User login

Psychogastroenterology, or gastrointestinal psychology, refers to psychosocial research and clinical practice related to GI conditions. This field is situated within a biopsychosocial model of illness and grounded in an understanding of the gut-brain axis. A key feature of GI psychology intervention is behavioral symptom management. Commonly referred to as “brain-gut psychotherapies,” the primary goal of these interventions is to reduce GI symptoms and their impact on those experiencing them. Additionally, GI-focused psychotherapies can help patients with GI disorders cope with their symptoms, diagnosis, or treatment.

GI psychology providers

GI-focused psychotherapies are typically provided by clinical health psychologists (PhDs or PsyDs) with specialized training in GI disorders, although sometimes they are provided by a clinical social worker or advanced-practice nursing provider. Psychologists that identify GI as their primary specialty area often refer to themselves as “GI psychologists.” Psychologists that treat patients with a variety of medical concerns, which may include GI disorders, typically refer to themselves with the broader term, “health psychologists.”

Interventions

A variety of psychological treatments have been applied to GI populations, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), gut-directed hypnotherapy (GDH), psychodynamic interpersonal therapy, relaxation training, and mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychological therapies have been shown to be useful in a variety of GI disorders, with a number needed to treat of four in IBS.1 Common ingredients of GI-focused psychotherapy interventions include psychoeducation regarding the gut-brain relationship and relaxation strategies to provide in-the-moment tools to deescalate the body’s stress response.

