User login

An eclamptic convulsion is frightening to behold. First, the woman’s face becomes distorted, and her eyes protrude. Then her face acquires a congested expression, and foam may exude from her mouth. Breathing stops.

Because eclampsia is so frightening, the natural tendency is to try to stop a convulsion, but this is not the wisest strategy.

Rather, the foremost priorities are to avoid maternal injury and support cardiovascular functions. How to do this, and how to prevent further convulsions, monitor and deliver the fetus, and avert complications are the focus of this article.

Since eclampsia may be fatal for both mother and fetus, all labor and delivery units and all obstetricians should be prepared to diagnose and manage this grave threat. However, few obstetric units encounter more than 1 or 2 cases a year; most obstetricians have little or no experience managing acute eclampsia. In the Western world, it affects only 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,448 pregnancies.1-4

How a convulsion happens

Most convulsions occur in 2 phases and last for 60 to 75 seconds. The first phase, lasting 15 to 20 seconds, begins with facial twitching, soon followed by a rigid body with generalized muscular contractions.

In the second phase, which lasts about a minute, the muscles of the body alternately contract and relax in rapid succession. This phase begins with the muscles of the jaw and rapidly encompasses eyelids, other facial muscles, and body. If the tongue is unprotected, the woman often bites it.

Coma sometimes follows the convulsion, and deep, rapid breathing usually begins as soon as the convulsion stops. In fact, maintaining oxygenation typically is not a problem after a single convulsion, and the risk of aspiration is low in a well managed patient.

Upon reviving, the woman typically remembers nothing about the seizure.

If convulsions recur, some degree of consciousness returns after each one, although the woman may become combative, agitated, and difficult to control.

Harbingers of complications

In the developed world, eclampsia increases the risk of maternal death (range: 0 to 1.8%).1-5 A recent review of all reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States from 1979 to 1992 found 4,024 cases.6 Of these, 790 (19.6%) were due to preeclampsia-eclampsia, 49% of which were caused by eclampsia. The risk of death from preeclampsia or eclampsia was higher for the following groups:

- women over 30,

- no prenatal care,

- African Americans, and

- onset of preeclampsia or eclampsia before 28 weeks.6

Maternal morbidity

Pregnancies complicated by eclampsia also have higher rates of maternal morbidity such as pulmonary edema and HELLP syndrome (TABLE 1). Complications are substantially higher among women who develop antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term.1-3

TABLE 1

Maternal complications

Antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term, is much more likely to lead to complications

| COMPLICATION | RATE (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 0.5-–2 | Risk of death is higher:

|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | <1 | Usually related to several risk factors |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 2–3 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Disseminated coagulopathy | 3–5 | Regional anesthesia is contraindicated in these patients, and there is a heightened risk of hemorrhagic shock |

| Pulmonary edema | 3–5 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Acute renal failure | 5–9 | Usually seen in association with abruptio placentae, maternal hemorrhage, and prolonged maternal hypotension |

| Abruptio placentae | 7–10 | Can occur after a convulsion; suspect it if fetal bradycardia or late decelerations persist |

| HELLP syndrome | 10–15 |

Adverse perinatal outcomes

Perinatal mortality and morbidity are high in eclampsia, with a perinatal death rate in recent series of 5.6% to 11.8%.1,7 This high rate is related to prematurity, abruptio placentae, and severe growth restriction.1

Preterm deliveries occur in approximately 50% of cases, and about 25% occur before 32 weeks’ gestation.1

Diagnosis can be tricky

When the patient has generalized edema, hypertension, proteinuria, and convulsions, diagnosis of eclampsia is straightforward. Unfortunately, women with eclampsia exhibit a broad spectrum of signs, ranging from severe hypertension, severe proteinuria, and generalized edema, to absent or minimal hypertension, nonexistent proteinuria, and no edema (TABLE 2).1

Hypertension is the hallmark of diagnosis. Hypertension is severe (at least 160 mm Hg systolic and/or at least 110 mm Hg diastolic) in 20% to 54% of cases, and it is mild (systolic pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg) in 30% to 60% of cases.2,3 In 16% of cases, there may be no hypertension at all.2

Proteinuria. Eclampsia usually is associated with proteinuria (at least 1+ on dipstick).1 However, when I studied a series of 399 women with eclampsia, I found substantial proteinuria (3+ or above on dipstick) in only 48% of cases; proteinuria was absent in 14%.2

Edema. A weight gain of more than 2 lb per week (with or without clinical edema) during the third trimester may be the first sign of eclampsia. However, in my series of 399 women, edema was absent in 26% of cases.2

TABLE 2

Signs and symptoms of eclampsia*

Hypertension and proteinuria in eclampsia may be severe, mild, or even absent

| CONDITION | FREQUENCY (%) IN WOMEN WITH ECLAMPSIA | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| SIGNS | ||

| Hypertension | 85 | Should be documented on at least 2 occasions more than 6 hours apart |

| Severe: 160/110 mm Hg or more | 20–54 | |

| Mild: 140–160/90–110 mm Hg | 30–60 | |

| No hypertension2 | 16 | |

| Proteinuria | 85 | |

| At least 1+ on dipstick2 | 48 | |

| At least 3+ on dipstick | 14 | |

| No proteinuria | 15 | |

| SYMPTOMS | ||

| At least 1 of the following: | 33–75 | Clinical symptoms may occur before or after a convulsion |

| Headache | 30–70 | Persistent, occipital, or frontal |

| Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain | 12–20 | |

| Visual changes | 19–32 | Blurred vision, photophobia |

| Altered mental changes | 4–5 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Symptoms of eclampsia

Several clinical symptoms can occur before or after a convulsion1:

- persistent occipital or frontal headaches,

- blurred vision,

- photophobia,

- epigastric and/or right upper quadrant pain, and

- altered mental status.

Usual times of onset

Eclamptic convulsions can occur during pregnancy or delivery, or after delivery ( TABLE 3).1-5

Approximately 91% of antepartum cases develop at 28 weeks or beyond. The remaining cases tend to occur between 21 and 27 weeks’ gestation (7.5%), or at or before 20 weeks (1.5%).2

When eclampsia occurs before 20 weeks, it usually involves molar or hydropic degeneration of the placenta, with or without a fetus.1 However, eclampsia can occur in the first half of pregnancy without molar degeneration of the placenta, although this is rare.1,2 These women are sometimes misdiagnosed as having hypertensive encephalopathy, seizure disorder, or thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. Thus, women who develop convulsions in association with hypertension and proteinuria in the first half of pregnancy should be assumed to have eclampsia until proven otherwise,1 and require ultrasound examination of the uterus to rule out molar pregnancy and/or hydropic or cystic degeneration of the placenta.

