User login

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

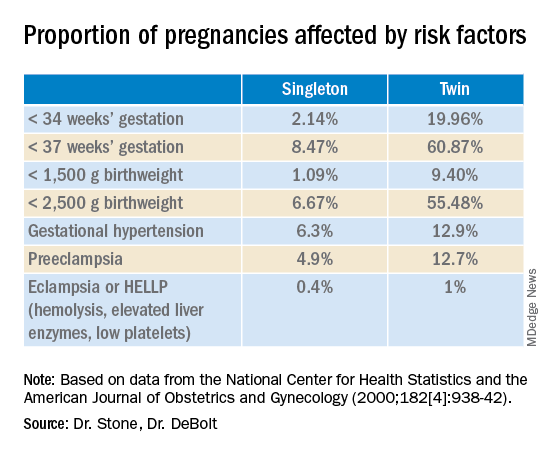

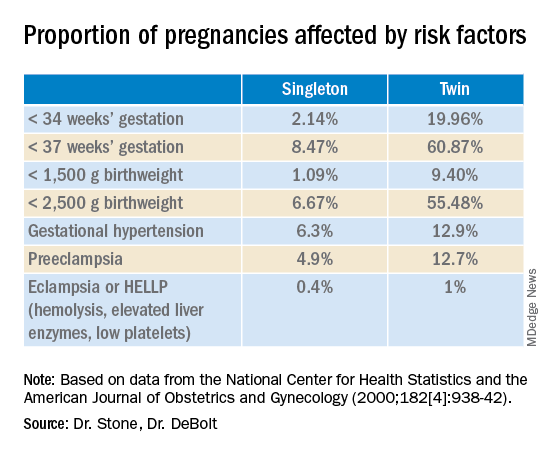

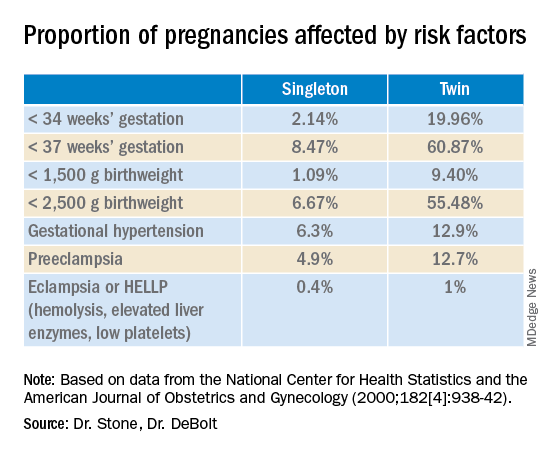

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

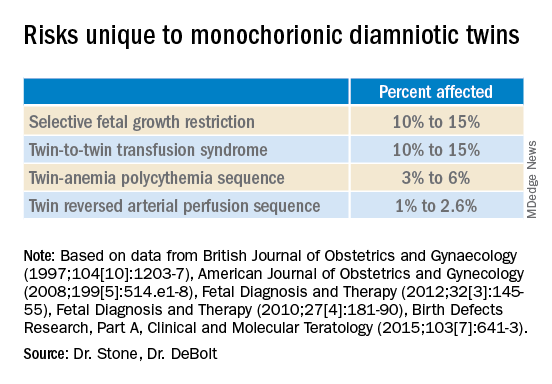

