User login

In a time of great national and global upheaval, increasing social problems, migration, climate crisis, globalization, and increasingly multicultural societies, our patients and their needs are unique, diverse, and changing. We need a new understanding of mental health to be able to adequately meet the demands of an ever-changing world. Treatment exclusively with psychotropic medications or years of psychoanalysis will not meet these needs.

Psychiatrists and psychotherapists feel (and actually have) a social responsibility, particularly in a multifaceted global society. Psychotherapeutic interventions may contribute to a more peaceful society1 by reducing individuals’ inner stress, solving (unconscious) conflicts, and conveying a humanistic worldview. As an integrative and transcultural method, positive psychotherapy has been applied for more than 45 years in more than 60 countries and is an active force within a “positive mental health movement.”2

The term “positive psychotherapy” describes 2 different approaches3: positive psychotherapy (1977) by Nossrat Peseschkian,4 which is a humanistic psychodynamic approach, and positive psychotherapy (2006) by Martin E.P. Seligman, Tayyab Rashid, and Acacia C. Parks,5 which is a more cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach. This article focuses on the first approach.

Why ‘positive’ psychotherapy?

The term “positive” implies that positive psychotherapy focuses on the patient’s possibilities and capacities. Symptoms and disorders are seen as capacities to react to a conflict. The Latin term “positum” or “positivus” is applied in its original meaning—the factual, the given, the actual. Factual and given are not only the disorder, the symptoms, and the problems but also the capacity to become healthy and/or cope with this situation. This positive meaning confronts the patient (and the therapist) with a lesser-known aspect of the illness, but one that is just as important for the understanding and clinical treatment of the affliction: its function, its meaning, and, consequently, its positive aspects.6

Positive psychotherapy is a humanistic psychodynamic psychotherapy approach developed by Nossrat Peseschkian (1933-2010).4,7 Positive psychotherapy has been developed since the 1970s in the clinical setting with neurotic and psychosomatic patients. It integrates approaches of the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy:

- a humanistic view of human beings

- a systemic approach toward culture, work, and environment

- a psychodynamic understanding of disorders

- a practical, goal-oriented approach with some cognitive-behavioral techniques.

