User login

As a family physician (FP), you are well positioned to optimize the quality of life of advanced cancer patients as they decline and approach death. You can help them understand their evolving prognosis so that treatment goals can be adjusted, and you can ensure that hospice is implemented early to improve the end-of-life experience. This practical review will help you to provide the best care possible for these patients.

Family physicians can fill a care gap

The term cancer survivor describes a patient who has completed initial cancer treatment. Within this population, many have declining health and ultimately succumb to their disease. There were 16.9 million cancer survivors in the United States as of January 1, 2019,1 with 53% likely to experience significant symptoms and disability.2 More than 600,000 American cancer survivors will die in 2019.3

In 2011, the Commission on Cancer mandated available outpatient palliative care services at certified cancer centers.4 Unfortunately, current palliative care resources fall far short of expected needs. A 2010 estimate of required hospice and palliative care physicians demonstrated a staffing gap of more than 50% among those providing outpatient services.5 The shortage continues,6 and many cancer patients will look to their FP for supportive care.

FPs, in addition to easing symptoms and adverse effects of medication, can educate patients and families about their disease and prognosis. By providing longitudinal care, FPs can identify critical health declines that oncologists, patients, and families often overlook. FPs can also readily appreciate decline, guide patients toward their care goals, and facilitate comfort care—including at the end of life.

Early outpatient palliative care improves quality of life and patient satisfaction. It also may improve survival time and ward off depression.7,8 Some patients and providers resist palliative care due to a misconception that it requires abandoning treatment.9 Actually, palliative care can be given in concert with all active treatments. Many experts recommend a name change from “palliative care” to “supportive care” to dispel this misconception.10

Estimate prognosis using the “surprise question”

Several algorithms are available—using between 2 and 13 patient parameters—to estimate advanced cancer survival. Most of these algorithms are designed to identify the last months or weeks of life, but their utility to predict death within these periods is limited.11

The “surprise question” may be the most valuable prognostic test for primary care. In this test, the physician asks him- or herself: Would I be surprised if this patient died in 1 year? Researchers found that when primary care physicians answered No, their patient was 4 times more likely to die within the year than when they answered Yes.12 This test has a positive predictive value of 20% and a negative predictive value of 95%, making it valuable in distinguishing patients with longer life expectancy.12 Although it overidentifies at-risk patients, the "surprise question" is a simple and sensitive tool for defining prognosis.

Continue to: Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

For patients who likely have more than a year to live, the focus is on symptom management and preparation for future decline. Initiate and facilitate discussions about end-of-life topics. Cancer survivors are often open to discussions on these topics, which include advanced directives, home health aides, and hospice.13 Patients can set specific goals for their remaining time, such as engaging in travel, personal projects, or special events. Cancer patients have better end-of-life experiences and families have improved mental health after these discussions.14 Although cancer patients are more likely than other terminal patients to have end-of-life discussions, fewer than 40% ever do.15

Address distressing symptoms with a focus on maintaining function. More than 50% of advanced cancer patients experience fatigue, weakness, pain, weight loss, and anorexia,16 and up to 60% experience psychological distress.17 Deprescribing most preventive medications is recommended with transition to symptomatic treatment.18

Priorities for patients with less than a year to live

For patients who may have less than a year to live, focus shifts to their wishes for the time remaining and priorities for the dying process. Most patients start out with prognostic views more optimistic than those of their physicians, but this gap narrows after end-of-life discussions.19,20 Patients with incurable cancer are less likely to choose aggressive therapy if they believe their 6-month survival probability is less than 90%.21 Honest conversations, with best- and worst-case scenarios, are important to patients and families, and should occur while the patient is well enough to participate and set goals.22

In the last months of life, opioids become the primary treatment for pain and air hunger. As function declines, concerns about such adverse effects as falls and confusion decrease. Opioids have been shown to be most effective over the course of 4 weeks, and avoiding their use in earlier stages may increase their efficacy at the end of life.23

Hospice benefit—more comfort, with limitations

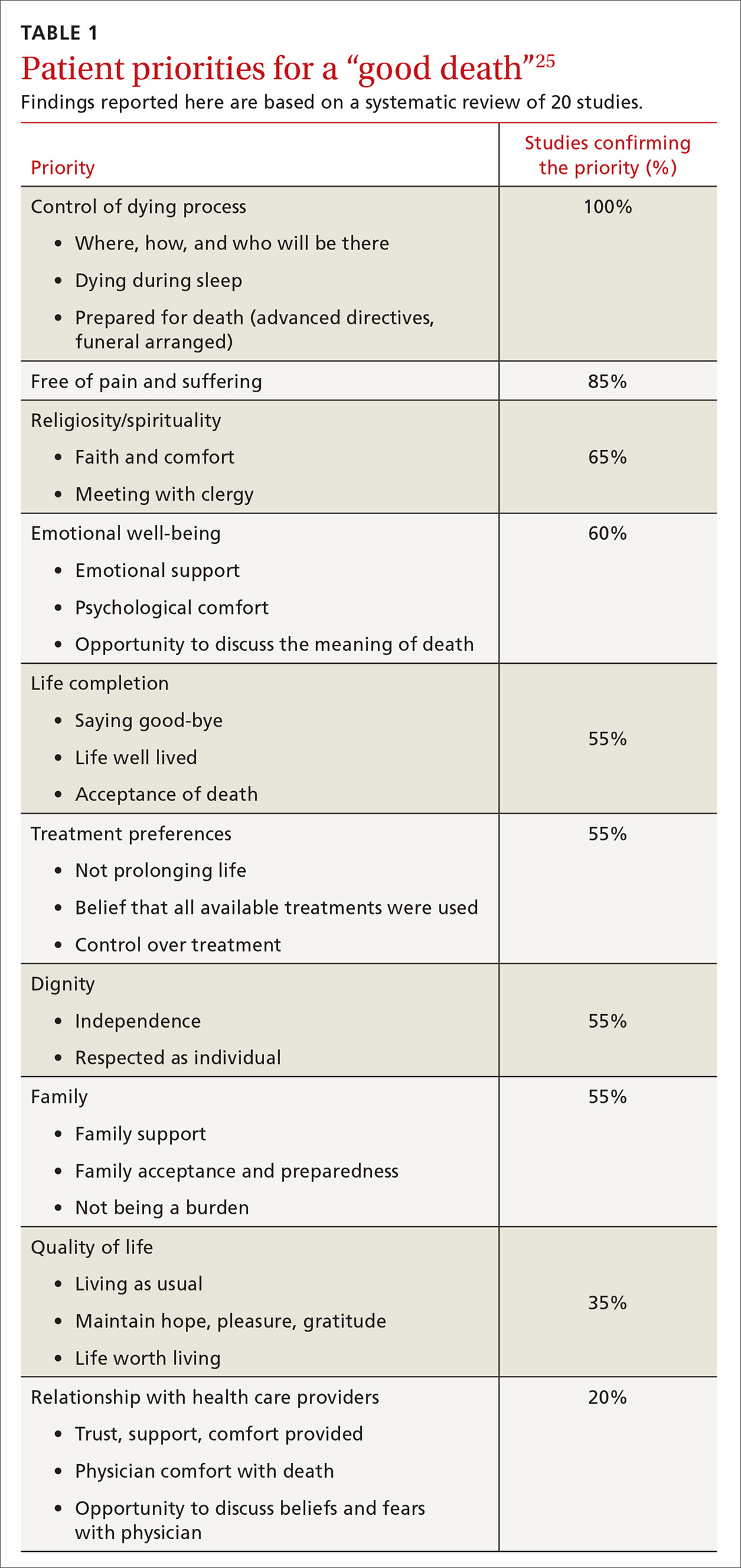

Hospice care consists of services administered by nonprofit and for-profit entities covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and many private insurers.24 Hospice strives to allow patients to approach death in comfort, meeting their goal of a “good death.” A recent literature review identified 4 aspects of a good death that terminally ill patients and their families considered most important: control of the dying process, relief of pain, spirituality, and emotional well-being (TABLE 1).25

Continue to: Hospice use is increasing...

