User login

To apropriately manage gout, it is important to distinguish between treatment of acute gout attacks and management of the underlying metabolic defect. While acute attacks are treated with anti-inflammatory agents, the underlying hyperuricemia must be addressed by lowering the serum urate concentration to levels that lead to prevention of acute flares, together with consideration of the contributing role of the patient’s lifestyle factors and comorbidities. This article surveys treatment options for both acute gout attacks and the underlying hyperuricemic state, focusing on considerations to guide therapy selection and optimize prospects for treatment success.

ACUTE GOUTY ARTHRITIS: ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS AND KEY ISSUES FOR THEIR USE

One of the most important considerations in selecting an anti-inflammatory medication is how the patient’s comorbidities, such as renal disease, or concurrent medications may influence the choice of agent, as outlined in Table 1.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

A number of NSAIDs are available to treat acute flares of gout.1–3 When used at a full anti-inflammatory dose, all NSAIDs appear to be equally effective.

NSAIDs must be used cautiously in patients who have any of a number of comorbid conditions, as detailed in Table 1. If a patient is otherwise healthy—without significant renal, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal disease—and has no history of aspirin allergy, NSAIDs are the treatment of choice for acute gout attacks. Use of a proton pump inhibitor can improve gastrointestinal tolerance of NSAIDs and reduce the likelihood of gastric bleeding but may not avoid other concerns. Indomethacin can cause headache or even confusion, particularly in the elderly.

Colchicine

Colchicine can be an effective alternative for acute therapy.4,5 If a patient with previously documented gout can be coached to begin colchicine at the first hint of a gout attack, a full-blown attack often can be prevented. A colchicine regimen of 0.5 or 0.6 mg 3 times daily, although not well studied, may be effective while limiting the diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting that is predictable with hourly colchicine dosing.6,7 Colchicine must be used cautiously in patients with renal or liver disease and is contraindicated in patients undergoing dialysis.8

Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are often used for polyarticular gout or in patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or colchicine.9 When they are used in diabetic patients, glycemic control must be monitored, and an increased insulin dose can be prescribed temporarily until glucose levels normalize.

Corticosteroids may also be injected directly into the joint, as this approach offers reduced risks compared with oral administration. Direct injection is especially useful in patients with attacks that involve only one or two joints.

TREATING THE UNDERLYING HYPERURICEMIA THROUGH URATE-LOWERING STRATEGIES

Terminating the acute flare manages gout symptoms but does not treat the underlying disease. Crystals often remain in the joint after flares have resolved. Addressing the underlying metabolic condition requires lowering serum urate levels, which can deplete crystals and reduce or prevent gout flares.

The goals of urate-lowering therapy are to reduce serum urate levels to less than 6 mg/dL in order to mobilize and deplete crystals with minimal toxicity.10

Role of lifestyle interventions

As discussed by Weaver earlier in this supplement, obesity and certain patterns of food and alcohol consumption can increase the risk of developing hyperuricemia and gout. In addition to weight loss, dietary changes.such as reducing intake of animal purines, high-fructose sweeteners, and alcohol, and increasing intake of vitamin C or bing cherries.may lower serum urate levels modestly (ie, by 1 or 2 mg/dL).11–15 While lifestyle interventions may be all that is needed in some patients with early mild gout, such interventions generally do not replace the need for urate-lowering drug therapy in cases of existing gout. Accordingly, this discussion focuses on medications used to treat hyperuricemia in the United States: the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol and the uricosuric agent probenecid.

Initiating urate-lowering drug therapy

Chronic therapy should be discussed with the patient early in the course of the disease. Treatment recommendations need to be individualized based on the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, and willingness to adhere to chronic treatment.

Initiation of urate-lowering therapy is appropriate to consider after the acute attack has fully resolved and the patient has been stable for 1 to 2 weeks. If a patient’s serum urate level is very high (eg, > 10 mg/dL), urate-lowering therapy may be initiated even after a single attack, as progression is more likely to occur with higher levels. Treatment should be initiated long before tophi or persistent joint damage develop. If the patient already has objective radiographic evidence of gouty changes in the joints, or if tophi or nephrolithiasis are present when the patient is first seen, urate-lowering therapy should be started.