Postpartum cases tend to occur within the first 48 hours, although some develop beyond this limit and have been reported as late as 23 days postpartum.8

Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery.8 These women have signs and symptoms consistent with preeclampsia along with their convulsions.8,9 Thus, women who develop convulsions with hypertension and/or proteinuria, or with headaches or blurred vision, after 48 hours postpartum should be assumed to have eclampsia and treated accordingly.8,9

When eclampsia occurs especially late, perform an extensive neurologic examination to rule out other cerebral pathology.1,10

Eclampsia is atypical if convulsions occur before 20 weeks’ gestation or beyond 48 hours postpartum. It also is atypical if convulsions develop or persist despite adequate magnesium sulfate, or if the patient develops focal neurologic deficits, disorientation, blindness, or coma. In these cases, conduct a neurologic exam and cerebral imaging to exclude neurologic pathology.8-10

TABLE 3

Usual times of onset*

91% of antepartum eclampsia cases occur at 28 weeks or later, although eclamptic convulsions can occur at any time during pregnancy or delivery, or postpartum

| ONSET | FREQUENCY (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Antepartum | 38–53 | Maternal and perinatal mortality, and the incidence of complications and underlying disease, are higher in antepartum eclampsia, especially in early cases |

| ≤20 weeks | 1.5 | |

| 21 to 27 weeks | 7.5 | |

| ≥28 weeks | 91 | |

| Intrapartum | 18–36 | Intrapartum eclampsia more closely resembles postpartum disease than antepartum cases |

| Postpartum | 11–44 | Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery |

| ≤48 hours | 7–39 | |

| >48 hours | 5–26 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Differential diagnosis

As with other aspects of preeclampsia, the presenting symptoms, clinical findings, and many laboratory results in eclampsia overlap several other medical and surgical conditions.1,10 Of course, eclampsia is the most common cause of convulsions in a woman with hypertension and/or proteinuria during pregnancy or immediately postpartum. On rare occasions, other causes of convulsions in pregnancy or postpartum may mimic eclampsia.1 These potential diagnoses are particularly important when the woman has focal neurologic deficits, prolonged coma, or atypical eclampsia.

The differential diagnosis encompasses a variety of cerebrovascular and metabolic disorders:

- hemorrhage,

- ruptured aneurysm or malformation,

- arterial embolism, thrombosis,

- venous thrombosis,

- hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy,

- angiomas,

- hypertensive encephalopathy,

- seizure disorder,

- hypoglycemia, hyponatremia,

- posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome,

- thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura,

- postdural puncture syndrome, and

- cerebral vasculitis/angiopathy.

Other diseases may factor in

Some women develop gestational hypertension or preeclampsia in association with connective tissue disease, thrombophilias, seizure disorder, or hypertensive encephalopathy, further confounding the diagnosis.

Thus, make every effort to ensure a correct diagnosis, since management may differ among these conditions.

Managing convulsions

Do not try to stop the first convulsion

The natural tendency is to try and interrupt the convulsion, but this is not recommended. Nor should you give a drug such as diazepam to shorten or stop the convulsion, especially if the patient lacks an intravenous line and no one skilled in intubation is immediately available. If diazepam is given, do not exceed 5 mg over 60 seconds. Rapid administration of this drug may lead to apnea or cardiac arrest, or both.

Steps to prevent maternal injury

During or immediately after the acute convulsive episode, take steps to prevent serious maternal injury and aspiration, assess and establish airway patency, and ensure maternal oxygenation (TABLE 4).

Elevate and pad the bed’s side rails and insert a padded tongue blade between the patient’s teeth, taking care not to trigger the gag reflex.

Physical restraints also may be needed.

Prevent aspiration. To minimize the risk of aspiration, place the patient in the lateral decubitus position, and suction vomitus and oral secretions as needed. Be aware that aspiration can occur when the padded tongue blade is forced to the back of the throat, stimulating the gag reflex and resultant vomiting.

TABLE 4

During a convulsion, 3 spheres of concern

| AVOID MATERNAL INJURY |

| Insert padded tongue blade |

| Avoid inducing gag reflex |

| Elevate padded bedside rails |

| Use physical restraints as needed |

| MAINTAIN OXYGENATION TO MOTHER AND FETUS |

| Apply face mask with or without oxygen reservoir at 8–10 L/minute |

| Monitor oxygenation and metabolic status via |

| Transcutaneous pulse oximetry |

| Arterial blood gases (sodium bicarbonate administered accordingly) |

| Correct oxygenation and metabolic status before administering anesthetics that may depress myocardial function |

| MINIMIZE ASPIRATION |

| Place patient in lateral decubitus position (which also maximizes uterine blood flow and venous return) |

| Suction vomitus and oral secretions |

| Obtain chest x-ray after the convulsion is controlled to rule out aspiration |

Tips on supplemental oxygenation

Although the initial seizure lasts only a minute or 2, it is important to maintain oxygenation by giving supplemental oxygen via a face mask, with or without an oxygen reservoir, at 8 to 10 L per minute. This is important because hypoventilation and respiratory acidosis often occur.

Once the convulsion ends and the patient resumes breathing, oxygenation is rarely a problem. However, maternal hypoxemia and acidosis can develop in women with repetitive convulsions, aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or a combination of these factors. Thus, transcutaneous pulse oximetry is advisable to monitor oxygenation in eclamptic patients.

Arterial blood gas analysis is necessary if pulse oximetry shows abnormal oxygen saturation (ie, at or below 92%).

Strategy to prevent recurrence

Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice to treat and prevent subsequent convulsions in women with eclampsia.1,2

Dosage. I give a loading dose of 6 g over 15 to 20 minutes, followed by a maintenance dose of 2 g per hour as a continuous intravenous solution.

Approximately 10% of eclamptic women have a second convulsion after receiving magnesium sulfate.1,2 When this occurs, I give another 2-g bolus intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

More rarely, a woman will continue to have convulsions while receiving adequate and therapeutic doses of magnesium sulfate.

I treat such patients with sodium amobarbital, 250 mg, intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

Monitor maternal magnesium levels

Plasma levels should be in the range of 4 to 8 mg/dL during treatment for eclampsia, and are determined by the volume of distribution and by renal excretion. Thus, it is important to monitor the patient for magnesium toxicity, particularly if she has renal dysfunction (serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or above) or urine output below 100 mL in 4 hours. In these women, adjust the maintenance dose according to plasma levels.

Side effects of magnesium including flushing, a feeling of warmth, nausea and vomiting, double vision, and slurred speech (TABLE 5).

If magnesium toxicity is suspected, immediately discontinue the infusion and administer supplemental oxygen along with 10 mL of 10% calcium gluconate (1 g total) as an intravenous push slowly over 5 minutes.

If respiratory arrest occurs, prompt resuscitation—including intubation and assisted ventilation—is vital.

TABLE 5

Clinical manifestations of magnesium toxicity

Maternal plasma levels of 4 to 8 mg/dL are appropriate during treatment for eclampsia; higher levels signal toxicity

| IF THE MAGNESIUM LEVEL IS… | THE CLINICAL MANIFESTATION IS… |

|---|---|

| 8–12 mg/dL | Loss of patellar reflex |

| Double or blurred vision | |

| Headache and nausea | |

| 9–12 mg/dL | Feeling of warmth, flushing |

| 10–12 mg/dL | Somnolence |

| Slurred speech | |

| 15–17 mg/dL | Muscular paralysis |

| Respiratory arrest | |

| 30–35 mg/dL | Cardiac arrest |

Controlling severe hypertension

The next step is to reduce blood pressure to a safe range. The objective: to preserve cerebral autoregulation and prevent congestive heart failure without compromising cerebral perfusion or jeopardizing uteroplacental blood flow, which is already reduced in many women with eclampsia.1

To these ends, try to keep systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg and diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg. This can be achieved with:

- bolus 5- to 10-mg doses of hydralazine,

- 20 to 40 mg labetalol intravenously every 15 minutes, as needed, or

- 10 to 20 mg oral nifedipine every 30 minutes.

Other potent antihypertensive drugs such as sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerine are rarely needed in eclampsia, and diuretics are indicated only in the presence of pulmonary edema.

Intrapartum management

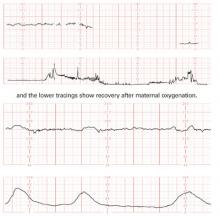

Maternal hypoxemia and hypercarbia cause fetal heart rate and uterine activity changes during and immediately following a convulsion.

Fetal heart rate changes

These can include bradycardia, transient late decelerations, decreased beat-to-beat variability, and compensatory tachycardia.