Hospice use is increasing, yet many enroll too late to fully benefit. While cancer patients alone are not currently tracked, the use of hospice by Medicare beneficiaries increased from 44% in 2012 to 48% in 2019.24 In 2017, the median hospice stay was 19 days.24 Unfortunately, though, just 28% of hospice-eligible patients enrolled in hospice in their last week of life.24 Without hospice, patients often receive excessive care near death. More than 6% receive aggressive chemotherapy in their last 2 weeks of life, and nearly 10% receive a life-prolonging procedure in their last month.26

Hospice care replaces standard hospital care, although patients can elect to be followed by their primary care physician.9 Most hospice services are provided as needed or continuously at the patient’s home, including assisted living facilities. And it is also offered as part of hospital care. Hospice services are interdisciplinary, provided by physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and health aides. Hospices have on-call staff to assess and treat complications, avoiding emergency hospital visits.9 And hospice includes up to 5 days respite care for family caregivers, although with a 5% copay.9 Most hospice entities run inpatient facilities for care that cannot be effectively provided at home.

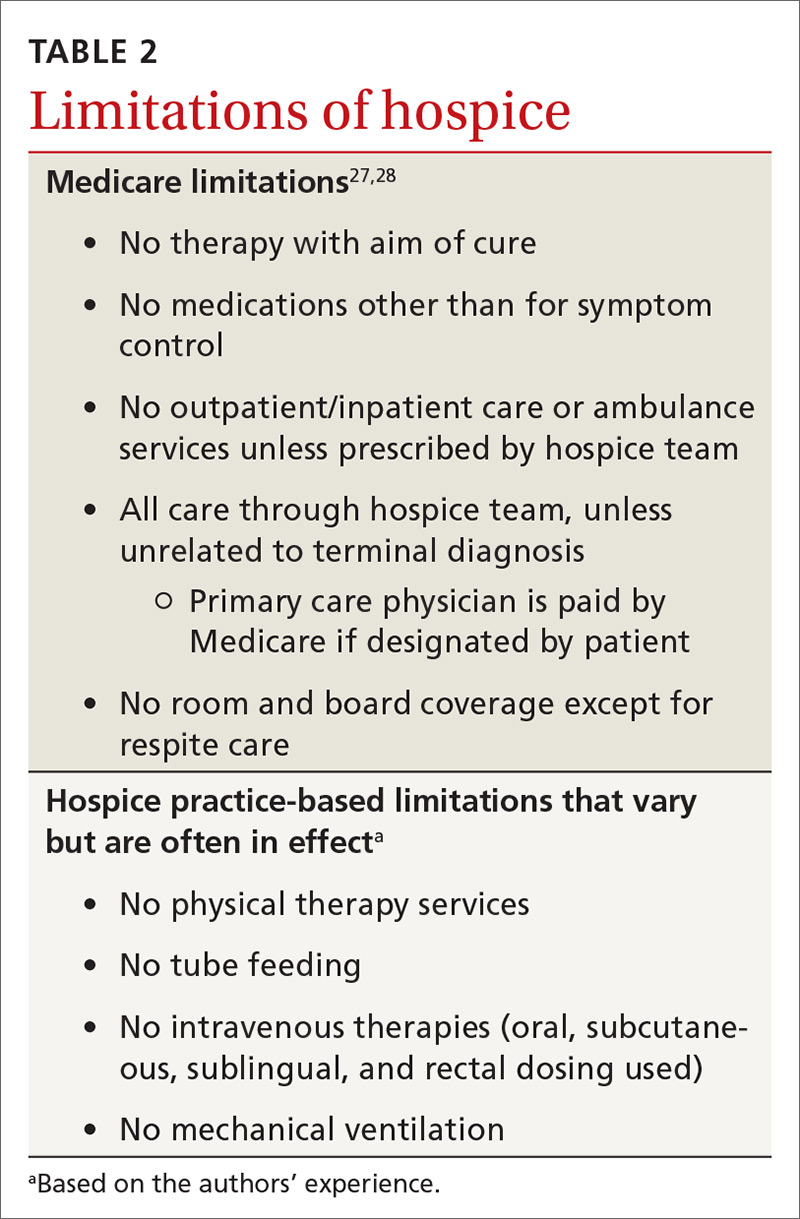

Hospice care has limitations—many set by insurance. Medicare, for example, stipulates that a primary care or hospice physician must certify the patient has a reasonable prognosis of 6 months or less and is expected to have a declining course.27 Patients who survive longer than 6 months are recertified by the same criteria every 60 days.27

Hospice patients forgo treatments aimed at curing their terminal diagnosis.28 Some hospice entities allow noncurative therapies while others do not. Hospice covers prescription medications for symptom control only, although patients can receive care unrelated to the terminal diagnosis under regular benefits.28 Hospice care practices differ from standard care in ways that may surprise patients and families (TABLE 227,28). Patients can disenroll and re-enroll in hospice as they wish.28

Symptom control in advanced cancer

General symptoms

Pain affects 64% of patients with advanced cancer.29 Evidence shows that cancer pain is often undertreated, with a recent systematic review reporting undertreated pain in 32% of patients.30 State and national chronic opioid guidelines do not restrict use for cancer pain.31 Opioids are effective in 75% of cancer patients over 1 month, but there is no evidence of benefit after this period.23 In fact, increasing evidence demonstrates that pain is likely negatively responsive to opioids over longer periods.32 Opioid adverse effects can worsen other cancer symptoms, including depression, anxiety, fatigue, constipation, hypogonadism, and cognitive dysfunction.32 Delaying opioid therapy to end of life can limit adverse effects and may preserve pain-control efficacy for the dying process.

Continue to: Most cancer pain...

Most cancer pain is partially neuropathic, so anticonvulsant and antidepressant medications can help.33 Gabapentin, pregabalin, and duloxetine are recommended based on evidence not restricted to cancer.34 Cannabinoids have been evaluated in 2 trials of cancer pain with 440 patients and showed a borderline significant reduction of pain.35

Palliative radiation therapy can sometimes reduce pain. Bone metastases pain has been studied the most, and the literature suggests that palliative radiation provides improvement for 60% of patients and complete relief to 25% of patients.36 Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for primary or metastatic lung masses reduces pain by more than 70% while improving dyspnea, hemoptysis, and cough in a majority of patients.36

Other uses of palliative radiation have varied evidence. Palliative chemotherapy has less evidence of benefit. In a recent multicenter cohort trial, chemotherapy in end-stage cancer reduced quality of life in patients with good functional status, without affecting quality of life when function was limited.37 Palliative chemotherapy may be beneficial if combined with corticosteroids or radiation therapy.38

Treatment in the last weeks of life centers on opioids; dose increases do not shorten survival.39 Cancer patients are 4 times as likely as noncancer patients to have severe or excruciating pain during the last 3 days of life.40 Narcotics can be titrated aggressively near end of life with less concern for hypotension, respiratory depression, or level of consciousness. Palliative sedation remains an option for uncontrolled pain.41

Anorexia is only a problem if quality of life is affected. Cachexia is caused by increases in cytokines more than reduced calorie intake.42 Reversible causes of reduced eating may be found, including candidiasis, dental problems, depression, or constipation. Megestrol acetate improves weight (number needed to treat = 12), although it significantly increases mortality (number needed to harm = 23), making its use controversial.43 Limited study of cannabinoids has not shown effectiveness in treating anorexia.35

Continue to: Constipation...