Concurrent low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis

Abrupt decreases (or increases) in serum urate levels may precipitate gout flares. For this reason, anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be used when urate-lowering therapy is initiated, as it can quickly reduce serum urate levels. Colchicine (0.6 mg once or twice daily)8 or NSAIDs (eg, naproxen 250 mg/day) prescribed at lower than full anti-inflammatory doses may be used to prevent flares in this setting. When using long-term colchicine in a patient with renal disease, lower doses must be used and the patient should be monitored closely for reversible axonal neuromyopathy and vacuolar myopathy or rhabdomyolysis; the latter complication may be more frequent in patients taking concurrent statin or macrolide therapy. There are no controlled studies on the benefits and safety of prophylactic NSAID use in gouty patients with comorbidities.

Borstad et al documented in a placebo-controlled study that colchicine prophylaxis at the time of allopurinol initiation reduces flares but does not completely abolish them.16 From 0 to 3 months after therapy initiation, the mean number of flares was 0.57 in patients who received colchicine versus 1.91 in patients who received placebo (P = .022); from 3 to 6 months after initiation, the mean number of flares was 0 versus 1.05 in the respective patient groups (P = .033).16

Depending on the body’s urate load, it may take many months to deplete crystals. There is evidence that prophylaxis should be used for at least 3 to 6 months to reduce the risk of mobilization flares.16 Patients should be warned during this time that gout flares may still occur and should be treated promptly. Prophylaxis should continue longer in patients with tophi, often until the tophi have resolved.

Allopurinol

The rare but potentially fatal hypersensitivity syndrome is a concern with allopurinol. If a rash develops in a patient taking allopurinol, the drug should be discontinued, as rash can be a precursor of severe systemic hypersensitivity.

Renal function must be considered in allopurinol dosing, and treatment should always be initiated at lower doses in patients with renal disease.18 However, recent reports indicate that allopurinol doses can be gradually and safely increased to an effective level that achieves a serum urate concentration of less than 6 mg/dL even in patients with reduced kidney function.19,20

Uricosurics

The uricosuric agent probenecid works by increasing the urinary excretion of urate.10 Probenecid is commonly dosed at 500 mg twice daily, with a maximum daily dose of 2 g, in an attempt to reach the target serum urate level. Probenecid is unlikely to be effective if the patient’s serum creatinine is greater than 2 mg/dL.21

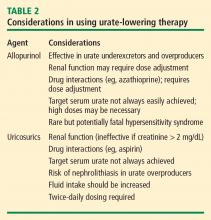

When a uricosuric agent is used, a 24-hour urine urate measurement must be taken to identify and exclude urate overproducers (patients with more than 800 to 1,000 mg of uric acid in a good 24-hour collection), as such patients are at risk for uric acid kidney stones. Additionally, aspirin interferes with probenecid’s effect on the renal tubules. The ideal candidate for uricosuric therapy has good kidney function, is not a urate overproducer, and is willing to drink 8 glasses of water a day to minimize the risk of kidney stones (Table 2).

Evidence supporting urate targets and continuous maintenance of urate reductions

If a serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL is achieved and maintained, gout flares will be reduced and crystals can be depleted from inside the joint.22–25 Additionally, the size of tophi can be reduced and their recurrence prevented.26–28 Serum urate levels below 4 mg/dL can result in more rapid dissolution of tophi.26

Patient commitment and education are essential

No treatment plan will succeed without the commitment of the patient, so discussion to determine the patient’s willingness to commit to lifetime therapy is warranted. A number of surveys have shown that the rate of continued use of allopurinol after it is initially prescribed is less than 50%.17 If the physician or nurse monitors adherence, however, treatment is more likely to be successful.30

Patients need more education about gout, as education may improve adherence and treatment success. Patient education material is available from the Arthritis Foundation (www.arthritis.org/disease-center.php) and the Gout & Uric Acid Education Society (www.gouteducation.org).

CONCLUSION

A comprehensive treatment strategy is critical to ensure ideal gout therapy. Acute flares should be addressed as rapidly as possible with an anti-inflammatory agent selected on the basis of the patient’s comorbidities and other medications. Most patients require chronic urate-lowering therapy to deplete crystals from joints and prevent flares. Initiation of urate-lowering therapy should be considered early in the disease course, following resolution of the acute attack. Low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be initiated when any urate-lowering therapy is started. Regular monitoring of serum urate will ensure effective dosing to achieve a target serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL. Once urate deposits are depleted, acute flares should cease.

- Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988; 15:1422–1426.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002; 324:1488–1492.

- Willburger RE, Mysler E, Derbot J, et al. Lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily is comparable to indomethacin 50 mg three times daily for the treatment of acute flares of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007; 46:1126–1132.

- Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon T, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987; 17:301–304.

- Schlesinger N, Moore DF, Sun JD, Schumacher HR Jr. A survey of current evaluation and treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2050–2052.