The concept of balance

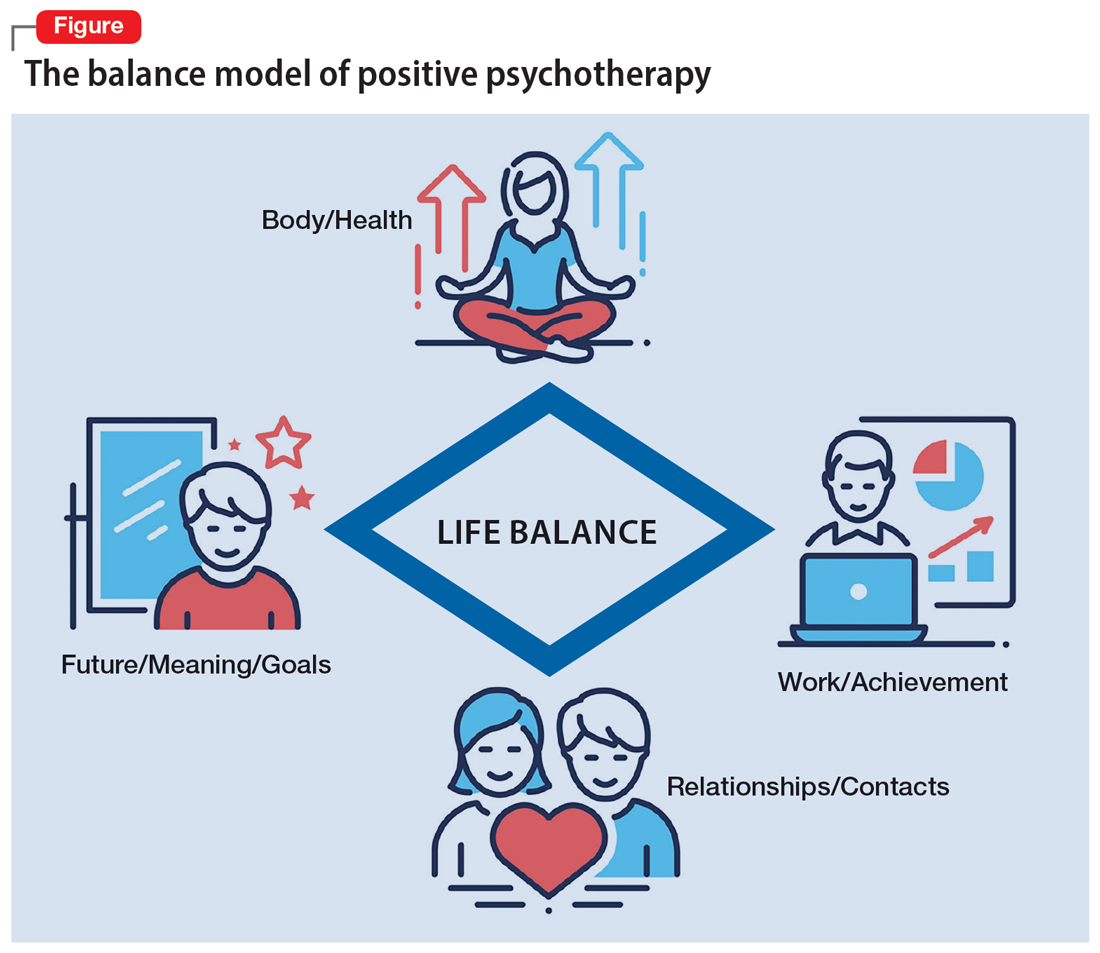

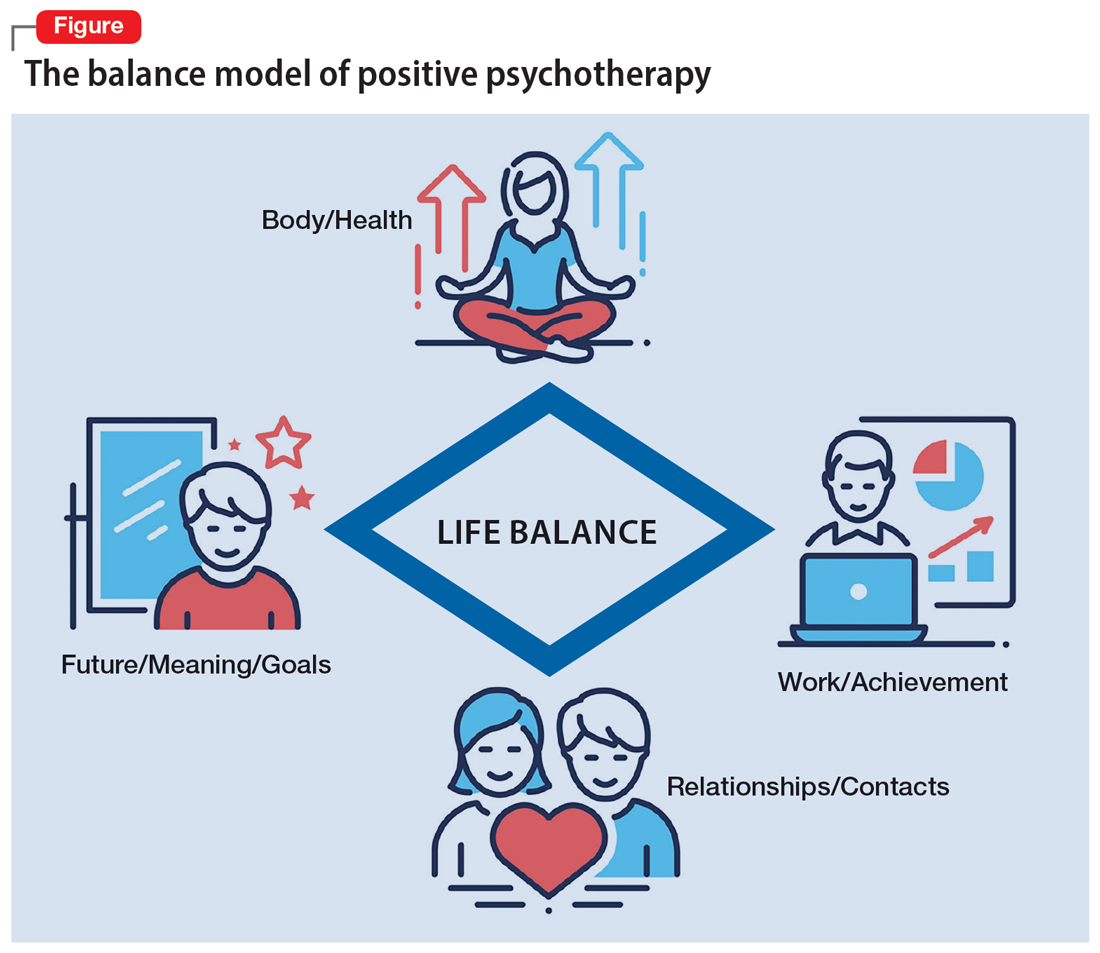

Based on a humanistic view of human beings and the resources every patient possesses, a key concept of positive psychotherapy is the importance of balance in one’s life. The balance model (Figure) is the core of positive psychotherapy and is applied in clinical and nonclinical settings. This model is based on the concept that there are 4 main areas of life in which a human being lives and functions. These areas influence one’s satisfaction in life, one’s feelings of self-worth, and the way one deals with conflicts and challenges. Although all 4 capacities are latent in every human being, depending on one`s education, environment, and zeitgeist, some will be more developed than others. Our life energies, activities, and reactions belong to these 4 areas of life:

- physical: eating, tenderness, sexuality, sleep, relaxation, sports, appearance, clothing

- achievement: work, job, career, money

- relationships: partner, family, friends, acquaintances and strangers, community life

- meaning and future: existential questions, spirituality, religious practices, future plans, fantasy.

A goal of treatment is to help the patient recognize their own resources and mobilize them with the goal of bringing them into a dynamic equilibrium. This goal places value on a balanced distribution of energy (25% to each area), not of time. According to positive psychotherapy, a person does not become ill because one sphere of life is overemphasized but because of the areas that have been neglected. In the case vignette described in the Box, the problem is not the patient’s work but that his physical health, family and friends, and existential questions are being neglected. That the therapist is not critical from the start of treatment is a constructive experience for the patient and is important and fruitful for building the relationship between the therapist and the patient. Instead of emphasizing the deficits or the disorders, the patient and his family hear that he has neglected other areas of life and not developed them yet.

Box

Mr. M, a 52-year-old manager, is “sent” by his wife to see a psychotherapist. “My wife says I am married to my job, and I should spend more time with her and the children. I understand this, but I love my job. It is no stress for me, but a few minutes at home, and I feel totally stressed out,” he says. During the first interview, the therapist asks Mr. M to draw his energy distribution in the balance model (Figure), and it becomes clear he spends more than 80% of his time and energy on his job.

That is not such a surprise for him. But after some explanation, the therapist tells him that he should continue to do so and that it is an ability to be able to spend so much time every day for his job. Mr. M says, “You are the first person to tell me that it is good that I am working so much. I expected you, like all the others, to tell me I must reduce my working hours immediately, go on vacation, etc.”

Continue to: The balance model...

