User login

Although clinicians and patients generally are cautious when prescribing or using antipsychotics during pregnancy, inadequately controlled psychiatric illness poses risks to both mother and child. Calculating the risks and benefits of antipsychotic use during pregnancy is limited by an incomplete understanding of the true effectiveness and full spectrum of risks of these medications. Ethical principles prohibit the type of rigorous research that would be needed to achieve clarity on this issue. This article reviews studies that might help guide clinicians who are considering prescribing an atypical antipsychotic to manage psychiatric illness in a pregnant woman.

Antipsychotic efficacy in pregnancy

All atypical antipsychotics available in the United States are FDA-approved for treating schizophrenia; some also have been approved for treating bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, or symptoms associated with autism (Table 1). Atypical antipsychotics frequently are used off-label for these and other categories of psychiatric illness, including unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

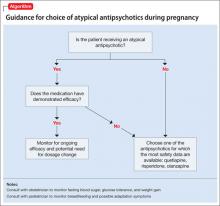

Studies of pharmacotherapy in pregnant women tend to focus more on safety rather than efficacy. Clinical decisions for an individual patient are best made based on knowledge about which medications have been effective for that patient in the past (Algorithm).

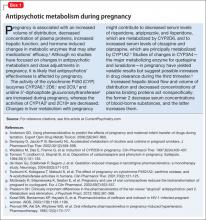

However, safety concerns in pregnancy may require modifying an existing regimen. In other cases, new symptoms arise during pregnancy and necessitate new medications. Additionally, a drug’s effectiveness may be affected by physiologic changes of pregnancy that can alter drug metabolism,1 potentially necessitating dose changes (Box 1).

Risks of treatment vs illness

Complete safety data on the use of any psychotropic medication during pregnancy are not available. To date, studies of atypical antipsychotics do not support any increased risk for congenital malformations large enough to be detected in medium-sized samples,2-4 although it is possible that there are increases in risk that are below the detection limit of these studies. Data regarding delivery outcomes are conflicting and difficult to interpret.

Several studies2-4 have yielded inconsistent results, including:

• risks for increased birth weight and large for gestational age3

• risks for low birth weight and small for gestational age2

• no significant differences from controls.4

Atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of gestational diabetes, whereas typical antipsychotics do not appear to increase this risk.4

Until recently, research has been limited by difficulties in separating the effects of treatment from the effects of psychiatric illness, which include intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, preterm birth, low Apgar scores, and congenital defects.5 In addition, most studies address early and easily measurable outcomes such as preterm labor, birth weight, and congenital malformations. Researchers are just beginning to investigate more subtle and long-term potential behavioral effects.

Several recent studies have explored outcomes associated with antipsychotic use during pregnancy while attempting to separate the effects of treatment from those of disease (Box 2).

Data on atypicals

Aripiprazole. Case reports of aripiprazole use during pregnancy have reported difficulties including transient unexplained fetal tachycardia that required emergent caesarean section6 and transient respiratory distress.7 Several small case series were not powered to detect risks related to aripiprazole.8,9

Animal data suggest teratogenic potential at dosages 3 and 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.10,11 Two studies7,12 that measured placental transfer of aripiprazole found cord-to-maternal serum concentration ratios ranging from 0.47 to 0.63, which is similar to the ratios for quetiapine and risperidone and lower than those for olanzapine and haloperidol.13

There are insufficient data to identify risks related to aripiprazole compared with other drugs in its class, and fewer reports are available than for other atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine and olanzapine. Placental transfer appears to be on the lower end of the spectrum for drugs in this class. Aripiprazole would be an acceptable choice for a woman who had a history of response to aripiprazole but likely would not be a first choice for a woman requiring a new medication during pregnancy.

Clozapine. In case reports, adverse effects associated with clozapine exposure during pregnancy include major malformations, gestational metabolic complications, poor pregnancy outcome, and perinatal adverse reactions. In one case, neonatal plasma clozapine concentrations were found to be twice that found in maternal plasma.14 Animal data have shown no evidence of increased teratogenicity at 2 to 4 times the maximum recommended human dosages.15 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with clozapine (11 exposures). Four other series2-4,16 were underpowered to detect concerns related specifically to clozapine.

There are insufficient data to identify risks related specifically to clozapine use during pregnancy. However, the rare but severe adverse effects associated with clozapine in other patient populations—including agranulocytosis and severe constipation17—could be devastating in a pregnant patient, which suggests this medication would not be a first-line treatment.

Olanzapine. In postmarketing surveillance studies and case reports, there have been have anecdotal cases of fetal malformations related to olanzapine use during pregnancy. Several larger studies2-4,8,16 did not find higher rates of congenital malformations or any pattern of malformation types, although none were designed or powered to examine rare events. Animal data show no evidence of teratogenicity.18 A study comparing rates of placental passage of antipsychotics13 found higher rates for olanzapine than for quetiapine and risperidone, as well as higher prevalence of low birth weight and perinatal complications. A neonatal withdrawal syndrome has also been reported.19 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with olanzapine.

Data suggest that olanzapine may be associated with somewhat higher rates of the adverse effects attributable to atypical antipsychotics (gestational diabetes and possibly macrocephaly), which could be related to olanzapine’s relatively higher rate of placental passage. Olanzapine could be a reasonable choice in a woman who had a history of good response to this medication, but would be lower priority than quetiapine when a new drug is indicated during pregnancy.

Quetiapine. In clinical trials, quetiapine had lower rates of placental passage compared with risperidone and olanzapine.13 One case report found only small changes in quetiapine serum levels during pregnancy.20 Prospective studies (90 exposures,8 36 exposures,2 7 exposures,16 4 exposures,3 and 4 exposures4) show no increase in fetal malformations or adverse neonatal health outcomes related to quetiapine, and manufacturer safety data reveal no teratogenic effect, although delays in fetal skeletal ossification were seen in rats and rabbits at doses comparable to the recommended human range.21

Quetiapine is a reasonable first choice when a new atypical antipsychotic is indicated for a pregnant patient.

Risperidone. Rates of placental passage of risperidone are higher compared with quetiapine.13 Postmarketing surveillance data (265 exposures22 and 10 exposures23) and prospective studies (including 72 exposures,8 49 exposures,2 51 exposures,4 16 exposures,16 and 5 exposures3) suggest risperidone has no major teratogenic effect. When malformations were present, they were similar to expected rates and types of malformations, and no specific malformation type was overrepresented. However, in some cases, researchers noted a withdrawal-emergent syndrome that included various combinations of tremors, irritability, poor feeding, and somnolence.22 Animal data are similarly reassuring, although increases in early fetal mortality and (potentially related) changes in maternal behavior have been observed in rats.24,25 A major caveat with risperidone is its propensity to cause hyperprolactinemia, which is detrimental to efforts to conceive and maintain a pregnancy.26,27

Risperidone is not associated with higher rates of adverse events in pregnancy than other atypical antipsychotics. It would not be a first choice for a woman trying to conceive or in the early stages of pregnancy, but would be a reasonable choice for a woman already well into pregnancy.

Ziprasidone. Available reports are few and generally do not report findings on ziprasidone separately.8,28 Manufacturer data includes 5 spontaneous abortions, one malformation, and one stillbirth among 57 exposures,4 and available animal data suggest significant developmental toxicity and impaired fertility.29 In pregnant rats, ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.5 times the maximum human recommended dose resulted in delayed fetal skeletal ossification, increased stillbirths, and decreased fetal weight and postnatal survival, and ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.2 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in developmental delays and neurobehavioral impairments in offspring. In pregnant rabbits, ziprasidone dosed at 3 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in cardiac and renal malformations.29

Although available data are too sparse to draw reliable conclusions, the small amount of human data plus animal data suggest that ziprasidone should be less preferred than other atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Lurasidone. No data addressing lurasidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Material submitted to the FDA includes no evidence of teratogenicity or embryo-fetal toxicity in rat and rabbit studies using 3 and 12 times the maximum recommended human dose (80 mg) based on a body surface area comparison.30

Asenapine. No data specifically addressing asenapine use in humans during pregnancy are available. Studies in rats and rabbits found no increase in teratogenicity, but did find increases in postimplantation loss and decreases in pup survival and weight gain with maternal doses equivalent to less than the maximum recommended human dose.31

Iloperidone. No data specifically addressing iloperidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Animal studies of iloperidone found multiple developmental toxicities when iloperidone was administered during gestation.32 In one study, pregnant rats were given up to 26 times the maximum recommended human dose of 24 mg/d during the period of organogenesis. The highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths, decreased fetal weight and length, decreased fetal skeletal ossification, and increased minor fetal skeletal anomalies and variations. In a similar study using pregnant rabbits, the highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths and decreased fetal viability at term.