- Rozenberg S, Lang T, Laatar A, Koeger AC, Orcel P, Bourgerois P. Diversity of opinions on the management of gout in France. A survey of 750 rheumatologists. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1996; 63:255–261.

- Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 18:CD006190.

- Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA 2003; 289:2857–2860.

- Alloway JA, Moriarity MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:111–113.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Chen LX. Newer therapeutic approaches: gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006; 32:235–244, xii.

- Choi HK. Diet, alcohol, and gout: how do we advise patients given recent developments? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2005; 7:220–226.

- Johnson MW, Mitch WE. The risks of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and the use of uricosuric diuretics. Drugs 1981; 21:220–225.

- Berger L, Yü TF. Renal function in gout. IV. An analysis of 524 gouty subjects including long-term follow-up studies. Am J Med 1975; 59:605–613.

- Stein HB, Hasan A, Fox IH. Ascorbic acid-induced uricosuria. A consequence of megavitamin therapy. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:385–388.

- Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59:109–116.

- Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, Scroggie DA, Harris MD, Alloway JA. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31:2429–2432.

- Sarawate CA, Patel PA, Schumacher HR, Yang W, Brewer KK, Bakst AW. Serum urate levels and gout flares: analysis from managed care data. J Clin Rheumatol 2006; 12:61–65.

- Hande KR, Noone RM, Stone WJ. Severe allopurinol toxicity. Description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Med 1984; 76:47–56.

- Vázquez-Mellado J, Morales EM, Pacheco-Tena C, Burgos-Vargas R. Relation between adverse events associated with allopurinol and renal function in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:981–983.

- Dalbeth N, Kumar S, Stamp L, Gow P. Dose adjustment of allopurinol according to creatinine clearance does not provide adequate control of hyperuricemia in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1646–1650.

- Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:445–451.

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann, RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2450–2461.

- Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, et al. Treatment of chronic gout. Can we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout? J Rheumatol 2001; 28:577–580.

- Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with anti-hyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51:321–325.

- Pascual E, Sivera F. Time required for disappearance of urate crystals from synovial fluid after successful hypouricaemic treatment relates to the duration of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:1056–1058.

- Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan JI, Herrero-Beites AM, Ruibal A. Effect of urate-lowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47:356–360

- McCarthy GM, Barthelemy CR, Veum JA, Wortmann RL. Influence of antihyperuricemic therapy on the clinical and radiographic progression of gout. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34:1489–1494.

- van Lieshout-Zuidema MF, Breedveld FC. Withdrawal of long-term antihyperuricemic therapy in tophaceous gout. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:1383–1385.

- Bull PW, Scott JT. Intermittent control of hyperuricemia in the treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 1989; 16:1246–1248.

- Murphy-Bielicki, Schumacher HR. How does patient education affect gout? Clin Rheumatol Pract 1984; 2:77–80.

To apropriately manage gout, it is important to distinguish between treatment of acute gout attacks and management of the underlying metabolic defect. While acute attacks are treated with anti-inflammatory agents, the underlying hyperuricemia must be addressed by lowering the serum urate concentration to levels that lead to prevention of acute flares, together with consideration of the contributing role of the patient’s lifestyle factors and comorbidities. This article surveys treatment options for both acute gout attacks and the underlying hyperuricemic state, focusing on considerations to guide therapy selection and optimize prospects for treatment success.

ACUTE GOUTY ARTHRITIS: ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS AND KEY ISSUES FOR THEIR USE

One of the most important considerations in selecting an anti-inflammatory medication is how the patient’s comorbidities, such as renal disease, or concurrent medications may influence the choice of agent, as outlined in Table 1.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

A number of NSAIDs are available to treat acute flares of gout.1–3 When used at a full anti-inflammatory dose, all NSAIDs appear to be equally effective.

NSAIDs must be used cautiously in patients who have any of a number of comorbid conditions, as detailed in Table 1. If a patient is otherwise healthy—without significant renal, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal disease—and has no history of aspirin allergy, NSAIDs are the treatment of choice for acute gout attacks. Use of a proton pump inhibitor can improve gastrointestinal tolerance of NSAIDs and reduce the likelihood of gastric bleeding but may not avoid other concerns. Indomethacin can cause headache or even confusion, particularly in the elderly.