Constipation in advanced cancer is often related to opioid therapy, although bowel obstruction must be considered. Opioid-induced constipation affects 40% to 90% of patients on long-term treatment,44 and 5 days of opioid treatment nearly doubles gastrointestinal transit time.45 Opioid-induced constipation can be treated by adding a stimulating laxative followed by a peripheral acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist, such as subcutaneous methylnaltrexone or oral naloxegol.46 These medications are contraindicated if ileus or bowel obstruction is suspected.46

Nausea and vomiting are common in advanced cancer and have numerous causes. Approximately half of reversible causes are medication adverse effects from either chemotherapy or pain medication.47 Opioid rotation may improve symptoms.47 A suspected bowel obstruction should be evaluated by specialists; surgery, palliative chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or stenting may be required. Oncologists can best manage adverse effects of chemotherapy. For nausea and vomiting unrelated to chemotherapy, consider treating constipation and pain. Medication can also be helpful; a systemic review suggests metoclopramide works best, with some evidence supporting other dopaminergic agonists, including haloperidol.47

Fatigue. Both methylphenidate and modafinil have been studied to treat cancer-related fatigue.48 A majority of patients treated with methylphenidate reported less cancer-related fatigue at 4 weeks and wished to continue treatment.49 Modafinil demonstrated minimal improvement in fatigue.50 Sleep disorders, often due to anxiety or sleep apnea, may be a correctable cause.

Later symptoms

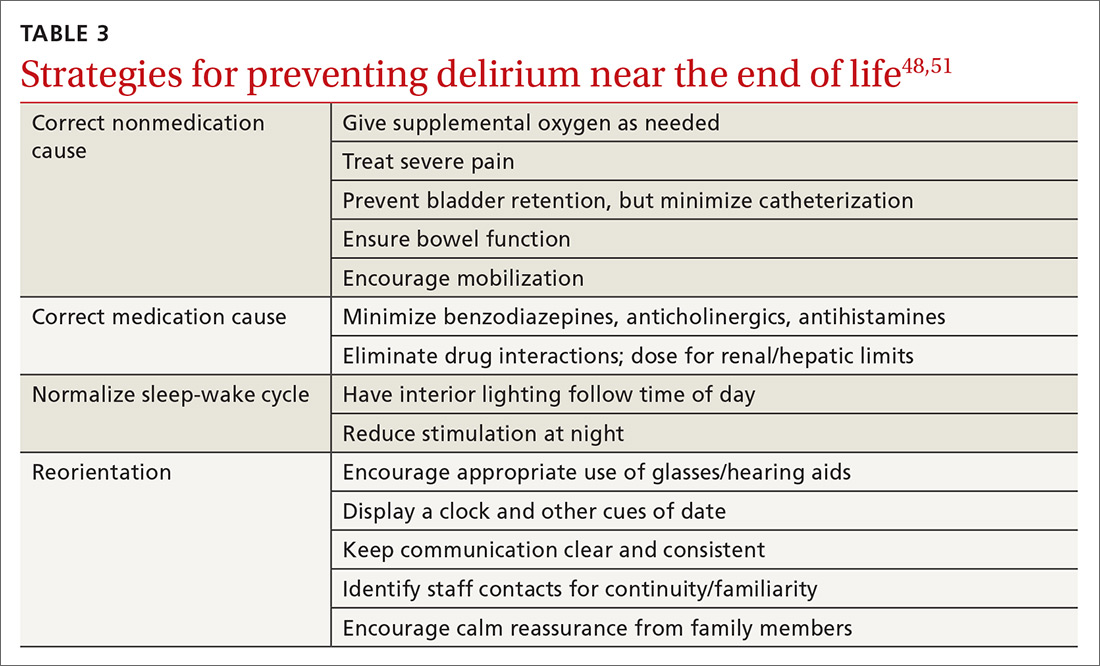

Delirium occurs in up to 90% of cancer patients near the end of life, and can signal death.51 Up to half of the delirium seen in palliative care is reversible.51 Reversible causes include uncontrolled pain, medication adverse effects, and urinary and fecal retention (TABLE 348,51). Addressing these factors reduces delirium, based on studies in postoperative patients.52 Consider opioid rotation if neurotoxicity is suspected.51

Delirium can be accompanied by agitation or decreased responsiveness.53 Agitated delirium commonly presents with moaning, facial grimacing, and purposeless repetitive movements, such as plucking bedsheets or removing clothes.51 Delirious patients without agitation have reported, following recovery, distress similar to that experienced by agitated patients.54 Caregivers are most likely to recognize delirium and often become upset. Educating family members about the frequency of delirium can lessen this distress.54

Continue to: Delirium can be treated with...

Delirium can be treated with antipsychotics; haloperidol has been most frequently studied.54 Antipsychotics are effective at reducing agitation but not at restoring cognition.55 Case reports suggest that use of atypical antipsychotics can be beneficial if adverse effects limit haloperidol dosing.56 Agitated delirium is the most frequent indication for palliative sedation.57

Dyspnea. In the last weeks, days, or hours of life, dyspnea is common and often distressing. Dyspnea appears to be multifactorial, worsened by poor control of secretions, airway hyperactivity, and lung pathologies.58 Intravenous hydration may unintentionally exacerbate dyspnea. Hospice providers generally discourage intravenous hydration because relative dehydration reduces terminal respiratory secretions (“death rattle”) and increases patient comfort.59

Some simple nonpharmacologic interventions have benefit. Oxygen is commonly employed, although multiple studies show no benefit over room air.59 Directing a handheld fan at the face does reduce dyspnea, likely by activation of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve.60

Opioids effectively treat dyspnea near the end of life with oral and parenteral dosing, but the evidence does not support nebulized opioids.61 Opioid doses required to treat dyspnea are less than those for pain and do not cause significant respiratory depression.62 If a patient taking opioids experiences dyspnea, a 25% dose increase is recommended.63

Anticholinergic medications can improve excessive airway secretions associated with dyspnea. Glycopyrrolate causes less delirium because it does not cross the blood-brain barrier, while scopolamine patches have reduced anticholinergic adverse effects, but effects are delayed until 12 hours after patch placement.64 Atropine eye drops given sublingually were effective in a small study.65

Continue to: Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation can manage intractable symptoms near the end of life. A recent systematic review suggests that palliative sedation does not shorten life.57 Sedation is most often initiated by gradual increases in medication doses.57 Midazolam is most often employed, but antipsychotics are also used.57

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, MD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4501 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; michael.arnold@usuhs.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Kristian Sanchack, MD, and James Higgins, DO, assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures-2019-2021.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2019.

2. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 2. 2019. Palliative Care. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. (Must register an account for access.) Accessed September 4, 2019.

4. American Cancer Society. New CoC accreditation standards gain strong support. www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2011/coc-standards0811. Accessed September 11, 2019.

5. Lupu D; American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899-911.

6. Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1216-1223.

7. Rabow MW, Dahlin C, Calton B, et al. New frontiers in outpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:465-474.

8. Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017:CD01129.

9. Buss MK, Rock LK, McCarthy EP. Understanding palliative care and hospice: a review for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:280-286.

10. Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:372-379.

11. Simmons CPL, McMillan DC, McWilliams K, et al. Prognostic tools in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:962-970.

12. Lakin JR, Robinson MG, Bernacki RE, et al. Estimating 1-year mortality for high-risk primary care patients using the “surprise” question. JAMA Int Med. 2016;176:1863-1865.

13. Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MH, et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psychoonchology. 2015;24:287-293.

14. Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, et al. Effects of end-of-life discussions on the mental health of bereaved family members and quality of patient death and care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:17-26.

15. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

16. Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94-104.

17. Gao W, Bennett MI, Stark D, et al. Psychological distress in cancer from survivorship to end of life: prevalence, associated factors and clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2036-2044.

18. Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:121-124.

19. Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1421-1426.

20. Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, et al. Discussions of life expectancy and changes in illness understanding in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2398-2403.

21. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709-1714.

22. Myers J. Improving the quality of end-of-life discussions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:72-76.

23. Corli O, Floriani I, Roberto A, et al. Are strong opioids equally effective and safe in the treatment of chronic cancer pain? A multicenter randomized phase IV ‘real life’ trial on the variability of response to opioids. Ann Oncolog. 2016;27:1107-1115.

24. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures. 2018. www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2019.

25. Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, et al. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:261-271.

26. Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:786-796.

27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefit Facts. www.cgsmedicare.com/hhh/education/materials/pdf/Medicare_Hospice_Benefit_Facts.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefits. www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

29. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437-1449.

30. Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4149-4154.

31. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

32. Davis MP, Mehta Z. Opioids and chronic pain: where is the balance? Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18:71.

33. Leppert W, Zajaczkowska R, Wordliczek J, et al. Pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of pain in most common locations in cancer patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;67:787-799.

34. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:162-173.

35. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

36. Jones JA, Lutz ST, Chow E. et al. Palliative radiotherapy at the end of life: a critical review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:296-310.

37. Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:778-784.

38. Kongsgaard U, Kaasa S, Dale O, et al. Palliative treatment of cancer-related pain. 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464794/. Accessed September 24, 2019.

39. Sathornviriyapong A, Nagaviroj K, Anothaisintawee T. The association between different opioid doses and the survival of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:95.

40. Steindal SA, Bredal IS. Sørbye LW, et al. Pain control at the end of life: a comparative study of hospitalized cancer and noncancer patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:771-779.

41. Maltoni M, Setola E. Palliative sedation in patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:433-441.

42. Cooper C, Burden ST, Cheng H, et al. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:99-111.

43. Ruiz Garcia V, LÓpez-Briz E, Carbonell Sanchis R, et al. Megesterol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;28:CD004310.

44. Chey WD, Webster L, Sostek M, et al. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2387-2396.

45. Poulsen JL, Nilsson M, Brock C, et al. The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:282-291.

46. Pergolizzi JV, Raffa RB, Pappagallo M, et al. Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists as treatment options for constipation in noncancer pain patients on chronic opioid therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:107-119.

47. Walsh D, Davis M, Ripamonti C, et al. 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:333-340.

48. Mücke M, Mochamat, Cuhls H, et al. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD006788.

49. Escalante CP, Meyers C, Reuben JM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, 2-period, placebo-controlled crossover trial of a sustained-release methylphenidate in the treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. Cancer J. 2014;20:8-14.

50. Hovey E, de Souza P, Marx G, et al. Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of modafinil for fatigue in patients treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1233-1242.

51. Hosker CM, Bennett MI. Delirium and agitation at the end of life. BMJ. 2016;353:i3085.

52. Mercantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:516-522.

53. Casarett DJ, Inouye SK. Diagnosis and management of delirium near the end of life. Ann Int Med. 2001;135:32-40.

54. Breitbart W, Alici Y. Agitation and delirium at the end of life: “We couldn’t manage him." JAMA. 2008;300:2898-2910.

55. Candy B, Jackson KC, Jones L, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD004770.

56. Bascom PB, Bordley JL, Lawton AJ. High-dose neuroleptics and neuroleptic rotation for agitated delirium near the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31:808-811.

57. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, et al. Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1378-1383.

58. Albert RH. End-of-life care: managing common symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:356-361.

59. Arenella C. Artificial nutrition and hydration at the end of life: beneficial or harmful? https://americanhospice.org/caregiving/artificial-nutrition-and-hydration-at-the-end-of-life-beneficial-or-harmful/ Accessed September 11, 2019.

60. Booth S, Moffat C, Burkin J, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for breathlessness. Curr Opinion Support Pall Care. 2011;5:77-86.

61. Barnes H, McDonald J, Smallwood N, et al. Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(3)CD011008.

62. Lim RB. End-of-life care in patients with advanced lung cancer. Ther Adv Resp Dis. 2016;10:455-467.

63. Kreher M. Symptom control at the end of life. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100:1111-1122.

64. Baralatei FT, Ackerman RJ. Care of patients at the end of life: management of nonpain symptoms. FP Essent. 2016;447:18-24.

65. Protus BM, Grauer PA, Kimbrel JM. Evaluation of atropine 1% ophthalmic solution administered sublingual for the management of terminal respiratory secretions. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30:388-392.

As a family physician (FP), you are well positioned to optimize the quality of life of advanced cancer patients as they decline and approach death. You can help them understand their evolving prognosis so that treatment goals can be adjusted, and you can ensure that hospice is implemented early to improve the end-of-life experience. This practical review will help you to provide the best care possible for these patients.

Family physicians can fill a care gap

The term cancer survivor describes a patient who has completed initial cancer treatment. Within this population, many have declining health and ultimately succumb to their disease. There were 16.9 million cancer survivors in the United States as of January 1, 2019,1 with 53% likely to experience significant symptoms and disability.2 More than 600,000 American cancer survivors will die in 2019.3

In 2011, the Commission on Cancer mandated available outpatient palliative care services at certified cancer centers.4 Unfortunately, current palliative care resources fall far short of expected needs. A 2010 estimate of required hospice and palliative care physicians demonstrated a staffing gap of more than 50% among those providing outpatient services.5 The shortage continues,6 and many cancer patients will look to their FP for supportive care.

FPs, in addition to easing symptoms and adverse effects of medication, can educate patients and families about their disease and prognosis. By providing longitudinal care, FPs can identify critical health declines that oncologists, patients, and families often overlook. FPs can also readily appreciate decline, guide patients toward their care goals, and facilitate comfort care—including at the end of life.

Early outpatient palliative care improves quality of life and patient satisfaction. It also may improve survival time and ward off depression.7,8 Some patients and providers resist palliative care due to a misconception that it requires abandoning treatment.9 Actually, palliative care can be given in concert with all active treatments. Many experts recommend a name change from “palliative care” to “supportive care” to dispel this misconception.10

Estimate prognosis using the “surprise question”

Several algorithms are available—using between 2 and 13 patient parameters—to estimate advanced cancer survival. Most of these algorithms are designed to identify the last months or weeks of life, but their utility to predict death within these periods is limited.11

The “surprise question” may be the most valuable prognostic test for primary care. In this test, the physician asks him- or herself: Would I be surprised if this patient died in 1 year? Researchers found that when primary care physicians answered No, their patient was 4 times more likely to die within the year than when they answered Yes.12 This test has a positive predictive value of 20% and a negative predictive value of 95%, making it valuable in distinguishing patients with longer life expectancy.12 Although it overidentifies at-risk patients, the "surprise question" is a simple and sensitive tool for defining prognosis.

Continue to: Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

For patients who likely have more than a year to live, the focus is on symptom management and preparation for future decline. Initiate and facilitate discussions about end-of-life topics. Cancer survivors are often open to discussions on these topics, which include advanced directives, home health aides, and hospice.13 Patients can set specific goals for their remaining time, such as engaging in travel, personal projects, or special events. Cancer patients have better end-of-life experiences and families have improved mental health after these discussions.14 Although cancer patients are more likely than other terminal patients to have end-of-life discussions, fewer than 40% ever do.15

Address distressing symptoms with a focus on maintaining function. More than 50% of advanced cancer patients experience fatigue, weakness, pain, weight loss, and anorexia,16 and up to 60% experience psychological distress.17 Deprescribing most preventive medications is recommended with transition to symptomatic treatment.18

Priorities for patients with less than a year to live

For patients who may have less than a year to live, focus shifts to their wishes for the time remaining and priorities for the dying process. Most patients start out with prognostic views more optimistic than those of their physicians, but this gap narrows after end-of-life discussions.19,20 Patients with incurable cancer are less likely to choose aggressive therapy if they believe their 6-month survival probability is less than 90%.21 Honest conversations, with best- and worst-case scenarios, are important to patients and families, and should occur while the patient is well enough to participate and set goals.22

In the last months of life, opioids become the primary treatment for pain and air hunger. As function declines, concerns about such adverse effects as falls and confusion decrease. Opioids have been shown to be most effective over the course of 4 weeks, and avoiding their use in earlier stages may increase their efficacy at the end of life.23

Hospice benefit—more comfort, with limitations

Hospice care consists of services administered by nonprofit and for-profit entities covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and many private insurers.24 Hospice strives to allow patients to approach death in comfort, meeting their goal of a “good death.” A recent literature review identified 4 aspects of a good death that terminally ill patients and their families considered most important: control of the dying process, relief of pain, spirituality, and emotional well-being (TABLE 1).25

Continue to: Hospice use is increasing...