Paliperidone. In animal studies, there were no increases in fetal abnormalities when pregnant rats and rabbits were treated with up to 8 times the maximum recommended human dose of paliperidone during the period of organogenesis.33

A single case report34 measured levels of risperidone and its 9-hydroxy metabolite, paliperidone, in the breast milk of a mother who had taken risperidone during pregnancy and in the serum of her child. 9-OH-risperidone dose in breast milk was calculated as 4.7% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose, and serum levels in the infant were undetectable. No ill effects on the child were observed.

It is not possible to draw solid conclusions about atypical antipsychotics’ potential effects on human development from animal studies. Because of the lack of human data for the newer atypical antipsychotics—asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, paliperidone—in general these agents would not be advisable as first-line medications for treating pregnant women.

A few caveats

All atypical antipsychotics share the propensity to trigger or worsen glucose intolerance, which can have significant negative consequences in a pregnant patient. When deciding to use an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy, blood glucose should be monitored carefully and regularly.

Because all atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) are FDA pregnancy class C—indicating that animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks—the decision to use these medications must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits. Patients and their providers together should make a fully informed decision.

There is an urgent need for larger and better-designed investigations that will be sufficiently powered to detect differences in outcomes—particularly major malformations, preterm delivery, adverse events in labor and delivery, metabolic and anthropometric effects on the newborn, and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric outcomes for individuals exposed in utero—between women without mental illness, untreated women with mental illness, and women receiving atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy. Further research into the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of antipsychotics in pregnant women also would be useful. Clinicians can assist with these efforts by submitting their patient data to a pregnancy registry maintained by the Massachusetts General Hospital (see Related Resources).

Bottom Line

Treatment with atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy may increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes, but inadequately controlled mental illness also carries some degree of risk. The decision to use any atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits and made by the pregnant patient and her provider.

Related Resources

- Gentile S. Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):518-544. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879689.

- Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. www.womensmentalhealth.org/clinical-and-research-programs/pregnancyregistry.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Asenapine • Saphris Paliperidone • Invega

Clozapine • Clozaril Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Iloperidone • Fanapt Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lurasidone • Latuda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Chang J, Streitman D. Physiologic adaptations to pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2012;30(3):781-789.

2. McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4): 444-449; quiz 546.

3. Newham JJ, Thomas SH, MacRitchie K, et al. Birth weight of infants after maternal exposure to typical and atypical antipsychotics: prospective comparison study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):333-337.

4. Reis M, Kallen B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):279-288.

5. Matevosyan NR. Pregnancy and postpartum specifics in women with schizophrenia: a meta-study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(2):141-147.

6. Mendhekar DN, Sunder KR, Andrade C. Aripiprazole use in a pregnant schizoaffective woman. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):299-300.

7. Watanabe N, Kasahara M, Sugibayashi R, et al. Perinatal use of aripiprazole: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):377-379.

8. Bodén R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, et al. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):715-721.

9. Maáková E, Hubicˇková L. Antidepressant drug exposure during pregnancy. CZTIS small prospective study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2011;32(suppl 1):53-56.

10. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Ed.). Aripiprazole: Drugdex drug evaluations, 1974-2003. Princeton, NJ: Thomson Micromedex; 2003.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: Aripiprazole. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/21436slr006_abilify_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

12. Nguyen T, Teoh S, Hackett LP, et al. Placental transfer of aripiprazole. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):500-501.

13. Newport DJ, Calamaras MR, DeVane CL, et al. Atypical antipsychotic administration during late pregnancy: placental passage and obstetrical outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1214-1220.

14. Barnas C, Bergant A, Hummer M, et al. Clozapine concentrations in maternal and fetal plasma, amniotic fluid, and breast milk. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6):945.

15. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2013.

