User login

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health problem with considerable harmful health consequences. Decades of research have been dedicated to improving the identification of women in abusive heterosexual relationships and interventions that support healthier outcomes. A result of this work has been the recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV and provided with intervention or referral.1

The problem extends further, however: Epidemiologic studies and comprehensive reviews show: 1) a high rate of IPV victimization among heterosexual men and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual (LGBT) men and women2,3; 2) significant harmful effects on health and greater expectations of prejudice and discrimination among these populations4-6; and 3) evidence that screening and referral for IPV are likely to confer similar benefits for these populations.7 We argue that it is reasonable to ask all patients about abuse in their relationships while the research literature progresses.

We intend this article to serve a number of purposes:

- support national standards for IPV screening of female patients

- highlight the need for piloting universal IPV screening for all patients (ie, male and female, across the lifespan)

- offer recommendations for navigating the process from IPV screening to referral, using insights gained from the substance abuse literature.

We also provide supplemental materials that facilitate establishment of screening and referral protocols for physicians across practice settings.

What is intimate partner violence? How can you identify it?

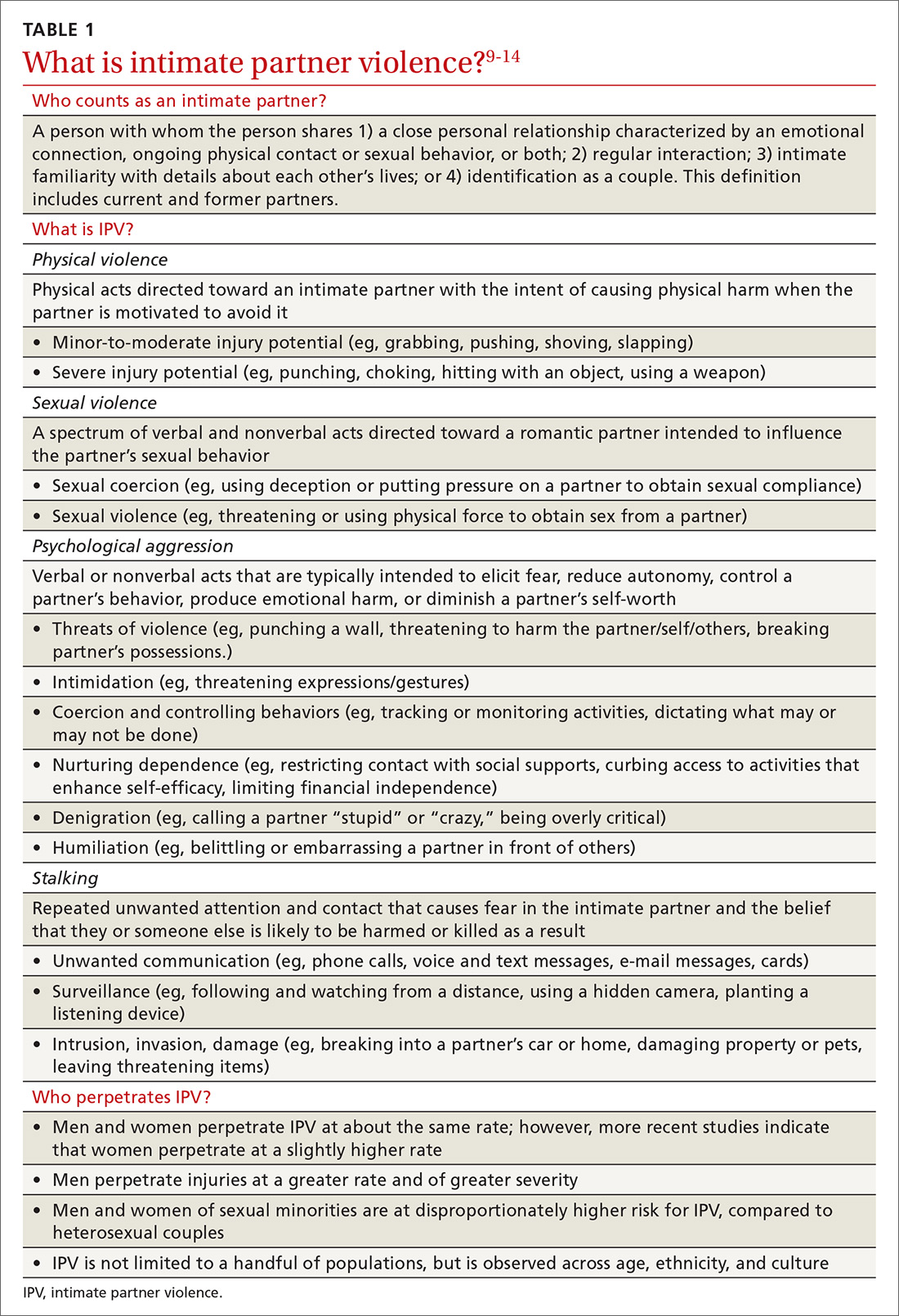

Intimate partner violence includes physical and sexual violence and nonphysical forms of abuse, such as psychological aggression and emotional abuse, perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner.8 TABLE 19-14 provides definitions for each of these behavior categories and example behaviors. Nearly 25% of women and 20% of men report having experienced physical violence from a romantic partner and even higher rates of nonphysical IPV.15 Consequences of IPV victimization include acute and chronic medical illness, injury, and psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and poor self-esteem.16

Intimate partner violence is heterogeneous, with differences in severity (eg, frequency and intensity of violence) and laterality (ie, is one partner violent? are both partners violent?). A recent comprehensive review of the literature revealed that, for 49.2%-69.7% of partner-violent couples across diverse samples, IPV is perpetrated by both partners.17 Furthermore, this bidirectionality is not due entirely to aggression perpetrated in self-defense; rather, across diverse patient samples, that is the case for fewer than one-quarter of males and no more than approximately one-third of females.18 In the remaining cases, bidirectionality may be attributed to other motivations, such as a maladaptive emotional expression or a means by which to get a partner’s attention.18

Women are disproportionately susceptible to harmful outcomes as a result of severe violence, including physical injury, psychological distress (eg, depression and anxiety), and substance abuse.16,19 Some patients in unidirectionally violent relationships experience severe physical violence that may be, or become, life-threatening (0.4%-2.4% of couples in community samples)20—victimization that is traditionally known as “battering.”21

Continue to: These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

Physicians might have reservations asking about IPV because of 1) concern whether there is sufficient time during an office visit to interview, screen, and refer, 2) feelings of powerlessness to stop violence by or toward a patient, and 3) general discomfort with the topic.22 Additionally, mandated reporting laws regarding IPV vary by state, making it crucial to know one’s own state laws on this issue to protect the safety of the patient and those around them.

Research has shown that some patients prefer that their health care providers ask about relationship violence directly23; others are more willing to acknowledge IPV if asked using a paper-and-pencil measure, rather than face-to-face questions.24 Either way, screening increases the likelihood of engaging the patient in supportive services, thus decreasing the isolation that is typical of abuse.25 Based on this research, screening that utilizes face-valid items embedded within paperwork completed in the waiting room is recommended as an important first step toward identifying and helping patients who are experiencing IPV. Even under these conditions, however, heterosexual men and sexual minorities might be less willing than heterosexual women to admit experiencing IPV.26,27

A brief vignette that depicts how quickly the screening and referral process can be applied is presented in “IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette." The vignette is a de-identified composite of heterosexual men experiencing IPV whom we have counseled.

SIDEBAR

IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette

Physician: Before we wrap up: I noticed on your screening that you have been hurt and threatened a fair amount in the past year. Would it be OK if we spoke about that more?

Patient: My wife is emotional. Sometimes she gets really stressed out and just starts screaming and punching me. That’s just how she is.

Physician: Do you ever feel concerned for your safety?

Patient: Not really. She’s smaller than me and I can generally calm her down. I keep the guns locked up, so she can’t grab those any more. Mostly she just screams at me.

