User login

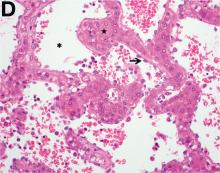

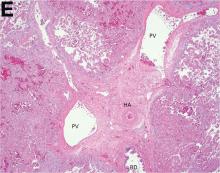

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

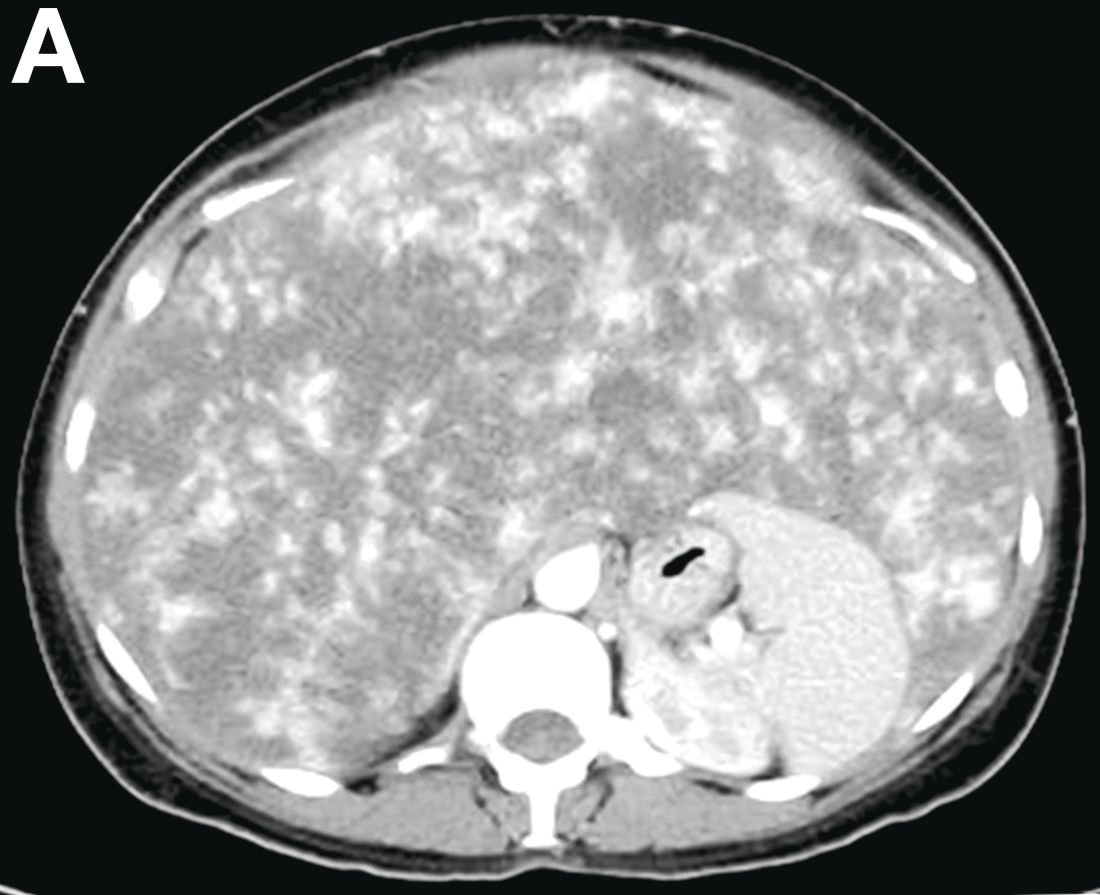

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

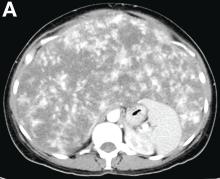

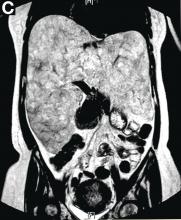

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

Over the next 6 months she developed progressive liver failure (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 34), and required several hospitalizations for worsening abdominal pain and debility. Despite the high risk of complications, she agreed to pursue a liver transplant. During the course of surgery, there was significant hemorrhage from tearing of the portal vein (PV) anastomosis and surrounding areas; despite all resuscitative efforts, she went into cardiac arrest and died. The sections of explanted liver revealed soft, spongy parenchyma with blood-filled cyst-like cavities measuring 1-6 mm in diameter (Figure F). The entire liver was affected by vascular malformations (VMs) and there was no evidence of malignancy. On elastin stain, the elastic lamina of the vascular wall appeared thin and disrupted; D2-40 and GLUT1 antibody stains were negative. The hilar PV wall thickness was variable with areas of intramural loose connective tissue separating smooth muscle bundles. This made the PV very friable, which, along with coagulopathy, was the likely cause of uncontrollable intraoperative bleeding. These findings indicate that the vascular spaces were derived from malformation of PV branches.

VMs are rare liver lesions that can be idiopathic or associated with cirrhosis, traumatic injuries, and syndromes such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Although not always apparent, VMs are present at birth and grow proportionally with the patient’s age.1 They are usually solitary or multifocal, but rare cases of diffuse hepatic involvement have been reported.2 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of diffuse hepatic VM in an adult with no evidence of extrahepatic involvement. Diffuse hepatic VM may be confused with diffuse hepatic hemangiomatosis, another rare condition in adults characterized by replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with hemangiomatous lesions, but differs in that it is a vascular tumor and not VM. While vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation, VMs develop from abnormal vascular morphogenesis, and are named after the vascular element they closely resemble, namely, capillary, venous, or arterial malformations. Although these are 2 distinct entities, the terms hemangioma and VM have been used indiscriminately and interchangeably in the literature to describe vascular anomalies.1 Most hepatic VMs are asymptomatic, but depending on the extent of involvement, patients may develop high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease.3 Despite extensive liver involvement, our patient did not manifest shunt physiology. The radiographic findings were nonspecific but indicative of diffuse vascular lesions in the liver. Histologic characteristics include dilated, irregular vascular channels, lined by a flat endothelium, separated by liver parenchyma and fibrovascular tissue.2 Histochemical stains for collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle are often used to further characterize VMs. Therapeutic options in focal VMs include sclerotherapy, embolization, and surgical resection. In severe cases with progressive hepatic failure, liver transplantation may be the only feasible option. A case of successful living donor liver transplant in a 14-year-old with VMs involving liver and colon has been described in literature.3 Unfortunately, our patient did not survive the surgery. More reports using accurate terminology to describe hepatic vascular anomalies are needed for further understanding of this rare yet fatal disease.

References

1. George A., Mani V., Noufal A. Update on the classification of hemangioma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S117-20.

2. Sato K., Amanuma M., Fukusato T., et al. Diffuse hepatic vascular malformations with right aortic arch. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1094-5.

3. Hatanaka M., Nakazawa A., Nakano N., et al. Successful living donor liver transplantation for giant extensive venous malformation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:E152-6.

A 50-year-old Guyanese woman was found to have abnormal liver tests on routine testing with total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL (normal, 0.2–1.2); alkaline phosphatase, 189 U/L (normal, 47–154); aspartate transaminase, 57 U/L (normal, 11–42); and alanine transaminase, 33 U/L (normal, 0–20).

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151[6]:1081-2).