The balance model also embodies the 4 potential sources of self-esteem. Usually, only 1 or 2 areas provide self-esteem, but in the therapeutic process a patient can learn to uncover the neglected areas so that their self-esteem will have additional pillars of support. By emphasizing how therapy can help to develop one’s self-esteem, many patients can be motivated for the therapeutic process. The balance model, with its concept of devoting 25% of one’s energy to each sphere of life, gives the patient a clear vision about their life and how they can be healthy over the long run by avoiding one-sidedness.8

The transcultural approach

In positive psychotherapy, the term “transcultural” (or cross-cultural) means not only consideration of cultural factors when the therapist and patient come from diverse cultural backgrounds (intercultural psychotherapy or “migrant psychotherapy”) but specifically the consideration of cultural factors in every therapeutic relationship, as a therapeutic attitude and consequently as a sociopolitical dimension of our thinking and behavior. This consideration of the uniqueness of each person, of the relativity of human behavior, and of “unity in diversity” is an essential reason positive psychotherapy is not a “Western” method in the sense of “psychological colonization.”9 Rather, this approach is a culture-sensitive method that can be modified to adapt to particular cultures and life situations.

Transcultural positive psychotherapy begins with answering 2 questions: “How are people different?” and “What do all people have in common?”4 During the therapeutic process, the therapist gives examples from other cultures to the patient to help them relativize their own perspective and broaden their repertoire of behavior.

The use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes

A special technique of positive psychotherapy is the therapeutic use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes.10 Often stories from other cultures are used because they offer another perspective when the patient sees none. This has been shown to be highly effective in psychiatric settings, especially in group settings. Psychiatric patients can often easily relate to the images created by stories. In psychiatry and psychotherapy, stories can be a means of changing a patient’s point of view. Such narratives can free up the listener’s feelings and thoughts and often lead to “Aha!” moments. The mirror function of storytelling leads to identification. In the narratives, the reader or listener recognizes themself as well as their needs and situation. They can reflect on the stories without personally becoming the focus of these reflections and remember their own experiences. Stories present solutions that can be models against which one’s own approach can be compared but that also leave room for broader interpretation. Storytelling is particularly useful in bringing about change in patients who are holding fast to old and outworn ideas.

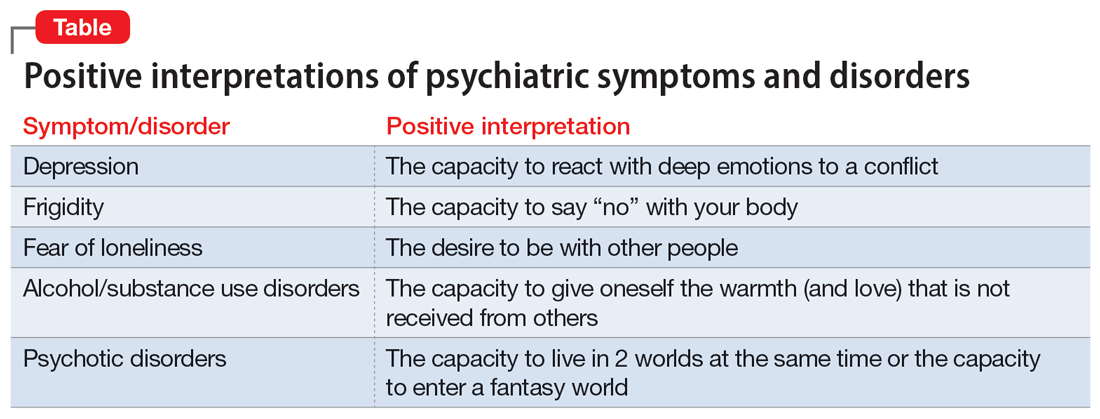

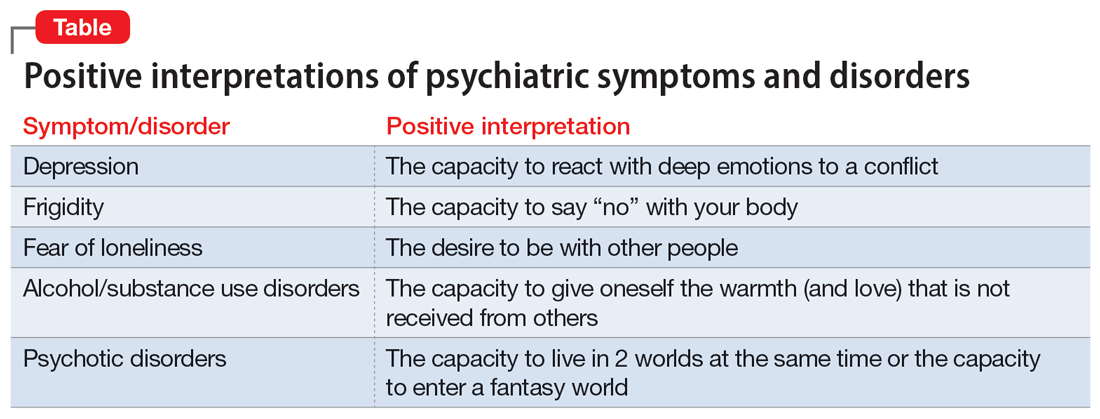

The positive interpretation of disorders

Positive psychotherapy is based on a humanistic view that every human being is good by nature and endowed with unique capacities.11 This positive perspective leads not only to a new quality of relationship between the therapist and patient but also to a new perspective on disorders (Table). Thus, disorders can be “interpreted” in a positive way6: What does the patient unconsciously want to express with their symptoms? What is the function of their disorder? The positive process brings with it a change in perspective to all those concerned: the patient, their family, and the therapist/physician. In this way, one moves from the symptom (which is the disorder and often already has been very thoroughly examined) to the conflict (and the function of the disorder). The positive interpretations are only offered to the patient (“What do you say to this explanation?” “Can you apply this to your own situation?”).

Continue to: This process also helps us...

This process also helps us focus on the “true” patient, who often is not our patient. The patient who comes to us functions as a symptom carrier and can be seen as the “weakest link” in the family chain. The “real patient” is often sitting at home. The positive interpretation of illnesses confronts the patient with the possible function and psychodynamic meaning of their illness for themself and their social milieu, encouraging the patient (and their family) to see their abilities and not merely the pathological aspects.12

Fields of application of positive psychotherapy

As a method positioned between manualized CBT and process-oriented analytical psychotherapy, positive psychotherapy pursues a semi-structured approach in diagnostics (first interview), treatment, posttherapeutic self-help, and training. Positive psychotherapy is applied for the treatment of mood (affective), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders; behavioral syndromes; and, to some extent, personality disorders. Positive psychotherapy has been employed successfully side-by-side with classical individual therapy as well as in the settings of couple, family, and group therapy.13

What makes positive psychotherapy attractive for mental health professionals?

