User login

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

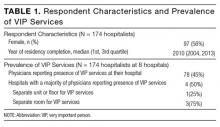

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

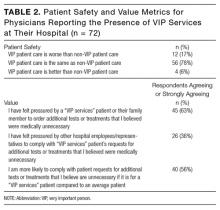

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Recent publications in the medical literature and lay press have stirred controversy regarding the use of inpatient ‘very important person’ (VIP) services.1-3 The term “VIP services” often refers to select conveniences offered in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services provided by a hospital. Examples include additional space, enhanced facilities, specific comforts, or personal support. In some instances, these amenities may only be provided to patients who have close financial, social, or professional relationships with the hospital.

How VIP patients interact with their health system to obtain VIP services has raised unique concerns. Some have speculated that the presence of a VIP patient may be disruptive to the care of non-VIP patients, while others have cautioned physicians about potential dangers to the VIP patients themselves.4-6 Despite much being written on the topics of VIP patients and services in both the lay and academic press, our literature review identified only 1 study on the topic, which cataloged the preferential treatment of VIP patients in the emergency department.6 We are unaware of any investigations of VIP-service use in the inpatient setting. Through a multisite survey of hospital medicine physicians, we assessed physician viewpoints and behavior regarding VIP services.

METHODS

The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN) is a nation-wide learning organization focused on measuring and improving the outcomes of hospitalized patients.7 We surveyed hospitalists from 8 HOMERuN hospitals (Appendix 1). The survey instrument contained 4 sections: nonidentifying respondent demographics, local use of VIP services, reported physician perceptions of VIP services, and case-based assessments (Appendix 2). Survey questions and individual cases were developed by study authors and based on real scenarios and concerns provided by front-line clinical providers. Content, length, and reliability of physician understanding were assessed by a 5-person focus group consisting of physicians not included in the survey population.

Subjects were identified via administrative rosters from each HOMERuN site. Surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey, and results were analyzed descriptively. Populations were compared via the Fisher exact test. “VIP services” were defined as conveniences provided in addition to the assumed basic level of care and services (eg, private or luxury-style rooms, access to a special menu, better views, dedicated personal care attendants, hospital liaisons). VIP patients were defined as those patients receiving VIP services. A hospital was identified as providing VIP services if 50% or more of respondents from that site reported the presence of VIP services.

RESULTS

Of 366 hospitalists contacted, 160 completed the survey (44%). Respondent characteristics and reported prevalence of VIP services are demonstrated in Table 1. In total, 78 respondents (45%) reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital. Of the 8 sites surveyed, a majority of physicians at 4 sites (50%) reported presence of VIP services.

Of respondents reporting the presence of VIP services at their hospital, a majority felt that, from a patient safety perspective, the care received by VIP patients was the same as care received by non-VIP patients (Table 2). A majority reported they had felt pressured by a VIP patient or a family member to order additional tests or treatments that the physician believed were medically unnecessary and that they would be more likely to comply with VIP patient’s requests for tests or treatments they felt were unnecessary. More than one-third (36%) felt pressured by other hospital employees or representatives to comply with VIP services patient’s requests for additional tests or treatments that the physicians believed were medically unnecessary.

When presented the case of a VIP patient with community-acquired pneumonia who is clinically stable for discharge but expressing concerns about leaving the hospital, 61 (38%) respondents reported they would not discharge this patient home: 39 of 70 (55.7%) who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital, and 22 of 91 (24.2%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P < 0.001). Of those who reported they would not discharge this patient home, 37 (61%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s connection to the Board of Trustees; 48 (79%) reported the reason for this related to the patient’s concerns; 9 (15%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns regarding medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

When presented the case of a VIP patient with acute pulmonary embolism who is medically ready for discharge with primary care physician-approved anticoagulation and discharge plans but for whom their family requests additional consultations and inpatient hypercoagulable workup, 33 (21%) respondents reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation: 17 of 69 (24.6%) who reported the presence of VIP services their hospital, and 16 of 91 (17.6%) who reported the absence of VIP services (P = 0.33). Of those who reported they would order additional testing and specialist consultation, 14 (42%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s financial connections to the hospital; 30 (91%) reported the reason for this related to the family’s concerns; 3 (9%) reported the reason for this related to their own concerns about the medical details of the patient’s case (respondents could select more than 1 reason).

DISCUSSION

In our study, a majority of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital felt pressured by VIP patients or their family members to perform unnecessary testing or treatment. While this study was not designed to quantify the burden of unnecessary care for VIP patients, our results have implications for individual patients and public health, including potential effects on resource availability, the identification of clinically irrelevant incidental findings, and short- and long-term medical complications of procedures, testing and radiation exposure.