Hospice use is increasing, yet many enroll too late to fully benefit. While cancer patients alone are not currently tracked, the use of hospice by Medicare beneficiaries increased from 44% in 2012 to 48% in 2019.24 In 2017, the median hospice stay was 19 days.24 Unfortunately, though, just 28% of hospice-eligible patients enrolled in hospice in their last week of life.24 Without hospice, patients often receive excessive care near death. More than 6% receive aggressive chemotherapy in their last 2 weeks of life, and nearly 10% receive a life-prolonging procedure in their last month.26

Hospice care replaces standard hospital care, although patients can elect to be followed by their primary care physician.9 Most hospice services are provided as needed or continuously at the patient’s home, including assisted living facilities. And it is also offered as part of hospital care. Hospice services are interdisciplinary, provided by physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and health aides. Hospices have on-call staff to assess and treat complications, avoiding emergency hospital visits.9 And hospice includes up to 5 days respite care for family caregivers, although with a 5% copay.9 Most hospice entities run inpatient facilities for care that cannot be effectively provided at home.

Hospice care has limitations—many set by insurance. Medicare, for example, stipulates that a primary care or hospice physician must certify the patient has a reasonable prognosis of 6 months or less and is expected to have a declining course.27 Patients who survive longer than 6 months are recertified by the same criteria every 60 days.27

Hospice patients forgo treatments aimed at curing their terminal diagnosis.28 Some hospice entities allow noncurative therapies while others do not. Hospice covers prescription medications for symptom control only, although patients can receive care unrelated to the terminal diagnosis under regular benefits.28 Hospice care practices differ from standard care in ways that may surprise patients and families (TABLE 227,28). Patients can disenroll and re-enroll in hospice as they wish.28

Symptom control in advanced cancer

General symptoms

Pain affects 64% of patients with advanced cancer.29 Evidence shows that cancer pain is often undertreated, with a recent systematic review reporting undertreated pain in 32% of patients.30 State and national chronic opioid guidelines do not restrict use for cancer pain.31 Opioids are effective in 75% of cancer patients over 1 month, but there is no evidence of benefit after this period.23 In fact, increasing evidence demonstrates that pain is likely negatively responsive to opioids over longer periods.32 Opioid adverse effects can worsen other cancer symptoms, including depression, anxiety, fatigue, constipation, hypogonadism, and cognitive dysfunction.32 Delaying opioid therapy to end of life can limit adverse effects and may preserve pain-control efficacy for the dying process.

Continue to: Most cancer pain...

Most cancer pain is partially neuropathic, so anticonvulsant and antidepressant medications can help.33 Gabapentin, pregabalin, and duloxetine are recommended based on evidence not restricted to cancer.34 Cannabinoids have been evaluated in 2 trials of cancer pain with 440 patients and showed a borderline significant reduction of pain.35

Palliative radiation therapy can sometimes reduce pain. Bone metastases pain has been studied the most, and the literature suggests that palliative radiation provides improvement for 60% of patients and complete relief to 25% of patients.36 Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for primary or metastatic lung masses reduces pain by more than 70% while improving dyspnea, hemoptysis, and cough in a majority of patients.36

Other uses of palliative radiation have varied evidence. Palliative chemotherapy has less evidence of benefit. In a recent multicenter cohort trial, chemotherapy in end-stage cancer reduced quality of life in patients with good functional status, without affecting quality of life when function was limited.37 Palliative chemotherapy may be beneficial if combined with corticosteroids or radiation therapy.38

Treatment in the last weeks of life centers on opioids; dose increases do not shorten survival.39 Cancer patients are 4 times as likely as noncancer patients to have severe or excruciating pain during the last 3 days of life.40 Narcotics can be titrated aggressively near end of life with less concern for hypotension, respiratory depression, or level of consciousness. Palliative sedation remains an option for uncontrolled pain.41

Anorexia is only a problem if quality of life is affected. Cachexia is caused by increases in cytokines more than reduced calorie intake.42 Reversible causes of reduced eating may be found, including candidiasis, dental problems, depression, or constipation. Megestrol acetate improves weight (number needed to treat = 12), although it significantly increases mortality (number needed to harm = 23), making its use controversial.43 Limited study of cannabinoids has not shown effectiveness in treating anorexia.35

Continue to: Constipation...

Constipation in advanced cancer is often related to opioid therapy, although bowel obstruction must be considered. Opioid-induced constipation affects 40% to 90% of patients on long-term treatment,44 and 5 days of opioid treatment nearly doubles gastrointestinal transit time.45 Opioid-induced constipation can be treated by adding a stimulating laxative followed by a peripheral acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist, such as subcutaneous methylnaltrexone or oral naloxegol.46 These medications are contraindicated if ileus or bowel obstruction is suspected.46

Nausea and vomiting are common in advanced cancer and have numerous causes. Approximately half of reversible causes are medication adverse effects from either chemotherapy or pain medication.47 Opioid rotation may improve symptoms.47 A suspected bowel obstruction should be evaluated by specialists; surgery, palliative chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or stenting may be required. Oncologists can best manage adverse effects of chemotherapy. For nausea and vomiting unrelated to chemotherapy, consider treating constipation and pain. Medication can also be helpful; a systemic review suggests metoclopramide works best, with some evidence supporting other dopaminergic agonists, including haloperidol.47

Fatigue. Both methylphenidate and modafinil have been studied to treat cancer-related fatigue.48 A majority of patients treated with methylphenidate reported less cancer-related fatigue at 4 weeks and wished to continue treatment.49 Modafinil demonstrated minimal improvement in fatigue.50 Sleep disorders, often due to anxiety or sleep apnea, may be a correctable cause.

Later symptoms

Delirium occurs in up to 90% of cancer patients near the end of life, and can signal death.51 Up to half of the delirium seen in palliative care is reversible.51 Reversible causes include uncontrolled pain, medication adverse effects, and urinary and fecal retention (TABLE 348,51). Addressing these factors reduces delirium, based on studies in postoperative patients.52 Consider opioid rotation if neurotoxicity is suspected.51

Delirium can be accompanied by agitation or decreased responsiveness.53 Agitated delirium commonly presents with moaning, facial grimacing, and purposeless repetitive movements, such as plucking bedsheets or removing clothes.51 Delirious patients without agitation have reported, following recovery, distress similar to that experienced by agitated patients.54 Caregivers are most likely to recognize delirium and often become upset. Educating family members about the frequency of delirium can lessen this distress.54

Continue to: Delirium can be treated with...