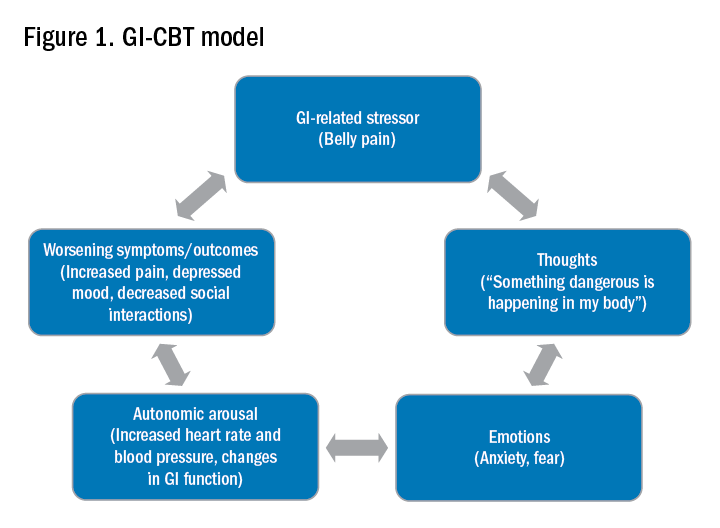

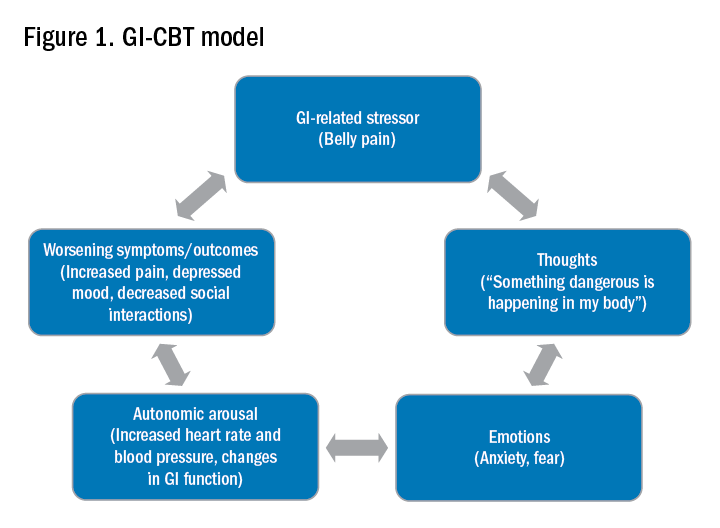

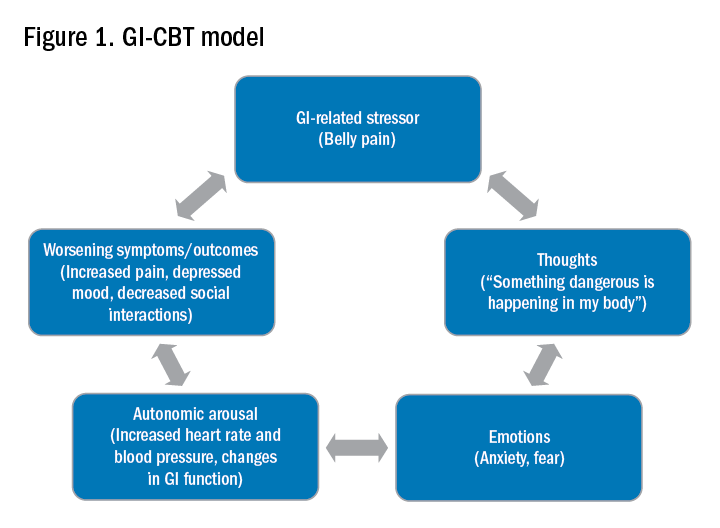

CBT and GDH are the most commonly used interventions across a range of GI conditions, with the bulk of empirical evidence in IBS.2-5 CBT is a theoretical orientation in which thoughts and behaviors are understood to be modifiable factors that impact emotions and physical sensations. When utilized in a GI setting (i.e., GI-CBT), treatment aims to address GI-specific outcomes such as reducing GI symptoms, optimizing health care utilization, and improving quality of life. These interventions target cognitive and behavioral factors common among GI patient populations, such as GI-specific anxiety, symptom hypervigilance, and rigid coping strategies. See Figure 1 for a GI-CBT model.

While research studies often implement manualized protocols, in clinical practice many GI psychologists use cognitive-behavioral interventions flexibly to tailor them to each patient’s presentation, while also integrating theory and practice from other types of therapies such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; pronounced as one word). ACT, a “new wave” therapy derived from traditional CBT, emphasizes acceptance of distress (including GI symptoms), with a focus on engaging in values-based activities rather than symptom reduction.

Clinical hypnotherapy is utilized in a variety of medical specialties and has been studied in GI disorders for over 30 years. There are two evidence-based gut-directed hypnotherapy protocols, the Manchester6 and the North Carolina,7 that are widely used by GI psychologists. Though the exact mechanisms of hypnotherapy are unknown, it is thought to improve GI symptoms by modulating autonomic arousal and nerve sensitivity in the GI tract.

Evaluation

GI psychologists typically meet with patients for a 1-hour evaluation to determine appropriateness for psychogastroenterology intervention and develop a treatment plan. If GI-focused psychotherapy is indicated, patients are typically offered a course of treatment ranging from four to eight sessions. Depending on the nature of the patient’s concerns, longer courses of treatment may be offered, such as for with patients with active inflammatory bowel disease undergoing changes in medical treatment.

Appropriateness for psychogastroenterology treatment

Ideal patients are those who are psychologically stable and whose distress is primarily related to GI concerns, as opposed to family, work, or other situational stressors. While these other stressors can certainly impact GI symptoms, general mental health professionals are best suited to assist patients with these concerns. Patients experiencing more severe mental health concerns may be recommended to pursue a different treatment, such as mental health treatment for depression or anxiety or specialized treatments for trauma, eating disorders, or substance use. In both cases, once these general, non-GI, stressors or significant mental health concerns are more optimally managed, patients are likely to benefit from a GI-focused psychological treatment. Note, however, that because a GI psychologist’s particular practice can vary because of interest, experience, and institutional factors, it is best to connect directly with the GI psychologist you work with to clarify the types of referrals they are comfortable seeing and any specific characteristics of their practice.

Best practice recommendations for gastroenterologists

Developing a collaborative relationship with the GI psychologist, as well as any therapists to whom you regularly refer patients, is key to the success of integrated care. When talking to patients about the referral, refer to the GI psychologist as your colleague and a member of the treatment team. Maintain communication with the GI psychologist, and let the patient know that you are doing so.