- As a method that integrates the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy, it does not engage in the conflicts between different schools but combines effective elements into a single approach.

- As an integrative approach, it adjusts to the patient and not vice versa. It gives the therapist the possibility of focusing more on either the actual problems (supportive approach) or the basic conflict (psychodynamic approach).

- It uses vocabulary and terms that can be understood by patients from all strata of society.

- As a culturally sensitive method, it can be applied to patients from different cultures and does not require cultural adaptation.

- As a psychodynamic method, it does not stop after early life conflicts have become more conscious but helps the patient to apply the gained insights using practical techniques.

- It starts with positive affirmations and encouragement but does not later “forget” the unconscious conflicts that have led to disorders. It is not perceived as superficial.

- As a method originally coming from psychiatry and medical practice, it builds a bridge between a scientific basis and psychotherapeutic insights. It favors the biopsychosocial approach.

Bottom Line

Positive psychotherapy combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. It is based on a resource-oriented view of human beings in which disorders are interpreted as capacities to react in a specific and unique way to life events and circumstances. Positive psychotherapy can be applied in psychiatry and psychotherapy. This short-term method is easily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Related Resources

- Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33264-8_2

- Tritt K, Loew T, Meyer M, et al. Positive psychotherapy: effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach. Eur J Psychiatry. 1999;13(4):231-241.

- World Association for Positive and Transcultural Psychotherapy. http://www.positum.org

1. Mackenthun G. Passt Psychotherapie an ‚die Gesellschaft’ an? Dynamische Psychiatrie. 1991;24(5-6):326-333.

2. Jeste DV. Foreword: positive mental health. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:vii-xiii.

3. Dobiała E, Winkler P. ‘Positive psychotherapy’ according to Seligman and ‘positive psychotherapy’ according to Peseschkian: a comparison. Int J Psychother. 2016;20(3):5-17.

4. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice of a New Method. Springer; 1987.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychosomatics: Clinical Manual of Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

7. Peseschkian N. Positive psychotherapy. In: Pritz A, ed. Globalized Psychotherapy. Facultas Universitätsverlag; 2002.

8. Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32.

9. Moghaddam FM, Harre R. But is it science? Traditional and alternative approaches to the study of social behavior. World Psychol. 1995;1(4):47-78.

10. Peseschkian N. Oriental Stories as Techniques in Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

11. Cope TA. Positive psychotherapy’s theory of the capacity to know as explication of unconscious contents. J Relig Health. 2009;48(1):79-89.

12. Huebner G. Health-illness from the perspective of positive psychotherapy. Global Psychother. 2021;1(1):57-61.

13. Sinici E. A ‘balance model’ for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Psychother. 2015;19(3):13-19.

In a time of great national and global upheaval, increasing social problems, migration, climate crisis, globalization, and increasingly multicultural societies, our patients and their needs are unique, diverse, and changing. We need a new understanding of mental health to be able to adequately meet the demands of an ever-changing world. Treatment exclusively with psychotropic medications or years of psychoanalysis will not meet these needs.

Psychiatrists and psychotherapists feel (and actually have) a social responsibility, particularly in a multifaceted global society. Psychotherapeutic interventions may contribute to a more peaceful society1 by reducing individuals’ inner stress, solving (unconscious) conflicts, and conveying a humanistic worldview. As an integrative and transcultural method, positive psychotherapy has been applied for more than 45 years in more than 60 countries and is an active force within a “positive mental health movement.”2

The term “positive psychotherapy” describes 2 different approaches3: positive psychotherapy (1977) by Nossrat Peseschkian,4 which is a humanistic psychodynamic approach, and positive psychotherapy (2006) by Martin E.P. Seligman, Tayyab Rashid, and Acacia C. Parks,5 which is a more cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach. This article focuses on the first approach.

Why ‘positive’ psychotherapy?

The term “positive” implies that positive psychotherapy focuses on the patient’s possibilities and capacities. Symptoms and disorders are seen as capacities to react to a conflict. The Latin term “positum” or “positivus” is applied in its original meaning—the factual, the given, the actual. Factual and given are not only the disorder, the symptoms, and the problems but also the capacity to become healthy and/or cope with this situation. This positive meaning confronts the patient (and the therapist) with a lesser-known aspect of the illness, but one that is just as important for the understanding and clinical treatment of the affliction: its function, its meaning, and, consequently, its positive aspects.6

Positive psychotherapy is a humanistic psychodynamic psychotherapy approach developed by Nossrat Peseschkian (1933-2010).4,7 Positive psychotherapy has been developed since the 1970s in the clinical setting with neurotic and psychosomatic patients. It integrates approaches of the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy:

- a humanistic view of human beings

- a systemic approach toward culture, work, and environment

- a psychodynamic understanding of disorders

- a practical, goal-oriented approach with some cognitive-behavioral techniques.