16. Lin H, Chen I, Chen Y, et al. Maternal schizophrenia and pregnancy outcome: does the use of antipsychotics make a difference? Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):55-60.

17. Young CR, Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(3):

381-390.

18. Zyprexa [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 1997.

19. Gilad O, Merlob P, Stahl B, et al. Outcome of infants exposed to olanzapine during breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):55-58.

20. Klier CM, Mossaheb N, Saria A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and elimination of quetiapine, venlafaxine, and trazodone during pregnancy and postpartum. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):720-722.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: quetiapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20639se1-017,016_seroquel_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

22. Coppola D, Russo LJ, Kwarta RF Jr, et al. Evaluating the postmarketing experience of risperidone use during pregnancy: pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Drug Saf. 2007;30(3):247-264.

23. Mackay FJ, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, et al. The safety of risperidone: a post-marketing study on 7,684 patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(6):413-418.

24. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: risperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020272s056,020588s044,021346s033,021444s03lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

26. Katz E, Adashi EY. Hyperprolactinemic disorders. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33(3):622-639.

27. Davis JR. Prolactin and reproductive medicine. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(4):331-337.

28. Johnson KC, Laprairie JL, Brennan PA, et al. Prenatal antipsychotic exposure and neuromotor performance during infancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):787-794. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.160.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: ziprasidone. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Advisory

Committees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Pediatric AdvisoryCommittee/UCM191883.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

30. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: lurasidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/200603Orig1s000PharmR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: asenapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022117s000_OtherR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

32. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: iloperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022192lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

33. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: paliperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021999s018lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

34. Weggelaar NM, Keijer WJ, Janssen PK. A case report of risperidone distribution and excretion into human milk: how to give good advice if you have not enough data available. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):129-131.

Although clinicians and patients generally are cautious when prescribing or using antipsychotics during pregnancy, inadequately controlled psychiatric illness poses risks to both mother and child. Calculating the risks and benefits of antipsychotic use during pregnancy is limited by an incomplete understanding of the true effectiveness and full spectrum of risks of these medications. Ethical principles prohibit the type of rigorous research that would be needed to achieve clarity on this issue. This article reviews studies that might help guide clinicians who are considering prescribing an atypical antipsychotic to manage psychiatric illness in a pregnant woman.

Antipsychotic efficacy in pregnancy

All atypical antipsychotics available in the United States are FDA-approved for treating schizophrenia; some also have been approved for treating bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, or symptoms associated with autism (Table 1). Atypical antipsychotics frequently are used off-label for these and other categories of psychiatric illness, including unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Studies of pharmacotherapy in pregnant women tend to focus more on safety rather than efficacy. Clinical decisions for an individual patient are best made based on knowledge about which medications have been effective for that patient in the past (Algorithm).

However, safety concerns in pregnancy may require modifying an existing regimen. In other cases, new symptoms arise during pregnancy and necessitate new medications. Additionally, a drug’s effectiveness may be affected by physiologic changes of pregnancy that can alter drug metabolism,1 potentially necessitating dose changes (Box 1).

Risks of treatment vs illness

Complete safety data on the use of any psychotropic medication during pregnancy are not available. To date, studies of atypical antipsychotics do not support any increased risk for congenital malformations large enough to be detected in medium-sized samples,2-4 although it is possible that there are increases in risk that are below the detection limit of these studies. Data regarding delivery outcomes are conflicting and difficult to interpret.

Several studies2-4 have yielded inconsistent results, including:

• risks for increased birth weight and large for gestational age3

• risks for low birth weight and small for gestational age2

• no significant differences from controls.4

Atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of gestational diabetes, whereas typical antipsychotics do not appear to increase this risk.4

Until recently, research has been limited by difficulties in separating the effects of treatment from the effects of psychiatric illness, which include intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, preterm birth, low Apgar scores, and congenital defects.5 In addition, most studies address early and easily measurable outcomes such as preterm labor, birth weight, and congenital malformations. Researchers are just beginning to investigate more subtle and long-term potential behavioral effects.

Several recent studies have explored outcomes associated with antipsychotic use during pregnancy while attempting to separate the effects of treatment from those of disease (Box 2).