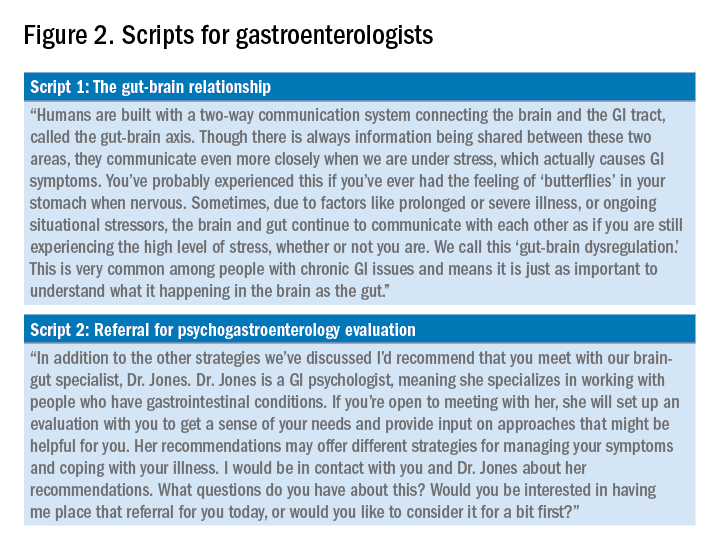

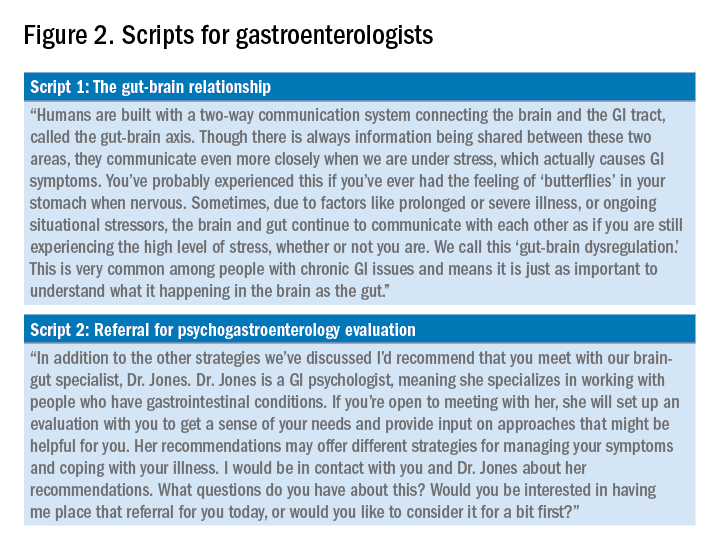

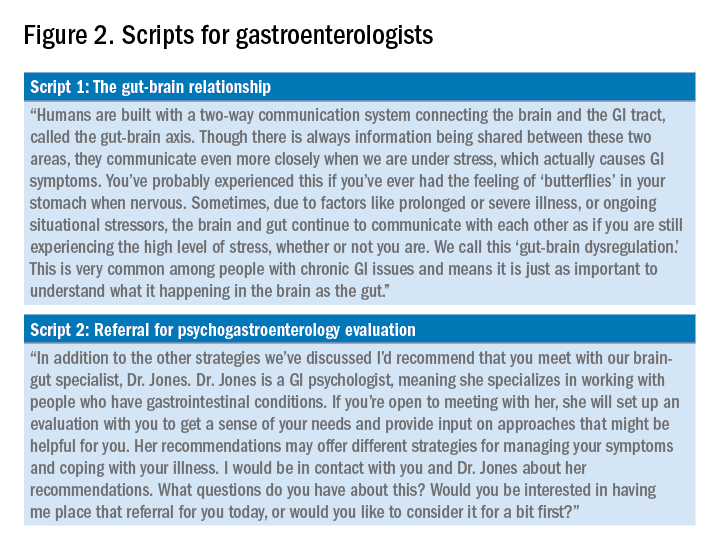

When referring a patient, do so after you have completed your work-up and have optimized basic medical management for their condition but suspect that psychosocial factors may be negatively impacting their symptoms or ability to cope. Present the referral as an evaluation rather than implying a guarantee of treatment. This is particularly helpful in those cases where the patient is recommended to pursue a different treatment prior to GI-focused psychotherapy. Additionally, avoid telling patients that they are being referred for a specific intervention such as “a referral for CBT” or “a referral for hypnotherapy,” as the GI psychologist will recommend the most appropriate treatment for the patient upon evaluation. See Figure 2 for example scripts to use when referring.

