User login

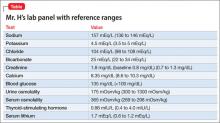

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

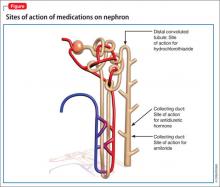

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.