The interval from onset of the seizure to the fall in fetal heart rate is approximately 5 minutes (FIGURE 1). Transitory fetal tachycardia frequently occurs after the prolonged bradycardia. The loss of beat-to-beat variability, with transitory late decelerations, occurs during the recovery phase.

The mechanism for the transient fetal bradycardia may be intense vasospasm and uterine hyperactivity, which may decrease uterine blood flow. The absence of maternal respiration during the convulsion may also contribute to fetal heart rate changes.

Since the fetal heart rate usually returns to normal after a convulsion, other conditions should be considered if an abnormal pattern persists.

In some cases, it may take longer for the heart rate pattern to return to baseline if the fetus is preterm with growth restriction.

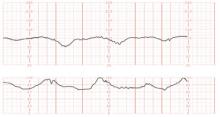

Placental abruption may occur after the convulsion and should be suspected if fetal bradycardia or repetitive late decelerations persist (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1 Fetal response to a convulsion The top 2 tracings show fetal bradycardia during an eclamptic convulsion

FIGURE 2 Abruptio placentae Repetitive late decelerations secondary to abruptio placentae, necessitating cesarean section

Uterine activity

During a convulsion, contractions can increase in frequency and tone. The duration of increased uterine activity varies from 2 to 14 minutes.

These changes usually resolve spontaneously within 3 to 10 minutes following the termination of convulsions and correction of maternal hypoxemia (FIGURE 1).

If uterine hyperactivity persists, suspect placental abruption (FIGURE 2).

Do not rush to cesarean

It benefits the fetus to allow in utero recovery from the maternal convulsion, hypoxia, and hypercarbia before delivery. However, if the bradycardia and/or recurrent late decelerations persist beyond 10 to 15 minutes despite all efforts, suspect abruptio placentae or nonreassuring fetal status.

Once the patient regains consciousness and is oriented to name, place, and time, and her convulsions are controlled and condition stabilized, proceed with delivery.

Choosing a delivery route

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean. The decision to perform a cesarean should be based on fetal gestational age, fetal condition, presence of labor, and cervical Bishop score. I recommend:

- Cesarean section for women with eclampsia before 30 weeks’ gestation who are not in labor and whose Bishop score is below 5.

- Vaginal delivery for women in labor or with rupture of membranes, provided there are no obstetric complications.

- Labor induction with oxytocin infusion or prostaglandins in all women at or after 30 weeks, regardless of the Bishop score, and in women before 30 weeks when the Bishop score is 5 or above.

Maternal pain relief

During labor and delivery, systemic opioids or epidural anesthesia can provide pain relief—the same recommendations as for women with severe preeclampsia.

For cesarean delivery, an epidural, spinal, or combined techniques of regional anesthesia are suitable.

Do not use regional anesthesia if there is coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50,000/mm3). In women with eclampsia, general anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration and failed intubation due to airway edema, and is associated with marked increases in systemic and cerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Women with airway or laryngeal edema may require awake intubation under fiber optic observation, with tracheostomy immediately available.

Changes in systemic or cerebral pressures may be attenuated by pretreatment with labetalol or nitroglycerine injections.

Postpartum management

After delivery, women with eclampsia require close monitoring of vital signs, fluid intake and output, and symptoms for at least 48 hours.

Risk of pulmonary edema

These women usually receive large amounts of intravenous fluids during labor, delivery, and postpartum. In addition, during the postpartum period, extracellular fluid mobilizes, leading to increased intravascular volume.

As a result, women who develop eclampsia—particularly those with abnormal renal function, abruptio placentae, and/or preexisting chronic hypertension— face an increased risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension.2

Frequent evaluation of the amount of intravenous fluids is necessary, as well as oral intake, blood products, and urine output. They also need pulse oximetry and pulmonary auscultation.

Continue magnesium sulfate

Parenteral magnesium sulfate should be given for at least 24 hours after delivery and/or for at least 24 hours after the last convulsion.

If the patient has oliguria (less than 100 mL over 4 hours), both fluid administration and the dose of magnesium sulfate should be reduced.

Oral antihypertensives

Other oral antihypertensive agents such as labetalol or nifedipine can be given to keep systolic blood pressure below 155 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. Nifedipine offers the benefit of improved diuresis in the postpartum period.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Sibai BM. Diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:402-410.

2. Mattar F, Sibai BM. Eclampsia VIII. Risk factors for maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:307-312.

3. Douglas KA, Redman CW. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1994;309:1395-1400.

4. Rugard O, Carling MS, Berg G. Eclampsia at a tertiary hospital, 1973–99. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:240-245.

5. Katz VL, Farmer R, Kuller J. Preeclampsia into eclampsia: toward a new paradigm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1389-1396.

6. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:533-538.

7. Leitch CR, Cameron AD, Walker JJ. The changing pattern of eclampsia over a 60-year period. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:917-922.

8. Lubarsky SL, Barton JR, Friedman SA, Nasreddine S, Ramaddan MK, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia revisited. Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;83:502-505.

9. Chames MC, Livingston JC, Ivester TS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia: a preventable disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1174-1177.

10. Witlin AG, Friedman SA, Egerman RS, Frangieh AY, Sibai BM. Cerebrovascular disorders complicating pregnancy. Beyond eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:139-148.

An eclamptic convulsion is frightening to behold. First, the woman’s face becomes distorted, and her eyes protrude. Then her face acquires a congested expression, and foam may exude from her mouth. Breathing stops.

Because eclampsia is so frightening, the natural tendency is to try to stop a convulsion, but this is not the wisest strategy.

Rather, the foremost priorities are to avoid maternal injury and support cardiovascular functions. How to do this, and how to prevent further convulsions, monitor and deliver the fetus, and avert complications are the focus of this article.

Since eclampsia may be fatal for both mother and fetus, all labor and delivery units and all obstetricians should be prepared to diagnose and manage this grave threat. However, few obstetric units encounter more than 1 or 2 cases a year; most obstetricians have little or no experience managing acute eclampsia. In the Western world, it affects only 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,448 pregnancies.1-4

How a convulsion happens

Most convulsions occur in 2 phases and last for 60 to 75 seconds. The first phase, lasting 15 to 20 seconds, begins with facial twitching, soon followed by a rigid body with generalized muscular contractions.

In the second phase, which lasts about a minute, the muscles of the body alternately contract and relax in rapid succession. This phase begins with the muscles of the jaw and rapidly encompasses eyelids, other facial muscles, and body. If the tongue is unprotected, the woman often bites it.

Coma sometimes follows the convulsion, and deep, rapid breathing usually begins as soon as the convulsion stops. In fact, maintaining oxygenation typically is not a problem after a single convulsion, and the risk of aspiration is low in a well managed patient.

Upon reviving, the woman typically remembers nothing about the seizure.

If convulsions recur, some degree of consciousness returns after each one, although the woman may become combative, agitated, and difficult to control.