Expect to maintain communication with the GI psychologist after making the referral. GI psychologists typically send the referring provider a written summary following the initial evaluation and conclusion of treatment and, in some cases, provide updates throughout. Be prepared to answer questions or provide input as requested. Not only may the psychologist have questions about the medical diagnosis or treatment, but they may enlist your help for medical expert opinion during treatment to address misinformation, which can often fuel concerns like treatment nonadherence or anxiety.

Identifying a psychogastroenterology provider

In recent years there has been significant growth in the training and hiring of GI psychologists, and it is increasingly common for GI psychologists to be employed at academic medical centers. However, the majority of gastroenterologists do not have access to a fully integrated or co-located GI psychologist. In these cases, gastroenterologists should search for other health psychology options in their area, such as psychologists or clinical social workers with experience with patients with chronic medical conditions and CBT. One positive product of the COVID-19 pandemic is that telemedicine has become increasingly utilized, and in some cases GI psychologists are able to provide virtual therapy to patients across state lines. However, this should be confirmed with the therapy practice as there are numerous factors to consider regarding virtual practice.

Dr. Bedell is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Resources available

To locate a GI psychology provider in your area: Search the Rome Psychogastroenterology directory (https://romegipsych.org/).

To locate general mental health providers: Search the Psychology Today website using the therapist finder function, which allows patients or providers to search by insurance, location, and specialty area (www.psychologytoday.com/us). The patient can also request a list of in-network psychotherapy providers from their insurance company and may find it helpful to cross-check these providers for potential fit by searching them online.

References

1. Ford AC et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jan;114(1):21-39. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5.

2. Laird KT et al. Short-term and long-term efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jul;14(7):937-47.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.020.

3. Lackner JM et al. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul;155(1):47-57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.063.

4. Lövdahl J et al. Nurse-administered, gut-directed hypnotherapy in IBS: Efficacy and factors predicting a positive response. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015 Jul;58(1):100-14. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2015.1030492.

5. Smith GD. Effect of nurse-led gut-directed hypnotherapy upon health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Nurs. 2006 Jun;15(6):678-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01356.x.

6. Gonsalkorale WM. Gut-directed hypnotherapy: the Manchester approach for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):27-50. doi: 10.1080/00207140500323030.

7. Palsson OS. Standardized hypnosis treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: The North Carolina protocol. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):51-64. doi: 10.1080/00207140500322933.

Psychogastroenterology, or gastrointestinal psychology, refers to psychosocial research and clinical practice related to GI conditions. This field is situated within a biopsychosocial model of illness and grounded in an understanding of the gut-brain axis. A key feature of GI psychology intervention is behavioral symptom management. Commonly referred to as “brain-gut psychotherapies,” the primary goal of these interventions is to reduce GI symptoms and their impact on those experiencing them. Additionally, GI-focused psychotherapies can help patients with GI disorders cope with their symptoms, diagnosis, or treatment.

GI psychology providers

GI-focused psychotherapies are typically provided by clinical health psychologists (PhDs or PsyDs) with specialized training in GI disorders, although sometimes they are provided by a clinical social worker or advanced-practice nursing provider. Psychologists that identify GI as their primary specialty area often refer to themselves as “GI psychologists.” Psychologists that treat patients with a variety of medical concerns, which may include GI disorders, typically refer to themselves with the broader term, “health psychologists.”

Interventions

A variety of psychological treatments have been applied to GI populations, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), gut-directed hypnotherapy (GDH), psychodynamic interpersonal therapy, relaxation training, and mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychological therapies have been shown to be useful in a variety of GI disorders, with a number needed to treat of four in IBS.1 Common ingredients of GI-focused psychotherapy interventions include psychoeducation regarding the gut-brain relationship and relaxation strategies to provide in-the-moment tools to deescalate the body’s stress response.

CBT and GDH are the most commonly used interventions across a range of GI conditions, with the bulk of empirical evidence in IBS.2-5 CBT is a theoretical orientation in which thoughts and behaviors are understood to be modifiable factors that impact emotions and physical sensations. When utilized in a GI setting (i.e., GI-CBT), treatment aims to address GI-specific outcomes such as reducing GI symptoms, optimizing health care utilization, and improving quality of life. These interventions target cognitive and behavioral factors common among GI patient populations, such as GI-specific anxiety, symptom hypervigilance, and rigid coping strategies. See Figure 1 for a GI-CBT model.

