User login

In the 1970s and early 1980s, population-based screening mammography was studied in numerous randomized control trials (RCTs), with the primary outcome of reduced breast cancer mortality. Although technology and the sensitivity of mammography in the 1980s was somewhat rudimentary compared with current screening, a meta-analysis of these RCTs demonstrated a clear mortality benefit for screening mammography.1 As a result, widespread population-based mammography was introduced in the mid-1980s in the United States and has become a standard for breast cancer screening.

Since that time, few RCTs of screening mammography versus observation have been conducted because of the ethical challenges of entering women into such studies as well as the difficulty and expense of long-term follow-up to measure the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality. Without ongoing RCTs of mammography, retrospective, observational, and computer simulation trials of the efficacy and harms of screening mammography have been conducted using proxy measures of mortality (such as stage at diagnosis), and some have questioned the overall benefit of screening mammography.2,3

To further complicate this controversy, some national guidelines have recommended against routinely recommending screening mammography for women aged 40 to 49 based on concerns that the harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies, overdiagnosis) exceed the potential benefits (earlier diagnosis, possible decrease in needed treatments, reduced breast cancer mortality).4 This has resulted in a confusing morass of national recommendations with uncertainty regarding the question of whether to routinely offer screening mammography for women in their 40s at average risk for breast cancer.4-6

Recently, to address this question Duffy and colleagues conducted a large RCT of women in their 40s to evaluate the long-term effect of mammography on breast cancer mortality.7 Here, I review the study in depth and offer some guidance to clinicians and women struggling with screening decisions.

Breast cancer mortality significantly lower in the screening group

The RCT, known as the UK Age trial, was conducted in England, Wales, and Scotland and enrolled 160,921 women from 1990 through 1997.7 Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to observation or annual screening mammogram beginning at age 39–41 until age 48. (In the United Kingdom, all women are screened starting at age 50.) Study enrollees were followed for a median of 22.8 years, and the primary outcome was breast cancer mortality.

The study results showed a 25% relative risk (RR) reduction in breast cancer mortality at 10 years of follow-up in the mammography group compared with the unscreened women (83 breast cancer deaths in the mammography group vs 219 in the observation group [RR, 0.75; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.58–0.97; P = .029]). Based on the prevalence of breast cancer in women in their 40s, this 25% relative risk reduction translates into approximately 1 less death per 1,000 women who undergo routine screening in their 40s.

While there was no additional significant mortality reduction beyond 10 years of follow-up, as noted mammography is offered routinely starting at age 50 to all women in the United Kingdom. The authors concluded that “reducing the lower age limit for screening from 50 to 40 years [of age] could potentially reduce breast cancer mortality.”

Was overdiagnosis a concern? Another finding in this trial was related to overdiagnosis of breast cancer in the screened group. Overdiagnosis refers to mammographic-only diagnosis (that is, no clinical findings) of nonaggressive breast cancer, which would remain indolent and not harm the patient. The study results demonstrated essentially no overdiagnosis in women screened at age 40 compared with the unscreened group.

Continue to: Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths...

Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths

The UK Age trial’s primary strength is its study design: a large population-based RCT that included diverse participants with the critical study outcome for cancer screening (mortality). The study’s long-term follow-up is another key strength, since breast cancer mortality typically occurs 7 to 10 years after diagnosis. In addition, results were available for 99.9% of the women enrolled in the trial (that is, only 0.1% of women were lost to follow-up). Interestingly, the demonstrated mortality reduction with screening mammography for women in their 40s validates the mortality benefit demonstrated in other large RCTs of women in their 40s.1

Another strong point is that the study addresses the issue of whether screening women in their 40s results in overdiagnosis compared with women who start screening in their 50s. Further, this study validates a prior observational study that mammographic findings of nonprogressive cancers do not disappear, so nonaggressive cancers that present on mammography in women in their 40s still would be detected when women start screening in their 50s.8

Study limitations should be noted

The study has several limitations. For example, significant improvements have been made in breast cancer treatments that may mitigate against the positive impact of screening mammography. The impact of changed breast cancer management over the past 20 years could not be addressed with this study’s design since women would have been treated in the 1990s. In addition, substantial improvements have occurred in breast cancer screening standards (2 views vs the single view used in the study) and technology since the 1990s. Current mammography includes nearly uniform use of either digital mammography (DM) or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), both of which improve breast cancer detection for women in their 40s compared with the older film-screen technology. In addition, DBT reduces false-positive results by approximately 40%, resulting in fewer callbacks and biopsies. While improved cancer detection and reduced false-positive results are seen with DM and DBT, whether these technology improvements result in improved breast cancer mortality has not yet been sufficiently studied.

Perhaps the most important limitation in this study is that the women did not undergo routine risk assessment before trial entry to assure that they all were at “average risk.” As a result, both high- and average-risk women would have been included in this population-based trial. Without risk stratification, it remains uncertain whether the reduction in breast cancer mortality disproportionately exists within a high-risk subgroup (such as breast cancer gene mutation carriers).

Finally, the cost efficacy of routine screening mammography for women in their 40s was not evaluated in this study.

The UK Age trial in perspective

The good news is that there is the clear evidence that breast cancer mortality rates (deaths per 100,000) have decreased by about 40% over the past 50 years, likely due to improvements in breast cancer treatment and routine screening mammography.9 Breast cancer mortality reduction is particularly important because breast cancer remains the most common cancer and is the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States. In the past decade, considerable debate has arisen arguing whether this reduction in breast cancer mortality is due to improved treatments, routine screening mammography, or both. Authors of a retrospective trial in Australia, recently reviewed in OBG Management, suggested that the majority of improvement is due to improvements in treatment.3,10 However, as the authors pointed out, due to the trial’s retrospective design, causality only can be inferred. The current UK Age trial does add to the numerous prospective trials demonstrating mortality benefit for mammography in women in their 40s.11

What remains a challenge for clinicians, and for women struggling with the mammography question, is the absence of risk assessment in these long-term RCT trials as well as in the large retrospective database studies. Without risk stratification, these studies treated all the study population as “average risk.” Because breast cancer risk assessment is sporadically performed in clinical practice and there are no published RCTs of screening mammography in risk-assessed “average risk” women in their 40s, it remains uncertain whether the women benefiting from screening in their 40s are in a high-risk group or whether women of average risk in this age group also are benefiting from routine screening mammography.

Continue to: What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice...

What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice

It is not time to abandon screening mammography for all women in their 40s. Rather, routine risk assessment should be performed using one of many available validated or widely tested tools, a recommendation supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the US Preventive Services Task Force.5,6,12

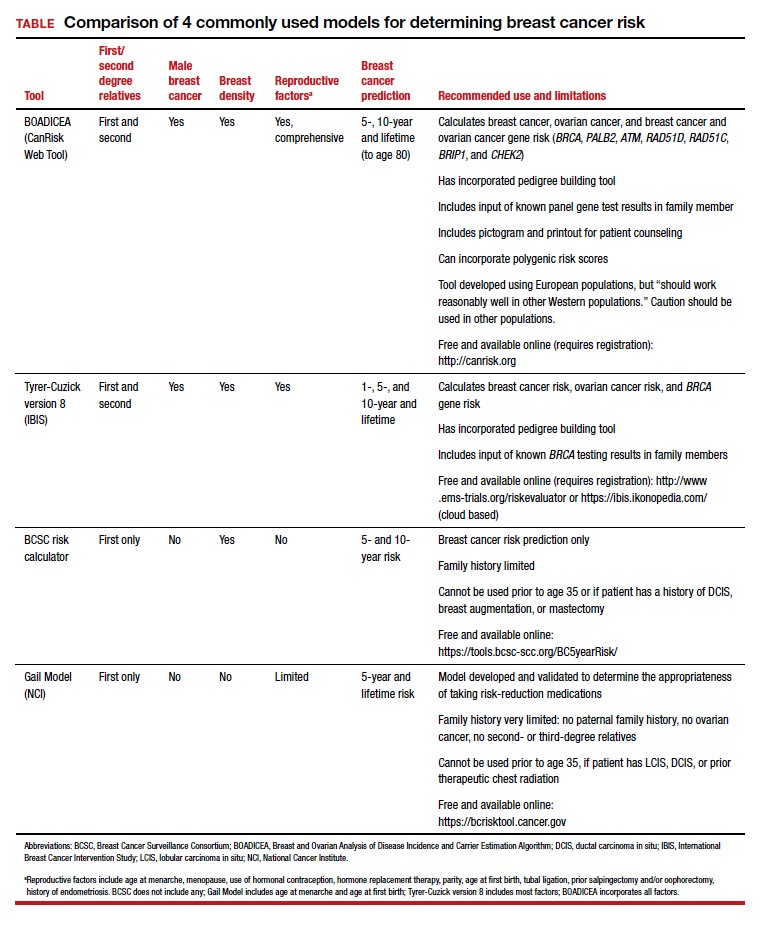

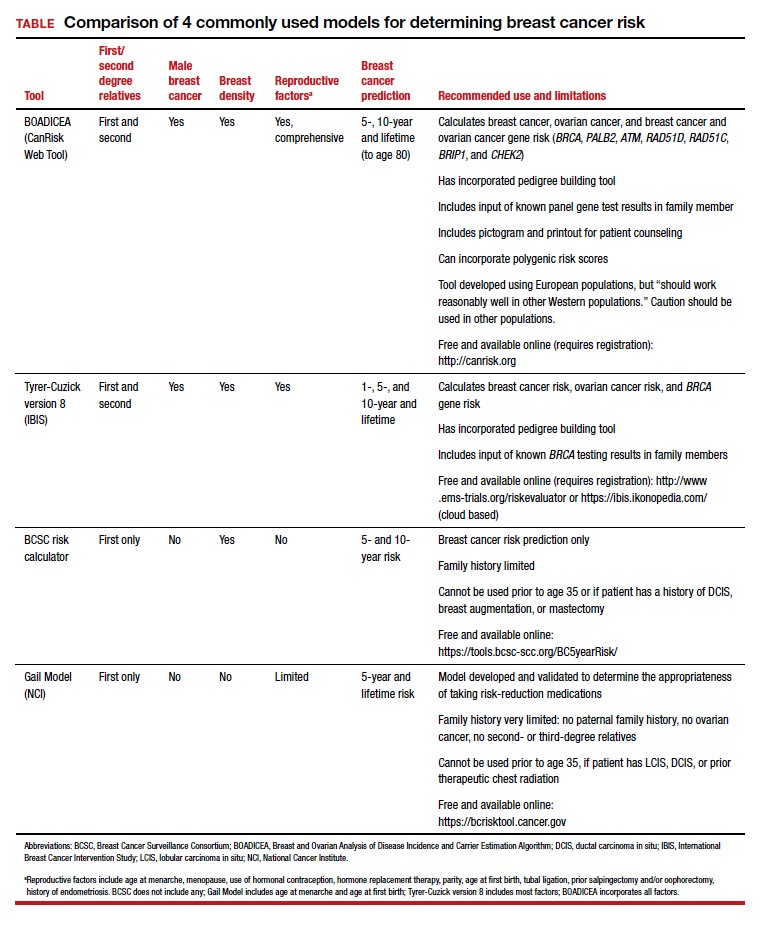

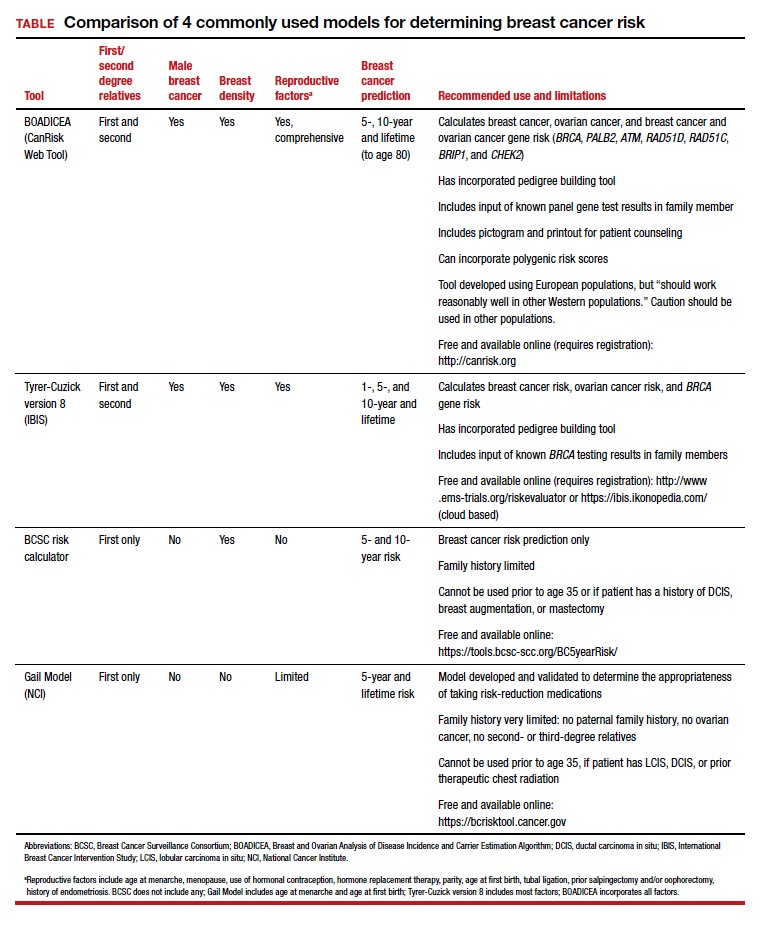

Ideally, these tools can be incorporated into an electronic health record and prepopulated using already available patient data (such as age, reproductive risk factors, current medications, breast density if available, and family history). Prepopulating available data into breast cancer risk calculators would allow clinicians to spend time on counseling women regarding breast cancer risk and appropriate screening methods. The TABLE provides a summary of useful breast cancer risk calculators and includes comments about their utility and significant limitations and benefits. In addition to breast cancer risk, the more comprehensive risk calculators (Tyrer-Cuzick and BOADICEA) allow calculation of ovarian cancer risk and gene mutation risk.

Routinely performing breast cancer risk assessment can guide discussions of screening mammography and can provide data for conducting a more individualized discussion on cancer genetic counseling and testing, risk reduction methods in high-risk women, and possible use of intensive breast cancer screening tools in identified high-risk women.

Ultimately, debating the question of whether all women should have routine breast cancer screening in their 40s should be passé. Ideally, all women should undergo breast cancer risk assessment in their 20s. Risk assessment results can then be used to guide the discussion of multiple potential interventions for women in their 40s (or earlier if appropriate), including routine screening mammography, cancer genetic counseling and testing in appropriate individuals, and intervention for women who are identified at high risk.

Absent breast cancer risk assessment, screening mammography still should be offered to women in their 40s, and the decision to proceed should be based on a discussion of risks, benefits, and the value the patient places on these factors.●

- Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, et al. Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:244-255.

- Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998-2005.

- Burton R, Stevenson C. Assessment of breast cancer mortality trends associated with mammographic screening and adjuvant therapy from 1986 to 2013 in the state of Victoria, Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208249-e.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Humphrey L, et al. A systematic review to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Evidence syntheses No. 124. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05201-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1362-1389.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1-e16.

- Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H, et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1165-1172.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, et al. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:863-867.

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438-451.

- Kaunitz AM. How effective is screening mammography for preventing breast cancer mortality? OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):17,49.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314:1599-1614.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, population-based screening mammography was studied in numerous randomized control trials (RCTs), with the primary outcome of reduced breast cancer mortality. Although technology and the sensitivity of mammography in the 1980s was somewhat rudimentary compared with current screening, a meta-analysis of these RCTs demonstrated a clear mortality benefit for screening mammography.1 As a result, widespread population-based mammography was introduced in the mid-1980s in the United States and has become a standard for breast cancer screening.

Since that time, few RCTs of screening mammography versus observation have been conducted because of the ethical challenges of entering women into such studies as well as the difficulty and expense of long-term follow-up to measure the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality. Without ongoing RCTs of mammography, retrospective, observational, and computer simulation trials of the efficacy and harms of screening mammography have been conducted using proxy measures of mortality (such as stage at diagnosis), and some have questioned the overall benefit of screening mammography.2,3

To further complicate this controversy, some national guidelines have recommended against routinely recommending screening mammography for women aged 40 to 49 based on concerns that the harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies, overdiagnosis) exceed the potential benefits (earlier diagnosis, possible decrease in needed treatments, reduced breast cancer mortality).4 This has resulted in a confusing morass of national recommendations with uncertainty regarding the question of whether to routinely offer screening mammography for women in their 40s at average risk for breast cancer.4-6

Recently, to address this question Duffy and colleagues conducted a large RCT of women in their 40s to evaluate the long-term effect of mammography on breast cancer mortality.7 Here, I review the study in depth and offer some guidance to clinicians and women struggling with screening decisions.

Breast cancer mortality significantly lower in the screening group

The RCT, known as the UK Age trial, was conducted in England, Wales, and Scotland and enrolled 160,921 women from 1990 through 1997.7 Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to observation or annual screening mammogram beginning at age 39–41 until age 48. (In the United Kingdom, all women are screened starting at age 50.) Study enrollees were followed for a median of 22.8 years, and the primary outcome was breast cancer mortality.

The study results showed a 25% relative risk (RR) reduction in breast cancer mortality at 10 years of follow-up in the mammography group compared with the unscreened women (83 breast cancer deaths in the mammography group vs 219 in the observation group [RR, 0.75; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.58–0.97; P = .029]). Based on the prevalence of breast cancer in women in their 40s, this 25% relative risk reduction translates into approximately 1 less death per 1,000 women who undergo routine screening in their 40s.

While there was no additional significant mortality reduction beyond 10 years of follow-up, as noted mammography is offered routinely starting at age 50 to all women in the United Kingdom. The authors concluded that “reducing the lower age limit for screening from 50 to 40 years [of age] could potentially reduce breast cancer mortality.”

Was overdiagnosis a concern? Another finding in this trial was related to overdiagnosis of breast cancer in the screened group. Overdiagnosis refers to mammographic-only diagnosis (that is, no clinical findings) of nonaggressive breast cancer, which would remain indolent and not harm the patient. The study results demonstrated essentially no overdiagnosis in women screened at age 40 compared with the unscreened group.

Continue to: Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths...

Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths

The UK Age trial’s primary strength is its study design: a large population-based RCT that included diverse participants with the critical study outcome for cancer screening (mortality). The study’s long-term follow-up is another key strength, since breast cancer mortality typically occurs 7 to 10 years after diagnosis. In addition, results were available for 99.9% of the women enrolled in the trial (that is, only 0.1% of women were lost to follow-up). Interestingly, the demonstrated mortality reduction with screening mammography for women in their 40s validates the mortality benefit demonstrated in other large RCTs of women in their 40s.1

Another strong point is that the study addresses the issue of whether screening women in their 40s results in overdiagnosis compared with women who start screening in their 50s. Further, this study validates a prior observational study that mammographic findings of nonprogressive cancers do not disappear, so nonaggressive cancers that present on mammography in women in their 40s still would be detected when women start screening in their 50s.8

Study limitations should be noted

The study has several limitations. For example, significant improvements have been made in breast cancer treatments that may mitigate against the positive impact of screening mammography. The impact of changed breast cancer management over the past 20 years could not be addressed with this study’s design since women would have been treated in the 1990s. In addition, substantial improvements have occurred in breast cancer screening standards (2 views vs the single view used in the study) and technology since the 1990s. Current mammography includes nearly uniform use of either digital mammography (DM) or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), both of which improve breast cancer detection for women in their 40s compared with the older film-screen technology. In addition, DBT reduces false-positive results by approximately 40%, resulting in fewer callbacks and biopsies. While improved cancer detection and reduced false-positive results are seen with DM and DBT, whether these technology improvements result in improved breast cancer mortality has not yet been sufficiently studied.

Perhaps the most important limitation in this study is that the women did not undergo routine risk assessment before trial entry to assure that they all were at “average risk.” As a result, both high- and average-risk women would have been included in this population-based trial. Without risk stratification, it remains uncertain whether the reduction in breast cancer mortality disproportionately exists within a high-risk subgroup (such as breast cancer gene mutation carriers).

Finally, the cost efficacy of routine screening mammography for women in their 40s was not evaluated in this study.

The UK Age trial in perspective

The good news is that there is the clear evidence that breast cancer mortality rates (deaths per 100,000) have decreased by about 40% over the past 50 years, likely due to improvements in breast cancer treatment and routine screening mammography.9 Breast cancer mortality reduction is particularly important because breast cancer remains the most common cancer and is the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States. In the past decade, considerable debate has arisen arguing whether this reduction in breast cancer mortality is due to improved treatments, routine screening mammography, or both. Authors of a retrospective trial in Australia, recently reviewed in OBG Management, suggested that the majority of improvement is due to improvements in treatment.3,10 However, as the authors pointed out, due to the trial’s retrospective design, causality only can be inferred. The current UK Age trial does add to the numerous prospective trials demonstrating mortality benefit for mammography in women in their 40s.11

What remains a challenge for clinicians, and for women struggling with the mammography question, is the absence of risk assessment in these long-term RCT trials as well as in the large retrospective database studies. Without risk stratification, these studies treated all the study population as “average risk.” Because breast cancer risk assessment is sporadically performed in clinical practice and there are no published RCTs of screening mammography in risk-assessed “average risk” women in their 40s, it remains uncertain whether the women benefiting from screening in their 40s are in a high-risk group or whether women of average risk in this age group also are benefiting from routine screening mammography.

Continue to: What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice...

What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice

It is not time to abandon screening mammography for all women in their 40s. Rather, routine risk assessment should be performed using one of many available validated or widely tested tools, a recommendation supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the US Preventive Services Task Force.5,6,12

Ideally, these tools can be incorporated into an electronic health record and prepopulated using already available patient data (such as age, reproductive risk factors, current medications, breast density if available, and family history). Prepopulating available data into breast cancer risk calculators would allow clinicians to spend time on counseling women regarding breast cancer risk and appropriate screening methods. The TABLE provides a summary of useful breast cancer risk calculators and includes comments about their utility and significant limitations and benefits. In addition to breast cancer risk, the more comprehensive risk calculators (Tyrer-Cuzick and BOADICEA) allow calculation of ovarian cancer risk and gene mutation risk.

Routinely performing breast cancer risk assessment can guide discussions of screening mammography and can provide data for conducting a more individualized discussion on cancer genetic counseling and testing, risk reduction methods in high-risk women, and possible use of intensive breast cancer screening tools in identified high-risk women.

Ultimately, debating the question of whether all women should have routine breast cancer screening in their 40s should be passé. Ideally, all women should undergo breast cancer risk assessment in their 20s. Risk assessment results can then be used to guide the discussion of multiple potential interventions for women in their 40s (or earlier if appropriate), including routine screening mammography, cancer genetic counseling and testing in appropriate individuals, and intervention for women who are identified at high risk.

Absent breast cancer risk assessment, screening mammography still should be offered to women in their 40s, and the decision to proceed should be based on a discussion of risks, benefits, and the value the patient places on these factors.●

In the 1970s and early 1980s, population-based screening mammography was studied in numerous randomized control trials (RCTs), with the primary outcome of reduced breast cancer mortality. Although technology and the sensitivity of mammography in the 1980s was somewhat rudimentary compared with current screening, a meta-analysis of these RCTs demonstrated a clear mortality benefit for screening mammography.1 As a result, widespread population-based mammography was introduced in the mid-1980s in the United States and has become a standard for breast cancer screening.

Since that time, few RCTs of screening mammography versus observation have been conducted because of the ethical challenges of entering women into such studies as well as the difficulty and expense of long-term follow-up to measure the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality. Without ongoing RCTs of mammography, retrospective, observational, and computer simulation trials of the efficacy and harms of screening mammography have been conducted using proxy measures of mortality (such as stage at diagnosis), and some have questioned the overall benefit of screening mammography.2,3

To further complicate this controversy, some national guidelines have recommended against routinely recommending screening mammography for women aged 40 to 49 based on concerns that the harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies, overdiagnosis) exceed the potential benefits (earlier diagnosis, possible decrease in needed treatments, reduced breast cancer mortality).4 This has resulted in a confusing morass of national recommendations with uncertainty regarding the question of whether to routinely offer screening mammography for women in their 40s at average risk for breast cancer.4-6

Recently, to address this question Duffy and colleagues conducted a large RCT of women in their 40s to evaluate the long-term effect of mammography on breast cancer mortality.7 Here, I review the study in depth and offer some guidance to clinicians and women struggling with screening decisions.

Breast cancer mortality significantly lower in the screening group

The RCT, known as the UK Age trial, was conducted in England, Wales, and Scotland and enrolled 160,921 women from 1990 through 1997.7 Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to observation or annual screening mammogram beginning at age 39–41 until age 48. (In the United Kingdom, all women are screened starting at age 50.) Study enrollees were followed for a median of 22.8 years, and the primary outcome was breast cancer mortality.

The study results showed a 25% relative risk (RR) reduction in breast cancer mortality at 10 years of follow-up in the mammography group compared with the unscreened women (83 breast cancer deaths in the mammography group vs 219 in the observation group [RR, 0.75; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.58–0.97; P = .029]). Based on the prevalence of breast cancer in women in their 40s, this 25% relative risk reduction translates into approximately 1 less death per 1,000 women who undergo routine screening in their 40s.

While there was no additional significant mortality reduction beyond 10 years of follow-up, as noted mammography is offered routinely starting at age 50 to all women in the United Kingdom. The authors concluded that “reducing the lower age limit for screening from 50 to 40 years [of age] could potentially reduce breast cancer mortality.”

Was overdiagnosis a concern? Another finding in this trial was related to overdiagnosis of breast cancer in the screened group. Overdiagnosis refers to mammographic-only diagnosis (that is, no clinical findings) of nonaggressive breast cancer, which would remain indolent and not harm the patient. The study results demonstrated essentially no overdiagnosis in women screened at age 40 compared with the unscreened group.

Continue to: Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths...

Large trial, long follow-up are key strengths

The UK Age trial’s primary strength is its study design: a large population-based RCT that included diverse participants with the critical study outcome for cancer screening (mortality). The study’s long-term follow-up is another key strength, since breast cancer mortality typically occurs 7 to 10 years after diagnosis. In addition, results were available for 99.9% of the women enrolled in the trial (that is, only 0.1% of women were lost to follow-up). Interestingly, the demonstrated mortality reduction with screening mammography for women in their 40s validates the mortality benefit demonstrated in other large RCTs of women in their 40s.1

Another strong point is that the study addresses the issue of whether screening women in their 40s results in overdiagnosis compared with women who start screening in their 50s. Further, this study validates a prior observational study that mammographic findings of nonprogressive cancers do not disappear, so nonaggressive cancers that present on mammography in women in their 40s still would be detected when women start screening in their 50s.8

Study limitations should be noted

The study has several limitations. For example, significant improvements have been made in breast cancer treatments that may mitigate against the positive impact of screening mammography. The impact of changed breast cancer management over the past 20 years could not be addressed with this study’s design since women would have been treated in the 1990s. In addition, substantial improvements have occurred in breast cancer screening standards (2 views vs the single view used in the study) and technology since the 1990s. Current mammography includes nearly uniform use of either digital mammography (DM) or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), both of which improve breast cancer detection for women in their 40s compared with the older film-screen technology. In addition, DBT reduces false-positive results by approximately 40%, resulting in fewer callbacks and biopsies. While improved cancer detection and reduced false-positive results are seen with DM and DBT, whether these technology improvements result in improved breast cancer mortality has not yet been sufficiently studied.

Perhaps the most important limitation in this study is that the women did not undergo routine risk assessment before trial entry to assure that they all were at “average risk.” As a result, both high- and average-risk women would have been included in this population-based trial. Without risk stratification, it remains uncertain whether the reduction in breast cancer mortality disproportionately exists within a high-risk subgroup (such as breast cancer gene mutation carriers).

Finally, the cost efficacy of routine screening mammography for women in their 40s was not evaluated in this study.

The UK Age trial in perspective

The good news is that there is the clear evidence that breast cancer mortality rates (deaths per 100,000) have decreased by about 40% over the past 50 years, likely due to improvements in breast cancer treatment and routine screening mammography.9 Breast cancer mortality reduction is particularly important because breast cancer remains the most common cancer and is the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States. In the past decade, considerable debate has arisen arguing whether this reduction in breast cancer mortality is due to improved treatments, routine screening mammography, or both. Authors of a retrospective trial in Australia, recently reviewed in OBG Management, suggested that the majority of improvement is due to improvements in treatment.3,10 However, as the authors pointed out, due to the trial’s retrospective design, causality only can be inferred. The current UK Age trial does add to the numerous prospective trials demonstrating mortality benefit for mammography in women in their 40s.11

What remains a challenge for clinicians, and for women struggling with the mammography question, is the absence of risk assessment in these long-term RCT trials as well as in the large retrospective database studies. Without risk stratification, these studies treated all the study population as “average risk.” Because breast cancer risk assessment is sporadically performed in clinical practice and there are no published RCTs of screening mammography in risk-assessed “average risk” women in their 40s, it remains uncertain whether the women benefiting from screening in their 40s are in a high-risk group or whether women of average risk in this age group also are benefiting from routine screening mammography.

Continue to: What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice...

What’s next: Incorporate routine risk assessment into clinical practice

It is not time to abandon screening mammography for all women in their 40s. Rather, routine risk assessment should be performed using one of many available validated or widely tested tools, a recommendation supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the US Preventive Services Task Force.5,6,12

Ideally, these tools can be incorporated into an electronic health record and prepopulated using already available patient data (such as age, reproductive risk factors, current medications, breast density if available, and family history). Prepopulating available data into breast cancer risk calculators would allow clinicians to spend time on counseling women regarding breast cancer risk and appropriate screening methods. The TABLE provides a summary of useful breast cancer risk calculators and includes comments about their utility and significant limitations and benefits. In addition to breast cancer risk, the more comprehensive risk calculators (Tyrer-Cuzick and BOADICEA) allow calculation of ovarian cancer risk and gene mutation risk.

Routinely performing breast cancer risk assessment can guide discussions of screening mammography and can provide data for conducting a more individualized discussion on cancer genetic counseling and testing, risk reduction methods in high-risk women, and possible use of intensive breast cancer screening tools in identified high-risk women.

Ultimately, debating the question of whether all women should have routine breast cancer screening in their 40s should be passé. Ideally, all women should undergo breast cancer risk assessment in their 20s. Risk assessment results can then be used to guide the discussion of multiple potential interventions for women in their 40s (or earlier if appropriate), including routine screening mammography, cancer genetic counseling and testing in appropriate individuals, and intervention for women who are identified at high risk.

Absent breast cancer risk assessment, screening mammography still should be offered to women in their 40s, and the decision to proceed should be based on a discussion of risks, benefits, and the value the patient places on these factors.●

- Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, et al. Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:244-255.

- Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998-2005.

- Burton R, Stevenson C. Assessment of breast cancer mortality trends associated with mammographic screening and adjuvant therapy from 1986 to 2013 in the state of Victoria, Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208249-e.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Humphrey L, et al. A systematic review to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Evidence syntheses No. 124. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05201-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1362-1389.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1-e16.

- Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H, et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1165-1172.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, et al. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:863-867.

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438-451.

- Kaunitz AM. How effective is screening mammography for preventing breast cancer mortality? OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):17,49.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314:1599-1614.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

- Nelson HD, Fu R, Cantor A, et al. Effectiveness of breast cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:244-255.

- Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1998-2005.

- Burton R, Stevenson C. Assessment of breast cancer mortality trends associated with mammographic screening and adjuvant therapy from 1986 to 2013 in the state of Victoria, Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208249-e.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Humphrey L, et al. A systematic review to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Evidence syntheses No. 124. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05201-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1362-1389.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average-risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e1-e16.

- Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H, et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1165-1172.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, et al. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:863-867.

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438-451.

- Kaunitz AM. How effective is screening mammography for preventing breast cancer mortality? OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):17,49.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314:1599-1614.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.