The concept of balance

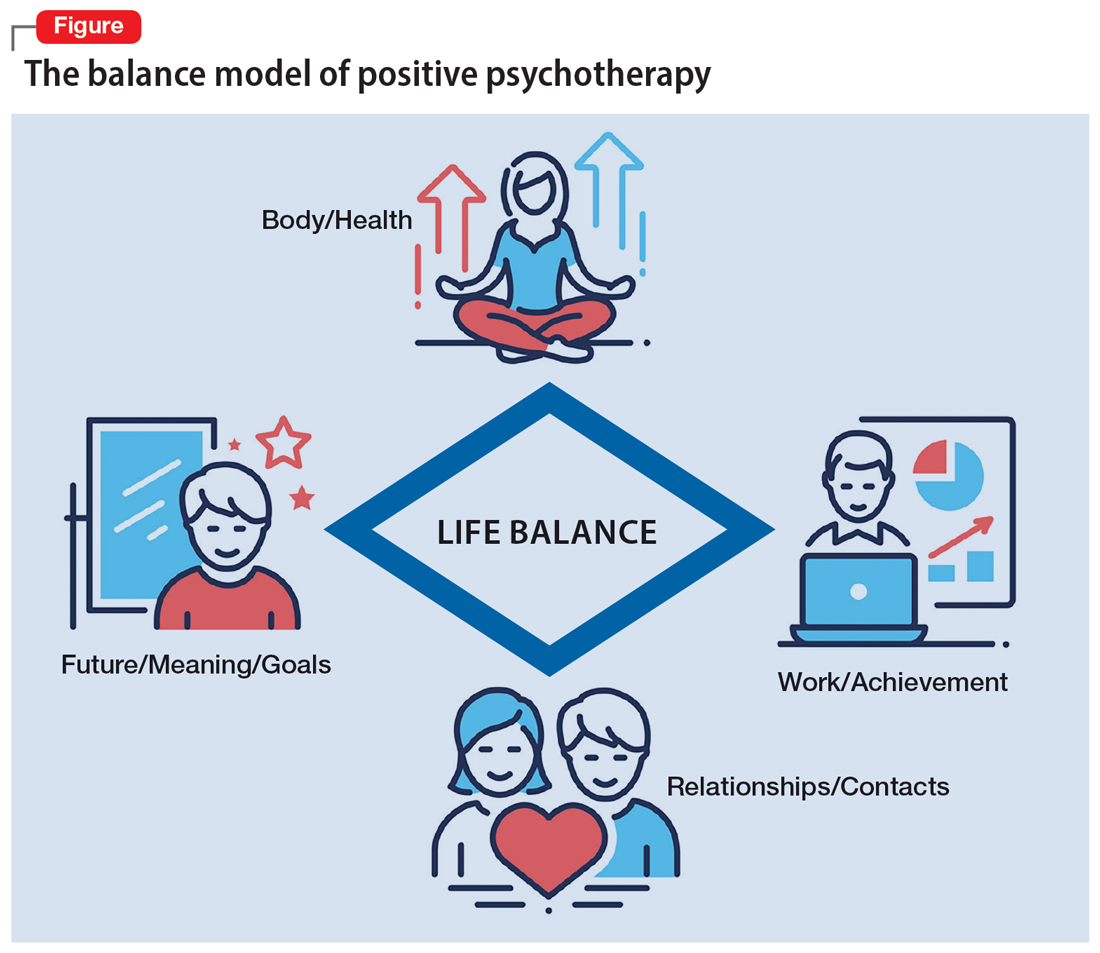

Based on a humanistic view of human beings and the resources every patient possesses, a key concept of positive psychotherapy is the importance of balance in one’s life. The balance model (Figure) is the core of positive psychotherapy and is applied in clinical and nonclinical settings. This model is based on the concept that there are 4 main areas of life in which a human being lives and functions. These areas influence one’s satisfaction in life, one’s feelings of self-worth, and the way one deals with conflicts and challenges. Although all 4 capacities are latent in every human being, depending on one`s education, environment, and zeitgeist, some will be more developed than others. Our life energies, activities, and reactions belong to these 4 areas of life:

- physical: eating, tenderness, sexuality, sleep, relaxation, sports, appearance, clothing

- achievement: work, job, career, money

- relationships: partner, family, friends, acquaintances and strangers, community life

- meaning and future: existential questions, spirituality, religious practices, future plans, fantasy.

A goal of treatment is to help the patient recognize their own resources and mobilize them with the goal of bringing them into a dynamic equilibrium. This goal places value on a balanced distribution of energy (25% to each area), not of time. According to positive psychotherapy, a person does not become ill because one sphere of life is overemphasized but because of the areas that have been neglected. In the case vignette described in the Box, the problem is not the patient’s work but that his physical health, family and friends, and existential questions are being neglected. That the therapist is not critical from the start of treatment is a constructive experience for the patient and is important and fruitful for building the relationship between the therapist and the patient. Instead of emphasizing the deficits or the disorders, the patient and his family hear that he has neglected other areas of life and not developed them yet.

Box

Mr. M, a 52-year-old manager, is “sent” by his wife to see a psychotherapist. “My wife says I am married to my job, and I should spend more time with her and the children. I understand this, but I love my job. It is no stress for me, but a few minutes at home, and I feel totally stressed out,” he says. During the first interview, the therapist asks Mr. M to draw his energy distribution in the balance model (Figure), and it becomes clear he spends more than 80% of his time and energy on his job.

That is not such a surprise for him. But after some explanation, the therapist tells him that he should continue to do so and that it is an ability to be able to spend so much time every day for his job. Mr. M says, “You are the first person to tell me that it is good that I am working so much. I expected you, like all the others, to tell me I must reduce my working hours immediately, go on vacation, etc.”

Continue to: The balance model...

The balance model also embodies the 4 potential sources of self-esteem. Usually, only 1 or 2 areas provide self-esteem, but in the therapeutic process a patient can learn to uncover the neglected areas so that their self-esteem will have additional pillars of support. By emphasizing how therapy can help to develop one’s self-esteem, many patients can be motivated for the therapeutic process. The balance model, with its concept of devoting 25% of one’s energy to each sphere of life, gives the patient a clear vision about their life and how they can be healthy over the long run by avoiding one-sidedness.8

The transcultural approach

In positive psychotherapy, the term “transcultural” (or cross-cultural) means not only consideration of cultural factors when the therapist and patient come from diverse cultural backgrounds (intercultural psychotherapy or “migrant psychotherapy”) but specifically the consideration of cultural factors in every therapeutic relationship, as a therapeutic attitude and consequently as a sociopolitical dimension of our thinking and behavior. This consideration of the uniqueness of each person, of the relativity of human behavior, and of “unity in diversity” is an essential reason positive psychotherapy is not a “Western” method in the sense of “psychological colonization.”9 Rather, this approach is a culture-sensitive method that can be modified to adapt to particular cultures and life situations.