While research studies often implement manualized protocols, in clinical practice many GI psychologists use cognitive-behavioral interventions flexibly to tailor them to each patient’s presentation, while also integrating theory and practice from other types of therapies such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; pronounced as one word). ACT, a “new wave” therapy derived from traditional CBT, emphasizes acceptance of distress (including GI symptoms), with a focus on engaging in values-based activities rather than symptom reduction.

Clinical hypnotherapy is utilized in a variety of medical specialties and has been studied in GI disorders for over 30 years. There are two evidence-based gut-directed hypnotherapy protocols, the Manchester6 and the North Carolina,7 that are widely used by GI psychologists. Though the exact mechanisms of hypnotherapy are unknown, it is thought to improve GI symptoms by modulating autonomic arousal and nerve sensitivity in the GI tract.

Evaluation

GI psychologists typically meet with patients for a 1-hour evaluation to determine appropriateness for psychogastroenterology intervention and develop a treatment plan. If GI-focused psychotherapy is indicated, patients are typically offered a course of treatment ranging from four to eight sessions. Depending on the nature of the patient’s concerns, longer courses of treatment may be offered, such as for with patients with active inflammatory bowel disease undergoing changes in medical treatment.

Appropriateness for psychogastroenterology treatment

Ideal patients are those who are psychologically stable and whose distress is primarily related to GI concerns, as opposed to family, work, or other situational stressors. While these other stressors can certainly impact GI symptoms, general mental health professionals are best suited to assist patients with these concerns. Patients experiencing more severe mental health concerns may be recommended to pursue a different treatment, such as mental health treatment for depression or anxiety or specialized treatments for trauma, eating disorders, or substance use. In both cases, once these general, non-GI, stressors or significant mental health concerns are more optimally managed, patients are likely to benefit from a GI-focused psychological treatment. Note, however, that because a GI psychologist’s particular practice can vary because of interest, experience, and institutional factors, it is best to connect directly with the GI psychologist you work with to clarify the types of referrals they are comfortable seeing and any specific characteristics of their practice.

Best practice recommendations for gastroenterologists

Developing a collaborative relationship with the GI psychologist, as well as any therapists to whom you regularly refer patients, is key to the success of integrated care. When talking to patients about the referral, refer to the GI psychologist as your colleague and a member of the treatment team. Maintain communication with the GI psychologist, and let the patient know that you are doing so.

When referring a patient, do so after you have completed your work-up and have optimized basic medical management for their condition but suspect that psychosocial factors may be negatively impacting their symptoms or ability to cope. Present the referral as an evaluation rather than implying a guarantee of treatment. This is particularly helpful in those cases where the patient is recommended to pursue a different treatment prior to GI-focused psychotherapy. Additionally, avoid telling patients that they are being referred for a specific intervention such as “a referral for CBT” or “a referral for hypnotherapy,” as the GI psychologist will recommend the most appropriate treatment for the patient upon evaluation. See Figure 2 for example scripts to use when referring.

Expect to maintain communication with the GI psychologist after making the referral. GI psychologists typically send the referring provider a written summary following the initial evaluation and conclusion of treatment and, in some cases, provide updates throughout. Be prepared to answer questions or provide input as requested. Not only may the psychologist have questions about the medical diagnosis or treatment, but they may enlist your help for medical expert opinion during treatment to address misinformation, which can often fuel concerns like treatment nonadherence or anxiety.

Identifying a psychogastroenterology provider

In recent years there has been significant growth in the training and hiring of GI psychologists, and it is increasingly common for GI psychologists to be employed at academic medical centers. However, the majority of gastroenterologists do not have access to a fully integrated or co-located GI psychologist. In these cases, gastroenterologists should search for other health psychology options in their area, such as psychologists or clinical social workers with experience with patients with chronic medical conditions and CBT. One positive product of the COVID-19 pandemic is that telemedicine has become increasingly utilized, and in some cases GI psychologists are able to provide virtual therapy to patients across state lines. However, this should be confirmed with the therapy practice as there are numerous factors to consider regarding virtual practice.

Dr. Bedell is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Resources available

To locate a GI psychology provider in your area: Search the Rome Psychogastroenterology directory (https://romegipsych.org/).