Colchicine

Colchicine can be an effective alternative for acute therapy.4,5 If a patient with previously documented gout can be coached to begin colchicine at the first hint of a gout attack, a full-blown attack often can be prevented. A colchicine regimen of 0.5 or 0.6 mg 3 times daily, although not well studied, may be effective while limiting the diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting that is predictable with hourly colchicine dosing.6,7 Colchicine must be used cautiously in patients with renal or liver disease and is contraindicated in patients undergoing dialysis.8

Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are often used for polyarticular gout or in patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or colchicine.9 When they are used in diabetic patients, glycemic control must be monitored, and an increased insulin dose can be prescribed temporarily until glucose levels normalize.

Corticosteroids may also be injected directly into the joint, as this approach offers reduced risks compared with oral administration. Direct injection is especially useful in patients with attacks that involve only one or two joints.

TREATING THE UNDERLYING HYPERURICEMIA THROUGH URATE-LOWERING STRATEGIES

Terminating the acute flare manages gout symptoms but does not treat the underlying disease. Crystals often remain in the joint after flares have resolved. Addressing the underlying metabolic condition requires lowering serum urate levels, which can deplete crystals and reduce or prevent gout flares.

The goals of urate-lowering therapy are to reduce serum urate levels to less than 6 mg/dL in order to mobilize and deplete crystals with minimal toxicity.10

Role of lifestyle interventions

As discussed by Weaver earlier in this supplement, obesity and certain patterns of food and alcohol consumption can increase the risk of developing hyperuricemia and gout. In addition to weight loss, dietary changes.such as reducing intake of animal purines, high-fructose sweeteners, and alcohol, and increasing intake of vitamin C or bing cherries.may lower serum urate levels modestly (ie, by 1 or 2 mg/dL).11–15 While lifestyle interventions may be all that is needed in some patients with early mild gout, such interventions generally do not replace the need for urate-lowering drug therapy in cases of existing gout. Accordingly, this discussion focuses on medications used to treat hyperuricemia in the United States: the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol and the uricosuric agent probenecid.

Initiating urate-lowering drug therapy

Chronic therapy should be discussed with the patient early in the course of the disease. Treatment recommendations need to be individualized based on the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, and willingness to adhere to chronic treatment.

Initiation of urate-lowering therapy is appropriate to consider after the acute attack has fully resolved and the patient has been stable for 1 to 2 weeks. If a patient’s serum urate level is very high (eg, > 10 mg/dL), urate-lowering therapy may be initiated even after a single attack, as progression is more likely to occur with higher levels. Treatment should be initiated long before tophi or persistent joint damage develop. If the patient already has objective radiographic evidence of gouty changes in the joints, or if tophi or nephrolithiasis are present when the patient is first seen, urate-lowering therapy should be started.

Concurrent low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis

Abrupt decreases (or increases) in serum urate levels may precipitate gout flares. For this reason, anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be used when urate-lowering therapy is initiated, as it can quickly reduce serum urate levels. Colchicine (0.6 mg once or twice daily)8 or NSAIDs (eg, naproxen 250 mg/day) prescribed at lower than full anti-inflammatory doses may be used to prevent flares in this setting. When using long-term colchicine in a patient with renal disease, lower doses must be used and the patient should be monitored closely for reversible axonal neuromyopathy and vacuolar myopathy or rhabdomyolysis; the latter complication may be more frequent in patients taking concurrent statin or macrolide therapy. There are no controlled studies on the benefits and safety of prophylactic NSAID use in gouty patients with comorbidities.

Borstad et al documented in a placebo-controlled study that colchicine prophylaxis at the time of allopurinol initiation reduces flares but does not completely abolish them.16 From 0 to 3 months after therapy initiation, the mean number of flares was 0.57 in patients who received colchicine versus 1.91 in patients who received placebo (P = .022); from 3 to 6 months after initiation, the mean number of flares was 0 versus 1.05 in the respective patient groups (P = .033).16

Depending on the body’s urate load, it may take many months to deplete crystals. There is evidence that prophylaxis should be used for at least 3 to 6 months to reduce the risk of mobilization flares.16 Patients should be warned during this time that gout flares may still occur and should be treated promptly. Prophylaxis should continue longer in patients with tophi, often until the tophi have resolved.

Allopurinol

The rare but potentially fatal hypersensitivity syndrome is a concern with allopurinol. If a rash develops in a patient taking allopurinol, the drug should be discontinued, as rash can be a precursor of severe systemic hypersensitivity.

