months after the completion of therapy (T2), and 6 months after the completion of therapy (T3).

- MBCT included 8 weekly, 2.5-hour sessions and a 6-hour silent session between the sixth and seventh sessions. Patients participated in various meditation techniques with the addition of PE, CBT, and group discussions. They were also instructed to practice guided exercises 6 days/week, for approximately 30 minutes/day.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD symptoms as assessed by the investigator-rated CAARS (CAARS-INV) at T1.

- Secondary outcomes included change in scores on the CAARS: Screening Version (CAARS-S:SV), BRIEF-A, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF), Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF), Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF), and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ 45.2).

Outcomes

- In the MBCT group, participants who dropped out (n = 9) were less likely to be using ADHD medication at baseline than those who completed the study.

- At T1, the MBCT plus TAU group had significantly less ADHD symptoms on CAARS-INV compared to TAU (d = 0.41, P = .004), with more participants in the MBCT plus TAU group experiencing a symptom reduction ≥30% (24% vs 7%, P = .001) and remission (P = .039).

- The MBCT plus TAU group also had a significant reduction in scores on CAARS-S:SV as well as significant improvement on self-compassion per SCS-SF, mindfulness skills per FFMQ-SF, and positive mental health per MHC-SF, but not on executive functioning per BRIEF-A or general functioning per OQ 45.2.

- Over 6-month follow-up, there continued to be significant improvement in CAARS-INV, CAARS-S:SV, mindfulness skills, self-compassion, and positive mental health in the MBCT plus TAU group compared to TAU. The difference in executive functioning (BRIEF-A) also became significant over time.

Conclusions/limitations

- MBCT plus TAU appears to be effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, both from a clinician-rated and self-reported perspective, with improvements lasting up to 6 months.

- There were also improvements in mindfulness, self-compassion, and positive mental health posttreatment in the MBCT plus TAU group, with improvement in executive functioning seen over the follow-up periods.

- Limitations: The sample was drawn solely from a Dutch population and did not assess the success of blinding.

Continue to: #4

4. Selaskowski B, Steffens M, Schulze M, et al. Smartphone-assisted psychoeducation in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114802. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114802

Managing adult ADHD can include PE, but few studies have reviewed the effectiveness of formal clinical PE. PE is “systemic, didactic-psychotherapeutic interventions, which are adequate for informing patients and their relatives about the illness and its treatment, facilitating both an understanding and personally responsible handling of the illness and supporting those afflicted in coping with the disorder.”19 Selaskowski et al11 investigated the feasibility of using smartphone-assisted PE (SAP) for adults diagnosed with ADHD.

Study design

- Participants were 60 adults age 18 to 65 who met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD. They were required to have a working comprehension of the German language and access to an Android-powered smartphone.

- Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, severe affective disorder, severe neurologic disorder, or initial use or dose change of ADHD medications 2 weeks prior to baseline.

- Participants were randomized to SAP (n = 30) or brochure-assisted PE (BAP) (n = 30). The demographics at baseline were mostly balanced between the groups except for substance abuse (5 in the SAP group vs 0 in the BAP group; P = .022).

- The primary outcome was severity of total ADHD symptoms, which was assessed by blinded evaluations conducted at baseline (T0) and after 8 weekly PE sessions (T1).

- Secondary outcomes included dropout rates, improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by the German BDI-II, improvement in functional impairment as measured by the Weiss Functional Impairment Scale (WFIRS), homework performed, attendance, and obtained PE knowledge.

- Both groups attended 8 weekly 1-hour PE group sessions led by 2 therapists and comprised of 10 participants.

Outcomes

- Only 43 of the 60 initial participants completed the study; 24 in the SAP group and 19 in the BAP group.

- The SAP group experienced a significant symptom improvement of 33.4% from T0 to T1 compared to the BAP group, which experienced a symptom improvement of 17.3% (P = .019).

- ADHD core symptoms considerably decreased in both groups. There was no significant difference between groups (P = .74).

- SAP dramatically improved inattention (P = .019), improved impulsivity (P = .03), and increased completed homework (P < .001), compared to the BAP group.

- There was no significant difference in correctly answered quiz questions or in BDI-II or WFIRS scores.