To locate general mental health providers: Search the Psychology Today website using the therapist finder function, which allows patients or providers to search by insurance, location, and specialty area (www.psychologytoday.com/us). The patient can also request a list of in-network psychotherapy providers from their insurance company and may find it helpful to cross-check these providers for potential fit by searching them online.

References

1. Ford AC et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jan;114(1):21-39. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5.

2. Laird KT et al. Short-term and long-term efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jul;14(7):937-47.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.020.

3. Lackner JM et al. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul;155(1):47-57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.063.

4. Lövdahl J et al. Nurse-administered, gut-directed hypnotherapy in IBS: Efficacy and factors predicting a positive response. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015 Jul;58(1):100-14. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2015.1030492.

5. Smith GD. Effect of nurse-led gut-directed hypnotherapy upon health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Nurs. 2006 Jun;15(6):678-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01356.x.

6. Gonsalkorale WM. Gut-directed hypnotherapy: the Manchester approach for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):27-50. doi: 10.1080/00207140500323030.

7. Palsson OS. Standardized hypnosis treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: The North Carolina protocol. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):51-64. doi: 10.1080/00207140500322933.

Psychogastroenterology, or gastrointestinal psychology, refers to psychosocial research and clinical practice related to GI conditions. This field is situated within a biopsychosocial model of illness and grounded in an understanding of the gut-brain axis. A key feature of GI psychology intervention is behavioral symptom management. Commonly referred to as “brain-gut psychotherapies,” the primary goal of these interventions is to reduce GI symptoms and their impact on those experiencing them. Additionally, GI-focused psychotherapies can help patients with GI disorders cope with their symptoms, diagnosis, or treatment.

GI psychology providers

GI-focused psychotherapies are typically provided by clinical health psychologists (PhDs or PsyDs) with specialized training in GI disorders, although sometimes they are provided by a clinical social worker or advanced-practice nursing provider. Psychologists that identify GI as their primary specialty area often refer to themselves as “GI psychologists.” Psychologists that treat patients with a variety of medical concerns, which may include GI disorders, typically refer to themselves with the broader term, “health psychologists.”

Interventions

A variety of psychological treatments have been applied to GI populations, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), gut-directed hypnotherapy (GDH), psychodynamic interpersonal therapy, relaxation training, and mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychological therapies have been shown to be useful in a variety of GI disorders, with a number needed to treat of four in IBS.1 Common ingredients of GI-focused psychotherapy interventions include psychoeducation regarding the gut-brain relationship and relaxation strategies to provide in-the-moment tools to deescalate the body’s stress response.

CBT and GDH are the most commonly used interventions across a range of GI conditions, with the bulk of empirical evidence in IBS.2-5 CBT is a theoretical orientation in which thoughts and behaviors are understood to be modifiable factors that impact emotions and physical sensations. When utilized in a GI setting (i.e., GI-CBT), treatment aims to address GI-specific outcomes such as reducing GI symptoms, optimizing health care utilization, and improving quality of life. These interventions target cognitive and behavioral factors common among GI patient populations, such as GI-specific anxiety, symptom hypervigilance, and rigid coping strategies. See Figure 1 for a GI-CBT model.

While research studies often implement manualized protocols, in clinical practice many GI psychologists use cognitive-behavioral interventions flexibly to tailor them to each patient’s presentation, while also integrating theory and practice from other types of therapies such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; pronounced as one word). ACT, a “new wave” therapy derived from traditional CBT, emphasizes acceptance of distress (including GI symptoms), with a focus on engaging in values-based activities rather than symptom reduction.

Clinical hypnotherapy is utilized in a variety of medical specialties and has been studied in GI disorders for over 30 years. There are two evidence-based gut-directed hypnotherapy protocols, the Manchester6 and the North Carolina,7 that are widely used by GI psychologists. Though the exact mechanisms of hypnotherapy are unknown, it is thought to improve GI symptoms by modulating autonomic arousal and nerve sensitivity in the GI tract.

Evaluation

GI psychologists typically meet with patients for a 1-hour evaluation to determine appropriateness for psychogastroenterology intervention and develop a treatment plan. If GI-focused psychotherapy is indicated, patients are typically offered a course of treatment ranging from four to eight sessions. Depending on the nature of the patient’s concerns, longer courses of treatment may be offered, such as for with patients with active inflammatory bowel disease undergoing changes in medical treatment.