Data on atypicals

Aripiprazole. Case reports of aripiprazole use during pregnancy have reported difficulties including transient unexplained fetal tachycardia that required emergent caesarean section6 and transient respiratory distress.7 Several small case series were not powered to detect risks related to aripiprazole.8,9

Animal data suggest teratogenic potential at dosages 3 and 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.10,11 Two studies7,12 that measured placental transfer of aripiprazole found cord-to-maternal serum concentration ratios ranging from 0.47 to 0.63, which is similar to the ratios for quetiapine and risperidone and lower than those for olanzapine and haloperidol.13

There are insufficient data to identify risks related to aripiprazole compared with other drugs in its class, and fewer reports are available than for other atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine and olanzapine. Placental transfer appears to be on the lower end of the spectrum for drugs in this class. Aripiprazole would be an acceptable choice for a woman who had a history of response to aripiprazole but likely would not be a first choice for a woman requiring a new medication during pregnancy.

Clozapine. In case reports, adverse effects associated with clozapine exposure during pregnancy include major malformations, gestational metabolic complications, poor pregnancy outcome, and perinatal adverse reactions. In one case, neonatal plasma clozapine concentrations were found to be twice that found in maternal plasma.14 Animal data have shown no evidence of increased teratogenicity at 2 to 4 times the maximum recommended human dosages.15 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with clozapine (11 exposures). Four other series2-4,16 were underpowered to detect concerns related specifically to clozapine.

There are insufficient data to identify risks related specifically to clozapine use during pregnancy. However, the rare but severe adverse effects associated with clozapine in other patient populations—including agranulocytosis and severe constipation17—could be devastating in a pregnant patient, which suggests this medication would not be a first-line treatment.

Olanzapine. In postmarketing surveillance studies and case reports, there have been have anecdotal cases of fetal malformations related to olanzapine use during pregnancy. Several larger studies2-4,8,16 did not find higher rates of congenital malformations or any pattern of malformation types, although none were designed or powered to examine rare events. Animal data show no evidence of teratogenicity.18 A study comparing rates of placental passage of antipsychotics13 found higher rates for olanzapine than for quetiapine and risperidone, as well as higher prevalence of low birth weight and perinatal complications. A neonatal withdrawal syndrome has also been reported.19 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with olanzapine.

Data suggest that olanzapine may be associated with somewhat higher rates of the adverse effects attributable to atypical antipsychotics (gestational diabetes and possibly macrocephaly), which could be related to olanzapine’s relatively higher rate of placental passage. Olanzapine could be a reasonable choice in a woman who had a history of good response to this medication, but would be lower priority than quetiapine when a new drug is indicated during pregnancy.

Quetiapine. In clinical trials, quetiapine had lower rates of placental passage compared with risperidone and olanzapine.13 One case report found only small changes in quetiapine serum levels during pregnancy.20 Prospective studies (90 exposures,8 36 exposures,2 7 exposures,16 4 exposures,3 and 4 exposures4) show no increase in fetal malformations or adverse neonatal health outcomes related to quetiapine, and manufacturer safety data reveal no teratogenic effect, although delays in fetal skeletal ossification were seen in rats and rabbits at doses comparable to the recommended human range.21

Quetiapine is a reasonable first choice when a new atypical antipsychotic is indicated for a pregnant patient.

Risperidone. Rates of placental passage of risperidone are higher compared with quetiapine.13 Postmarketing surveillance data (265 exposures22 and 10 exposures23) and prospective studies (including 72 exposures,8 49 exposures,2 51 exposures,4 16 exposures,16 and 5 exposures3) suggest risperidone has no major teratogenic effect. When malformations were present, they were similar to expected rates and types of malformations, and no specific malformation type was overrepresented. However, in some cases, researchers noted a withdrawal-emergent syndrome that included various combinations of tremors, irritability, poor feeding, and somnolence.22 Animal data are similarly reassuring, although increases in early fetal mortality and (potentially related) changes in maternal behavior have been observed in rats.24,25 A major caveat with risperidone is its propensity to cause hyperprolactinemia, which is detrimental to efforts to conceive and maintain a pregnancy.26,27

Risperidone is not associated with higher rates of adverse events in pregnancy than other atypical antipsychotics. It would not be a first choice for a woman trying to conceive or in the early stages of pregnancy, but would be a reasonable choice for a woman already well into pregnancy.