Delirium can be treated with antipsychotics; haloperidol has been most frequently studied.54 Antipsychotics are effective at reducing agitation but not at restoring cognition.55 Case reports suggest that use of atypical antipsychotics can be beneficial if adverse effects limit haloperidol dosing.56 Agitated delirium is the most frequent indication for palliative sedation.57

Dyspnea. In the last weeks, days, or hours of life, dyspnea is common and often distressing. Dyspnea appears to be multifactorial, worsened by poor control of secretions, airway hyperactivity, and lung pathologies.58 Intravenous hydration may unintentionally exacerbate dyspnea. Hospice providers generally discourage intravenous hydration because relative dehydration reduces terminal respiratory secretions (“death rattle”) and increases patient comfort.59

Some simple nonpharmacologic interventions have benefit. Oxygen is commonly employed, although multiple studies show no benefit over room air.59 Directing a handheld fan at the face does reduce dyspnea, likely by activation of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve.60

Opioids effectively treat dyspnea near the end of life with oral and parenteral dosing, but the evidence does not support nebulized opioids.61 Opioid doses required to treat dyspnea are less than those for pain and do not cause significant respiratory depression.62 If a patient taking opioids experiences dyspnea, a 25% dose increase is recommended.63

Anticholinergic medications can improve excessive airway secretions associated with dyspnea. Glycopyrrolate causes less delirium because it does not cross the blood-brain barrier, while scopolamine patches have reduced anticholinergic adverse effects, but effects are delayed until 12 hours after patch placement.64 Atropine eye drops given sublingually were effective in a small study.65

Continue to: Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation can manage intractable symptoms near the end of life. A recent systematic review suggests that palliative sedation does not shorten life.57 Sedation is most often initiated by gradual increases in medication doses.57 Midazolam is most often employed, but antipsychotics are also used.57

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, MD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4501 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; michael.arnold@usuhs.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Kristian Sanchack, MD, and James Higgins, DO, assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

As a family physician (FP), you are well positioned to optimize the quality of life of advanced cancer patients as they decline and approach death. You can help them understand their evolving prognosis so that treatment goals can be adjusted, and you can ensure that hospice is implemented early to improve the end-of-life experience. This practical review will help you to provide the best care possible for these patients.

Family physicians can fill a care gap

The term cancer survivor describes a patient who has completed initial cancer treatment. Within this population, many have declining health and ultimately succumb to their disease. There were 16.9 million cancer survivors in the United States as of January 1, 2019,1 with 53% likely to experience significant symptoms and disability.2 More than 600,000 American cancer survivors will die in 2019.3

In 2011, the Commission on Cancer mandated available outpatient palliative care services at certified cancer centers.4 Unfortunately, current palliative care resources fall far short of expected needs. A 2010 estimate of required hospice and palliative care physicians demonstrated a staffing gap of more than 50% among those providing outpatient services.5 The shortage continues,6 and many cancer patients will look to their FP for supportive care.

FPs, in addition to easing symptoms and adverse effects of medication, can educate patients and families about their disease and prognosis. By providing longitudinal care, FPs can identify critical health declines that oncologists, patients, and families often overlook. FPs can also readily appreciate decline, guide patients toward their care goals, and facilitate comfort care—including at the end of life.

Early outpatient palliative care improves quality of life and patient satisfaction. It also may improve survival time and ward off depression.7,8 Some patients and providers resist palliative care due to a misconception that it requires abandoning treatment.9 Actually, palliative care can be given in concert with all active treatments. Many experts recommend a name change from “palliative care” to “supportive care” to dispel this misconception.10

Estimate prognosis using the “surprise question”

Several algorithms are available—using between 2 and 13 patient parameters—to estimate advanced cancer survival. Most of these algorithms are designed to identify the last months or weeks of life, but their utility to predict death within these periods is limited.11

The “surprise question” may be the most valuable prognostic test for primary care. In this test, the physician asks him- or herself: Would I be surprised if this patient died in 1 year? Researchers found that when primary care physicians answered No, their patient was 4 times more likely to die within the year than when they answered Yes.12 This test has a positive predictive value of 20% and a negative predictive value of 95%, making it valuable in distinguishing patients with longer life expectancy.12 Although it overidentifies at-risk patients, the "surprise question" is a simple and sensitive tool for defining prognosis.

Continue to: Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

Priorities for patients likely to live more than a year

For patients who likely have more than a year to live, the focus is on symptom management and preparation for future decline. Initiate and facilitate discussions about end-of-life topics. Cancer survivors are often open to discussions on these topics, which include advanced directives, home health aides, and hospice.13 Patients can set specific goals for their remaining time, such as engaging in travel, personal projects, or special events. Cancer patients have better end-of-life experiences and families have improved mental health after these discussions.14 Although cancer patients are more likely than other terminal patients to have end-of-life discussions, fewer than 40% ever do.15

Address distressing symptoms with a focus on maintaining function. More than 50% of advanced cancer patients experience fatigue, weakness, pain, weight loss, and anorexia,16 and up to 60% experience psychological distress.17 Deprescribing most preventive medications is recommended with transition to symptomatic treatment.18

Priorities for patients with less than a year to live

For patients who may have less than a year to live, focus shifts to their wishes for the time remaining and priorities for the dying process. Most patients start out with prognostic views more optimistic than those of their physicians, but this gap narrows after end-of-life discussions.19,20 Patients with incurable cancer are less likely to choose aggressive therapy if they believe their 6-month survival probability is less than 90%.21 Honest conversations, with best- and worst-case scenarios, are important to patients and families, and should occur while the patient is well enough to participate and set goals.22

In the last months of life, opioids become the primary treatment for pain and air hunger. As function declines, concerns about such adverse effects as falls and confusion decrease. Opioids have been shown to be most effective over the course of 4 weeks, and avoiding their use in earlier stages may increase their efficacy at the end of life.23

Hospice benefit—more comfort, with limitations

Hospice care consists of services administered by nonprofit and for-profit entities covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and many private insurers.24 Hospice strives to allow patients to approach death in comfort, meeting their goal of a “good death.” A recent literature review identified 4 aspects of a good death that terminally ill patients and their families considered most important: control of the dying process, relief of pain, spirituality, and emotional well-being (TABLE 1).25

Continue to: Hospice use is increasing...

Hospice use is increasing, yet many enroll too late to fully benefit. While cancer patients alone are not currently tracked, the use of hospice by Medicare beneficiaries increased from 44% in 2012 to 48% in 2019.24 In 2017, the median hospice stay was 19 days.24 Unfortunately, though, just 28% of hospice-eligible patients enrolled in hospice in their last week of life.24 Without hospice, patients often receive excessive care near death. More than 6% receive aggressive chemotherapy in their last 2 weeks of life, and nearly 10% receive a life-prolonging procedure in their last month.26

Hospice care replaces standard hospital care, although patients can elect to be followed by their primary care physician.9 Most hospice services are provided as needed or continuously at the patient’s home, including assisted living facilities. And it is also offered as part of hospital care. Hospice services are interdisciplinary, provided by physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and health aides. Hospices have on-call staff to assess and treat complications, avoiding emergency hospital visits.9 And hospice includes up to 5 days respite care for family caregivers, although with a 5% copay.9 Most hospice entities run inpatient facilities for care that cannot be effectively provided at home.

Hospice care has limitations—many set by insurance. Medicare, for example, stipulates that a primary care or hospice physician must certify the patient has a reasonable prognosis of 6 months or less and is expected to have a declining course.27 Patients who survive longer than 6 months are recertified by the same criteria every 60 days.27

Hospice patients forgo treatments aimed at curing their terminal diagnosis.28 Some hospice entities allow noncurative therapies while others do not. Hospice covers prescription medications for symptom control only, although patients can receive care unrelated to the terminal diagnosis under regular benefits.28 Hospice care practices differ from standard care in ways that may surprise patients and families (TABLE 227,28). Patients can disenroll and re-enroll in hospice as they wish.28

Symptom control in advanced cancer

General symptoms

Pain affects 64% of patients with advanced cancer.29 Evidence shows that cancer pain is often undertreated, with a recent systematic review reporting undertreated pain in 32% of patients.30 State and national chronic opioid guidelines do not restrict use for cancer pain.31 Opioids are effective in 75% of cancer patients over 1 month, but there is no evidence of benefit after this period.23 In fact, increasing evidence demonstrates that pain is likely negatively responsive to opioids over longer periods.32 Opioid adverse effects can worsen other cancer symptoms, including depression, anxiety, fatigue, constipation, hypogonadism, and cognitive dysfunction.32 Delaying opioid therapy to end of life can limit adverse effects and may preserve pain-control efficacy for the dying process.