Appropriateness for psychogastroenterology treatment

Ideal patients are those who are psychologically stable and whose distress is primarily related to GI concerns, as opposed to family, work, or other situational stressors. While these other stressors can certainly impact GI symptoms, general mental health professionals are best suited to assist patients with these concerns. Patients experiencing more severe mental health concerns may be recommended to pursue a different treatment, such as mental health treatment for depression or anxiety or specialized treatments for trauma, eating disorders, or substance use. In both cases, once these general, non-GI, stressors or significant mental health concerns are more optimally managed, patients are likely to benefit from a GI-focused psychological treatment. Note, however, that because a GI psychologist’s particular practice can vary because of interest, experience, and institutional factors, it is best to connect directly with the GI psychologist you work with to clarify the types of referrals they are comfortable seeing and any specific characteristics of their practice.

Best practice recommendations for gastroenterologists

Developing a collaborative relationship with the GI psychologist, as well as any therapists to whom you regularly refer patients, is key to the success of integrated care. When talking to patients about the referral, refer to the GI psychologist as your colleague and a member of the treatment team. Maintain communication with the GI psychologist, and let the patient know that you are doing so.

When referring a patient, do so after you have completed your work-up and have optimized basic medical management for their condition but suspect that psychosocial factors may be negatively impacting their symptoms or ability to cope. Present the referral as an evaluation rather than implying a guarantee of treatment. This is particularly helpful in those cases where the patient is recommended to pursue a different treatment prior to GI-focused psychotherapy. Additionally, avoid telling patients that they are being referred for a specific intervention such as “a referral for CBT” or “a referral for hypnotherapy,” as the GI psychologist will recommend the most appropriate treatment for the patient upon evaluation. See Figure 2 for example scripts to use when referring.

Expect to maintain communication with the GI psychologist after making the referral. GI psychologists typically send the referring provider a written summary following the initial evaluation and conclusion of treatment and, in some cases, provide updates throughout. Be prepared to answer questions or provide input as requested. Not only may the psychologist have questions about the medical diagnosis or treatment, but they may enlist your help for medical expert opinion during treatment to address misinformation, which can often fuel concerns like treatment nonadherence or anxiety.

Identifying a psychogastroenterology provider

In recent years there has been significant growth in the training and hiring of GI psychologists, and it is increasingly common for GI psychologists to be employed at academic medical centers. However, the majority of gastroenterologists do not have access to a fully integrated or co-located GI psychologist. In these cases, gastroenterologists should search for other health psychology options in their area, such as psychologists or clinical social workers with experience with patients with chronic medical conditions and CBT. One positive product of the COVID-19 pandemic is that telemedicine has become increasingly utilized, and in some cases GI psychologists are able to provide virtual therapy to patients across state lines. However, this should be confirmed with the therapy practice as there are numerous factors to consider regarding virtual practice.

Dr. Bedell is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Resources available

To locate a GI psychology provider in your area: Search the Rome Psychogastroenterology directory (https://romegipsych.org/).

To locate general mental health providers: Search the Psychology Today website using the therapist finder function, which allows patients or providers to search by insurance, location, and specialty area (www.psychologytoday.com/us). The patient can also request a list of in-network psychotherapy providers from their insurance company and may find it helpful to cross-check these providers for potential fit by searching them online.

References

1. Ford AC et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jan;114(1):21-39. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5.

2. Laird KT et al. Short-term and long-term efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jul;14(7):937-47.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.020.

3. Lackner JM et al. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul;155(1):47-57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.063.

4. Lövdahl J et al. Nurse-administered, gut-directed hypnotherapy in IBS: Efficacy and factors predicting a positive response. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015 Jul;58(1):100-14. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2015.1030492.

5. Smith GD. Effect of nurse-led gut-directed hypnotherapy upon health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Nurs. 2006 Jun;15(6):678-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01356.x.

6. Gonsalkorale WM. Gut-directed hypnotherapy: the Manchester approach for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):27-50. doi: 10.1080/00207140500323030.

7. Palsson OS. Standardized hypnosis treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: The North Carolina protocol. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2006 Jan;54(1):51-64. doi: 10.1080/00207140500322933.