Conclusions/limitations

- Both SAP and BAP appear to be effective methods for PE, but patients who participated in SAP showed greater improvements than those who participated in BAP.

- Limitations: This study lacked a control intervention that was substantially different from SAP and lacked follow-up. The sample was a mostly German population, participants were required to have smartphone access beforehand, and substance abuse was more common in the SAP group.

Continue to: #5

5. Pan MR, Huang F, Zhao MJ, et al. A comparison of efficacy between cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and CBT combined with medication in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:23-33. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.040

CBT has demonstrated long-term benefit for the core symptoms of ADHD, comorbid symptoms (anxiety and depression), and social functioning. For ADHD, pharmacotherapies have a bottom-up effect where they increase neurotransmitter concentration, leading to an effect in the prefrontal lobe, whereas psychotherapies affect behavior-related brain activity in the prefrontal lobes, leading to the release of neurotransmitters. Pan et al12 compared the benefits of CBT plus medication (CBT + M) to CBT alone on core ADHD symptoms, social functioning, and comorbid symptoms.

Study design

- The sample consisted of 124 participants age >18 who had received a diagnosis of adult ADHD according to DSM-IV via Conner’s Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview and were either outpatients at Peking University Sixth Hospital or participants in a previous RCT (Huang et al20).

- Exclusion criteria included organic mental disorders, high suicide risk in those with major depressive disorder, acute BD episode requiring medication or severe panic disorder or psychotic disorder requiring medication, pervasive developmental disorder, previous or current involvement in other psychological therapies, IQ <90, unstable physical conditions requiring medical treatment, attending <7 CBT sessions, or having serious adverse effects from medication.

- Participants received CBT + M (n = 57) or CBT alone (n = 67); 40 (70.18%) participants in the CBT + M group received methylphenidate hydrochloride controlled-release tablets (average dose 27.45 ± 9.97 mg) and 17 (29.82%) received atomoxetine hydrochloride (average dose 46.35 ± 20.09 mg). There were no significant demographic differences between groups.

- CBT consisted of 12 weekly 2-hour sessions (8 to 12 participants in each group) that were led by 2 trained psychiatrist therapists and focused on behavioral and cognitive strategies.

- Participants in the CBT alone group were drug-naïve and those in CBT + M group were stable on medications.

- The primary outcome was change in ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) score from baseline to Week 12.

- Secondary outcomes included Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-Esteem Scale (SES), executive functioning (BRIEF-A), and quality of life (World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief version [WHOQOL-BREF]).

Outcomes

- ADHD-RS total, impulsiveness-hyperactivity subscale, and inattention subscale scores significantly improved in both groups (P < .01). The improvements were greater in the CBT + M group compared to the CBT-only group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

- There was no significant difference between groups in remission rate (P < .689).

- There was a significant improvement in SAS, SES, and SDS scores in both groups (P < .01).

- In terms of the WHOQOL-BREF, the CBT + M group experienced improvements only in the psychological and environmental domains, while the CBT-only group significantly improved across the board. The CBT-only group experienced greater improvement in the physical domain (P < .01).

- Both groups displayed considerable improvements in the Metacognition Index and Global Executive Composite for BRIEF-A. The shift, self-monitor, initiate, working memory, plan/organize, task monitor, and material organization skills significantly improved in the CBT + M group. The only areas where the CBT group significantly improved were initiate, material organization, and working memory. No significant differences in BRIEF-A effectiveness were discovered.

Conclusions/limitations

- CBT is an effective treatment for improving core ADHD symptoms.

- This study was unable to establish that CBT alone was preferable to CBT + M, particularly in terms of core symptoms, emotional symptoms, or self-esteem.

- CBT + M could lead to a greater improvement in executive function than CBT alone.

- Limitations: This study used previous databases rather than RCTs. There was no placebo in the CBT-only group. The findings may not be generalizable because participants had high education levels and IQ. The study lacked follow-up after 12 weeks.

Continue to: #6

6. van Andel E, Bijlenga D, Vogel SWN, et al. Effects of chronotherapy on circadian rhythm and ADHD symptoms in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and delayed sleep phase syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(2):260-269. doi:10.1080/07420528.2020.1835943