Harbingers of complications

In the developed world, eclampsia increases the risk of maternal death (range: 0 to 1.8%).1-5 A recent review of all reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States from 1979 to 1992 found 4,024 cases.6 Of these, 790 (19.6%) were due to preeclampsia-eclampsia, 49% of which were caused by eclampsia. The risk of death from preeclampsia or eclampsia was higher for the following groups:

- women over 30,

- no prenatal care,

- African Americans, and

- onset of preeclampsia or eclampsia before 28 weeks.6

Maternal morbidity

Pregnancies complicated by eclampsia also have higher rates of maternal morbidity such as pulmonary edema and HELLP syndrome (TABLE 1). Complications are substantially higher among women who develop antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term.1-3

TABLE 1

Maternal complications

Antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term, is much more likely to lead to complications

| COMPLICATION | RATE (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 0.5-–2 | Risk of death is higher:

|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | <1 | Usually related to several risk factors |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 2–3 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Disseminated coagulopathy | 3–5 | Regional anesthesia is contraindicated in these patients, and there is a heightened risk of hemorrhagic shock |

| Pulmonary edema | 3–5 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Acute renal failure | 5–9 | Usually seen in association with abruptio placentae, maternal hemorrhage, and prolonged maternal hypotension |

| Abruptio placentae | 7–10 | Can occur after a convulsion; suspect it if fetal bradycardia or late decelerations persist |

| HELLP syndrome | 10–15 |

Adverse perinatal outcomes

Perinatal mortality and morbidity are high in eclampsia, with a perinatal death rate in recent series of 5.6% to 11.8%.1,7 This high rate is related to prematurity, abruptio placentae, and severe growth restriction.1

Preterm deliveries occur in approximately 50% of cases, and about 25% occur before 32 weeks’ gestation.1

Diagnosis can be tricky

When the patient has generalized edema, hypertension, proteinuria, and convulsions, diagnosis of eclampsia is straightforward. Unfortunately, women with eclampsia exhibit a broad spectrum of signs, ranging from severe hypertension, severe proteinuria, and generalized edema, to absent or minimal hypertension, nonexistent proteinuria, and no edema (TABLE 2).1

Hypertension is the hallmark of diagnosis. Hypertension is severe (at least 160 mm Hg systolic and/or at least 110 mm Hg diastolic) in 20% to 54% of cases, and it is mild (systolic pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg) in 30% to 60% of cases.2,3 In 16% of cases, there may be no hypertension at all.2

Proteinuria. Eclampsia usually is associated with proteinuria (at least 1+ on dipstick).1 However, when I studied a series of 399 women with eclampsia, I found substantial proteinuria (3+ or above on dipstick) in only 48% of cases; proteinuria was absent in 14%.2

Edema. A weight gain of more than 2 lb per week (with or without clinical edema) during the third trimester may be the first sign of eclampsia. However, in my series of 399 women, edema was absent in 26% of cases.2

TABLE 2

Signs and symptoms of eclampsia*

Hypertension and proteinuria in eclampsia may be severe, mild, or even absent

| CONDITION | FREQUENCY (%) IN WOMEN WITH ECLAMPSIA | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| SIGNS | ||

| Hypertension | 85 | Should be documented on at least 2 occasions more than 6 hours apart |

| Severe: 160/110 mm Hg or more | 20–54 | |

| Mild: 140–160/90–110 mm Hg | 30–60 | |

| No hypertension2 | 16 | |

| Proteinuria | 85 | |

| At least 1+ on dipstick2 | 48 | |

| At least 3+ on dipstick | 14 | |

| No proteinuria | 15 | |

| SYMPTOMS | ||

| At least 1 of the following: | 33–75 | Clinical symptoms may occur before or after a convulsion |

| Headache | 30–70 | Persistent, occipital, or frontal |

| Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain | 12–20 | |

| Visual changes | 19–32 | Blurred vision, photophobia |

| Altered mental changes | 4–5 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Symptoms of eclampsia

Several clinical symptoms can occur before or after a convulsion1:

- persistent occipital or frontal headaches,

- blurred vision,

- photophobia,

- epigastric and/or right upper quadrant pain, and

- altered mental status.

Usual times of onset

Eclamptic convulsions can occur during pregnancy or delivery, or after delivery ( TABLE 3).1-5

Approximately 91% of antepartum cases develop at 28 weeks or beyond. The remaining cases tend to occur between 21 and 27 weeks’ gestation (7.5%), or at or before 20 weeks (1.5%).2

When eclampsia occurs before 20 weeks, it usually involves molar or hydropic degeneration of the placenta, with or without a fetus.1 However, eclampsia can occur in the first half of pregnancy without molar degeneration of the placenta, although this is rare.1,2 These women are sometimes misdiagnosed as having hypertensive encephalopathy, seizure disorder, or thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. Thus, women who develop convulsions in association with hypertension and proteinuria in the first half of pregnancy should be assumed to have eclampsia until proven otherwise,1 and require ultrasound examination of the uterus to rule out molar pregnancy and/or hydropic or cystic degeneration of the placenta.

Postpartum cases tend to occur within the first 48 hours, although some develop beyond this limit and have been reported as late as 23 days postpartum.8

Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery.8 These women have signs and symptoms consistent with preeclampsia along with their convulsions.8,9 Thus, women who develop convulsions with hypertension and/or proteinuria, or with headaches or blurred vision, after 48 hours postpartum should be assumed to have eclampsia and treated accordingly.8,9

When eclampsia occurs especially late, perform an extensive neurologic examination to rule out other cerebral pathology.1,10

Eclampsia is atypical if convulsions occur before 20 weeks’ gestation or beyond 48 hours postpartum. It also is atypical if convulsions develop or persist despite adequate magnesium sulfate, or if the patient develops focal neurologic deficits, disorientation, blindness, or coma. In these cases, conduct a neurologic exam and cerebral imaging to exclude neurologic pathology.8-10

TABLE 3

Usual times of onset*

91% of antepartum eclampsia cases occur at 28 weeks or later, although eclamptic convulsions can occur at any time during pregnancy or delivery, or postpartum

| ONSET | FREQUENCY (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Antepartum | 38–53 | Maternal and perinatal mortality, and the incidence of complications and underlying disease, are higher in antepartum eclampsia, especially in early cases |

| ≤20 weeks | 1.5 | |

| 21 to 27 weeks | 7.5 | |

| ≥28 weeks | 91 | |

| Intrapartum | 18–36 | Intrapartum eclampsia more closely resembles postpartum disease than antepartum cases |

| Postpartum | 11–44 | Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery |

| ≤48 hours | 7–39 | |

| >48 hours | 5–26 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Differential diagnosis

As with other aspects of preeclampsia, the presenting symptoms, clinical findings, and many laboratory results in eclampsia overlap several other medical and surgical conditions.1,10 Of course, eclampsia is the most common cause of convulsions in a woman with hypertension and/or proteinuria during pregnancy or immediately postpartum. On rare occasions, other causes of convulsions in pregnancy or postpartum may mimic eclampsia.1 These potential diagnoses are particularly important when the woman has focal neurologic deficits, prolonged coma, or atypical eclampsia.

The differential diagnosis encompasses a variety of cerebrovascular and metabolic disorders:

- hemorrhage,

- ruptured aneurysm or malformation,

- arterial embolism, thrombosis,

- venous thrombosis,

- hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy,

- angiomas,

- hypertensive encephalopathy,

- seizure disorder,

- hypoglycemia, hyponatremia,

- posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome,

- thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura,

- postdural puncture syndrome, and

- cerebral vasculitis/angiopathy.

Other diseases may factor in

Some women develop gestational hypertension or preeclampsia in association with connective tissue disease, thrombophilias, seizure disorder, or hypertensive encephalopathy, further confounding the diagnosis.

Thus, make every effort to ensure a correct diagnosis, since management may differ among these conditions.

Managing convulsions

Do not try to stop the first convulsion

The natural tendency is to try and interrupt the convulsion, but this is not recommended. Nor should you give a drug such as diazepam to shorten or stop the convulsion, especially if the patient lacks an intravenous line and no one skilled in intubation is immediately available. If diazepam is given, do not exceed 5 mg over 60 seconds. Rapid administration of this drug may lead to apnea or cardiac arrest, or both.

Steps to prevent maternal injury

During or immediately after the acute convulsive episode, take steps to prevent serious maternal injury and aspiration, assess and establish airway patency, and ensure maternal oxygenation (TABLE 4).