Ziprasidone. Available reports are few and generally do not report findings on ziprasidone separately.8,28 Manufacturer data includes 5 spontaneous abortions, one malformation, and one stillbirth among 57 exposures,4 and available animal data suggest significant developmental toxicity and impaired fertility.29 In pregnant rats, ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.5 times the maximum human recommended dose resulted in delayed fetal skeletal ossification, increased stillbirths, and decreased fetal weight and postnatal survival, and ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.2 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in developmental delays and neurobehavioral impairments in offspring. In pregnant rabbits, ziprasidone dosed at 3 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in cardiac and renal malformations.29

Although available data are too sparse to draw reliable conclusions, the small amount of human data plus animal data suggest that ziprasidone should be less preferred than other atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Lurasidone. No data addressing lurasidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Material submitted to the FDA includes no evidence of teratogenicity or embryo-fetal toxicity in rat and rabbit studies using 3 and 12 times the maximum recommended human dose (80 mg) based on a body surface area comparison.30

Asenapine. No data specifically addressing asenapine use in humans during pregnancy are available. Studies in rats and rabbits found no increase in teratogenicity, but did find increases in postimplantation loss and decreases in pup survival and weight gain with maternal doses equivalent to less than the maximum recommended human dose.31

Iloperidone. No data specifically addressing iloperidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Animal studies of iloperidone found multiple developmental toxicities when iloperidone was administered during gestation.32 In one study, pregnant rats were given up to 26 times the maximum recommended human dose of 24 mg/d during the period of organogenesis. The highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths, decreased fetal weight and length, decreased fetal skeletal ossification, and increased minor fetal skeletal anomalies and variations. In a similar study using pregnant rabbits, the highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths and decreased fetal viability at term.

Paliperidone. In animal studies, there were no increases in fetal abnormalities when pregnant rats and rabbits were treated with up to 8 times the maximum recommended human dose of paliperidone during the period of organogenesis.33

A single case report34 measured levels of risperidone and its 9-hydroxy metabolite, paliperidone, in the breast milk of a mother who had taken risperidone during pregnancy and in the serum of her child. 9-OH-risperidone dose in breast milk was calculated as 4.7% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose, and serum levels in the infant were undetectable. No ill effects on the child were observed.

It is not possible to draw solid conclusions about atypical antipsychotics’ potential effects on human development from animal studies. Because of the lack of human data for the newer atypical antipsychotics—asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, paliperidone—in general these agents would not be advisable as first-line medications for treating pregnant women.

A few caveats

All atypical antipsychotics share the propensity to trigger or worsen glucose intolerance, which can have significant negative consequences in a pregnant patient. When deciding to use an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy, blood glucose should be monitored carefully and regularly.

Because all atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) are FDA pregnancy class C—indicating that animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks—the decision to use these medications must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits. Patients and their providers together should make a fully informed decision.

There is an urgent need for larger and better-designed investigations that will be sufficiently powered to detect differences in outcomes—particularly major malformations, preterm delivery, adverse events in labor and delivery, metabolic and anthropometric effects on the newborn, and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric outcomes for individuals exposed in utero—between women without mental illness, untreated women with mental illness, and women receiving atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy. Further research into the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of antipsychotics in pregnant women also would be useful. Clinicians can assist with these efforts by submitting their patient data to a pregnancy registry maintained by the Massachusetts General Hospital (see Related Resources).

Bottom Line

Treatment with atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy may increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes, but inadequately controlled mental illness also carries some degree of risk. The decision to use any atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits and made by the pregnant patient and her provider.

Related Resources

- Gentile S. Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):518-544. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879689.

- Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. www.womensmentalhealth.org/clinical-and-research-programs/pregnancyregistry.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Asenapine • Saphris Paliperidone • Invega

Clozapine • Clozaril Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Iloperidone • Fanapt Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lurasidone • Latuda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Although clinicians and patients generally are cautious when prescribing or using antipsychotics during pregnancy, inadequately controlled psychiatric illness poses risks to both mother and child. Calculating the risks and benefits of antipsychotic use during pregnancy is limited by an incomplete understanding of the true effectiveness and full spectrum of risks of these medications. Ethical principles prohibit the type of rigorous research that would be needed to achieve clarity on this issue. This article reviews studies that might help guide clinicians who are considering prescribing an atypical antipsychotic to manage psychiatric illness in a pregnant woman.