Continue to: Most cancer pain...

Most cancer pain is partially neuropathic, so anticonvulsant and antidepressant medications can help.33 Gabapentin, pregabalin, and duloxetine are recommended based on evidence not restricted to cancer.34 Cannabinoids have been evaluated in 2 trials of cancer pain with 440 patients and showed a borderline significant reduction of pain.35

Palliative radiation therapy can sometimes reduce pain. Bone metastases pain has been studied the most, and the literature suggests that palliative radiation provides improvement for 60% of patients and complete relief to 25% of patients.36 Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for primary or metastatic lung masses reduces pain by more than 70% while improving dyspnea, hemoptysis, and cough in a majority of patients.36

Other uses of palliative radiation have varied evidence. Palliative chemotherapy has less evidence of benefit. In a recent multicenter cohort trial, chemotherapy in end-stage cancer reduced quality of life in patients with good functional status, without affecting quality of life when function was limited.37 Palliative chemotherapy may be beneficial if combined with corticosteroids or radiation therapy.38

Treatment in the last weeks of life centers on opioids; dose increases do not shorten survival.39 Cancer patients are 4 times as likely as noncancer patients to have severe or excruciating pain during the last 3 days of life.40 Narcotics can be titrated aggressively near end of life with less concern for hypotension, respiratory depression, or level of consciousness. Palliative sedation remains an option for uncontrolled pain.41

Anorexia is only a problem if quality of life is affected. Cachexia is caused by increases in cytokines more than reduced calorie intake.42 Reversible causes of reduced eating may be found, including candidiasis, dental problems, depression, or constipation. Megestrol acetate improves weight (number needed to treat = 12), although it significantly increases mortality (number needed to harm = 23), making its use controversial.43 Limited study of cannabinoids has not shown effectiveness in treating anorexia.35

Continue to: Constipation...

Constipation in advanced cancer is often related to opioid therapy, although bowel obstruction must be considered. Opioid-induced constipation affects 40% to 90% of patients on long-term treatment,44 and 5 days of opioid treatment nearly doubles gastrointestinal transit time.45 Opioid-induced constipation can be treated by adding a stimulating laxative followed by a peripheral acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist, such as subcutaneous methylnaltrexone or oral naloxegol.46 These medications are contraindicated if ileus or bowel obstruction is suspected.46

Nausea and vomiting are common in advanced cancer and have numerous causes. Approximately half of reversible causes are medication adverse effects from either chemotherapy or pain medication.47 Opioid rotation may improve symptoms.47 A suspected bowel obstruction should be evaluated by specialists; surgery, palliative chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or stenting may be required. Oncologists can best manage adverse effects of chemotherapy. For nausea and vomiting unrelated to chemotherapy, consider treating constipation and pain. Medication can also be helpful; a systemic review suggests metoclopramide works best, with some evidence supporting other dopaminergic agonists, including haloperidol.47

Fatigue. Both methylphenidate and modafinil have been studied to treat cancer-related fatigue.48 A majority of patients treated with methylphenidate reported less cancer-related fatigue at 4 weeks and wished to continue treatment.49 Modafinil demonstrated minimal improvement in fatigue.50 Sleep disorders, often due to anxiety or sleep apnea, may be a correctable cause.

Later symptoms

Delirium occurs in up to 90% of cancer patients near the end of life, and can signal death.51 Up to half of the delirium seen in palliative care is reversible.51 Reversible causes include uncontrolled pain, medication adverse effects, and urinary and fecal retention (TABLE 348,51). Addressing these factors reduces delirium, based on studies in postoperative patients.52 Consider opioid rotation if neurotoxicity is suspected.51

Delirium can be accompanied by agitation or decreased responsiveness.53 Agitated delirium commonly presents with moaning, facial grimacing, and purposeless repetitive movements, such as plucking bedsheets or removing clothes.51 Delirious patients without agitation have reported, following recovery, distress similar to that experienced by agitated patients.54 Caregivers are most likely to recognize delirium and often become upset. Educating family members about the frequency of delirium can lessen this distress.54

Continue to: Delirium can be treated with...

Delirium can be treated with antipsychotics; haloperidol has been most frequently studied.54 Antipsychotics are effective at reducing agitation but not at restoring cognition.55 Case reports suggest that use of atypical antipsychotics can be beneficial if adverse effects limit haloperidol dosing.56 Agitated delirium is the most frequent indication for palliative sedation.57

Dyspnea. In the last weeks, days, or hours of life, dyspnea is common and often distressing. Dyspnea appears to be multifactorial, worsened by poor control of secretions, airway hyperactivity, and lung pathologies.58 Intravenous hydration may unintentionally exacerbate dyspnea. Hospice providers generally discourage intravenous hydration because relative dehydration reduces terminal respiratory secretions (“death rattle”) and increases patient comfort.59

Some simple nonpharmacologic interventions have benefit. Oxygen is commonly employed, although multiple studies show no benefit over room air.59 Directing a handheld fan at the face does reduce dyspnea, likely by activation of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve.60

Opioids effectively treat dyspnea near the end of life with oral and parenteral dosing, but the evidence does not support nebulized opioids.61 Opioid doses required to treat dyspnea are less than those for pain and do not cause significant respiratory depression.62 If a patient taking opioids experiences dyspnea, a 25% dose increase is recommended.63

Anticholinergic medications can improve excessive airway secretions associated with dyspnea. Glycopyrrolate causes less delirium because it does not cross the blood-brain barrier, while scopolamine patches have reduced anticholinergic adverse effects, but effects are delayed until 12 hours after patch placement.64 Atropine eye drops given sublingually were effective in a small study.65

Continue to: Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation

Palliative sedation can manage intractable symptoms near the end of life. A recent systematic review suggests that palliative sedation does not shorten life.57 Sedation is most often initiated by gradual increases in medication doses.57 Midazolam is most often employed, but antipsychotics are also used.57

CORRESPONDENCE

CDR Michael J. Arnold, MD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4501 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; michael.arnold@usuhs.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Kristian Sanchack, MD, and James Higgins, DO, assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures-2019-2021.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2019.

2. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 2. 2019. Palliative Care. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. (Must register an account for access.) Accessed September 4, 2019.

4. American Cancer Society. New CoC accreditation standards gain strong support. www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2011/coc-standards0811. Accessed September 11, 2019.

5. Lupu D; American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899-911.

6. Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1216-1223.

7. Rabow MW, Dahlin C, Calton B, et al. New frontiers in outpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:465-474.

8. Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017:CD01129.

9. Buss MK, Rock LK, McCarthy EP. Understanding palliative care and hospice: a review for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:280-286.

10. Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:372-379.

11. Simmons CPL, McMillan DC, McWilliams K, et al. Prognostic tools in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:962-970.

12. Lakin JR, Robinson MG, Bernacki RE, et al. Estimating 1-year mortality for high-risk primary care patients using the “surprise” question. JAMA Int Med. 2016;176:1863-1865.

13. Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MH, et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psychoonchology. 2015;24:287-293.

14. Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, et al. Effects of end-of-life discussions on the mental health of bereaved family members and quality of patient death and care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:17-26.

15. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

16. Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94-104.

17. Gao W, Bennett MI, Stark D, et al. Psychological distress in cancer from survivorship to end of life: prevalence, associated factors and clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2036-2044.

18. Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:121-124.

19. Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1421-1426.

20. Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, et al. Discussions of life expectancy and changes in illness understanding in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2398-2403.

21. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709-1714.