Transcultural positive psychotherapy begins with answering 2 questions: “How are people different?” and “What do all people have in common?”4 During the therapeutic process, the therapist gives examples from other cultures to the patient to help them relativize their own perspective and broaden their repertoire of behavior.

The use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes

A special technique of positive psychotherapy is the therapeutic use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes.10 Often stories from other cultures are used because they offer another perspective when the patient sees none. This has been shown to be highly effective in psychiatric settings, especially in group settings. Psychiatric patients can often easily relate to the images created by stories. In psychiatry and psychotherapy, stories can be a means of changing a patient’s point of view. Such narratives can free up the listener’s feelings and thoughts and often lead to “Aha!” moments. The mirror function of storytelling leads to identification. In the narratives, the reader or listener recognizes themself as well as their needs and situation. They can reflect on the stories without personally becoming the focus of these reflections and remember their own experiences. Stories present solutions that can be models against which one’s own approach can be compared but that also leave room for broader interpretation. Storytelling is particularly useful in bringing about change in patients who are holding fast to old and outworn ideas.

The positive interpretation of disorders

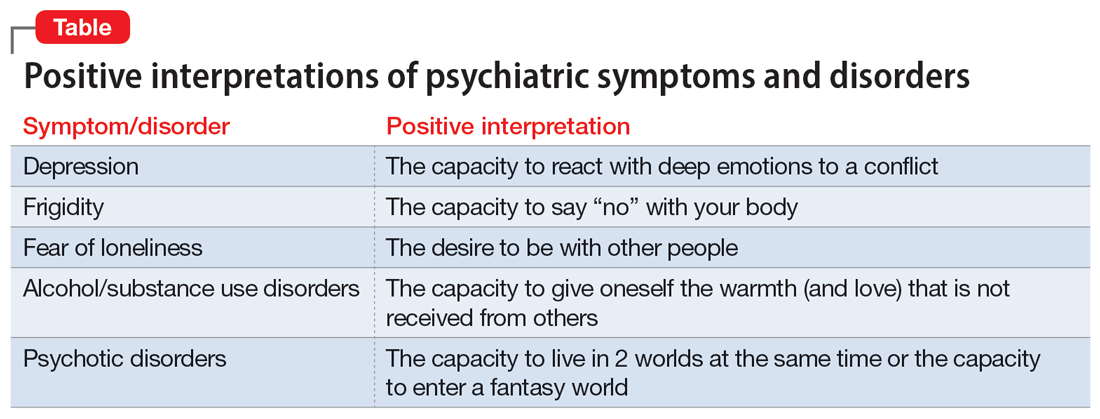

Positive psychotherapy is based on a humanistic view that every human being is good by nature and endowed with unique capacities.11 This positive perspective leads not only to a new quality of relationship between the therapist and patient but also to a new perspective on disorders (Table). Thus, disorders can be “interpreted” in a positive way6: What does the patient unconsciously want to express with their symptoms? What is the function of their disorder? The positive process brings with it a change in perspective to all those concerned: the patient, their family, and the therapist/physician. In this way, one moves from the symptom (which is the disorder and often already has been very thoroughly examined) to the conflict (and the function of the disorder). The positive interpretations are only offered to the patient (“What do you say to this explanation?” “Can you apply this to your own situation?”).

Continue to: This process also helps us...

This process also helps us focus on the “true” patient, who often is not our patient. The patient who comes to us functions as a symptom carrier and can be seen as the “weakest link” in the family chain. The “real patient” is often sitting at home. The positive interpretation of illnesses confronts the patient with the possible function and psychodynamic meaning of their illness for themself and their social milieu, encouraging the patient (and their family) to see their abilities and not merely the pathological aspects.12

Fields of application of positive psychotherapy

As a method positioned between manualized CBT and process-oriented analytical psychotherapy, positive psychotherapy pursues a semi-structured approach in diagnostics (first interview), treatment, posttherapeutic self-help, and training. Positive psychotherapy is applied for the treatment of mood (affective), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders; behavioral syndromes; and, to some extent, personality disorders. Positive psychotherapy has been employed successfully side-by-side with classical individual therapy as well as in the settings of couple, family, and group therapy.13

What makes positive psychotherapy attractive for mental health professionals?

- As a method that integrates the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy, it does not engage in the conflicts between different schools but combines effective elements into a single approach.

- As an integrative approach, it adjusts to the patient and not vice versa. It gives the therapist the possibility of focusing more on either the actual problems (supportive approach) or the basic conflict (psychodynamic approach).

- It uses vocabulary and terms that can be understood by patients from all strata of society.

- As a culturally sensitive method, it can be applied to patients from different cultures and does not require cultural adaptation.

- As a psychodynamic method, it does not stop after early life conflicts have become more conscious but helps the patient to apply the gained insights using practical techniques.

- It starts with positive affirmations and encouragement but does not later “forget” the unconscious conflicts that have led to disorders. It is not perceived as superficial.

- As a method originally coming from psychiatry and medical practice, it builds a bridge between a scientific basis and psychotherapeutic insights. It favors the biopsychosocial approach.

Bottom Line

Positive psychotherapy combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. It is based on a resource-oriented view of human beings in which disorders are interpreted as capacities to react in a specific and unique way to life events and circumstances. Positive psychotherapy can be applied in psychiatry and psychotherapy. This short-term method is easily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Related Resources

- Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33264-8_2

- Tritt K, Loew T, Meyer M, et al. Positive psychotherapy: effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach. Eur J Psychiatry. 1999;13(4):231-241.

- World Association for Positive and Transcultural Psychotherapy. http://www.positum.org

In a time of great national and global upheaval, increasing social problems, migration, climate crisis, globalization, and increasingly multicultural societies, our patients and their needs are unique, diverse, and changing. We need a new understanding of mental health to be able to adequately meet the demands of an ever-changing world. Treatment exclusively with psychotropic medications or years of psychoanalysis will not meet these needs.

Psychiatrists and psychotherapists feel (and actually have) a social responsibility, particularly in a multifaceted global society. Psychotherapeutic interventions may contribute to a more peaceful society1 by reducing individuals’ inner stress, solving (unconscious) conflicts, and conveying a humanistic worldview. As an integrative and transcultural method, positive psychotherapy has been applied for more than 45 years in more than 60 countries and is an active force within a “positive mental health movement.”2

The term “positive psychotherapy” describes 2 different approaches3: positive psychotherapy (1977) by Nossrat Peseschkian,4 which is a humanistic psychodynamic approach, and positive psychotherapy (2006) by Martin E.P. Seligman, Tayyab Rashid, and Acacia C. Parks,5 which is a more cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach. This article focuses on the first approach.

Why ‘positive’ psychotherapy?

The term “positive” implies that positive psychotherapy focuses on the patient’s possibilities and capacities. Symptoms and disorders are seen as capacities to react to a conflict. The Latin term “positum” or “positivus” is applied in its original meaning—the factual, the given, the actual. Factual and given are not only the disorder, the symptoms, and the problems but also the capacity to become healthy and/or cope with this situation. This positive meaning confronts the patient (and the therapist) with a lesser-known aspect of the illness, but one that is just as important for the understanding and clinical treatment of the affliction: its function, its meaning, and, consequently, its positive aspects.6

Positive psychotherapy is a humanistic psychodynamic psychotherapy approach developed by Nossrat Peseschkian (1933-2010).4,7 Positive psychotherapy has been developed since the 1970s in the clinical setting with neurotic and psychosomatic patients. It integrates approaches of the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy:

- a humanistic view of human beings

- a systemic approach toward culture, work, and environment

- a psychodynamic understanding of disorders

- a practical, goal-oriented approach with some cognitive-behavioral techniques.

The concept of balance

Based on a humanistic view of human beings and the resources every patient possesses, a key concept of positive psychotherapy is the importance of balance in one’s life. The balance model (Figure) is the core of positive psychotherapy and is applied in clinical and nonclinical settings. This model is based on the concept that there are 4 main areas of life in which a human being lives and functions. These areas influence one’s satisfaction in life, one’s feelings of self-worth, and the way one deals with conflicts and challenges. Although all 4 capacities are latent in every human being, depending on one`s education, environment, and zeitgeist, some will be more developed than others. Our life energies, activities, and reactions belong to these 4 areas of life:

- physical: eating, tenderness, sexuality, sleep, relaxation, sports, appearance, clothing

- achievement: work, job, career, money

- relationships: partner, family, friends, acquaintances and strangers, community life

- meaning and future: existential questions, spirituality, religious practices, future plans, fantasy.

A goal of treatment is to help the patient recognize their own resources and mobilize them with the goal of bringing them into a dynamic equilibrium. This goal places value on a balanced distribution of energy (25% to each area), not of time. According to positive psychotherapy, a person does not become ill because one sphere of life is overemphasized but because of the areas that have been neglected. In the case vignette described in the Box, the problem is not the patient’s work but that his physical health, family and friends, and existential questions are being neglected. That the therapist is not critical from the start of treatment is a constructive experience for the patient and is important and fruitful for building the relationship between the therapist and the patient. Instead of emphasizing the deficits or the disorders, the patient and his family hear that he has neglected other areas of life and not developed them yet.

Box

Mr. M, a 52-year-old manager, is “sent” by his wife to see a psychotherapist. “My wife says I am married to my job, and I should spend more time with her and the children. I understand this, but I love my job. It is no stress for me, but a few minutes at home, and I feel totally stressed out,” he says. During the first interview, the therapist asks Mr. M to draw his energy distribution in the balance model (Figure), and it becomes clear he spends more than 80% of his time and energy on his job.

That is not such a surprise for him. But after some explanation, the therapist tells him that he should continue to do so and that it is an ability to be able to spend so much time every day for his job. Mr. M says, “You are the first person to tell me that it is good that I am working so much. I expected you, like all the others, to tell me I must reduce my working hours immediately, go on vacation, etc.”

Continue to: The balance model...

The balance model also embodies the 4 potential sources of self-esteem. Usually, only 1 or 2 areas provide self-esteem, but in the therapeutic process a patient can learn to uncover the neglected areas so that their self-esteem will have additional pillars of support. By emphasizing how therapy can help to develop one’s self-esteem, many patients can be motivated for the therapeutic process. The balance model, with its concept of devoting 25% of one’s energy to each sphere of life, gives the patient a clear vision about their life and how they can be healthy over the long run by avoiding one-sidedness.8

The transcultural approach

In positive psychotherapy, the term “transcultural” (or cross-cultural) means not only consideration of cultural factors when the therapist and patient come from diverse cultural backgrounds (intercultural psychotherapy or “migrant psychotherapy”) but specifically the consideration of cultural factors in every therapeutic relationship, as a therapeutic attitude and consequently as a sociopolitical dimension of our thinking and behavior. This consideration of the uniqueness of each person, of the relativity of human behavior, and of “unity in diversity” is an essential reason positive psychotherapy is not a “Western” method in the sense of “psychological colonization.”9 Rather, this approach is a culture-sensitive method that can be modified to adapt to particular cultures and life situations.

Transcultural positive psychotherapy begins with answering 2 questions: “How are people different?” and “What do all people have in common?”4 During the therapeutic process, the therapist gives examples from other cultures to the patient to help them relativize their own perspective and broaden their repertoire of behavior.

The use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes

A special technique of positive psychotherapy is the therapeutic use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes.10 Often stories from other cultures are used because they offer another perspective when the patient sees none. This has been shown to be highly effective in psychiatric settings, especially in group settings. Psychiatric patients can often easily relate to the images created by stories. In psychiatry and psychotherapy, stories can be a means of changing a patient’s point of view. Such narratives can free up the listener’s feelings and thoughts and often lead to “Aha!” moments. The mirror function of storytelling leads to identification. In the narratives, the reader or listener recognizes themself as well as their needs and situation. They can reflect on the stories without personally becoming the focus of these reflections and remember their own experiences. Stories present solutions that can be models against which one’s own approach can be compared but that also leave room for broader interpretation. Storytelling is particularly useful in bringing about change in patients who are holding fast to old and outworn ideas.