Elevate and pad the bed’s side rails and insert a padded tongue blade between the patient’s teeth, taking care not to trigger the gag reflex.

Physical restraints also may be needed.

Prevent aspiration. To minimize the risk of aspiration, place the patient in the lateral decubitus position, and suction vomitus and oral secretions as needed. Be aware that aspiration can occur when the padded tongue blade is forced to the back of the throat, stimulating the gag reflex and resultant vomiting.

TABLE 4

During a convulsion, 3 spheres of concern

| AVOID MATERNAL INJURY |

| Insert padded tongue blade |

| Avoid inducing gag reflex |

| Elevate padded bedside rails |

| Use physical restraints as needed |

| MAINTAIN OXYGENATION TO MOTHER AND FETUS |

| Apply face mask with or without oxygen reservoir at 8–10 L/minute |

| Monitor oxygenation and metabolic status via |

| Transcutaneous pulse oximetry |

| Arterial blood gases (sodium bicarbonate administered accordingly) |

| Correct oxygenation and metabolic status before administering anesthetics that may depress myocardial function |

| MINIMIZE ASPIRATION |

| Place patient in lateral decubitus position (which also maximizes uterine blood flow and venous return) |

| Suction vomitus and oral secretions |

| Obtain chest x-ray after the convulsion is controlled to rule out aspiration |

Tips on supplemental oxygenation

Although the initial seizure lasts only a minute or 2, it is important to maintain oxygenation by giving supplemental oxygen via a face mask, with or without an oxygen reservoir, at 8 to 10 L per minute. This is important because hypoventilation and respiratory acidosis often occur.

Once the convulsion ends and the patient resumes breathing, oxygenation is rarely a problem. However, maternal hypoxemia and acidosis can develop in women with repetitive convulsions, aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or a combination of these factors. Thus, transcutaneous pulse oximetry is advisable to monitor oxygenation in eclamptic patients.

Arterial blood gas analysis is necessary if pulse oximetry shows abnormal oxygen saturation (ie, at or below 92%).

Strategy to prevent recurrence

Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice to treat and prevent subsequent convulsions in women with eclampsia.1,2

Dosage. I give a loading dose of 6 g over 15 to 20 minutes, followed by a maintenance dose of 2 g per hour as a continuous intravenous solution.

Approximately 10% of eclamptic women have a second convulsion after receiving magnesium sulfate.1,2 When this occurs, I give another 2-g bolus intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

More rarely, a woman will continue to have convulsions while receiving adequate and therapeutic doses of magnesium sulfate.

I treat such patients with sodium amobarbital, 250 mg, intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

Monitor maternal magnesium levels

Plasma levels should be in the range of 4 to 8 mg/dL during treatment for eclampsia, and are determined by the volume of distribution and by renal excretion. Thus, it is important to monitor the patient for magnesium toxicity, particularly if she has renal dysfunction (serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or above) or urine output below 100 mL in 4 hours. In these women, adjust the maintenance dose according to plasma levels.

Side effects of magnesium including flushing, a feeling of warmth, nausea and vomiting, double vision, and slurred speech (TABLE 5).

If magnesium toxicity is suspected, immediately discontinue the infusion and administer supplemental oxygen along with 10 mL of 10% calcium gluconate (1 g total) as an intravenous push slowly over 5 minutes.

If respiratory arrest occurs, prompt resuscitation—including intubation and assisted ventilation—is vital.

TABLE 5

Clinical manifestations of magnesium toxicity

Maternal plasma levels of 4 to 8 mg/dL are appropriate during treatment for eclampsia; higher levels signal toxicity

| IF THE MAGNESIUM LEVEL IS… | THE CLINICAL MANIFESTATION IS… |

|---|---|

| 8–12 mg/dL | Loss of patellar reflex |

| Double or blurred vision | |

| Headache and nausea | |

| 9–12 mg/dL | Feeling of warmth, flushing |

| 10–12 mg/dL | Somnolence |

| Slurred speech | |

| 15–17 mg/dL | Muscular paralysis |

| Respiratory arrest | |

| 30–35 mg/dL | Cardiac arrest |

Controlling severe hypertension

The next step is to reduce blood pressure to a safe range. The objective: to preserve cerebral autoregulation and prevent congestive heart failure without compromising cerebral perfusion or jeopardizing uteroplacental blood flow, which is already reduced in many women with eclampsia.1

To these ends, try to keep systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg and diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg. This can be achieved with:

- bolus 5- to 10-mg doses of hydralazine,

- 20 to 40 mg labetalol intravenously every 15 minutes, as needed, or

- 10 to 20 mg oral nifedipine every 30 minutes.

Other potent antihypertensive drugs such as sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerine are rarely needed in eclampsia, and diuretics are indicated only in the presence of pulmonary edema.

Intrapartum management

Maternal hypoxemia and hypercarbia cause fetal heart rate and uterine activity changes during and immediately following a convulsion.

Fetal heart rate changes

These can include bradycardia, transient late decelerations, decreased beat-to-beat variability, and compensatory tachycardia.

The interval from onset of the seizure to the fall in fetal heart rate is approximately 5 minutes (FIGURE 1). Transitory fetal tachycardia frequently occurs after the prolonged bradycardia. The loss of beat-to-beat variability, with transitory late decelerations, occurs during the recovery phase.

The mechanism for the transient fetal bradycardia may be intense vasospasm and uterine hyperactivity, which may decrease uterine blood flow. The absence of maternal respiration during the convulsion may also contribute to fetal heart rate changes.

Since the fetal heart rate usually returns to normal after a convulsion, other conditions should be considered if an abnormal pattern persists.

In some cases, it may take longer for the heart rate pattern to return to baseline if the fetus is preterm with growth restriction.

Placental abruption may occur after the convulsion and should be suspected if fetal bradycardia or repetitive late decelerations persist (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1 Fetal response to a convulsion The top 2 tracings show fetal bradycardia during an eclamptic convulsion

FIGURE 2 Abruptio placentae Repetitive late decelerations secondary to abruptio placentae, necessitating cesarean section

Uterine activity

During a convulsion, contractions can increase in frequency and tone. The duration of increased uterine activity varies from 2 to 14 minutes.

These changes usually resolve spontaneously within 3 to 10 minutes following the termination of convulsions and correction of maternal hypoxemia (FIGURE 1).

If uterine hyperactivity persists, suspect placental abruption (FIGURE 2).

Do not rush to cesarean

It benefits the fetus to allow in utero recovery from the maternal convulsion, hypoxia, and hypercarbia before delivery. However, if the bradycardia and/or recurrent late decelerations persist beyond 10 to 15 minutes despite all efforts, suspect abruptio placentae or nonreassuring fetal status.

Once the patient regains consciousness and is oriented to name, place, and time, and her convulsions are controlled and condition stabilized, proceed with delivery.

Choosing a delivery route

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean. The decision to perform a cesarean should be based on fetal gestational age, fetal condition, presence of labor, and cervical Bishop score. I recommend:

- Cesarean section for women with eclampsia before 30 weeks’ gestation who are not in labor and whose Bishop score is below 5.

- Vaginal delivery for women in labor or with rupture of membranes, provided there are no obstetric complications.

- Labor induction with oxytocin infusion or prostaglandins in all women at or after 30 weeks, regardless of the Bishop score, and in women before 30 weeks when the Bishop score is 5 or above.

Maternal pain relief

During labor and delivery, systemic opioids or epidural anesthesia can provide pain relief—the same recommendations as for women with severe preeclampsia.

For cesarean delivery, an epidural, spinal, or combined techniques of regional anesthesia are suitable.

Do not use regional anesthesia if there is coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50,000/mm3). In women with eclampsia, general anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration and failed intubation due to airway edema, and is associated with marked increases in systemic and cerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Women with airway or laryngeal edema may require awake intubation under fiber optic observation, with tracheostomy immediately available.