Renal function must be considered in allopurinol dosing, and treatment should always be initiated at lower doses in patients with renal disease.18 However, recent reports indicate that allopurinol doses can be gradually and safely increased to an effective level that achieves a serum urate concentration of less than 6 mg/dL even in patients with reduced kidney function.19,20

Uricosurics

The uricosuric agent probenecid works by increasing the urinary excretion of urate.10 Probenecid is commonly dosed at 500 mg twice daily, with a maximum daily dose of 2 g, in an attempt to reach the target serum urate level. Probenecid is unlikely to be effective if the patient’s serum creatinine is greater than 2 mg/dL.21

When a uricosuric agent is used, a 24-hour urine urate measurement must be taken to identify and exclude urate overproducers (patients with more than 800 to 1,000 mg of uric acid in a good 24-hour collection), as such patients are at risk for uric acid kidney stones. Additionally, aspirin interferes with probenecid’s effect on the renal tubules. The ideal candidate for uricosuric therapy has good kidney function, is not a urate overproducer, and is willing to drink 8 glasses of water a day to minimize the risk of kidney stones (Table 2).

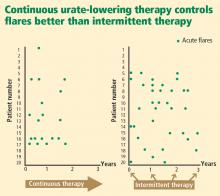

Evidence supporting urate targets and continuous maintenance of urate reductions

If a serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL is achieved and maintained, gout flares will be reduced and crystals can be depleted from inside the joint.22–25 Additionally, the size of tophi can be reduced and their recurrence prevented.26–28 Serum urate levels below 4 mg/dL can result in more rapid dissolution of tophi.26

Patient commitment and education are essential

No treatment plan will succeed without the commitment of the patient, so discussion to determine the patient’s willingness to commit to lifetime therapy is warranted. A number of surveys have shown that the rate of continued use of allopurinol after it is initially prescribed is less than 50%.17 If the physician or nurse monitors adherence, however, treatment is more likely to be successful.30

Patients need more education about gout, as education may improve adherence and treatment success. Patient education material is available from the Arthritis Foundation (www.arthritis.org/disease-center.php) and the Gout & Uric Acid Education Society (www.gouteducation.org).

CONCLUSION

A comprehensive treatment strategy is critical to ensure ideal gout therapy. Acute flares should be addressed as rapidly as possible with an anti-inflammatory agent selected on the basis of the patient’s comorbidities and other medications. Most patients require chronic urate-lowering therapy to deplete crystals from joints and prevent flares. Initiation of urate-lowering therapy should be considered early in the disease course, following resolution of the acute attack. Low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be initiated when any urate-lowering therapy is started. Regular monitoring of serum urate will ensure effective dosing to achieve a target serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL. Once urate deposits are depleted, acute flares should cease.

To apropriately manage gout, it is important to distinguish between treatment of acute gout attacks and management of the underlying metabolic defect. While acute attacks are treated with anti-inflammatory agents, the underlying hyperuricemia must be addressed by lowering the serum urate concentration to levels that lead to prevention of acute flares, together with consideration of the contributing role of the patient’s lifestyle factors and comorbidities. This article surveys treatment options for both acute gout attacks and the underlying hyperuricemic state, focusing on considerations to guide therapy selection and optimize prospects for treatment success.

ACUTE GOUTY ARTHRITIS: ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS AND KEY ISSUES FOR THEIR USE

One of the most important considerations in selecting an anti-inflammatory medication is how the patient’s comorbidities, such as renal disease, or concurrent medications may influence the choice of agent, as outlined in Table 1.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

A number of NSAIDs are available to treat acute flares of gout.1–3 When used at a full anti-inflammatory dose, all NSAIDs appear to be equally effective.

NSAIDs must be used cautiously in patients who have any of a number of comorbid conditions, as detailed in Table 1. If a patient is otherwise healthy—without significant renal, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal disease—and has no history of aspirin allergy, NSAIDs are the treatment of choice for acute gout attacks. Use of a proton pump inhibitor can improve gastrointestinal tolerance of NSAIDs and reduce the likelihood of gastric bleeding but may not avoid other concerns. Indomethacin can cause headache or even confusion, particularly in the elderly.

Colchicine

Colchicine can be an effective alternative for acute therapy.4,5 If a patient with previously documented gout can be coached to begin colchicine at the first hint of a gout attack, a full-blown attack often can be prevented. A colchicine regimen of 0.5 or 0.6 mg 3 times daily, although not well studied, may be effective while limiting the diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting that is predictable with hourly colchicine dosing.6,7 Colchicine must be used cautiously in patients with renal or liver disease and is contraindicated in patients undergoing dialysis.8

Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are often used for polyarticular gout or in patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or colchicine.9 When they are used in diabetic patients, glycemic control must be monitored, and an increased insulin dose can be prescribed temporarily until glucose levels normalize.

