User login

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

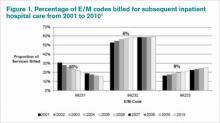

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Reference

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.

To address tricky issues that come up only occasionally, several in our practice have compiled a “coding manual” by distilling guidance from our certified coders and compliance people on issues as they came up. Some issues would stump all of us, and we’d have to go to the Internet for help. All hospitalists are provided with a copy of the manual during orientation, and an electronic copy is available on the hospital’s Intranet. Topics addressed in the manual include things like how to bill the first inpatient day when a patient has changed from observation status, how to bill initial consult visits for various payors (an issue since Medicare eliminated consult codes a few years ago), how to bill when a patient is seen and discharged from the ED, etc.

Lastly, I suggest someone in your group talk with your hospital’s compliance department about its own coding and billing compliance plan. This could lead to ideas or help develop a compliance plan for your group.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.