Changes in systemic or cerebral pressures may be attenuated by pretreatment with labetalol or nitroglycerine injections.

Postpartum management

After delivery, women with eclampsia require close monitoring of vital signs, fluid intake and output, and symptoms for at least 48 hours.

Risk of pulmonary edema

These women usually receive large amounts of intravenous fluids during labor, delivery, and postpartum. In addition, during the postpartum period, extracellular fluid mobilizes, leading to increased intravascular volume.

As a result, women who develop eclampsia—particularly those with abnormal renal function, abruptio placentae, and/or preexisting chronic hypertension— face an increased risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension.2

Frequent evaluation of the amount of intravenous fluids is necessary, as well as oral intake, blood products, and urine output. They also need pulse oximetry and pulmonary auscultation.

Continue magnesium sulfate

Parenteral magnesium sulfate should be given for at least 24 hours after delivery and/or for at least 24 hours after the last convulsion.

If the patient has oliguria (less than 100 mL over 4 hours), both fluid administration and the dose of magnesium sulfate should be reduced.

Oral antihypertensives

Other oral antihypertensive agents such as labetalol or nifedipine can be given to keep systolic blood pressure below 155 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. Nifedipine offers the benefit of improved diuresis in the postpartum period.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

An eclamptic convulsion is frightening to behold. First, the woman’s face becomes distorted, and her eyes protrude. Then her face acquires a congested expression, and foam may exude from her mouth. Breathing stops.

Because eclampsia is so frightening, the natural tendency is to try to stop a convulsion, but this is not the wisest strategy.

Rather, the foremost priorities are to avoid maternal injury and support cardiovascular functions. How to do this, and how to prevent further convulsions, monitor and deliver the fetus, and avert complications are the focus of this article.

Since eclampsia may be fatal for both mother and fetus, all labor and delivery units and all obstetricians should be prepared to diagnose and manage this grave threat. However, few obstetric units encounter more than 1 or 2 cases a year; most obstetricians have little or no experience managing acute eclampsia. In the Western world, it affects only 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,448 pregnancies.1-4

How a convulsion happens

Most convulsions occur in 2 phases and last for 60 to 75 seconds. The first phase, lasting 15 to 20 seconds, begins with facial twitching, soon followed by a rigid body with generalized muscular contractions.

In the second phase, which lasts about a minute, the muscles of the body alternately contract and relax in rapid succession. This phase begins with the muscles of the jaw and rapidly encompasses eyelids, other facial muscles, and body. If the tongue is unprotected, the woman often bites it.

Coma sometimes follows the convulsion, and deep, rapid breathing usually begins as soon as the convulsion stops. In fact, maintaining oxygenation typically is not a problem after a single convulsion, and the risk of aspiration is low in a well managed patient.

Upon reviving, the woman typically remembers nothing about the seizure.

If convulsions recur, some degree of consciousness returns after each one, although the woman may become combative, agitated, and difficult to control.

Harbingers of complications

In the developed world, eclampsia increases the risk of maternal death (range: 0 to 1.8%).1-5 A recent review of all reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States from 1979 to 1992 found 4,024 cases.6 Of these, 790 (19.6%) were due to preeclampsia-eclampsia, 49% of which were caused by eclampsia. The risk of death from preeclampsia or eclampsia was higher for the following groups:

- women over 30,

- no prenatal care,

- African Americans, and

- onset of preeclampsia or eclampsia before 28 weeks.6

Maternal morbidity

Pregnancies complicated by eclampsia also have higher rates of maternal morbidity such as pulmonary edema and HELLP syndrome (TABLE 1). Complications are substantially higher among women who develop antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term.1-3

TABLE 1

Maternal complications

Antepartum eclampsia, especially when it is remote from term, is much more likely to lead to complications

| COMPLICATION | RATE (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 0.5-–2 | Risk of death is higher:

|

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | <1 | Usually related to several risk factors |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 2–3 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Disseminated coagulopathy | 3–5 | Regional anesthesia is contraindicated in these patients, and there is a heightened risk of hemorrhagic shock |

| Pulmonary edema | 3–5 | Heightened risk of maternal hypoxemia and acidosis |

| Acute renal failure | 5–9 | Usually seen in association with abruptio placentae, maternal hemorrhage, and prolonged maternal hypotension |

| Abruptio placentae | 7–10 | Can occur after a convulsion; suspect it if fetal bradycardia or late decelerations persist |

| HELLP syndrome | 10–15 |

Adverse perinatal outcomes

Perinatal mortality and morbidity are high in eclampsia, with a perinatal death rate in recent series of 5.6% to 11.8%.1,7 This high rate is related to prematurity, abruptio placentae, and severe growth restriction.1

Preterm deliveries occur in approximately 50% of cases, and about 25% occur before 32 weeks’ gestation.1

Diagnosis can be tricky

When the patient has generalized edema, hypertension, proteinuria, and convulsions, diagnosis of eclampsia is straightforward. Unfortunately, women with eclampsia exhibit a broad spectrum of signs, ranging from severe hypertension, severe proteinuria, and generalized edema, to absent or minimal hypertension, nonexistent proteinuria, and no edema (TABLE 2).1

Hypertension is the hallmark of diagnosis. Hypertension is severe (at least 160 mm Hg systolic and/or at least 110 mm Hg diastolic) in 20% to 54% of cases, and it is mild (systolic pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg) in 30% to 60% of cases.2,3 In 16% of cases, there may be no hypertension at all.2

Proteinuria. Eclampsia usually is associated with proteinuria (at least 1+ on dipstick).1 However, when I studied a series of 399 women with eclampsia, I found substantial proteinuria (3+ or above on dipstick) in only 48% of cases; proteinuria was absent in 14%.2

Edema. A weight gain of more than 2 lb per week (with or without clinical edema) during the third trimester may be the first sign of eclampsia. However, in my series of 399 women, edema was absent in 26% of cases.2

TABLE 2

Signs and symptoms of eclampsia*

Hypertension and proteinuria in eclampsia may be severe, mild, or even absent

| CONDITION | FREQUENCY (%) IN WOMEN WITH ECLAMPSIA | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| SIGNS | ||

| Hypertension | 85 | Should be documented on at least 2 occasions more than 6 hours apart |

| Severe: 160/110 mm Hg or more | 20–54 | |

| Mild: 140–160/90–110 mm Hg | 30–60 | |

| No hypertension2 | 16 | |

| Proteinuria | 85 | |

| At least 1+ on dipstick2 | 48 | |

| At least 3+ on dipstick | 14 | |

| No proteinuria | 15 | |

| SYMPTOMS | ||

| At least 1 of the following: | 33–75 | Clinical symptoms may occur before or after a convulsion |

| Headache | 30–70 | Persistent, occipital, or frontal |

| Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain | 12–20 | |

| Visual changes | 19–32 | Blurred vision, photophobia |

| Altered mental changes | 4–5 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Symptoms of eclampsia

Several clinical symptoms can occur before or after a convulsion1:

- persistent occipital or frontal headaches,

- blurred vision,

- photophobia,

- epigastric and/or right upper quadrant pain, and

- altered mental status.