Prior publications have advocated that physicians and hospitals should not allow VIP status to influence management decisions.3,5 We found that more than one-third of physicians who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported receiving pressure from hospital representatives to provide care to VIP patients that was not medically indicated. These findings highlight an example of the tension faced by physicians who are caught between patient requests and the delivery of value-based care. This potential conflict may be amplified particularly for those patients with close financial, social, or professional ties to the hospitals (and physicians) providing their care. These results suggest the need for physicians, administrators, and patients to work together to address the potential blurring of ethical boundaries created by VIP relationships. Prevention of harm and avoidance of placing physicians in morally distressing situations are common goals for all involved parties.

Efforts to reduce unnecessary care have predominantly focused on structural and knowledge-based drivers.4,8,9 Our results highlight the presence of additional forces. A majority of physician respondents who reported the presence of VIP services at their hospital also reported that they would be more likely to comply with requests for unnecessary care for a VIP patient as compared to a non-VIP patient. Furthermore, in case-based questions about the requests of a VIP patient and their family for additional unnecessary care, a significant portion of physicians who reported they would comply with these requests listed the VIP status of the patient or family as a factor underlying this decision. Only a minority of physicians reported their decision to provide additional care was the result of their own medically-based concerns. Because these cases were hypothetical and we did not include comparator cases involving non-VIP patients, it remains uncertain whether the observed perceptions accurately reflect real-world differences in the care of VIP and non-VIP patients. Nonetheless, our findings emphasize the importance of better understanding the social drivers of overuse and physician communication strategies related to medically inappropriate tests.10,11

Demand for unnecessary testing may be driven by the mentality that “more is better.”12 Contrary to this belief, provision of unnecessary care can increase the risk of patient harm.13 Despite physician respondents reporting that VIP patients requested and/or received additional unnecessary care, a majority of respondents felt that patient safety for VIP patients was equivalent to that for non-VIP patients. As we assessed only physician perceptions of safety, which may not necessarily correlate with actual safety, further research in this area is needed.

Our study was limited by several factors. While our study population included hospitalists from 8 geographically broad hospitals, including university, safety net, and community hospitals, study responses may not be reflective of nationwide trends. Our response rate may limit our ability to generalize conclusions beyond respondents. Second, our study captured physician perceptions of behavior and safety rather than actually measuring practice and outcomes. Studies comparing physician practice patterns and outcomes between VIP and non-VIP patients would be informative. Additionally, despite our inclusive survey design process, our survey was not validated, and it is possible that our questions were not interpreted as intended. Lastly, despite the anonymous nature of our survey, physicians may have felt compelled to respond in a particular way due to conflicting professional, financial, or social factors.

Our findings provide initial insight into how care for the VIP patient may present unique challenges for physicians, hospitals, and society by systematizing care inequities, as well as potentially incentivizing low-value care practices. Whether these imbalances produce clinical harms or benefits remains worthy of future studies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

1. Bernstein N. Chefs, butlers, marble baths: Hospitals vie for the affluent. New York Times. January 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/nyregion/chefs-butlers-and-marble-baths-not-your-average-hospital-room.html. Accessed February 1, 2017.

2. Kennedy DW, Kagan SH, Abramson KB, Boberick C, Kaiser LR. Academic medicine amenities unit: developing a model to integrate academic medical care with luxury hotel services. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):185-191. PubMed

3. Alfandre D, Clever S, Farber NJ, Hughes MT, Redstone P, Lehmann LS. Caring for ‘very important patients’--ethical dilemmas and suggestions for practical management. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):143-147. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Martin A, Bostic JQ, Pruett K. The V.I.P.: hazard and promise in treating “special” patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):366-369. PubMed

6. Smally AJ, Carroll B, Carius M, Tilden F, Werdmann M. Treatment of VIPs. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(4):397-398. PubMed

7. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The hospital medicine reengineering network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. PubMed

8. Caverly TJ, Combs BP, Moriates C, Shah N, Grady D. Too much medicine happens too often: the teachable moment and a call for manuscripts from clinical trainees. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):8-9. PubMed

9. Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare pioneer accountable care organization program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. PubMed

10. Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, Timmermans S, Heritage J, Kravitz RL. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388. PubMed

11. Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):285-293. PubMed

12. Korenstein D. Patient perception of benefits and harms: the Achilles heel of high-value care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):287-288. PubMed

13. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine