User login

May 20 of this plague year, Reuters reported the death of a 32-year-old Florida nurse who had worked tirelessly to treat patients with COVID-19.1 The presumption is that, like so many selfless health care providers (HCPs), this nurse was exposed to and then sadly succumbed to the virus. That presumption would be wrong: COVID-19 did not take his young life. The other pandemic—addiction— did. Bereaved friends and family reported that the nurse had been in recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) before the onslaught of the public health crisis. The chronicle of his relapse is instructive for the devastating effect COVID-19 has had on persons struggling with addiction, even those like the nurse who was in sustained remission from OUD with a bright future.

Many of the themes are familiar to HCPs and have been the subject of prior columns in this COVID-19 series. The nurse experienced acute stress symptoms, such as nightmares from the repeated crises of sick and dying patients in the intensive care unit where he worked.2 Like so many other HCPs, while he was desperately trying to save others, he also worried about having sufficient access to appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Most relevant to this column, the caregiver was unable to access his primary source of support for his sobriety—attendance at 12-step meetings. Social distancing, which is one of the only proven means we have of reducing transmission of the virus, has had unintended consequences. Although many have found virtual connections rewarding, this nurse needed the curtailed face-to-face contact. The courage that had led him to volunteer for hazardous duty unwontedly resulted in his estrangement: Friends feared that he would expose them to the virus, and he worried that he would expose his family to danger. As in the 1918 flu pandemic, the humans we depend on for reality testing and companionship have been cruelly transformed into potential vectors of the virus.3

Isolation is the worst of all possible counselors as the great Spanish philosopher of alienation Miguel de Unamuno has argued. The deceptive promise of a rapid deliverance from anxiety and pain that substances of abuse proffer apparently led the nurse back to opioids. The virtue of being clean permitted the dirty drug to take advantage of the nurses’ reduced physiologic tolerance to opioids. It is suspected but not confirmed that he fatally overdosed alone in his car.

This Florida nurse is an especially tragic example of a terrible phenomenon being repeated all over the country. And the epidemic of substance use disorders (SUDs) related to COVID-19 is not confined to the US; there are similar reports from other afflicted nations, making addiction truly the other pandemic.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 13.3% of American adults have started or increased their substance use as a means of managing the negative emotions associated with the pandemic.5 Also from March to May 2020, researchers in Baltimore found a 17.6% increase in suspected overdoses in counties advising social distancing and/or mandating stay at home orders.5

These data reinforce a well-known maxim in the addiction community that “addiction is a disease of isolation.”6-8 The burden of the lockdown falls harder on many of the patients we treat in the federal health care system whose other mental and physical health conditions, including chronic pain, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder already placed them at elevated risk of SUDs.9 Director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse Nora Volkow, MD, recently traced the well-known arc from isolation to increased use of drugs and alcohol.10 Isolation is stressful and amplifies negative thoughts, dysphoria, and fearful emotions, which are recognized triggers for the use of substances of abuse. The usually available means of coping with craving, and in many cases withdrawal, such as prescribed medications, visits to therapists, participation in support groups are either not available or much more difficult to access.10 Nor are those without a current or even historical SUD immune to the psychosocial pressures of the pandemic: Isolation also constitutes a risk for the development of de novo addiction particularly among already marginalized groups, such as the elderly and disabled.

The federal government has initiated several important measures to reduce the adverse impact of isolation on persons with SUDs. The Drug Enforcement Administration is exempting qualified practitioners of medication-assisted treatment from the in-person evaluation that is usually required for the prescription of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. This exemption applies to both established patient prescriptions for buprenorphine and new buprenorphine patient prescriptions.11 These and other administrative contingencies at the federal government level can assist persons with OUD to continue to receive medicationassisted treatment.

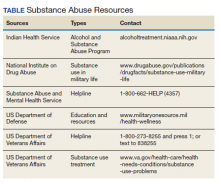

As individual clinicians in federal practice, we alone cannot engineer such major policy accommodations in response to COVID-19, yet we can still make a difference in the lives of our patients. We can focus a few minutes of our telehealth interactions on checking in with patients who have a history or a current SUD. We can remember to use evidence-based screens for these patients and those with other risk factors to detect drug or alcohol use before it becomes a disorder. And we can identify and refer not only patients but also our beleaguered colleagues who feel alone at sea—to the many lifelines our agencies have cast into what other commentators have referred to as a Perfect Storm of COVID-19 and the opioid crisis (Table).12

1. Borter G. A nurse struggled with COVID-19 trauma. He was found dead in his car. Reuters. May 20, 2020. https:// www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-nurse -death-insigh/a-nurse-struggled-with-covid-19-trauma-he -was-found-dead-in-his-car-idUSKBN22W1JD Accessed September 15, 2020.

2. Geppert CMA. The duty to care and its exceptions in a pandemic. Fed Pract. 2020;37(5):210-211.

3. Kim NY. How the 1918 pandemic frayed social bonds. The Atlantic. March 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com /family/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-loneliness-and-mistrust -1918-flu-pandemic-quarantine/609163. Accessed September 18, 2020.

4. Jemberie WB, Stewart Williams J, Eriksson M, et al. Substance use disorders and COVID-19: multi-faceted problems which require multi-pronged solutions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:714. Published 2020 Jul 21. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714

5. Alter A, Yeager C. COVID-19 impact on US national overdose crises. http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020 /ODMAP-Report-June-2020.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed September 18, 2020.

6. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. Published 2020 Aug 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

7. Grinspoon P. A tale of two epidemics: when COVID-19 and opioid addiction collide. https://www.health.harvard.edu /blog/a-tale-of-two-epidemics-when-covid-19-and-opioid -addiction-collide-2020042019569. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020

8. Bebinger M. Addiction is “a disease of isolation”—so pandemic puts recovery at risk. https://khn.org/news/addiction -is-a-disease-of-isolation-so-pandemic-puts-recovery-at-risk. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020.

9. National Institute of Drug Abuse. Substance abuse and military life. DrugFacts. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications /drugfacts/substance-use-military-life. Published October 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020.

10. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62. doi:10.7326/M20-1212

11. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. FAQS: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. https:// www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing -and-dispensing.pdf. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2020.

12. Spagnolo PA, Montemitro C, Leggio L. New challenges in addiction medicine: COVID-19 infection in patients with alcohol and substance usedisorders-the perfect storm. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):805-807. doi:10.1176/appi. ajp.2020.20040417

May 20 of this plague year, Reuters reported the death of a 32-year-old Florida nurse who had worked tirelessly to treat patients with COVID-19.1 The presumption is that, like so many selfless health care providers (HCPs), this nurse was exposed to and then sadly succumbed to the virus. That presumption would be wrong: COVID-19 did not take his young life. The other pandemic—addiction— did. Bereaved friends and family reported that the nurse had been in recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) before the onslaught of the public health crisis. The chronicle of his relapse is instructive for the devastating effect COVID-19 has had on persons struggling with addiction, even those like the nurse who was in sustained remission from OUD with a bright future.

Many of the themes are familiar to HCPs and have been the subject of prior columns in this COVID-19 series. The nurse experienced acute stress symptoms, such as nightmares from the repeated crises of sick and dying patients in the intensive care unit where he worked.2 Like so many other HCPs, while he was desperately trying to save others, he also worried about having sufficient access to appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Most relevant to this column, the caregiver was unable to access his primary source of support for his sobriety—attendance at 12-step meetings. Social distancing, which is one of the only proven means we have of reducing transmission of the virus, has had unintended consequences. Although many have found virtual connections rewarding, this nurse needed the curtailed face-to-face contact. The courage that had led him to volunteer for hazardous duty unwontedly resulted in his estrangement: Friends feared that he would expose them to the virus, and he worried that he would expose his family to danger. As in the 1918 flu pandemic, the humans we depend on for reality testing and companionship have been cruelly transformed into potential vectors of the virus.3

Isolation is the worst of all possible counselors as the great Spanish philosopher of alienation Miguel de Unamuno has argued. The deceptive promise of a rapid deliverance from anxiety and pain that substances of abuse proffer apparently led the nurse back to opioids. The virtue of being clean permitted the dirty drug to take advantage of the nurses’ reduced physiologic tolerance to opioids. It is suspected but not confirmed that he fatally overdosed alone in his car.

This Florida nurse is an especially tragic example of a terrible phenomenon being repeated all over the country. And the epidemic of substance use disorders (SUDs) related to COVID-19 is not confined to the US; there are similar reports from other afflicted nations, making addiction truly the other pandemic.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 13.3% of American adults have started or increased their substance use as a means of managing the negative emotions associated with the pandemic.5 Also from March to May 2020, researchers in Baltimore found a 17.6% increase in suspected overdoses in counties advising social distancing and/or mandating stay at home orders.5

These data reinforce a well-known maxim in the addiction community that “addiction is a disease of isolation.”6-8 The burden of the lockdown falls harder on many of the patients we treat in the federal health care system whose other mental and physical health conditions, including chronic pain, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder already placed them at elevated risk of SUDs.9 Director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse Nora Volkow, MD, recently traced the well-known arc from isolation to increased use of drugs and alcohol.10 Isolation is stressful and amplifies negative thoughts, dysphoria, and fearful emotions, which are recognized triggers for the use of substances of abuse. The usually available means of coping with craving, and in many cases withdrawal, such as prescribed medications, visits to therapists, participation in support groups are either not available or much more difficult to access.10 Nor are those without a current or even historical SUD immune to the psychosocial pressures of the pandemic: Isolation also constitutes a risk for the development of de novo addiction particularly among already marginalized groups, such as the elderly and disabled.

The federal government has initiated several important measures to reduce the adverse impact of isolation on persons with SUDs. The Drug Enforcement Administration is exempting qualified practitioners of medication-assisted treatment from the in-person evaluation that is usually required for the prescription of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. This exemption applies to both established patient prescriptions for buprenorphine and new buprenorphine patient prescriptions.11 These and other administrative contingencies at the federal government level can assist persons with OUD to continue to receive medicationassisted treatment.

As individual clinicians in federal practice, we alone cannot engineer such major policy accommodations in response to COVID-19, yet we can still make a difference in the lives of our patients. We can focus a few minutes of our telehealth interactions on checking in with patients who have a history or a current SUD. We can remember to use evidence-based screens for these patients and those with other risk factors to detect drug or alcohol use before it becomes a disorder. And we can identify and refer not only patients but also our beleaguered colleagues who feel alone at sea—to the many lifelines our agencies have cast into what other commentators have referred to as a Perfect Storm of COVID-19 and the opioid crisis (Table).12

May 20 of this plague year, Reuters reported the death of a 32-year-old Florida nurse who had worked tirelessly to treat patients with COVID-19.1 The presumption is that, like so many selfless health care providers (HCPs), this nurse was exposed to and then sadly succumbed to the virus. That presumption would be wrong: COVID-19 did not take his young life. The other pandemic—addiction— did. Bereaved friends and family reported that the nurse had been in recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) before the onslaught of the public health crisis. The chronicle of his relapse is instructive for the devastating effect COVID-19 has had on persons struggling with addiction, even those like the nurse who was in sustained remission from OUD with a bright future.

Many of the themes are familiar to HCPs and have been the subject of prior columns in this COVID-19 series. The nurse experienced acute stress symptoms, such as nightmares from the repeated crises of sick and dying patients in the intensive care unit where he worked.2 Like so many other HCPs, while he was desperately trying to save others, he also worried about having sufficient access to appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Most relevant to this column, the caregiver was unable to access his primary source of support for his sobriety—attendance at 12-step meetings. Social distancing, which is one of the only proven means we have of reducing transmission of the virus, has had unintended consequences. Although many have found virtual connections rewarding, this nurse needed the curtailed face-to-face contact. The courage that had led him to volunteer for hazardous duty unwontedly resulted in his estrangement: Friends feared that he would expose them to the virus, and he worried that he would expose his family to danger. As in the 1918 flu pandemic, the humans we depend on for reality testing and companionship have been cruelly transformed into potential vectors of the virus.3

Isolation is the worst of all possible counselors as the great Spanish philosopher of alienation Miguel de Unamuno has argued. The deceptive promise of a rapid deliverance from anxiety and pain that substances of abuse proffer apparently led the nurse back to opioids. The virtue of being clean permitted the dirty drug to take advantage of the nurses’ reduced physiologic tolerance to opioids. It is suspected but not confirmed that he fatally overdosed alone in his car.

This Florida nurse is an especially tragic example of a terrible phenomenon being repeated all over the country. And the epidemic of substance use disorders (SUDs) related to COVID-19 is not confined to the US; there are similar reports from other afflicted nations, making addiction truly the other pandemic.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 13.3% of American adults have started or increased their substance use as a means of managing the negative emotions associated with the pandemic.5 Also from March to May 2020, researchers in Baltimore found a 17.6% increase in suspected overdoses in counties advising social distancing and/or mandating stay at home orders.5

These data reinforce a well-known maxim in the addiction community that “addiction is a disease of isolation.”6-8 The burden of the lockdown falls harder on many of the patients we treat in the federal health care system whose other mental and physical health conditions, including chronic pain, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder already placed them at elevated risk of SUDs.9 Director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse Nora Volkow, MD, recently traced the well-known arc from isolation to increased use of drugs and alcohol.10 Isolation is stressful and amplifies negative thoughts, dysphoria, and fearful emotions, which are recognized triggers for the use of substances of abuse. The usually available means of coping with craving, and in many cases withdrawal, such as prescribed medications, visits to therapists, participation in support groups are either not available or much more difficult to access.10 Nor are those without a current or even historical SUD immune to the psychosocial pressures of the pandemic: Isolation also constitutes a risk for the development of de novo addiction particularly among already marginalized groups, such as the elderly and disabled.

The federal government has initiated several important measures to reduce the adverse impact of isolation on persons with SUDs. The Drug Enforcement Administration is exempting qualified practitioners of medication-assisted treatment from the in-person evaluation that is usually required for the prescription of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. This exemption applies to both established patient prescriptions for buprenorphine and new buprenorphine patient prescriptions.11 These and other administrative contingencies at the federal government level can assist persons with OUD to continue to receive medicationassisted treatment.

