User login

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

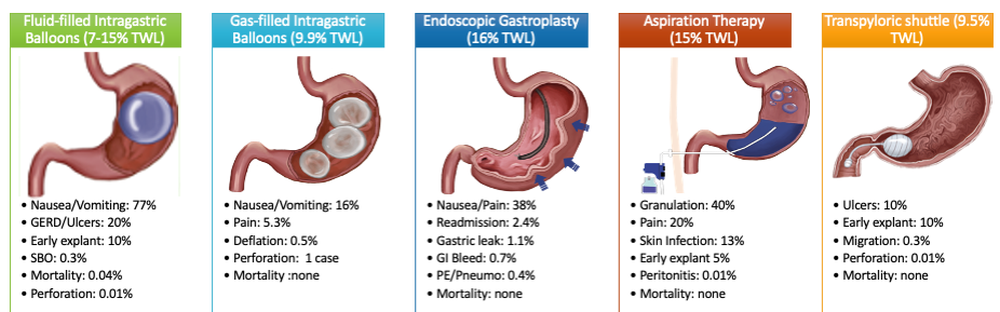

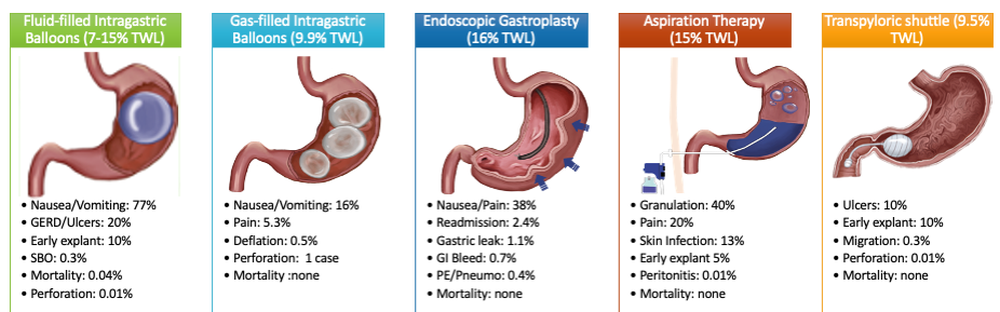

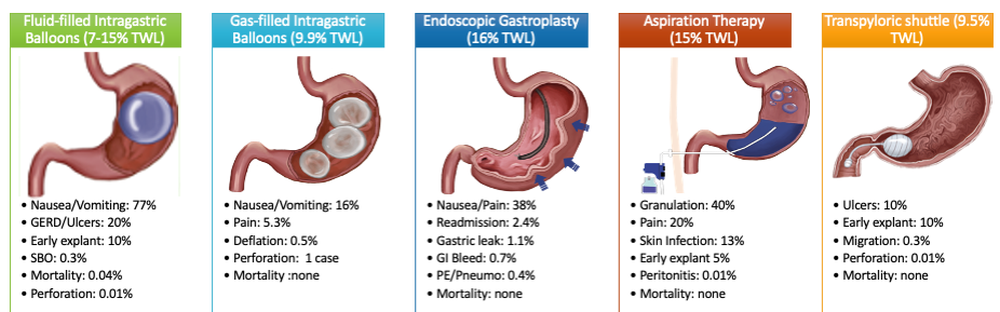

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

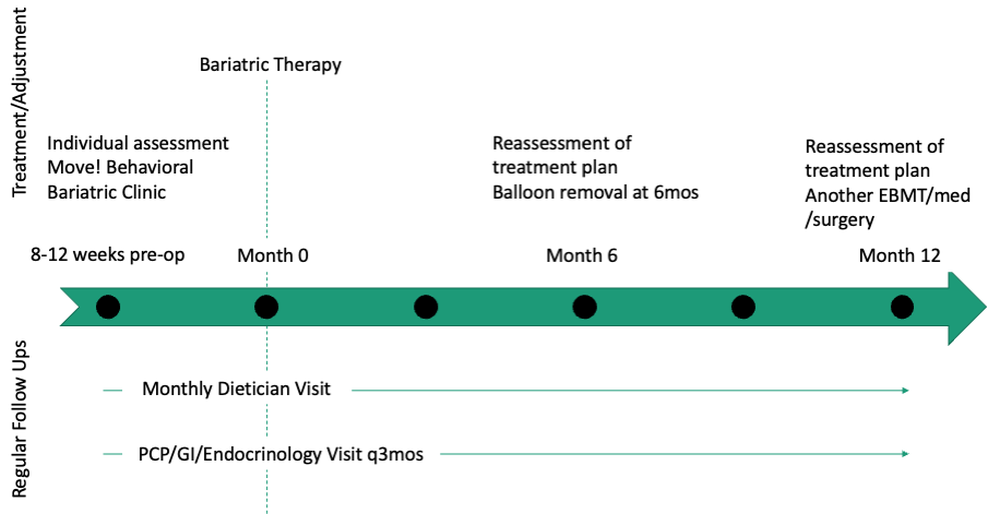