Usual times of onset

Eclamptic convulsions can occur during pregnancy or delivery, or after delivery ( TABLE 3).1-5

Approximately 91% of antepartum cases develop at 28 weeks or beyond. The remaining cases tend to occur between 21 and 27 weeks’ gestation (7.5%), or at or before 20 weeks (1.5%).2

When eclampsia occurs before 20 weeks, it usually involves molar or hydropic degeneration of the placenta, with or without a fetus.1 However, eclampsia can occur in the first half of pregnancy without molar degeneration of the placenta, although this is rare.1,2 These women are sometimes misdiagnosed as having hypertensive encephalopathy, seizure disorder, or thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. Thus, women who develop convulsions in association with hypertension and proteinuria in the first half of pregnancy should be assumed to have eclampsia until proven otherwise,1 and require ultrasound examination of the uterus to rule out molar pregnancy and/or hydropic or cystic degeneration of the placenta.

Postpartum cases tend to occur within the first 48 hours, although some develop beyond this limit and have been reported as late as 23 days postpartum.8

Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery.8 These women have signs and symptoms consistent with preeclampsia along with their convulsions.8,9 Thus, women who develop convulsions with hypertension and/or proteinuria, or with headaches or blurred vision, after 48 hours postpartum should be assumed to have eclampsia and treated accordingly.8,9

When eclampsia occurs especially late, perform an extensive neurologic examination to rule out other cerebral pathology.1,10

Eclampsia is atypical if convulsions occur before 20 weeks’ gestation or beyond 48 hours postpartum. It also is atypical if convulsions develop or persist despite adequate magnesium sulfate, or if the patient develops focal neurologic deficits, disorientation, blindness, or coma. In these cases, conduct a neurologic exam and cerebral imaging to exclude neurologic pathology.8-10

TABLE 3

Usual times of onset*

91% of antepartum eclampsia cases occur at 28 weeks or later, although eclamptic convulsions can occur at any time during pregnancy or delivery, or postpartum

| ONSET | FREQUENCY (%) | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Antepartum | 38–53 | Maternal and perinatal mortality, and the incidence of complications and underlying disease, are higher in antepartum eclampsia, especially in early cases |

| ≤20 weeks | 1.5 | |

| 21 to 27 weeks | 7.5 | |

| ≥28 weeks | 91 | |

| Intrapartum | 18–36 | Intrapartum eclampsia more closely resembles postpartum disease than antepartum cases |

| Postpartum | 11–44 | Late postpartum eclampsia occurs more than 48 hours but less than 4 weeks after delivery |

| ≤48 hours | 7–39 | |

| >48 hours | 5–26 | |

| * Summary of 5 series | ||

Differential diagnosis

As with other aspects of preeclampsia, the presenting symptoms, clinical findings, and many laboratory results in eclampsia overlap several other medical and surgical conditions.1,10 Of course, eclampsia is the most common cause of convulsions in a woman with hypertension and/or proteinuria during pregnancy or immediately postpartum. On rare occasions, other causes of convulsions in pregnancy or postpartum may mimic eclampsia.1 These potential diagnoses are particularly important when the woman has focal neurologic deficits, prolonged coma, or atypical eclampsia.

The differential diagnosis encompasses a variety of cerebrovascular and metabolic disorders:

- hemorrhage,

- ruptured aneurysm or malformation,

- arterial embolism, thrombosis,

- venous thrombosis,

- hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy,

- angiomas,

- hypertensive encephalopathy,

- seizure disorder,

- hypoglycemia, hyponatremia,

- posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome,

- thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura,

- postdural puncture syndrome, and

- cerebral vasculitis/angiopathy.

Other diseases may factor in

Some women develop gestational hypertension or preeclampsia in association with connective tissue disease, thrombophilias, seizure disorder, or hypertensive encephalopathy, further confounding the diagnosis.

Thus, make every effort to ensure a correct diagnosis, since management may differ among these conditions.

Managing convulsions

Do not try to stop the first convulsion

The natural tendency is to try and interrupt the convulsion, but this is not recommended. Nor should you give a drug such as diazepam to shorten or stop the convulsion, especially if the patient lacks an intravenous line and no one skilled in intubation is immediately available. If diazepam is given, do not exceed 5 mg over 60 seconds. Rapid administration of this drug may lead to apnea or cardiac arrest, or both.

Steps to prevent maternal injury

During or immediately after the acute convulsive episode, take steps to prevent serious maternal injury and aspiration, assess and establish airway patency, and ensure maternal oxygenation (TABLE 4).

Elevate and pad the bed’s side rails and insert a padded tongue blade between the patient’s teeth, taking care not to trigger the gag reflex.

Physical restraints also may be needed.

Prevent aspiration. To minimize the risk of aspiration, place the patient in the lateral decubitus position, and suction vomitus and oral secretions as needed. Be aware that aspiration can occur when the padded tongue blade is forced to the back of the throat, stimulating the gag reflex and resultant vomiting.

TABLE 4

During a convulsion, 3 spheres of concern

| AVOID MATERNAL INJURY |

| Insert padded tongue blade |

| Avoid inducing gag reflex |

| Elevate padded bedside rails |

| Use physical restraints as needed |

| MAINTAIN OXYGENATION TO MOTHER AND FETUS |

| Apply face mask with or without oxygen reservoir at 8–10 L/minute |

| Monitor oxygenation and metabolic status via |

| Transcutaneous pulse oximetry |

| Arterial blood gases (sodium bicarbonate administered accordingly) |

| Correct oxygenation and metabolic status before administering anesthetics that may depress myocardial function |

| MINIMIZE ASPIRATION |

| Place patient in lateral decubitus position (which also maximizes uterine blood flow and venous return) |

| Suction vomitus and oral secretions |

| Obtain chest x-ray after the convulsion is controlled to rule out aspiration |

Tips on supplemental oxygenation

Although the initial seizure lasts only a minute or 2, it is important to maintain oxygenation by giving supplemental oxygen via a face mask, with or without an oxygen reservoir, at 8 to 10 L per minute. This is important because hypoventilation and respiratory acidosis often occur.

Once the convulsion ends and the patient resumes breathing, oxygenation is rarely a problem. However, maternal hypoxemia and acidosis can develop in women with repetitive convulsions, aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or a combination of these factors. Thus, transcutaneous pulse oximetry is advisable to monitor oxygenation in eclamptic patients.

Arterial blood gas analysis is necessary if pulse oximetry shows abnormal oxygen saturation (ie, at or below 92%).

Strategy to prevent recurrence

Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice to treat and prevent subsequent convulsions in women with eclampsia.1,2

Dosage. I give a loading dose of 6 g over 15 to 20 minutes, followed by a maintenance dose of 2 g per hour as a continuous intravenous solution.

Approximately 10% of eclamptic women have a second convulsion after receiving magnesium sulfate.1,2 When this occurs, I give another 2-g bolus intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

More rarely, a woman will continue to have convulsions while receiving adequate and therapeutic doses of magnesium sulfate.

I treat such patients with sodium amobarbital, 250 mg, intravenously over 3 to 5 minutes.

Monitor maternal magnesium levels

Plasma levels should be in the range of 4 to 8 mg/dL during treatment for eclampsia, and are determined by the volume of distribution and by renal excretion. Thus, it is important to monitor the patient for magnesium toxicity, particularly if she has renal dysfunction (serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or above) or urine output below 100 mL in 4 hours. In these women, adjust the maintenance dose according to plasma levels.

Side effects of magnesium including flushing, a feeling of warmth, nausea and vomiting, double vision, and slurred speech (TABLE 5).

If magnesium toxicity is suspected, immediately discontinue the infusion and administer supplemental oxygen along with 10 mL of 10% calcium gluconate (1 g total) as an intravenous push slowly over 5 minutes.

If respiratory arrest occurs, prompt resuscitation—including intubation and assisted ventilation—is vital.