Antipsychotic efficacy in pregnancy

All atypical antipsychotics available in the United States are FDA-approved for treating schizophrenia; some also have been approved for treating bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, or symptoms associated with autism (Table 1). Atypical antipsychotics frequently are used off-label for these and other categories of psychiatric illness, including unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Studies of pharmacotherapy in pregnant women tend to focus more on safety rather than efficacy. Clinical decisions for an individual patient are best made based on knowledge about which medications have been effective for that patient in the past (Algorithm).

However, safety concerns in pregnancy may require modifying an existing regimen. In other cases, new symptoms arise during pregnancy and necessitate new medications. Additionally, a drug’s effectiveness may be affected by physiologic changes of pregnancy that can alter drug metabolism,1 potentially necessitating dose changes (Box 1).

Risks of treatment vs illness

Complete safety data on the use of any psychotropic medication during pregnancy are not available. To date, studies of atypical antipsychotics do not support any increased risk for congenital malformations large enough to be detected in medium-sized samples,2-4 although it is possible that there are increases in risk that are below the detection limit of these studies. Data regarding delivery outcomes are conflicting and difficult to interpret.

Several studies2-4 have yielded inconsistent results, including:

• risks for increased birth weight and large for gestational age3

• risks for low birth weight and small for gestational age2

• no significant differences from controls.4

Atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of gestational diabetes, whereas typical antipsychotics do not appear to increase this risk.4

Until recently, research has been limited by difficulties in separating the effects of treatment from the effects of psychiatric illness, which include intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, preterm birth, low Apgar scores, and congenital defects.5 In addition, most studies address early and easily measurable outcomes such as preterm labor, birth weight, and congenital malformations. Researchers are just beginning to investigate more subtle and long-term potential behavioral effects.

Several recent studies have explored outcomes associated with antipsychotic use during pregnancy while attempting to separate the effects of treatment from those of disease (Box 2).

Data on atypicals

Aripiprazole. Case reports of aripiprazole use during pregnancy have reported difficulties including transient unexplained fetal tachycardia that required emergent caesarean section6 and transient respiratory distress.7 Several small case series were not powered to detect risks related to aripiprazole.8,9

Animal data suggest teratogenic potential at dosages 3 and 10 times the maximum recommended human dose.10,11 Two studies7,12 that measured placental transfer of aripiprazole found cord-to-maternal serum concentration ratios ranging from 0.47 to 0.63, which is similar to the ratios for quetiapine and risperidone and lower than those for olanzapine and haloperidol.13

There are insufficient data to identify risks related to aripiprazole compared with other drugs in its class, and fewer reports are available than for other atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine and olanzapine. Placental transfer appears to be on the lower end of the spectrum for drugs in this class. Aripiprazole would be an acceptable choice for a woman who had a history of response to aripiprazole but likely would not be a first choice for a woman requiring a new medication during pregnancy.

Clozapine. In case reports, adverse effects associated with clozapine exposure during pregnancy include major malformations, gestational metabolic complications, poor pregnancy outcome, and perinatal adverse reactions. In one case, neonatal plasma clozapine concentrations were found to be twice that found in maternal plasma.14 Animal data have shown no evidence of increased teratogenicity at 2 to 4 times the maximum recommended human dosages.15 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with clozapine (11 exposures). Four other series2-4,16 were underpowered to detect concerns related specifically to clozapine.

There are insufficient data to identify risks related specifically to clozapine use during pregnancy. However, the rare but severe adverse effects associated with clozapine in other patient populations—including agranulocytosis and severe constipation17—could be devastating in a pregnant patient, which suggests this medication would not be a first-line treatment.