As individual clinicians in federal practice, we alone cannot engineer such major policy accommodations in response to COVID-19, yet we can still make a difference in the lives of our patients. We can focus a few minutes of our telehealth interactions on checking in with patients who have a history or a current SUD. We can remember to use evidence-based screens for these patients and those with other risk factors to detect drug or alcohol use before it becomes a disorder. And we can identify and refer not only patients but also our beleaguered colleagues who feel alone at sea—to the many lifelines our agencies have cast into what other commentators have referred to as a Perfect Storm of COVID-19 and the opioid crisis (Table).12

1. Borter G. A nurse struggled with COVID-19 trauma. He was found dead in his car. Reuters. May 20, 2020. https:// www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-nurse -death-insigh/a-nurse-struggled-with-covid-19-trauma-he -was-found-dead-in-his-car-idUSKBN22W1JD Accessed September 15, 2020.

2. Geppert CMA. The duty to care and its exceptions in a pandemic. Fed Pract. 2020;37(5):210-211.

3. Kim NY. How the 1918 pandemic frayed social bonds. The Atlantic. March 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com /family/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-loneliness-and-mistrust -1918-flu-pandemic-quarantine/609163. Accessed September 18, 2020.

4. Jemberie WB, Stewart Williams J, Eriksson M, et al. Substance use disorders and COVID-19: multi-faceted problems which require multi-pronged solutions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:714. Published 2020 Jul 21. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714

5. Alter A, Yeager C. COVID-19 impact on US national overdose crises. http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020 /ODMAP-Report-June-2020.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed September 18, 2020.

6. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. Published 2020 Aug 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

7. Grinspoon P. A tale of two epidemics: when COVID-19 and opioid addiction collide. https://www.health.harvard.edu /blog/a-tale-of-two-epidemics-when-covid-19-and-opioid -addiction-collide-2020042019569. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020

8. Bebinger M. Addiction is “a disease of isolation”—so pandemic puts recovery at risk. https://khn.org/news/addiction -is-a-disease-of-isolation-so-pandemic-puts-recovery-at-risk. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020.

9. National Institute of Drug Abuse. Substance abuse and military life. DrugFacts. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications /drugfacts/substance-use-military-life. Published October 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020.

10. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62. doi:10.7326/M20-1212

11. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. FAQS: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. https:// www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing -and-dispensing.pdf. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2020.

12. Spagnolo PA, Montemitro C, Leggio L. New challenges in addiction medicine: COVID-19 infection in patients with alcohol and substance usedisorders-the perfect storm. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):805-807. doi:10.1176/appi. ajp.2020.20040417

1. Borter G. A nurse struggled with COVID-19 trauma. He was found dead in his car. Reuters. May 20, 2020. https:// www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-nurse -death-insigh/a-nurse-struggled-with-covid-19-trauma-he -was-found-dead-in-his-car-idUSKBN22W1JD Accessed September 15, 2020.

2. Geppert CMA. The duty to care and its exceptions in a pandemic. Fed Pract. 2020;37(5):210-211.

3. Kim NY. How the 1918 pandemic frayed social bonds. The Atlantic. March 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com /family/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-loneliness-and-mistrust -1918-flu-pandemic-quarantine/609163. Accessed September 18, 2020.

4. Jemberie WB, Stewart Williams J, Eriksson M, et al. Substance use disorders and COVID-19: multi-faceted problems which require multi-pronged solutions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:714. Published 2020 Jul 21. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00714

5. Alter A, Yeager C. COVID-19 impact on US national overdose crises. http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/news/2020 /ODMAP-Report-June-2020.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed September 18, 2020.

6. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. Published 2020 Aug 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

7. Grinspoon P. A tale of two epidemics: when COVID-19 and opioid addiction collide. https://www.health.harvard.edu /blog/a-tale-of-two-epidemics-when-covid-19-and-opioid -addiction-collide-2020042019569. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020

8. Bebinger M. Addiction is “a disease of isolation”—so pandemic puts recovery at risk. https://khn.org/news/addiction -is-a-disease-of-isolation-so-pandemic-puts-recovery-at-risk. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020.

9. National Institute of Drug Abuse. Substance abuse and military life. DrugFacts. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications /drugfacts/substance-use-military-life. Published October 2019. Accessed September 16, 2020.

10. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62. doi:10.7326/M20-1212

11. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. FAQS: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. https:// www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing -and-dispensing.pdf. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2020.

12. Spagnolo PA, Montemitro C, Leggio L. New challenges in addiction medicine: COVID-19 infection in patients with alcohol and substance usedisorders-the perfect storm. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):805-807. doi:10.1176/appi. ajp.2020.20040417