Physician: This may or may not fit with your perception but, based on what you are reporting, your relationship is what is called “at risk”—meaning you are at risk for having your physical or mental health negatively impacted. This actually happens to a lot of men, and there’s a brochure I can give you that has a lot more information about the risks and consequences of being hurt or threatened by a partner. Would you be willing to take a look at it?

Patient: I guess so.

Physician: OK. I’ll have the nurse bring you that brochure, and we can talk more about it next time you come in for an appointment. Would it be OK if we get you back in here 6 months from now?

Patient: Yeah, that could work.

Physician: Great. Let’s do that. Don’t hesitate to give me a call if your situation changes in any way in the meantime.

One model that provides a useful framework for IPV assessment is the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model, which was developed to facilitate assessment of, and referral for, substance abuse—another heavily stigmatized health care problem. The SBIRT approach for substance abuse screening is associated with significant reduction in alcohol and drug abuse 6 months postintervention, as well as improvements in well-being, mental health, and functioning across gender, race and ethnicity, and age.28

IPASSPRT. Inspired by the SBIRT model for substance abuse, we created the Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment, or IPASSPRT (spoken as “i-passport”) project to provide tools that make IPV screening and referral accessible to a range of health care providers. These tools include a script and safety plan that guide providers through screening, safety planning, and referral in a manner that is collaborative and grounded in the spirit of motivational interviewing. We have made these tools available on the Web for ease of distribution (http://bit.ly/ipassprt; open by linking through “IPASSPRT-Script”).

Continue to: The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy...

The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy, but progress through its sections is directed by patient need; most patients will not require that all parts be completed. For example, a patient whose screen for IPV is negative and who feels safe in their relationship does not need assessment beyond page 2; on the other hand, the physician might need more information from a patient who is at greater risk for IPV. This response-based progression through the script makes the screening process dynamic, data-driven, and tailored to the patient’s needs—an approach that aids rapport and optimizes the physician’s limited time during the appointment.

In the sections that follow, we describe key components of this script.

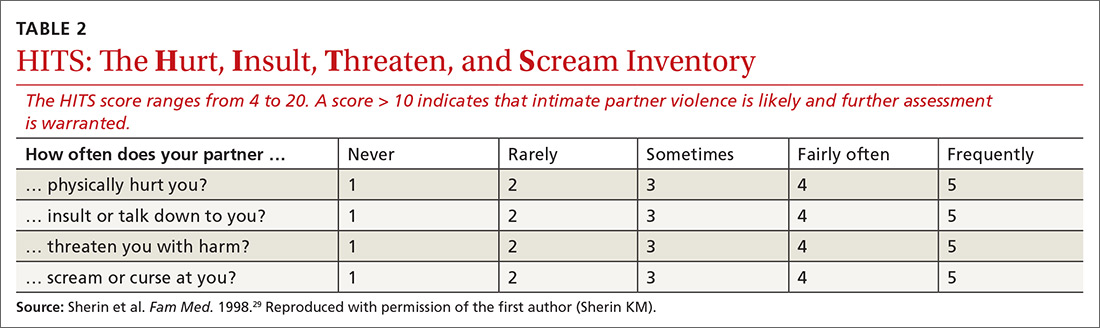

What aggression, if any, is present? From whom? The Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream inventory (HITS) (TABLE 2)29 is a widely used screen for IPV that has been validated for use in family medicine. A 4-item scale asks patients to report how often their partner physically hurts, insults, threatens, and screams at them using a 5-point scale (1 point, “never,” to 5 points, “frequently”). Although a score > 10 is indicative of IPV, item-level analysis is encouraged. Attending to which items the patient acknowledges and how often these behaviors occur yields a richer assessment than a summary score. In regard to simply asking a patient, “Do you feel safe at home?” (sensitivity of this question, 8.8%; specificity, 91.2%), the HITS better detects IPV with male and female patient populations in family practice and emergency care settings (sensitivity, 30%-100%; specificity, 86%-99%).27,30

What contextual factors and related concerns are present? It is important to understand proximal factors that might influence IPV risk to determine what kind of referral or treatment is appropriate—particularly for patients experiencing or engaging in infrequent, noninjurious, and bidirectional forms of IPV. Environmental and contextual stressors, such as financial hardship, unemployment, pregnancy, and discussion of divorce, can increase the risk for IPV.31,32 Situational influences, such as alcohol and drug intoxication, can also increase the risk for IPV. Victims of partner violence are at greater risk for mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, and substance use disorders. Risk goes both ways, however: Mental illness predicts subsequent IPV perpetration or victimization, and vice versa.31

Does the patient feel safe? Assessing the situation. Patient perception of safety in the relationship provides important information about the necessity of referral. Asking a patient if they feel unsafe because of the behavior of a current or former partner sheds light on the need for further safety assessment and immediate connection with appropriate resources.

Continue to: The Danger Assessment-5...

The Danger Assessment-5 (DA-5) (TABLE 333) is a useful 5-item tool for quickly assessing the risk for severe IPV.33 Patients respond to whether:

- the frequency or severity of violence has increased in the past year

- the partner has ever used, or threatened to use, a weapon

- the patient believes the partner is capable of killing her (him)

- the partner has ever tried to choke or strangle her (him)

- the partner is violently and constantly jealous.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses with a high-risk female sample suggested that 3 affirmative responses indicate a high risk for severe IPV and a need for adequate safety planning.

Brief motivational enhancement intervention. There are 3 components to this intervention.

- Assess interest in making changes or seeking help. IPV is paradoxical: Many factors complicate the decision to leave or stay, and patients across the spectrum of victimization might have some motivation to stay with their partner. It is important to assess the patient’s motivation to make changes in their relationship.4,34

- Provide feedback on screening. Sharing the results of screening with patients makes the assessment and referral process collaborative and transparent; collaborative engagement helps patients feel in control and invested in the follow-through.35 In the spirit of this endeavor, physicians are encouraged to refrain from providing raw or total scores from the measures; instead, share the interpretation of those scores, based on the participant’s responses to the screening items, in a matter-of-fact manner. At this point, elicit the patient’s response to this information, listen empathically, and answer questions before proceeding.

Consistent with screening for other serious health problems, we recommend that all patients be provided with information about abuse in romantic relationships. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention has published a useful, easy-to-understand fact sheet (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf) that provides an overview of IPV-related behavior, how it influences health outcomes, who is at risk for IPV, and sources for support.

Continue to: Our IPASSPRT interview script...

Our IPASSPRT interview script (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) outlines how this information can be presented to patients as a typical part of the screening process. Providers are encouraged to share and review the information from the fact sheet with all patients and present it as part of the normal screening process to mitigate the potential for defensiveness on the part of the patient. For patients who screen positive for IPV, it might be important to brainstorm ideas for a safe, secure place to store this fact sheet and other resources from the brief intervention and referral process below (eg, a safety plan and specific referral information) so that the patient can access them quickly and easily, if needed.

For patients who screen negative for IPV, their screen and interview conclude at this point.

- Provide recommendations based on the screen. Evidence suggests that collaborating with the patient on safety planning and referral can increase the likelihood of their engagement.7 Furthermore, failure to tailor the referral to the needs of the patient can be detrimental36—ie, overshooting the level of intervention might decrease the patient’s future treatment-seeking behavior and undermine their internal coping strategies, increasing the likelihood of future victimization. For that reason, we provide the following guidance on navigating the referral process for patients who screen positive for IPV.

Screening-based referral: A delicate and collaborative process

Referral for IPV victimization. Individual counseling, with or without an IPV focus, might be appropriate for patients at lower levels of risk; immediate connection with local IPV resources is strongly encouraged for patients at higher risk. This is a delicate, collaborative process, in which the physician offers recommendations for referral commensurate to the patient’s risk but must, ultimately, respect the patient’s autonomy by identifying referrals that fit the patient’s goals. We encourage providers to provide risk-informed recommendations and to elicit the patient’s thoughts about that information.