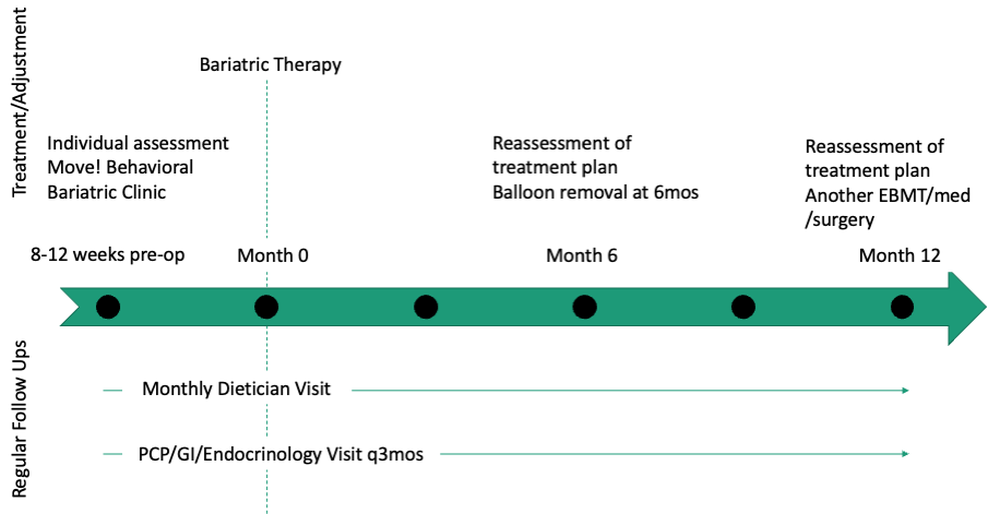

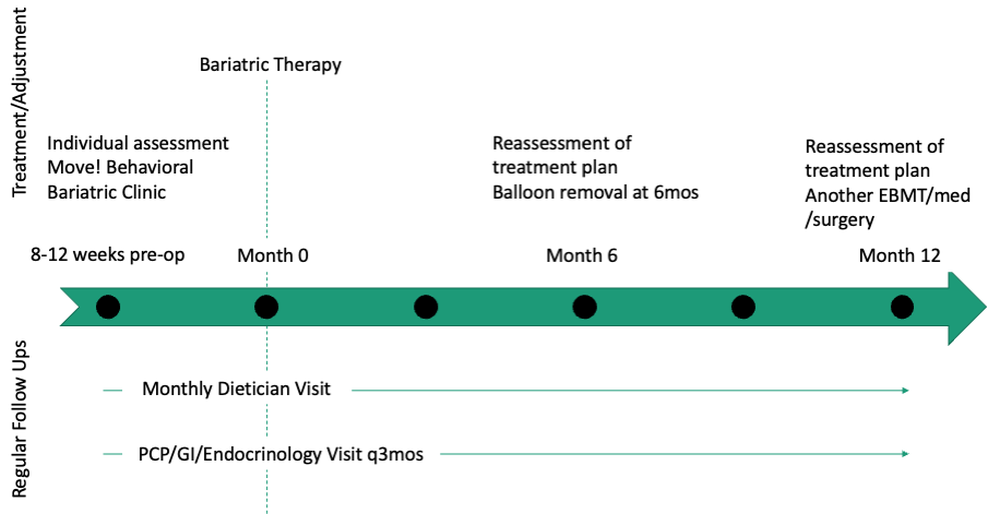

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

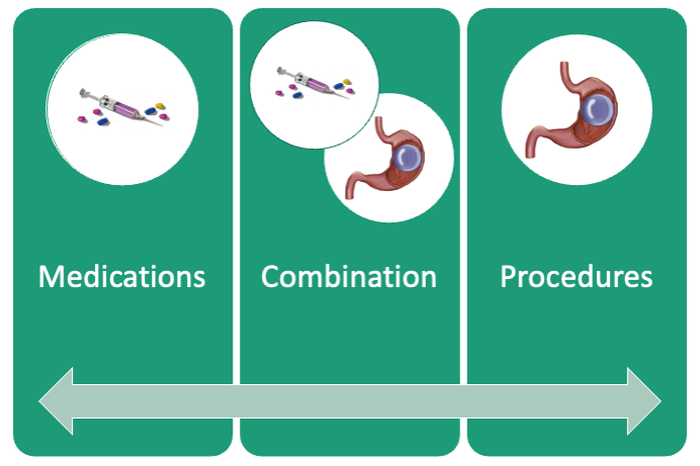

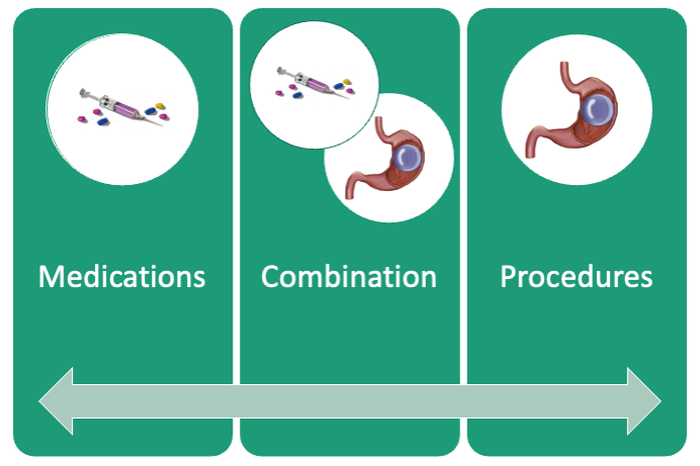

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.