Corticosteroids may also be injected directly into the joint, as this approach offers reduced risks compared with oral administration. Direct injection is especially useful in patients with attacks that involve only one or two joints.

TREATING THE UNDERLYING HYPERURICEMIA THROUGH URATE-LOWERING STRATEGIES

Terminating the acute flare manages gout symptoms but does not treat the underlying disease. Crystals often remain in the joint after flares have resolved. Addressing the underlying metabolic condition requires lowering serum urate levels, which can deplete crystals and reduce or prevent gout flares.

The goals of urate-lowering therapy are to reduce serum urate levels to less than 6 mg/dL in order to mobilize and deplete crystals with minimal toxicity.10

Role of lifestyle interventions

As discussed by Weaver earlier in this supplement, obesity and certain patterns of food and alcohol consumption can increase the risk of developing hyperuricemia and gout. In addition to weight loss, dietary changes.such as reducing intake of animal purines, high-fructose sweeteners, and alcohol, and increasing intake of vitamin C or bing cherries.may lower serum urate levels modestly (ie, by 1 or 2 mg/dL).11–15 While lifestyle interventions may be all that is needed in some patients with early mild gout, such interventions generally do not replace the need for urate-lowering drug therapy in cases of existing gout. Accordingly, this discussion focuses on medications used to treat hyperuricemia in the United States: the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol and the uricosuric agent probenecid.

Initiating urate-lowering drug therapy

Chronic therapy should be discussed with the patient early in the course of the disease. Treatment recommendations need to be individualized based on the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, and willingness to adhere to chronic treatment.

Initiation of urate-lowering therapy is appropriate to consider after the acute attack has fully resolved and the patient has been stable for 1 to 2 weeks. If a patient’s serum urate level is very high (eg, > 10 mg/dL), urate-lowering therapy may be initiated even after a single attack, as progression is more likely to occur with higher levels. Treatment should be initiated long before tophi or persistent joint damage develop. If the patient already has objective radiographic evidence of gouty changes in the joints, or if tophi or nephrolithiasis are present when the patient is first seen, urate-lowering therapy should be started.

Concurrent low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis

Abrupt decreases (or increases) in serum urate levels may precipitate gout flares. For this reason, anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be used when urate-lowering therapy is initiated, as it can quickly reduce serum urate levels. Colchicine (0.6 mg once or twice daily)8 or NSAIDs (eg, naproxen 250 mg/day) prescribed at lower than full anti-inflammatory doses may be used to prevent flares in this setting. When using long-term colchicine in a patient with renal disease, lower doses must be used and the patient should be monitored closely for reversible axonal neuromyopathy and vacuolar myopathy or rhabdomyolysis; the latter complication may be more frequent in patients taking concurrent statin or macrolide therapy. There are no controlled studies on the benefits and safety of prophylactic NSAID use in gouty patients with comorbidities.

Borstad et al documented in a placebo-controlled study that colchicine prophylaxis at the time of allopurinol initiation reduces flares but does not completely abolish them.16 From 0 to 3 months after therapy initiation, the mean number of flares was 0.57 in patients who received colchicine versus 1.91 in patients who received placebo (P = .022); from 3 to 6 months after initiation, the mean number of flares was 0 versus 1.05 in the respective patient groups (P = .033).16

Depending on the body’s urate load, it may take many months to deplete crystals. There is evidence that prophylaxis should be used for at least 3 to 6 months to reduce the risk of mobilization flares.16 Patients should be warned during this time that gout flares may still occur and should be treated promptly. Prophylaxis should continue longer in patients with tophi, often until the tophi have resolved.

Allopurinol

The rare but potentially fatal hypersensitivity syndrome is a concern with allopurinol. If a rash develops in a patient taking allopurinol, the drug should be discontinued, as rash can be a precursor of severe systemic hypersensitivity.

Renal function must be considered in allopurinol dosing, and treatment should always be initiated at lower doses in patients with renal disease.18 However, recent reports indicate that allopurinol doses can be gradually and safely increased to an effective level that achieves a serum urate concentration of less than 6 mg/dL even in patients with reduced kidney function.19,20

Uricosurics

The uricosuric agent probenecid works by increasing the urinary excretion of urate.10 Probenecid is commonly dosed at 500 mg twice daily, with a maximum daily dose of 2 g, in an attempt to reach the target serum urate level. Probenecid is unlikely to be effective if the patient’s serum creatinine is greater than 2 mg/dL.21

When a uricosuric agent is used, a 24-hour urine urate measurement must be taken to identify and exclude urate overproducers (patients with more than 800 to 1,000 mg of uric acid in a good 24-hour collection), as such patients are at risk for uric acid kidney stones. Additionally, aspirin interferes with probenecid’s effect on the renal tubules. The ideal candidate for uricosuric therapy has good kidney function, is not a urate overproducer, and is willing to drink 8 glasses of water a day to minimize the risk of kidney stones (Table 2).