TABLE 5

Clinical manifestations of magnesium toxicity

Maternal plasma levels of 4 to 8 mg/dL are appropriate during treatment for eclampsia; higher levels signal toxicity

| IF THE MAGNESIUM LEVEL IS… | THE CLINICAL MANIFESTATION IS… |

|---|---|

| 8–12 mg/dL | Loss of patellar reflex |

| Double or blurred vision | |

| Headache and nausea | |

| 9–12 mg/dL | Feeling of warmth, flushing |

| 10–12 mg/dL | Somnolence |

| Slurred speech | |

| 15–17 mg/dL | Muscular paralysis |

| Respiratory arrest | |

| 30–35 mg/dL | Cardiac arrest |

Controlling severe hypertension

The next step is to reduce blood pressure to a safe range. The objective: to preserve cerebral autoregulation and prevent congestive heart failure without compromising cerebral perfusion or jeopardizing uteroplacental blood flow, which is already reduced in many women with eclampsia.1

To these ends, try to keep systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mm Hg and diastolic pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg. This can be achieved with:

- bolus 5- to 10-mg doses of hydralazine,

- 20 to 40 mg labetalol intravenously every 15 minutes, as needed, or

- 10 to 20 mg oral nifedipine every 30 minutes.

Other potent antihypertensive drugs such as sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerine are rarely needed in eclampsia, and diuretics are indicated only in the presence of pulmonary edema.

Intrapartum management

Maternal hypoxemia and hypercarbia cause fetal heart rate and uterine activity changes during and immediately following a convulsion.

Fetal heart rate changes

These can include bradycardia, transient late decelerations, decreased beat-to-beat variability, and compensatory tachycardia.

The interval from onset of the seizure to the fall in fetal heart rate is approximately 5 minutes (FIGURE 1). Transitory fetal tachycardia frequently occurs after the prolonged bradycardia. The loss of beat-to-beat variability, with transitory late decelerations, occurs during the recovery phase.

The mechanism for the transient fetal bradycardia may be intense vasospasm and uterine hyperactivity, which may decrease uterine blood flow. The absence of maternal respiration during the convulsion may also contribute to fetal heart rate changes.

Since the fetal heart rate usually returns to normal after a convulsion, other conditions should be considered if an abnormal pattern persists.

In some cases, it may take longer for the heart rate pattern to return to baseline if the fetus is preterm with growth restriction.

Placental abruption may occur after the convulsion and should be suspected if fetal bradycardia or repetitive late decelerations persist (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1 Fetal response to a convulsion The top 2 tracings show fetal bradycardia during an eclamptic convulsion

FIGURE 2 Abruptio placentae Repetitive late decelerations secondary to abruptio placentae, necessitating cesarean section

Uterine activity

During a convulsion, contractions can increase in frequency and tone. The duration of increased uterine activity varies from 2 to 14 minutes.

These changes usually resolve spontaneously within 3 to 10 minutes following the termination of convulsions and correction of maternal hypoxemia (FIGURE 1).

If uterine hyperactivity persists, suspect placental abruption (FIGURE 2).

Do not rush to cesarean

It benefits the fetus to allow in utero recovery from the maternal convulsion, hypoxia, and hypercarbia before delivery. However, if the bradycardia and/or recurrent late decelerations persist beyond 10 to 15 minutes despite all efforts, suspect abruptio placentae or nonreassuring fetal status.

Once the patient regains consciousness and is oriented to name, place, and time, and her convulsions are controlled and condition stabilized, proceed with delivery.

Choosing a delivery route

Eclampsia is not an indication for cesarean. The decision to perform a cesarean should be based on fetal gestational age, fetal condition, presence of labor, and cervical Bishop score. I recommend:

- Cesarean section for women with eclampsia before 30 weeks’ gestation who are not in labor and whose Bishop score is below 5.

- Vaginal delivery for women in labor or with rupture of membranes, provided there are no obstetric complications.

- Labor induction with oxytocin infusion or prostaglandins in all women at or after 30 weeks, regardless of the Bishop score, and in women before 30 weeks when the Bishop score is 5 or above.

Maternal pain relief

During labor and delivery, systemic opioids or epidural anesthesia can provide pain relief—the same recommendations as for women with severe preeclampsia.

For cesarean delivery, an epidural, spinal, or combined techniques of regional anesthesia are suitable.

Do not use regional anesthesia if there is coagulopathy or severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 50,000/mm3). In women with eclampsia, general anesthesia increases the risk of aspiration and failed intubation due to airway edema, and is associated with marked increases in systemic and cerebral pressures during intubation and extubation.

Women with airway or laryngeal edema may require awake intubation under fiber optic observation, with tracheostomy immediately available.

Changes in systemic or cerebral pressures may be attenuated by pretreatment with labetalol or nitroglycerine injections.

Postpartum management

After delivery, women with eclampsia require close monitoring of vital signs, fluid intake and output, and symptoms for at least 48 hours.

Risk of pulmonary edema

These women usually receive large amounts of intravenous fluids during labor, delivery, and postpartum. In addition, during the postpartum period, extracellular fluid mobilizes, leading to increased intravascular volume.

As a result, women who develop eclampsia—particularly those with abnormal renal function, abruptio placentae, and/or preexisting chronic hypertension— face an increased risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension.2

Frequent evaluation of the amount of intravenous fluids is necessary, as well as oral intake, blood products, and urine output. They also need pulse oximetry and pulmonary auscultation.

Continue magnesium sulfate

Parenteral magnesium sulfate should be given for at least 24 hours after delivery and/or for at least 24 hours after the last convulsion.

If the patient has oliguria (less than 100 mL over 4 hours), both fluid administration and the dose of magnesium sulfate should be reduced.

Oral antihypertensives

Other oral antihypertensive agents such as labetalol or nifedipine can be given to keep systolic blood pressure below 155 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. Nifedipine offers the benefit of improved diuresis in the postpartum period.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Sibai BM. Diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:402-410.

2. Mattar F, Sibai BM. Eclampsia VIII. Risk factors for maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:307-312.

3. Douglas KA, Redman CW. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1994;309:1395-1400.

4. Rugard O, Carling MS, Berg G. Eclampsia at a tertiary hospital, 1973–99. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:240-245.

5. Katz VL, Farmer R, Kuller J. Preeclampsia into eclampsia: toward a new paradigm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1389-1396.

6. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:533-538.

7. Leitch CR, Cameron AD, Walker JJ. The changing pattern of eclampsia over a 60-year period. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:917-922.

8. Lubarsky SL, Barton JR, Friedman SA, Nasreddine S, Ramaddan MK, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia revisited. Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;83:502-505.

9. Chames MC, Livingston JC, Ivester TS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia: a preventable disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1174-1177.

10. Witlin AG, Friedman SA, Egerman RS, Frangieh AY, Sibai BM. Cerebrovascular disorders complicating pregnancy. Beyond eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:139-148.

1. Sibai BM. Diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:402-410.

2. Mattar F, Sibai BM. Eclampsia VIII. Risk factors for maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:307-312.

3. Douglas KA, Redman CW. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1994;309:1395-1400.

4. Rugard O, Carling MS, Berg G. Eclampsia at a tertiary hospital, 1973–99. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:240-245.

5. Katz VL, Farmer R, Kuller J. Preeclampsia into eclampsia: toward a new paradigm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1389-1396.

6. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:533-538.

7. Leitch CR, Cameron AD, Walker JJ. The changing pattern of eclampsia over a 60-year period. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:917-922.

8. Lubarsky SL, Barton JR, Friedman SA, Nasreddine S, Ramaddan MK, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia revisited. Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;83:502-505.

9. Chames MC, Livingston JC, Ivester TS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia: a preventable disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1174-1177.

10. Witlin AG, Friedman SA, Egerman RS, Frangieh AY, Sibai BM. Cerebrovascular disorders complicating pregnancy. Beyond eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:139-148.