Several online resources are available to help physicians locate and connect with IPV-related resources in their community, including the National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence (http://ipvhealth.org/), which provides a step-by-step guide to making such connections. We encourage physicians to develop these collaborative partnerships early to facilitate warm handoffs and increase the likelihood that a patient will follow through with the referral after screening.37

Referral for related concerns. As we’ve noted, IPV has numerous physical and mental health consequences, including depression, low self-esteem, trauma- and non-trauma-related anxiety, and substance abuse. In general, cognitive behavioral therapies appear most efficacious for treating these IPV-related consequences, but evidence is limited that such interventions diminish the likelihood of re-victimization.38 Intervention programs that foster problem-solving, solution-seeking, and cognitive restructuring for self-critical thoughts and misconceptions seem to produce the best physical and mental health outcomes.39 For patients who have a substance use disorder, treatment programs that target substance use have demonstrated a reduction in the rate of IPV recidivism.40 These findings indicate that establishing multiple treatment targets might reduce the risk for future aggression in relationships.

Continue to: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration...

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides a useful online tool (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/) for locating local referrals that address behavioral health and substance-related concerns. The agency also provides a hotline (1-800-662-HELP [4357]) as an alternative resource for information and treatment referrals.

Safety planning can improve outcomes

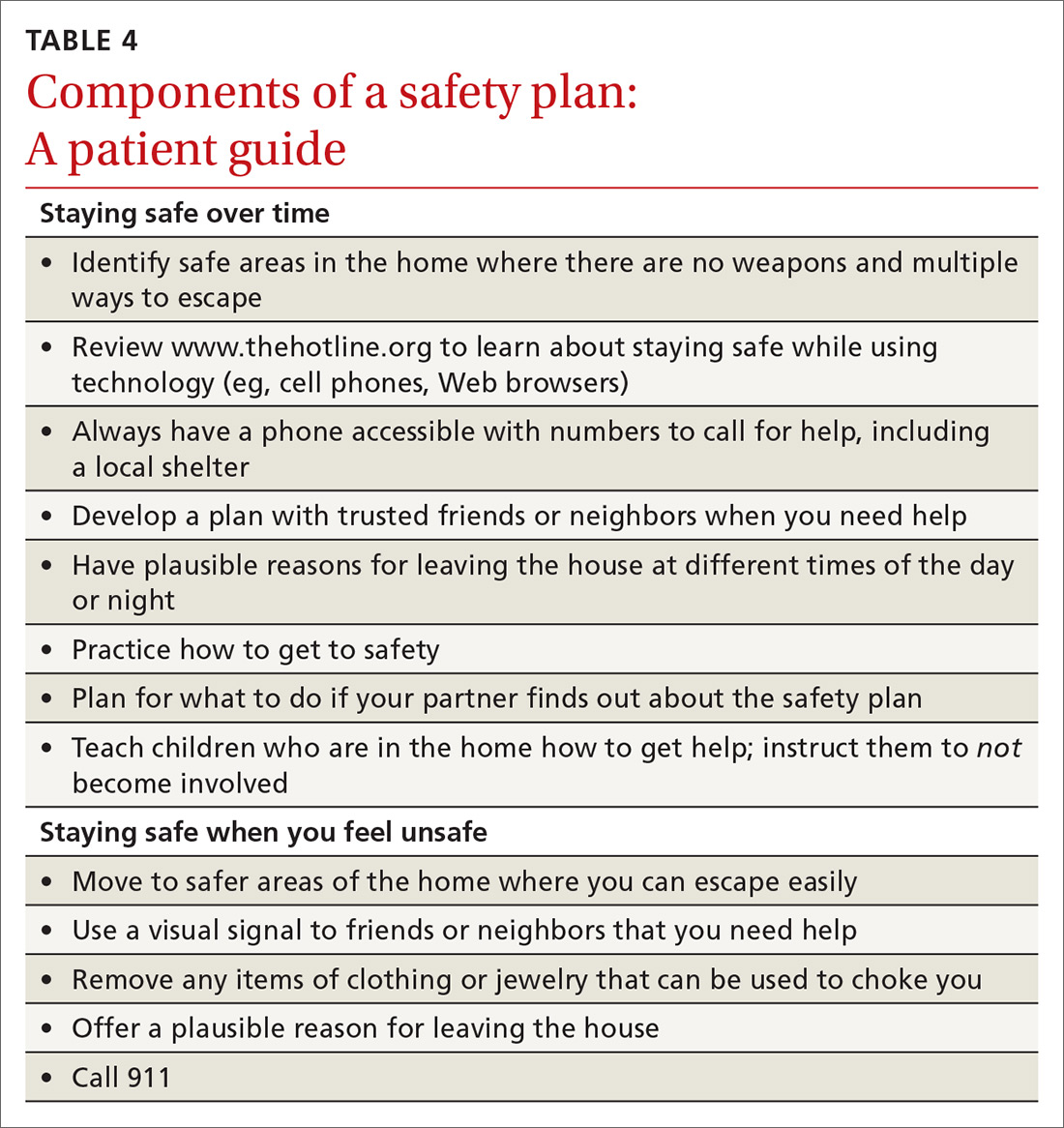

For a patient who screens above low risk, safety planning with the patient is an important part of improving outcomes and can take several forms. Online resources, such as the Path to Safety interactive Web page (www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/) maintained by The National Domestic Violence Hotline ([800]799-SAFE [7233]), provide information regarding important considerations for safety planning when:

- living with an abusive partner

- children are in the home

- the patient is pregnant

- pets are involved.

The Web site also provides information regarding legal options and resources related to IPV (eg, an order of protection) and steps for improving safety when leaving an abusive relationship. Patients at risk for IPV can explore the online tool and call the hotline.

For physicians who want to engage in provider-assisted safety planning, we’ve provided further guidance in the IPASSPRT screening script and safety plan (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) (TABLE 4).

Goal: Affirm patients’ strengths and reinforce hope

Psychological aggression is the most common form of relationship aggression; repeated denigration might leave a person with little confidence in their ability to change their relationship or seek out identified resources. That’s why it’s useful to inquire—with genuine curiosity—about a time in the past when the patient accomplished something challenging. The physician’s enthusiastic reflection on this achievement can be a means of highlighting the patient’s ability to accomplish a meaningful goal; of reinforcing their hope; and of eliciting important resources within and around the patient that can facilitate action on their safety plan. (See “IPV-related resources for physicians and patients.”)

SIDEBAR

IPV-related resources for physicians and patients

Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment (IPASSPRT) Project

› http://bit.ly/ipassprt

Online resource with tools designed by the authors, including an SBIRT-inspired script and safety plan template for IPV screening, safety planning, and referral

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention

› www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf

Overview of IPV-related behavior, influence on health outcomes, people at risk of IPV, and sources of support, all in a format easily understood by patients

National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence

› http://ipvhealth.org/

Includes guidance on connecting with IPV-related community resources; establishing such connections can facilitate warm handoffs and improve the likelihood that patients will follow through

Path to Safety, a service of The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/

Extensive primer on safety plans for patients intending to stay in (or leave) an abusive relationship; includes important considerations for children, pets, and pregnancy, as well as emotional safety and legal options

The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› (800) 799-SAFE (7233)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

› www.samhsa.gov/sbirt

Learning resources for the SBIRT protocol for substance abuse

› https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/

Search engine and resources for locating local referrals

› (800) 662-HELP (4357)

Hotline for information and assistance with locating local treatment referral

IPV, intimate partner violence; SBIRT, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment.

Continue to: Closing the screen and making a referral

Closing the screen and making a referral

The end of the interview should consist of a summary of topics discussed, including:

- changes that the patient wants to make (if any)

- their stated reasons for making those changes

- the patient’s plan for accomplishing changes.

Physicians should also include their own role in next steps—whether providing a warm handoff to a local IPV referral, agreeing to a follow-up schedule with the patient, or making a call as a mandated reporter. To close out the interview, it is important to affirm respect for the patient’s autonomy in executing the plan.

It’s important to screen all patients—here’s why

A major impetus for this article has been to raise awareness about the need for expanded IPV screening across primary care settings. As mentioned, much of the literature on IPV victimization has focused on women; however, the few epidemiological investigations of victimization rates among men and members of LGBT couples show a high rate of victimization and considerable harmful health outcomes. Driven by stigma surrounding IPV, sex, and sexual minority status, patients might have expectations that they will be judged by a provider or “outed.”

Such barriers can lead many to suffer in silence until the problem can no longer be hidden or the danger becomes more emergent. Compassionate, nonjudgmental screening and collaborative safety planning—such as the approach we describe in this article—help ease the concerns of LGBT victims of IPV and improve the likelihood that conversations you have with them will occur earlier, rather than later, in care.*

Underassessment of IPV (ie, underreporting as well as under-inquiry) because of stigma, misconception, and other factors obscures an accurate estimate of the rate of partner violence and its consequences for all couples. As a consequence, we know little about the dynamics of IPV, best practices for screening, and appropriate referral for couples from these populations. Furthermore, few resources are available to these understudied and underserved groups (eg, shelters for men and for transgender people).

Continue to: Although our immediate approach to IPV screening...

Although our immediate approach to IPV screening, safety planning, and referral with understudied patient populations might be informed by what we have learned from the experiences of heterosexual women in abusive relationships, such a practice is unsustainable. Unless we expand our scope of screening to all patients, it is unlikely that we will develop the evidence base necessary to 1) warrant stronger IPV screening recommendations for patient groups apart from women of childbearing age, let alone 2) demonstrate the need for additional community resources, and 3) provide comprehensive care in family practice of comparable quality.

The benefits of screening go beyond the individual patient

Screening for violence in the relationship does not take long; the value of asking about its presence in a relationship might offer benefits beyond the individual patient by raising awareness and providing the field of study with more data to increase attention and resources for under-researched and underserved populations. Screening might also combat the stigma that perpetuates the silence of many who deserve access to care.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel G. Sprunger, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 260 Stetson St, Suite 3200, Cincinnati OH 45219; joel.sprunger@UC.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jeffrey M. Girard, PhD, and Daniel C. Williams, PhD, for their input on the design and content, respectively, of the IPASSPRT screening materials; the authors of the DA-5 and the HITS screening tools, particularly Jacquelyn Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN, and Kevin Sherin, MD, MPH, MBA, respectively, for permission to include these measures in this article and for their support of its goals; and The Journal of Family Practice’s peer reviewers for their thoughtful feedback throughout the prepublication process.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF: What’s recommended, what’s not. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:265-269.

2. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011:113. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2019.

3. West CM. Partner abuse in ethnic minority and gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:336-357.

4. Hines DA, Malley-Morrison K. Psychological effects of partner abuse against men: a neglected research area. Psychology of Men & Masculinities. 2001;2:75-85.

5. Houston E, McKirnan DJ. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: risk correlates and health outcomes. J Urban Health. 2007;84:681-690.

6. Carvalho AF, Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, et al. Internalized sexual minority stressors and same-sex intimate partner violence. J Fam Violence. 2011;26:501-509.

7. Nicholls TL, Pritchard MM, Reeves KA, et al. Risk assessment in intimate partner violence: a systematic review of contemporary approaches. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:76-168.

8. Intimate partner violence: definitions. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 22, 2017. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html. Accessed February 20, 2019.

9. Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:651-680.

10. Baron RA, Richardson DR. Human Aggression. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2004.

11. Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, et al. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015.

12. Murphy CM, Eckhardt CI. Treating the Abusive Partner: An Individualized Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005.

13. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:283-316.

14. West CM. Partner abuse in ethnic minority and gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:336-357.

15. Desmarais SL, Reeves KA, Nicholls TL, et al. Prevalence of physical violence in intimate relationships. Part 1: rates of male and female victimization. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:140-169.

16. Lawrence E, Orengo-Aguayo R, Langer A, et al. The impact and consequences of partner abuse on partners. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:406-428.

17. Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: a comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199-230.

18. Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, McCullars A, Misra TA. Motivations for men and women’s intimate partner violence perpetration: a comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:429-468.

19. Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:27-51.

20. Straus MA, Gozjolko KL. “Intimate terrorism” and gender differences in injury of dating partners by male and female university students. J Fam Violence. 2014;29:51-65.

21. Ferraro KJ, Johnson JM. How women experience battering: the process of victimization. Soc Probl. 1983;30:325-339.

22. Sugg NK, Inui T. Primary care physicians’ response to domestic violence: opening Pandora’s box. JAMA. 1992;267:3157-3160.

23. Morgan KJ, Williamson E, Hester M, et al. Asking men about domestic violence and abuse in a family medicine context: help seeking and views on the general practitioner role. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19:637-642.

24. MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al; McMaster Violence Against Women Research Group. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:530-536.

25. Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC, et al. Identification and management of domestic violence: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:253-263.

26. Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:930-933.

27. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4.

28. Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, et al. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280-295.

29. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, et al. HITS: A short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

30. Peralta RL, Fleming MF. Screening for intimate partner violence in a primary care setting: the validity of “feeling safe at home” and prevalence results. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:525-532.

31. Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, et al. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231-280.

32. Brownridge DA, Taillieu TL, Tyler KA, et al. Pregnancy and intimate partner violence: risk factors, severity, and health effects. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:858-881.

33. Messing JT, Campbell JC, Snider C. Validation and adaptation of the danger assessment-5: a brief intimate partner violence risk assessment. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:3220-3230.

34. Grigsby N, Hartman BR. The Barriers Model: an integrated strategy for intervention with battered women. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1997;34:485-497.

35. Moyers TB, Rollnick S. A motivational interviewing perspective on resistance in psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:185-193.

36. Belfrage H, Strand S, Storey JE, et al. Assessment and management of risk for intimate partner violence by police officers using the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide. Law Hum Behav. 2012;36:60-67.

37. McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, et al. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Publ Health Rep. 2006;121:435-444.

38. Eckhardt CI, Murphy CM, Whitaker DJ, et al. The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:196-231.

39. Trabold N, McMahon J, Alsobrooks S, et al. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions: state of the field and implications for practitioners. Trauma Violence Abuse. January 2018:1524838018767934.

40. Kraanen FL, Vedel E, Scholing A, et al. The comparative effectiveness of Integrated treatment for Substance abuse and Partner violence (I-StoP) and substance abuse treatment alone: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:189.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health problem with considerable harmful health consequences. Decades of research have been dedicated to improving the identification of women in abusive heterosexual relationships and interventions that support healthier outcomes. A result of this work has been the recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV and provided with intervention or referral.1

The problem extends further, however: Epidemiologic studies and comprehensive reviews show: 1) a high rate of IPV victimization among heterosexual men and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual (LGBT) men and women2,3; 2) significant harmful effects on health and greater expectations of prejudice and discrimination among these populations4-6; and 3) evidence that screening and referral for IPV are likely to confer similar benefits for these populations.7 We argue that it is reasonable to ask all patients about abuse in their relationships while the research literature progresses.

We intend this article to serve a number of purposes:

- support national standards for IPV screening of female patients

- highlight the need for piloting universal IPV screening for all patients (ie, male and female, across the lifespan)

- offer recommendations for navigating the process from IPV screening to referral, using insights gained from the substance abuse literature.

We also provide supplemental materials that facilitate establishment of screening and referral protocols for physicians across practice settings.

What is intimate partner violence? How can you identify it?

Intimate partner violence includes physical and sexual violence and nonphysical forms of abuse, such as psychological aggression and emotional abuse, perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner.8 TABLE 19-14 provides definitions for each of these behavior categories and example behaviors. Nearly 25% of women and 20% of men report having experienced physical violence from a romantic partner and even higher rates of nonphysical IPV.15 Consequences of IPV victimization include acute and chronic medical illness, injury, and psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and poor self-esteem.16

Intimate partner violence is heterogeneous, with differences in severity (eg, frequency and intensity of violence) and laterality (ie, is one partner violent? are both partners violent?). A recent comprehensive review of the literature revealed that, for 49.2%-69.7% of partner-violent couples across diverse samples, IPV is perpetrated by both partners.17 Furthermore, this bidirectionality is not due entirely to aggression perpetrated in self-defense; rather, across diverse patient samples, that is the case for fewer than one-quarter of males and no more than approximately one-third of females.18 In the remaining cases, bidirectionality may be attributed to other motivations, such as a maladaptive emotional expression or a means by which to get a partner’s attention.18

Women are disproportionately susceptible to harmful outcomes as a result of severe violence, including physical injury, psychological distress (eg, depression and anxiety), and substance abuse.16,19 Some patients in unidirectionally violent relationships experience severe physical violence that may be, or become, life-threatening (0.4%-2.4% of couples in community samples)20—victimization that is traditionally known as “battering.”21

Continue to: These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

Physicians might have reservations asking about IPV because of 1) concern whether there is sufficient time during an office visit to interview, screen, and refer, 2) feelings of powerlessness to stop violence by or toward a patient, and 3) general discomfort with the topic.22 Additionally, mandated reporting laws regarding IPV vary by state, making it crucial to know one’s own state laws on this issue to protect the safety of the patient and those around them.

Research has shown that some patients prefer that their health care providers ask about relationship violence directly23; others are more willing to acknowledge IPV if asked using a paper-and-pencil measure, rather than face-to-face questions.24 Either way, screening increases the likelihood of engaging the patient in supportive services, thus decreasing the isolation that is typical of abuse.25 Based on this research, screening that utilizes face-valid items embedded within paperwork completed in the waiting room is recommended as an important first step toward identifying and helping patients who are experiencing IPV. Even under these conditions, however, heterosexual men and sexual minorities might be less willing than heterosexual women to admit experiencing IPV.26,27

A brief vignette that depicts how quickly the screening and referral process can be applied is presented in “IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette." The vignette is a de-identified composite of heterosexual men experiencing IPV whom we have counseled.

SIDEBAR

IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette

Physician: Before we wrap up: I noticed on your screening that you have been hurt and threatened a fair amount in the past year. Would it be OK if we spoke about that more?

Patient: My wife is emotional. Sometimes she gets really stressed out and just starts screaming and punching me. That’s just how she is.

Physician: Do you ever feel concerned for your safety?

Patient: Not really. She’s smaller than me and I can generally calm her down. I keep the guns locked up, so she can’t grab those any more. Mostly she just screams at me.

Physician: This may or may not fit with your perception but, based on what you are reporting, your relationship is what is called “at risk”—meaning you are at risk for having your physical or mental health negatively impacted. This actually happens to a lot of men, and there’s a brochure I can give you that has a lot more information about the risks and consequences of being hurt or threatened by a partner. Would you be willing to take a look at it?

Patient: I guess so.

Physician: OK. I’ll have the nurse bring you that brochure, and we can talk more about it next time you come in for an appointment. Would it be OK if we get you back in here 6 months from now?

Patient: Yeah, that could work.

Physician: Great. Let’s do that. Don’t hesitate to give me a call if your situation changes in any way in the meantime.

One model that provides a useful framework for IPV assessment is the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model, which was developed to facilitate assessment of, and referral for, substance abuse—another heavily stigmatized health care problem. The SBIRT approach for substance abuse screening is associated with significant reduction in alcohol and drug abuse 6 months postintervention, as well as improvements in well-being, mental health, and functioning across gender, race and ethnicity, and age.28

IPASSPRT. Inspired by the SBIRT model for substance abuse, we created the Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment, or IPASSPRT (spoken as “i-passport”) project to provide tools that make IPV screening and referral accessible to a range of health care providers. These tools include a script and safety plan that guide providers through screening, safety planning, and referral in a manner that is collaborative and grounded in the spirit of motivational interviewing. We have made these tools available on the Web for ease of distribution (http://bit.ly/ipassprt; open by linking through “IPASSPRT-Script”).

Continue to: The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy...

The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy, but progress through its sections is directed by patient need; most patients will not require that all parts be completed. For example, a patient whose screen for IPV is negative and who feels safe in their relationship does not need assessment beyond page 2; on the other hand, the physician might need more information from a patient who is at greater risk for IPV. This response-based progression through the script makes the screening process dynamic, data-driven, and tailored to the patient’s needs—an approach that aids rapport and optimizes the physician’s limited time during the appointment.

In the sections that follow, we describe key components of this script.

What aggression, if any, is present? From whom? The Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream inventory (HITS) (TABLE 2)29 is a widely used screen for IPV that has been validated for use in family medicine. A 4-item scale asks patients to report how often their partner physically hurts, insults, threatens, and screams at them using a 5-point scale (1 point, “never,” to 5 points, “frequently”). Although a score > 10 is indicative of IPV, item-level analysis is encouraged. Attending to which items the patient acknowledges and how often these behaviors occur yields a richer assessment than a summary score. In regard to simply asking a patient, “Do you feel safe at home?” (sensitivity of this question, 8.8%; specificity, 91.2%), the HITS better detects IPV with male and female patient populations in family practice and emergency care settings (sensitivity, 30%-100%; specificity, 86%-99%).27,30

What contextual factors and related concerns are present? It is important to understand proximal factors that might influence IPV risk to determine what kind of referral or treatment is appropriate—particularly for patients experiencing or engaging in infrequent, noninjurious, and bidirectional forms of IPV. Environmental and contextual stressors, such as financial hardship, unemployment, pregnancy, and discussion of divorce, can increase the risk for IPV.31,32 Situational influences, such as alcohol and drug intoxication, can also increase the risk for IPV. Victims of partner violence are at greater risk for mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, and substance use disorders. Risk goes both ways, however: Mental illness predicts subsequent IPV perpetration or victimization, and vice versa.31

Does the patient feel safe? Assessing the situation. Patient perception of safety in the relationship provides important information about the necessity of referral. Asking a patient if they feel unsafe because of the behavior of a current or former partner sheds light on the need for further safety assessment and immediate connection with appropriate resources.

Continue to: The Danger Assessment-5...

The Danger Assessment-5 (DA-5) (TABLE 333) is a useful 5-item tool for quickly assessing the risk for severe IPV.33 Patients respond to whether:

- the frequency or severity of violence has increased in the past year

- the partner has ever used, or threatened to use, a weapon

- the patient believes the partner is capable of killing her (him)

- the partner has ever tried to choke or strangle her (him)

- the partner is violently and constantly jealous.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses with a high-risk female sample suggested that 3 affirmative responses indicate a high risk for severe IPV and a need for adequate safety planning.

Brief motivational enhancement intervention. There are 3 components to this intervention.

- Assess interest in making changes or seeking help. IPV is paradoxical: Many factors complicate the decision to leave or stay, and patients across the spectrum of victimization might have some motivation to stay with their partner. It is important to assess the patient’s motivation to make changes in their relationship.4,34

- Provide feedback on screening. Sharing the results of screening with patients makes the assessment and referral process collaborative and transparent; collaborative engagement helps patients feel in control and invested in the follow-through.35 In the spirit of this endeavor, physicians are encouraged to refrain from providing raw or total scores from the measures; instead, share the interpretation of those scores, based on the participant’s responses to the screening items, in a matter-of-fact manner. At this point, elicit the patient’s response to this information, listen empathically, and answer questions before proceeding.

Consistent with screening for other serious health problems, we recommend that all patients be provided with information about abuse in romantic relationships. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention has published a useful, easy-to-understand fact sheet (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf) that provides an overview of IPV-related behavior, how it influences health outcomes, who is at risk for IPV, and sources for support.

Continue to: Our IPASSPRT interview script...

Our IPASSPRT interview script (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) outlines how this information can be presented to patients as a typical part of the screening process. Providers are encouraged to share and review the information from the fact sheet with all patients and present it as part of the normal screening process to mitigate the potential for defensiveness on the part of the patient. For patients who screen positive for IPV, it might be important to brainstorm ideas for a safe, secure place to store this fact sheet and other resources from the brief intervention and referral process below (eg, a safety plan and specific referral information) so that the patient can access them quickly and easily, if needed.

For patients who screen negative for IPV, their screen and interview conclude at this point.

- Provide recommendations based on the screen. Evidence suggests that collaborating with the patient on safety planning and referral can increase the likelihood of their engagement.7 Furthermore, failure to tailor the referral to the needs of the patient can be detrimental36—ie, overshooting the level of intervention might decrease the patient’s future treatment-seeking behavior and undermine their internal coping strategies, increasing the likelihood of future victimization. For that reason, we provide the following guidance on navigating the referral process for patients who screen positive for IPV.

Screening-based referral: A delicate and collaborative process

Referral for IPV victimization. Individual counseling, with or without an IPV focus, might be appropriate for patients at lower levels of risk; immediate connection with local IPV resources is strongly encouraged for patients at higher risk. This is a delicate, collaborative process, in which the physician offers recommendations for referral commensurate to the patient’s risk but must, ultimately, respect the patient’s autonomy by identifying referrals that fit the patient’s goals. We encourage providers to provide risk-informed recommendations and to elicit the patient’s thoughts about that information.

Several online resources are available to help physicians locate and connect with IPV-related resources in their community, including the National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence (http://ipvhealth.org/), which provides a step-by-step guide to making such connections. We encourage physicians to develop these collaborative partnerships early to facilitate warm handoffs and increase the likelihood that a patient will follow through with the referral after screening.37

Referral for related concerns. As we’ve noted, IPV has numerous physical and mental health consequences, including depression, low self-esteem, trauma- and non-trauma-related anxiety, and substance abuse. In general, cognitive behavioral therapies appear most efficacious for treating these IPV-related consequences, but evidence is limited that such interventions diminish the likelihood of re-victimization.38 Intervention programs that foster problem-solving, solution-seeking, and cognitive restructuring for self-critical thoughts and misconceptions seem to produce the best physical and mental health outcomes.39 For patients who have a substance use disorder, treatment programs that target substance use have demonstrated a reduction in the rate of IPV recidivism.40 These findings indicate that establishing multiple treatment targets might reduce the risk for future aggression in relationships.

Continue to: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration...

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides a useful online tool (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/) for locating local referrals that address behavioral health and substance-related concerns. The agency also provides a hotline (1-800-662-HELP [4357]) as an alternative resource for information and treatment referrals.

Safety planning can improve outcomes

For a patient who screens above low risk, safety planning with the patient is an important part of improving outcomes and can take several forms. Online resources, such as the Path to Safety interactive Web page (www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/) maintained by The National Domestic Violence Hotline ([800]799-SAFE [7233]), provide information regarding important considerations for safety planning when:

- living with an abusive partner

- children are in the home

- the patient is pregnant

- pets are involved.

The Web site also provides information regarding legal options and resources related to IPV (eg, an order of protection) and steps for improving safety when leaving an abusive relationship. Patients at risk for IPV can explore the online tool and call the hotline.

For physicians who want to engage in provider-assisted safety planning, we’ve provided further guidance in the IPASSPRT screening script and safety plan (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) (TABLE 4).

Goal: Affirm patients’ strengths and reinforce hope

Psychological aggression is the most common form of relationship aggression; repeated denigration might leave a person with little confidence in their ability to change their relationship or seek out identified resources. That’s why it’s useful to inquire—with genuine curiosity—about a time in the past when the patient accomplished something challenging. The physician’s enthusiastic reflection on this achievement can be a means of highlighting the patient’s ability to accomplish a meaningful goal; of reinforcing their hope; and of eliciting important resources within and around the patient that can facilitate action on their safety plan. (See “IPV-related resources for physicians and patients.”)

SIDEBAR

IPV-related resources for physicians and patients

Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment (IPASSPRT) Project

› http://bit.ly/ipassprt

Online resource with tools designed by the authors, including an SBIRT-inspired script and safety plan template for IPV screening, safety planning, and referral

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention

› www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf

Overview of IPV-related behavior, influence on health outcomes, people at risk of IPV, and sources of support, all in a format easily understood by patients

National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence

› http://ipvhealth.org/

Includes guidance on connecting with IPV-related community resources; establishing such connections can facilitate warm handoffs and improve the likelihood that patients will follow through

Path to Safety, a service of The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/

Extensive primer on safety plans for patients intending to stay in (or leave) an abusive relationship; includes important considerations for children, pets, and pregnancy, as well as emotional safety and legal options

The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› (800) 799-SAFE (7233)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

› www.samhsa.gov/sbirt

Learning resources for the SBIRT protocol for substance abuse

› https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/

Search engine and resources for locating local referrals

› (800) 662-HELP (4357)

Hotline for information and assistance with locating local treatment referral

IPV, intimate partner violence; SBIRT, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment.

Continue to: Closing the screen and making a referral

Closing the screen and making a referral

The end of the interview should consist of a summary of topics discussed, including:

- changes that the patient wants to make (if any)

- their stated reasons for making those changes

- the patient’s plan for accomplishing changes.

Physicians should also include their own role in next steps—whether providing a warm handoff to a local IPV referral, agreeing to a follow-up schedule with the patient, or making a call as a mandated reporter. To close out the interview, it is important to affirm respect for the patient’s autonomy in executing the plan.

It’s important to screen all patients—here’s why

A major impetus for this article has been to raise awareness about the need for expanded IPV screening across primary care settings. As mentioned, much of the literature on IPV victimization has focused on women; however, the few epidemiological investigations of victimization rates among men and members of LGBT couples show a high rate of victimization and considerable harmful health outcomes. Driven by stigma surrounding IPV, sex, and sexual minority status, patients might have expectations that they will be judged by a provider or “outed.”

Such barriers can lead many to suffer in silence until the problem can no longer be hidden or the danger becomes more emergent. Compassionate, nonjudgmental screening and collaborative safety planning—such as the approach we describe in this article—help ease the concerns of LGBT victims of IPV and improve the likelihood that conversations you have with them will occur earlier, rather than later, in care.*

Underassessment of IPV (ie, underreporting as well as under-inquiry) because of stigma, misconception, and other factors obscures an accurate estimate of the rate of partner violence and its consequences for all couples. As a consequence, we know little about the dynamics of IPV, best practices for screening, and appropriate referral for couples from these populations. Furthermore, few resources are available to these understudied and underserved groups (eg, shelters for men and for transgender people).

Continue to: Although our immediate approach to IPV screening...

Although our immediate approach to IPV screening, safety planning, and referral with understudied patient populations might be informed by what we have learned from the experiences of heterosexual women in abusive relationships, such a practice is unsustainable. Unless we expand our scope of screening to all patients, it is unlikely that we will develop the evidence base necessary to 1) warrant stronger IPV screening recommendations for patient groups apart from women of childbearing age, let alone 2) demonstrate the need for additional community resources, and 3) provide comprehensive care in family practice of comparable quality.

The benefits of screening go beyond the individual patient

Screening for violence in the relationship does not take long; the value of asking about its presence in a relationship might offer benefits beyond the individual patient by raising awareness and providing the field of study with more data to increase attention and resources for under-researched and underserved populations. Screening might also combat the stigma that perpetuates the silence of many who deserve access to care.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel G. Sprunger, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 260 Stetson St, Suite 3200, Cincinnati OH 45219; joel.sprunger@UC.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jeffrey M. Girard, PhD, and Daniel C. Williams, PhD, for their input on the design and content, respectively, of the IPASSPRT screening materials; the authors of the DA-5 and the HITS screening tools, particularly Jacquelyn Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN, and Kevin Sherin, MD, MPH, MBA, respectively, for permission to include these measures in this article and for their support of its goals; and The Journal of Family Practice’s peer reviewers for their thoughtful feedback throughout the prepublication process.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health problem with considerable harmful health consequences. Decades of research have been dedicated to improving the identification of women in abusive heterosexual relationships and interventions that support healthier outcomes. A result of this work has been the recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV and provided with intervention or referral.1

The problem extends further, however: Epidemiologic studies and comprehensive reviews show: 1) a high rate of IPV victimization among heterosexual men and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual (LGBT) men and women2,3; 2) significant harmful effects on health and greater expectations of prejudice and discrimination among these populations4-6; and 3) evidence that screening and referral for IPV are likely to confer similar benefits for these populations.7 We argue that it is reasonable to ask all patients about abuse in their relationships while the research literature progresses.

We intend this article to serve a number of purposes:

- support national standards for IPV screening of female patients

- highlight the need for piloting universal IPV screening for all patients (ie, male and female, across the lifespan)

- offer recommendations for navigating the process from IPV screening to referral, using insights gained from the substance abuse literature.

We also provide supplemental materials that facilitate establishment of screening and referral protocols for physicians across practice settings.

What is intimate partner violence? How can you identify it?

Intimate partner violence includes physical and sexual violence and nonphysical forms of abuse, such as psychological aggression and emotional abuse, perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner.8 TABLE 19-14 provides definitions for each of these behavior categories and example behaviors. Nearly 25% of women and 20% of men report having experienced physical violence from a romantic partner and even higher rates of nonphysical IPV.15 Consequences of IPV victimization include acute and chronic medical illness, injury, and psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and poor self-esteem.16

Intimate partner violence is heterogeneous, with differences in severity (eg, frequency and intensity of violence) and laterality (ie, is one partner violent? are both partners violent?). A recent comprehensive review of the literature revealed that, for 49.2%-69.7% of partner-violent couples across diverse samples, IPV is perpetrated by both partners.17 Furthermore, this bidirectionality is not due entirely to aggression perpetrated in self-defense; rather, across diverse patient samples, that is the case for fewer than one-quarter of males and no more than approximately one-third of females.18 In the remaining cases, bidirectionality may be attributed to other motivations, such as a maladaptive emotional expression or a means by which to get a partner’s attention.18

Women are disproportionately susceptible to harmful outcomes as a result of severe violence, including physical injury, psychological distress (eg, depression and anxiety), and substance abuse.16,19 Some patients in unidirectionally violent relationships experience severe physical violence that may be, or become, life-threatening (0.4%-2.4% of couples in community samples)20—victimization that is traditionally known as “battering.”21

Continue to: These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

These tools can facilitate screening for IPV

Physicians might have reservations asking about IPV because of 1) concern whether there is sufficient time during an office visit to interview, screen, and refer, 2) feelings of powerlessness to stop violence by or toward a patient, and 3) general discomfort with the topic.22 Additionally, mandated reporting laws regarding IPV vary by state, making it crucial to know one’s own state laws on this issue to protect the safety of the patient and those around them.

Research has shown that some patients prefer that their health care providers ask about relationship violence directly23; others are more willing to acknowledge IPV if asked using a paper-and-pencil measure, rather than face-to-face questions.24 Either way, screening increases the likelihood of engaging the patient in supportive services, thus decreasing the isolation that is typical of abuse.25 Based on this research, screening that utilizes face-valid items embedded within paperwork completed in the waiting room is recommended as an important first step toward identifying and helping patients who are experiencing IPV. Even under these conditions, however, heterosexual men and sexual minorities might be less willing than heterosexual women to admit experiencing IPV.26,27

A brief vignette that depicts how quickly the screening and referral process can be applied is presented in “IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette." The vignette is a de-identified composite of heterosexual men experiencing IPV whom we have counseled.

SIDEBAR

IPV screening and referral: A real-world vignette

Physician: Before we wrap up: I noticed on your screening that you have been hurt and threatened a fair amount in the past year. Would it be OK if we spoke about that more?

Patient: My wife is emotional. Sometimes she gets really stressed out and just starts screaming and punching me. That’s just how she is.

Physician: Do you ever feel concerned for your safety?

Patient: Not really. She’s smaller than me and I can generally calm her down. I keep the guns locked up, so she can’t grab those any more. Mostly she just screams at me.

Physician: This may or may not fit with your perception but, based on what you are reporting, your relationship is what is called “at risk”—meaning you are at risk for having your physical or mental health negatively impacted. This actually happens to a lot of men, and there’s a brochure I can give you that has a lot more information about the risks and consequences of being hurt or threatened by a partner. Would you be willing to take a look at it?

Patient: I guess so.

Physician: OK. I’ll have the nurse bring you that brochure, and we can talk more about it next time you come in for an appointment. Would it be OK if we get you back in here 6 months from now?

Patient: Yeah, that could work.

Physician: Great. Let’s do that. Don’t hesitate to give me a call if your situation changes in any way in the meantime.

One model that provides a useful framework for IPV assessment is the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model, which was developed to facilitate assessment of, and referral for, substance abuse—another heavily stigmatized health care problem. The SBIRT approach for substance abuse screening is associated with significant reduction in alcohol and drug abuse 6 months postintervention, as well as improvements in well-being, mental health, and functioning across gender, race and ethnicity, and age.28

IPASSPRT. Inspired by the SBIRT model for substance abuse, we created the Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment, or IPASSPRT (spoken as “i-passport”) project to provide tools that make IPV screening and referral accessible to a range of health care providers. These tools include a script and safety plan that guide providers through screening, safety planning, and referral in a manner that is collaborative and grounded in the spirit of motivational interviewing. We have made these tools available on the Web for ease of distribution (http://bit.ly/ipassprt; open by linking through “IPASSPRT-Script”).

Continue to: The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy...

The IPASSPRT script appears lengthy, but progress through its sections is directed by patient need; most patients will not require that all parts be completed. For example, a patient whose screen for IPV is negative and who feels safe in their relationship does not need assessment beyond page 2; on the other hand, the physician might need more information from a patient who is at greater risk for IPV. This response-based progression through the script makes the screening process dynamic, data-driven, and tailored to the patient’s needs—an approach that aids rapport and optimizes the physician’s limited time during the appointment.

In the sections that follow, we describe key components of this script.

What aggression, if any, is present? From whom? The Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream inventory (HITS) (TABLE 2)29 is a widely used screen for IPV that has been validated for use in family medicine. A 4-item scale asks patients to report how often their partner physically hurts, insults, threatens, and screams at them using a 5-point scale (1 point, “never,” to 5 points, “frequently”). Although a score > 10 is indicative of IPV, item-level analysis is encouraged. Attending to which items the patient acknowledges and how often these behaviors occur yields a richer assessment than a summary score. In regard to simply asking a patient, “Do you feel safe at home?” (sensitivity of this question, 8.8%; specificity, 91.2%), the HITS better detects IPV with male and female patient populations in family practice and emergency care settings (sensitivity, 30%-100%; specificity, 86%-99%).27,30

What contextual factors and related concerns are present? It is important to understand proximal factors that might influence IPV risk to determine what kind of referral or treatment is appropriate—particularly for patients experiencing or engaging in infrequent, noninjurious, and bidirectional forms of IPV. Environmental and contextual stressors, such as financial hardship, unemployment, pregnancy, and discussion of divorce, can increase the risk for IPV.31,32 Situational influences, such as alcohol and drug intoxication, can also increase the risk for IPV. Victims of partner violence are at greater risk for mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, and substance use disorders. Risk goes both ways, however: Mental illness predicts subsequent IPV perpetration or victimization, and vice versa.31

Does the patient feel safe? Assessing the situation. Patient perception of safety in the relationship provides important information about the necessity of referral. Asking a patient if they feel unsafe because of the behavior of a current or former partner sheds light on the need for further safety assessment and immediate connection with appropriate resources.

Continue to: The Danger Assessment-5...

The Danger Assessment-5 (DA-5) (TABLE 333) is a useful 5-item tool for quickly assessing the risk for severe IPV.33 Patients respond to whether:

- the frequency or severity of violence has increased in the past year

- the partner has ever used, or threatened to use, a weapon

- the patient believes the partner is capable of killing her (him)

- the partner has ever tried to choke or strangle her (him)

- the partner is violently and constantly jealous.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses with a high-risk female sample suggested that 3 affirmative responses indicate a high risk for severe IPV and a need for adequate safety planning.

Brief motivational enhancement intervention. There are 3 components to this intervention.

- Assess interest in making changes or seeking help. IPV is paradoxical: Many factors complicate the decision to leave or stay, and patients across the spectrum of victimization might have some motivation to stay with their partner. It is important to assess the patient’s motivation to make changes in their relationship.4,34

- Provide feedback on screening. Sharing the results of screening with patients makes the assessment and referral process collaborative and transparent; collaborative engagement helps patients feel in control and invested in the follow-through.35 In the spirit of this endeavor, physicians are encouraged to refrain from providing raw or total scores from the measures; instead, share the interpretation of those scores, based on the participant’s responses to the screening items, in a matter-of-fact manner. At this point, elicit the patient’s response to this information, listen empathically, and answer questions before proceeding.

Consistent with screening for other serious health problems, we recommend that all patients be provided with information about abuse in romantic relationships. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention has published a useful, easy-to-understand fact sheet (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf) that provides an overview of IPV-related behavior, how it influences health outcomes, who is at risk for IPV, and sources for support.

Continue to: Our IPASSPRT interview script...

Our IPASSPRT interview script (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) outlines how this information can be presented to patients as a typical part of the screening process. Providers are encouraged to share and review the information from the fact sheet with all patients and present it as part of the normal screening process to mitigate the potential for defensiveness on the part of the patient. For patients who screen positive for IPV, it might be important to brainstorm ideas for a safe, secure place to store this fact sheet and other resources from the brief intervention and referral process below (eg, a safety plan and specific referral information) so that the patient can access them quickly and easily, if needed.

For patients who screen negative for IPV, their screen and interview conclude at this point.

- Provide recommendations based on the screen. Evidence suggests that collaborating with the patient on safety planning and referral can increase the likelihood of their engagement.7 Furthermore, failure to tailor the referral to the needs of the patient can be detrimental36—ie, overshooting the level of intervention might decrease the patient’s future treatment-seeking behavior and undermine their internal coping strategies, increasing the likelihood of future victimization. For that reason, we provide the following guidance on navigating the referral process for patients who screen positive for IPV.

Screening-based referral: A delicate and collaborative process

Referral for IPV victimization. Individual counseling, with or without an IPV focus, might be appropriate for patients at lower levels of risk; immediate connection with local IPV resources is strongly encouraged for patients at higher risk. This is a delicate, collaborative process, in which the physician offers recommendations for referral commensurate to the patient’s risk but must, ultimately, respect the patient’s autonomy by identifying referrals that fit the patient’s goals. We encourage providers to provide risk-informed recommendations and to elicit the patient’s thoughts about that information.

Several online resources are available to help physicians locate and connect with IPV-related resources in their community, including the National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence (http://ipvhealth.org/), which provides a step-by-step guide to making such connections. We encourage physicians to develop these collaborative partnerships early to facilitate warm handoffs and increase the likelihood that a patient will follow through with the referral after screening.37

Referral for related concerns. As we’ve noted, IPV has numerous physical and mental health consequences, including depression, low self-esteem, trauma- and non-trauma-related anxiety, and substance abuse. In general, cognitive behavioral therapies appear most efficacious for treating these IPV-related consequences, but evidence is limited that such interventions diminish the likelihood of re-victimization.38 Intervention programs that foster problem-solving, solution-seeking, and cognitive restructuring for self-critical thoughts and misconceptions seem to produce the best physical and mental health outcomes.39 For patients who have a substance use disorder, treatment programs that target substance use have demonstrated a reduction in the rate of IPV recidivism.40 These findings indicate that establishing multiple treatment targets might reduce the risk for future aggression in relationships.

Continue to: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration...

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides a useful online tool (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/) for locating local referrals that address behavioral health and substance-related concerns. The agency also provides a hotline (1-800-662-HELP [4357]) as an alternative resource for information and treatment referrals.

Safety planning can improve outcomes

For a patient who screens above low risk, safety planning with the patient is an important part of improving outcomes and can take several forms. Online resources, such as the Path to Safety interactive Web page (www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/) maintained by The National Domestic Violence Hotline ([800]799-SAFE [7233]), provide information regarding important considerations for safety planning when:

- living with an abusive partner

- children are in the home

- the patient is pregnant

- pets are involved.

The Web site also provides information regarding legal options and resources related to IPV (eg, an order of protection) and steps for improving safety when leaving an abusive relationship. Patients at risk for IPV can explore the online tool and call the hotline.

For physicians who want to engage in provider-assisted safety planning, we’ve provided further guidance in the IPASSPRT screening script and safety plan (http://bit.ly/ipassprt) (TABLE 4).

Goal: Affirm patients’ strengths and reinforce hope

Psychological aggression is the most common form of relationship aggression; repeated denigration might leave a person with little confidence in their ability to change their relationship or seek out identified resources. That’s why it’s useful to inquire—with genuine curiosity—about a time in the past when the patient accomplished something challenging. The physician’s enthusiastic reflection on this achievement can be a means of highlighting the patient’s ability to accomplish a meaningful goal; of reinforcing their hope; and of eliciting important resources within and around the patient that can facilitate action on their safety plan. (See “IPV-related resources for physicians and patients.”)

SIDEBAR

IPV-related resources for physicians and patients

Intimate Partner Aggression Screening, Safety Planning, and Referral to Treatment (IPASSPRT) Project

› http://bit.ly/ipassprt

Online resource with tools designed by the authors, including an SBIRT-inspired script and safety plan template for IPV screening, safety planning, and referral

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Violence Prevention

› www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet.pdf

Overview of IPV-related behavior, influence on health outcomes, people at risk of IPV, and sources of support, all in a format easily understood by patients

National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence

› http://ipvhealth.org/

Includes guidance on connecting with IPV-related community resources; establishing such connections can facilitate warm handoffs and improve the likelihood that patients will follow through

Path to Safety, a service of The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› www.thehotline.org/help/path-to-safety/

Extensive primer on safety plans for patients intending to stay in (or leave) an abusive relationship; includes important considerations for children, pets, and pregnancy, as well as emotional safety and legal options

The National Domestic Violence Hotline

› (800) 799-SAFE (7233)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

› www.samhsa.gov/sbirt

Learning resources for the SBIRT protocol for substance abuse

› https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/

Search engine and resources for locating local referrals

› (800) 662-HELP (4357)

Hotline for information and assistance with locating local treatment referral

IPV, intimate partner violence; SBIRT, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment.

Continue to: Closing the screen and making a referral

Closing the screen and making a referral

The end of the interview should consist of a summary of topics discussed, including:

- changes that the patient wants to make (if any)

- their stated reasons for making those changes

- the patient’s plan for accomplishing changes.

Physicians should also include their own role in next steps—whether providing a warm handoff to a local IPV referral, agreeing to a follow-up schedule with the patient, or making a call as a mandated reporter. To close out the interview, it is important to affirm respect for the patient’s autonomy in executing the plan.

It’s important to screen all patients—here’s why

A major impetus for this article has been to raise awareness about the need for expanded IPV screening across primary care settings. As mentioned, much of the literature on IPV victimization has focused on women; however, the few epidemiological investigations of victimization rates among men and members of LGBT couples show a high rate of victimization and considerable harmful health outcomes. Driven by stigma surrounding IPV, sex, and sexual minority status, patients might have expectations that they will be judged by a provider or “outed.”

Such barriers can lead many to suffer in silence until the problem can no longer be hidden or the danger becomes more emergent. Compassionate, nonjudgmental screening and collaborative safety planning—such as the approach we describe in this article—help ease the concerns of LGBT victims of IPV and improve the likelihood that conversations you have with them will occur earlier, rather than later, in care.*