Evidence supporting urate targets and continuous maintenance of urate reductions

If a serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL is achieved and maintained, gout flares will be reduced and crystals can be depleted from inside the joint.22–25 Additionally, the size of tophi can be reduced and their recurrence prevented.26–28 Serum urate levels below 4 mg/dL can result in more rapid dissolution of tophi.26

Patient commitment and education are essential

No treatment plan will succeed without the commitment of the patient, so discussion to determine the patient’s willingness to commit to lifetime therapy is warranted. A number of surveys have shown that the rate of continued use of allopurinol after it is initially prescribed is less than 50%.17 If the physician or nurse monitors adherence, however, treatment is more likely to be successful.30

Patients need more education about gout, as education may improve adherence and treatment success. Patient education material is available from the Arthritis Foundation (www.arthritis.org/disease-center.php) and the Gout & Uric Acid Education Society (www.gouteducation.org).

CONCLUSION

A comprehensive treatment strategy is critical to ensure ideal gout therapy. Acute flares should be addressed as rapidly as possible with an anti-inflammatory agent selected on the basis of the patient’s comorbidities and other medications. Most patients require chronic urate-lowering therapy to deplete crystals from joints and prevent flares. Initiation of urate-lowering therapy should be considered early in the disease course, following resolution of the acute attack. Low-dose anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be initiated when any urate-lowering therapy is started. Regular monitoring of serum urate will ensure effective dosing to achieve a target serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL. Once urate deposits are depleted, acute flares should cease.

- Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988; 15:1422–1426.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002; 324:1488–1492.

- Willburger RE, Mysler E, Derbot J, et al. Lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily is comparable to indomethacin 50 mg three times daily for the treatment of acute flares of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007; 46:1126–1132.

- Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon T, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987; 17:301–304.

- Schlesinger N, Moore DF, Sun JD, Schumacher HR Jr. A survey of current evaluation and treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2050–2052.

- Rozenberg S, Lang T, Laatar A, Koeger AC, Orcel P, Bourgerois P. Diversity of opinions on the management of gout in France. A survey of 750 rheumatologists. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1996; 63:255–261.

- Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 18:CD006190.

- Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA 2003; 289:2857–2860.

- Alloway JA, Moriarity MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:111–113.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Chen LX. Newer therapeutic approaches: gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006; 32:235–244, xii.

- Choi HK. Diet, alcohol, and gout: how do we advise patients given recent developments? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2005; 7:220–226.

- Johnson MW, Mitch WE. The risks of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and the use of uricosuric diuretics. Drugs 1981; 21:220–225.

- Berger L, Yü TF. Renal function in gout. IV. An analysis of 524 gouty subjects including long-term follow-up studies. Am J Med 1975; 59:605–613.

- Stein HB, Hasan A, Fox IH. Ascorbic acid-induced uricosuria. A consequence of megavitamin therapy. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:385–388.

- Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59:109–116.

- Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, Scroggie DA, Harris MD, Alloway JA. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31:2429–2432.

- Sarawate CA, Patel PA, Schumacher HR, Yang W, Brewer KK, Bakst AW. Serum urate levels and gout flares: analysis from managed care data. J Clin Rheumatol 2006; 12:61–65.

- Hande KR, Noone RM, Stone WJ. Severe allopurinol toxicity. Description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Med 1984; 76:47–56.

- Vázquez-Mellado J, Morales EM, Pacheco-Tena C, Burgos-Vargas R. Relation between adverse events associated with allopurinol and renal function in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:981–983.

- Dalbeth N, Kumar S, Stamp L, Gow P. Dose adjustment of allopurinol according to creatinine clearance does not provide adequate control of hyperuricemia in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1646–1650.

- Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:445–451.

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann, RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2450–2461.

- Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, et al. Treatment of chronic gout. Can we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout? J Rheumatol 2001; 28:577–580.

- Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with anti-hyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51:321–325.

- Pascual E, Sivera F. Time required for disappearance of urate crystals from synovial fluid after successful hypouricaemic treatment relates to the duration of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:1056–1058.

- Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan JI, Herrero-Beites AM, Ruibal A. Effect of urate-lowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47:356–360

- McCarthy GM, Barthelemy CR, Veum JA, Wortmann RL. Influence of antihyperuricemic therapy on the clinical and radiographic progression of gout. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34:1489–1494.

- van Lieshout-Zuidema MF, Breedveld FC. Withdrawal of long-term antihyperuricemic therapy in tophaceous gout. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:1383–1385.

- Bull PW, Scott JT. Intermittent control of hyperuricemia in the treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 1989; 16:1246–1248.

- Murphy-Bielicki, Schumacher HR. How does patient education affect gout? Clin Rheumatol Pract 1984; 2:77–80.

- Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988; 15:1422–1426.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002; 324:1488–1492.

- Willburger RE, Mysler E, Derbot J, et al. Lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily is comparable to indomethacin 50 mg three times daily for the treatment of acute flares of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007; 46:1126–1132.

- Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon T, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987; 17:301–304.

- Schlesinger N, Moore DF, Sun JD, Schumacher HR Jr. A survey of current evaluation and treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2050–2052.

- Rozenberg S, Lang T, Laatar A, Koeger AC, Orcel P, Bourgerois P. Diversity of opinions on the management of gout in France. A survey of 750 rheumatologists. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1996; 63:255–261.

- Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 18:CD006190.

- Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA 2003; 289:2857–2860.

- Alloway JA, Moriarity MJ, Hoogland YT, Nashel DJ. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:111–113.

- Schumacher HR Jr, Chen LX. Newer therapeutic approaches: gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006; 32:235–244, xii.

- Choi HK. Diet, alcohol, and gout: how do we advise patients given recent developments? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2005; 7:220–226.

- Johnson MW, Mitch WE. The risks of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and the use of uricosuric diuretics. Drugs 1981; 21:220–225.

- Berger L, Yü TF. Renal function in gout. IV. An analysis of 524 gouty subjects including long-term follow-up studies. Am J Med 1975; 59:605–613.

- Stein HB, Hasan A, Fox IH. Ascorbic acid-induced uricosuria. A consequence of megavitamin therapy. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:385–388.

- Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59:109–116.

- Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, Scroggie DA, Harris MD, Alloway JA. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31:2429–2432.

- Sarawate CA, Patel PA, Schumacher HR, Yang W, Brewer KK, Bakst AW. Serum urate levels and gout flares: analysis from managed care data. J Clin Rheumatol 2006; 12:61–65.

- Hande KR, Noone RM, Stone WJ. Severe allopurinol toxicity. Description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Med 1984; 76:47–56.

- Vázquez-Mellado J, Morales EM, Pacheco-Tena C, Burgos-Vargas R. Relation between adverse events associated with allopurinol and renal function in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:981–983.

- Dalbeth N, Kumar S, Stamp L, Gow P. Dose adjustment of allopurinol according to creatinine clearance does not provide adequate control of hyperuricemia in patients with gout. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1646–1650.

- Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:445–451.

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann, RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2450–2461.

- Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, et al. Treatment of chronic gout. Can we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout? J Rheumatol 2001; 28:577–580.

- Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with anti-hyperuricemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51:321–325.

- Pascual E, Sivera F. Time required for disappearance of urate crystals from synovial fluid after successful hypouricaemic treatment relates to the duration of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:1056–1058.

- Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan JI, Herrero-Beites AM, Ruibal A. Effect of urate-lowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47:356–360

- McCarthy GM, Barthelemy CR, Veum JA, Wortmann RL. Influence of antihyperuricemic therapy on the clinical and radiographic progression of gout. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34:1489–1494.

- van Lieshout-Zuidema MF, Breedveld FC. Withdrawal of long-term antihyperuricemic therapy in tophaceous gout. J Rheumatol 1993; 20:1383–1385.

- Bull PW, Scott JT. Intermittent control of hyperuricemia in the treatment of gout. J Rheumatol 1989; 16:1246–1248.

- Murphy-Bielicki, Schumacher HR. How does patient education affect gout? Clin Rheumatol Pract 1984; 2:77–80.

KEY POINTS

- A patient’s comorbidities and other medications should guide the choice of anti-inflammatory agent for acute attacks.

- NSAIDs are the treatment of choice for acute gout attacks; colchicine and corticosteroids are alternatives when NSAIDs are contraindicated.

- Urate-lowering therapy to address underyling hyperuricemia is generally a lifelong commitment, as intermittent therapy can lead to recurrent gout flares.