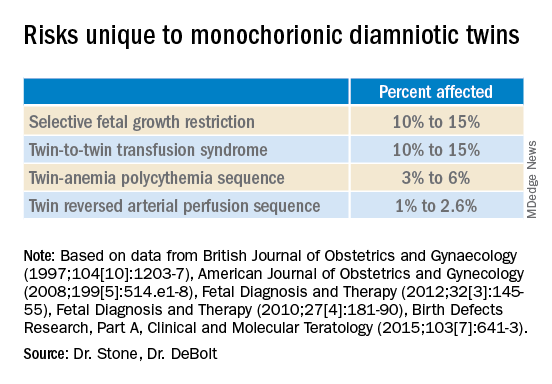

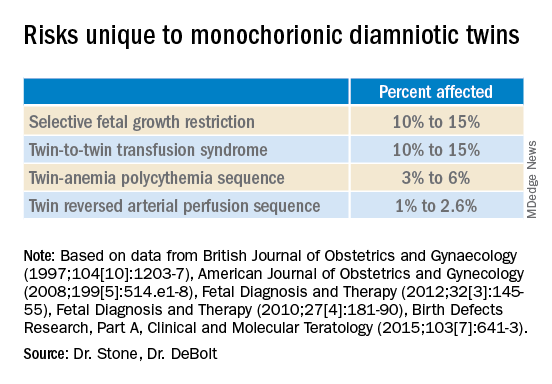

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

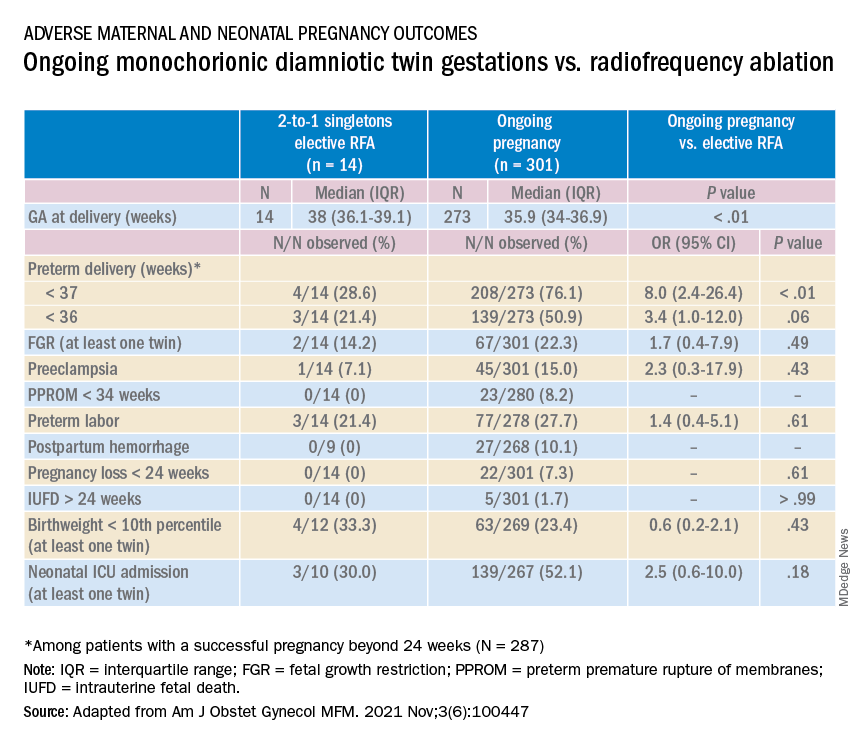

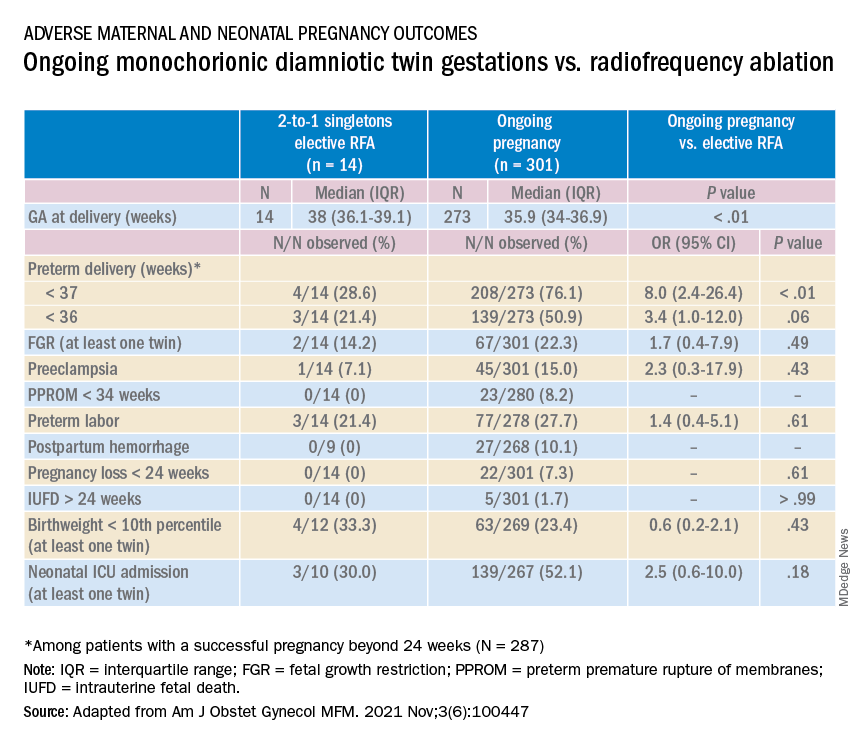

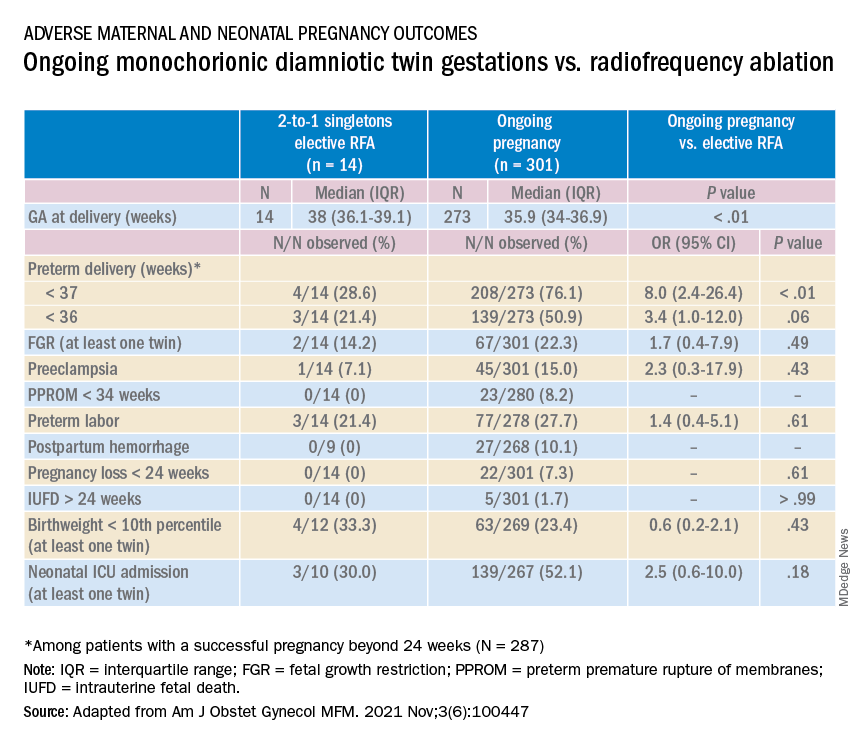

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.