The positive interpretation of disorders

Positive psychotherapy is based on a humanistic view that every human being is good by nature and endowed with unique capacities.11 This positive perspective leads not only to a new quality of relationship between the therapist and patient but also to a new perspective on disorders (Table). Thus, disorders can be “interpreted” in a positive way6: What does the patient unconsciously want to express with their symptoms? What is the function of their disorder? The positive process brings with it a change in perspective to all those concerned: the patient, their family, and the therapist/physician. In this way, one moves from the symptom (which is the disorder and often already has been very thoroughly examined) to the conflict (and the function of the disorder). The positive interpretations are only offered to the patient (“What do you say to this explanation?” “Can you apply this to your own situation?”).

Continue to: This process also helps us...

This process also helps us focus on the “true” patient, who often is not our patient. The patient who comes to us functions as a symptom carrier and can be seen as the “weakest link” in the family chain. The “real patient” is often sitting at home. The positive interpretation of illnesses confronts the patient with the possible function and psychodynamic meaning of their illness for themself and their social milieu, encouraging the patient (and their family) to see their abilities and not merely the pathological aspects.12

Fields of application of positive psychotherapy

As a method positioned between manualized CBT and process-oriented analytical psychotherapy, positive psychotherapy pursues a semi-structured approach in diagnostics (first interview), treatment, posttherapeutic self-help, and training. Positive psychotherapy is applied for the treatment of mood (affective), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders; behavioral syndromes; and, to some extent, personality disorders. Positive psychotherapy has been employed successfully side-by-side with classical individual therapy as well as in the settings of couple, family, and group therapy.13

What makes positive psychotherapy attractive for mental health professionals?

- As a method that integrates the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy, it does not engage in the conflicts between different schools but combines effective elements into a single approach.

- As an integrative approach, it adjusts to the patient and not vice versa. It gives the therapist the possibility of focusing more on either the actual problems (supportive approach) or the basic conflict (psychodynamic approach).

- It uses vocabulary and terms that can be understood by patients from all strata of society.

- As a culturally sensitive method, it can be applied to patients from different cultures and does not require cultural adaptation.

- As a psychodynamic method, it does not stop after early life conflicts have become more conscious but helps the patient to apply the gained insights using practical techniques.

- It starts with positive affirmations and encouragement but does not later “forget” the unconscious conflicts that have led to disorders. It is not perceived as superficial.

- As a method originally coming from psychiatry and medical practice, it builds a bridge between a scientific basis and psychotherapeutic insights. It favors the biopsychosocial approach.

Bottom Line

Positive psychotherapy combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. It is based on a resource-oriented view of human beings in which disorders are interpreted as capacities to react in a specific and unique way to life events and circumstances. Positive psychotherapy can be applied in psychiatry and psychotherapy. This short-term method is easily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Related Resources

- Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33264-8_2

- Tritt K, Loew T, Meyer M, et al. Positive psychotherapy: effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach. Eur J Psychiatry. 1999;13(4):231-241.

- World Association for Positive and Transcultural Psychotherapy. http://www.positum.org

1. Mackenthun G. Passt Psychotherapie an ‚die Gesellschaft’ an? Dynamische Psychiatrie. 1991;24(5-6):326-333.

2. Jeste DV. Foreword: positive mental health. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:vii-xiii.

3. Dobiała E, Winkler P. ‘Positive psychotherapy’ according to Seligman and ‘positive psychotherapy’ according to Peseschkian: a comparison. Int J Psychother. 2016;20(3):5-17.

4. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice of a New Method. Springer; 1987.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychosomatics: Clinical Manual of Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

7. Peseschkian N. Positive psychotherapy. In: Pritz A, ed. Globalized Psychotherapy. Facultas Universitätsverlag; 2002.

8. Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32.

9. Moghaddam FM, Harre R. But is it science? Traditional and alternative approaches to the study of social behavior. World Psychol. 1995;1(4):47-78.

10. Peseschkian N. Oriental Stories as Techniques in Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

11. Cope TA. Positive psychotherapy’s theory of the capacity to know as explication of unconscious contents. J Relig Health. 2009;48(1):79-89.

12. Huebner G. Health-illness from the perspective of positive psychotherapy. Global Psychother. 2021;1(1):57-61.

13. Sinici E. A ‘balance model’ for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Psychother. 2015;19(3):13-19.

1. Mackenthun G. Passt Psychotherapie an ‚die Gesellschaft’ an? Dynamische Psychiatrie. 1991;24(5-6):326-333.

2. Jeste DV. Foreword: positive mental health. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:vii-xiii.

3. Dobiała E, Winkler P. ‘Positive psychotherapy’ according to Seligman and ‘positive psychotherapy’ according to Peseschkian: a comparison. Int J Psychother. 2016;20(3):5-17.

4. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice of a New Method. Springer; 1987.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Peseschkian N. Positive Psychosomatics: Clinical Manual of Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

7. Peseschkian N. Positive psychotherapy. In: Pritz A, ed. Globalized Psychotherapy. Facultas Universitätsverlag; 2002.

8. Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32.

9. Moghaddam FM, Harre R. But is it science? Traditional and alternative approaches to the study of social behavior. World Psychol. 1995;1(4):47-78.

10. Peseschkian N. Oriental Stories as Techniques in Positive Psychotherapy. AuthorHouse; 2016.

11. Cope TA. Positive psychotherapy’s theory of the capacity to know as explication of unconscious contents. J Relig Health. 2009;48(1):79-89.

12. Huebner G. Health-illness from the perspective of positive psychotherapy. Global Psychother. 2021;1(1):57-61.

13. Sinici E. A ‘balance model’ for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Psychother. 2015;19(3):13-19.