22. Myers J. Improving the quality of end-of-life discussions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:72-76.

23. Corli O, Floriani I, Roberto A, et al. Are strong opioids equally effective and safe in the treatment of chronic cancer pain? A multicenter randomized phase IV ‘real life’ trial on the variability of response to opioids. Ann Oncolog. 2016;27:1107-1115.

24. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures. 2018. www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2019.

25. Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, et al. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:261-271.

26. Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:786-796.

27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefit Facts. www.cgsmedicare.com/hhh/education/materials/pdf/Medicare_Hospice_Benefit_Facts.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefits. www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

29. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437-1449.

30. Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4149-4154.

31. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

32. Davis MP, Mehta Z. Opioids and chronic pain: where is the balance? Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18:71.

33. Leppert W, Zajaczkowska R, Wordliczek J, et al. Pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of pain in most common locations in cancer patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;67:787-799.

34. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:162-173.

35. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

36. Jones JA, Lutz ST, Chow E. et al. Palliative radiotherapy at the end of life: a critical review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:296-310.

37. Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:778-784.

38. Kongsgaard U, Kaasa S, Dale O, et al. Palliative treatment of cancer-related pain. 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464794/. Accessed September 24, 2019.

39. Sathornviriyapong A, Nagaviroj K, Anothaisintawee T. The association between different opioid doses and the survival of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:95.

40. Steindal SA, Bredal IS. Sørbye LW, et al. Pain control at the end of life: a comparative study of hospitalized cancer and noncancer patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:771-779.

41. Maltoni M, Setola E. Palliative sedation in patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:433-441.

42. Cooper C, Burden ST, Cheng H, et al. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:99-111.

43. Ruiz Garcia V, LÓpez-Briz E, Carbonell Sanchis R, et al. Megesterol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;28:CD004310.

44. Chey WD, Webster L, Sostek M, et al. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2387-2396.

45. Poulsen JL, Nilsson M, Brock C, et al. The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:282-291.

46. Pergolizzi JV, Raffa RB, Pappagallo M, et al. Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists as treatment options for constipation in noncancer pain patients on chronic opioid therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:107-119.

47. Walsh D, Davis M, Ripamonti C, et al. 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:333-340.

48. Mücke M, Mochamat, Cuhls H, et al. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(5):CD006788.

49. Escalante CP, Meyers C, Reuben JM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, 2-period, placebo-controlled crossover trial of a sustained-release methylphenidate in the treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. Cancer J. 2014;20:8-14.

50. Hovey E, de Souza P, Marx G, et al. Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of modafinil for fatigue in patients treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1233-1242.

51. Hosker CM, Bennett MI. Delirium and agitation at the end of life. BMJ. 2016;353:i3085.

52. Mercantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:516-522.

53. Casarett DJ, Inouye SK. Diagnosis and management of delirium near the end of life. Ann Int Med. 2001;135:32-40.

54. Breitbart W, Alici Y. Agitation and delirium at the end of life: “We couldn’t manage him." JAMA. 2008;300:2898-2910.

55. Candy B, Jackson KC, Jones L, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD004770.

56. Bascom PB, Bordley JL, Lawton AJ. High-dose neuroleptics and neuroleptic rotation for agitated delirium near the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31:808-811.

57. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, et al. Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1378-1383.

58. Albert RH. End-of-life care: managing common symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:356-361.

59. Arenella C. Artificial nutrition and hydration at the end of life: beneficial or harmful? https://americanhospice.org/caregiving/artificial-nutrition-and-hydration-at-the-end-of-life-beneficial-or-harmful/ Accessed September 11, 2019.

60. Booth S, Moffat C, Burkin J, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for breathlessness. Curr Opinion Support Pall Care. 2011;5:77-86.

61. Barnes H, McDonald J, Smallwood N, et al. Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(3)CD011008.

62. Lim RB. End-of-life care in patients with advanced lung cancer. Ther Adv Resp Dis. 2016;10:455-467.

63. Kreher M. Symptom control at the end of life. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100:1111-1122.

64. Baralatei FT, Ackerman RJ. Care of patients at the end of life: management of nonpain symptoms. FP Essent. 2016;447:18-24.

65. Protus BM, Grauer PA, Kimbrel JM. Evaluation of atropine 1% ophthalmic solution administered sublingual for the management of terminal respiratory secretions. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30:388-392.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019-2021. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures-2019-2021.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2019.

2. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 2. 2019. Palliative Care. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. (Must register an account for access.) Accessed September 4, 2019.

4. American Cancer Society. New CoC accreditation standards gain strong support. www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2011/coc-standards0811. Accessed September 11, 2019.

5. Lupu D; American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899-911.

6. Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1216-1223.

7. Rabow MW, Dahlin C, Calton B, et al. New frontiers in outpatient palliative care for patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:465-474.

8. Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017:CD01129.

9. Buss MK, Rock LK, McCarthy EP. Understanding palliative care and hospice: a review for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:280-286.

10. Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:372-379.

11. Simmons CPL, McMillan DC, McWilliams K, et al. Prognostic tools in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:962-970.

12. Lakin JR, Robinson MG, Bernacki RE, et al. Estimating 1-year mortality for high-risk primary care patients using the “surprise” question. JAMA Int Med. 2016;176:1863-1865.

13. Walczak A, Henselmans I, Tattersall MH, et al. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psychoonchology. 2015;24:287-293.

14. Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, et al. Effects of end-of-life discussions on the mental health of bereaved family members and quality of patient death and care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:17-26.

15. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

16. Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94-104.

17. Gao W, Bennett MI, Stark D, et al. Psychological distress in cancer from survivorship to end of life: prevalence, associated factors and clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2036-2044.

18. Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, et al. Deciding when to stop: towards evidence-based deprescribing of drugs in older populations. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:121-124.

19. Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1421-1426.

20. Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, et al. Discussions of life expectancy and changes in illness understanding in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2398-2403.

21. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709-1714.

22. Myers J. Improving the quality of end-of-life discussions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:72-76.

23. Corli O, Floriani I, Roberto A, et al. Are strong opioids equally effective and safe in the treatment of chronic cancer pain? A multicenter randomized phase IV ‘real life’ trial on the variability of response to opioids. Ann Oncolog. 2016;27:1107-1115.

24. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures. 2018. www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2019.

25. Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, et al. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:261-271.

26. Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:786-796.

27. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefit Facts. www.cgsmedicare.com/hhh/education/materials/pdf/Medicare_Hospice_Benefit_Facts.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

28. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefits. www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2019.

29. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437-1449.

30. Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4149-4154.

31. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

32. Davis MP, Mehta Z. Opioids and chronic pain: where is the balance? Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18:71.

33. Leppert W, Zajaczkowska R, Wordliczek J, et al. Pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of pain in most common locations in cancer patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;67:787-799.

34. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:162-173.

35. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456-2473.

36. Jones JA, Lutz ST, Chow E. et al. Palliative radiotherapy at the end of life: a critical review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:296-310.

37. Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:778-784.

38. Kongsgaard U, Kaasa S, Dale O, et al. Palliative treatment of cancer-related pain. 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464794/. Accessed September 24, 2019.

39. Sathornviriyapong A, Nagaviroj K, Anothaisintawee T. The association between different opioid doses and the survival of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:95.

40. Steindal SA, Bredal IS. Sørbye LW, et al. Pain control at the end of life: a comparative study of hospitalized cancer and noncancer patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:771-779.

41. Maltoni M, Setola E. Palliative sedation in patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2015;22:433-441.

42. Cooper C, Burden ST, Cheng H, et al. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6:99-111.

43. Ruiz Garcia V, LÓpez-Briz E, Carbonell Sanchis R, et al. Megesterol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;28:CD004310.

44. Chey WD, Webster L, Sostek M, et al. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2387-2396.

45. Poulsen JL, Nilsson M, Brock C, et al. The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:282-291.