Olanzapine. In postmarketing surveillance studies and case reports, there have been have anecdotal cases of fetal malformations related to olanzapine use during pregnancy. Several larger studies2-4,8,16 did not find higher rates of congenital malformations or any pattern of malformation types, although none were designed or powered to examine rare events. Animal data show no evidence of teratogenicity.18 A study comparing rates of placental passage of antipsychotics13 found higher rates for olanzapine than for quetiapine and risperidone, as well as higher prevalence of low birth weight and perinatal complications. A neonatal withdrawal syndrome has also been reported.19 Boden et al8 found an increased risk for gestational diabetes and macrocephaly with olanzapine.

Data suggest that olanzapine may be associated with somewhat higher rates of the adverse effects attributable to atypical antipsychotics (gestational diabetes and possibly macrocephaly), which could be related to olanzapine’s relatively higher rate of placental passage. Olanzapine could be a reasonable choice in a woman who had a history of good response to this medication, but would be lower priority than quetiapine when a new drug is indicated during pregnancy.

Quetiapine. In clinical trials, quetiapine had lower rates of placental passage compared with risperidone and olanzapine.13 One case report found only small changes in quetiapine serum levels during pregnancy.20 Prospective studies (90 exposures,8 36 exposures,2 7 exposures,16 4 exposures,3 and 4 exposures4) show no increase in fetal malformations or adverse neonatal health outcomes related to quetiapine, and manufacturer safety data reveal no teratogenic effect, although delays in fetal skeletal ossification were seen in rats and rabbits at doses comparable to the recommended human range.21

Quetiapine is a reasonable first choice when a new atypical antipsychotic is indicated for a pregnant patient.

Risperidone. Rates of placental passage of risperidone are higher compared with quetiapine.13 Postmarketing surveillance data (265 exposures22 and 10 exposures23) and prospective studies (including 72 exposures,8 49 exposures,2 51 exposures,4 16 exposures,16 and 5 exposures3) suggest risperidone has no major teratogenic effect. When malformations were present, they were similar to expected rates and types of malformations, and no specific malformation type was overrepresented. However, in some cases, researchers noted a withdrawal-emergent syndrome that included various combinations of tremors, irritability, poor feeding, and somnolence.22 Animal data are similarly reassuring, although increases in early fetal mortality and (potentially related) changes in maternal behavior have been observed in rats.24,25 A major caveat with risperidone is its propensity to cause hyperprolactinemia, which is detrimental to efforts to conceive and maintain a pregnancy.26,27

Risperidone is not associated with higher rates of adverse events in pregnancy than other atypical antipsychotics. It would not be a first choice for a woman trying to conceive or in the early stages of pregnancy, but would be a reasonable choice for a woman already well into pregnancy.

Ziprasidone. Available reports are few and generally do not report findings on ziprasidone separately.8,28 Manufacturer data includes 5 spontaneous abortions, one malformation, and one stillbirth among 57 exposures,4 and available animal data suggest significant developmental toxicity and impaired fertility.29 In pregnant rats, ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.5 times the maximum human recommended dose resulted in delayed fetal skeletal ossification, increased stillbirths, and decreased fetal weight and postnatal survival, and ziprasidone dosed as low as 0.2 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in developmental delays and neurobehavioral impairments in offspring. In pregnant rabbits, ziprasidone dosed at 3 times the maximum recommended human dose resulted in cardiac and renal malformations.29

Although available data are too sparse to draw reliable conclusions, the small amount of human data plus animal data suggest that ziprasidone should be less preferred than other atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Lurasidone. No data addressing lurasidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Material submitted to the FDA includes no evidence of teratogenicity or embryo-fetal toxicity in rat and rabbit studies using 3 and 12 times the maximum recommended human dose (80 mg) based on a body surface area comparison.30

Asenapine. No data specifically addressing asenapine use in humans during pregnancy are available. Studies in rats and rabbits found no increase in teratogenicity, but did find increases in postimplantation loss and decreases in pup survival and weight gain with maternal doses equivalent to less than the maximum recommended human dose.31

Iloperidone. No data specifically addressing iloperidone use in humans during pregnancy are available. Animal studies of iloperidone found multiple developmental toxicities when iloperidone was administered during gestation.32 In one study, pregnant rats were given up to 26 times the maximum recommended human dose of 24 mg/d during the period of organogenesis. The highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths, decreased fetal weight and length, decreased fetal skeletal ossification, and increased minor fetal skeletal anomalies and variations. In a similar study using pregnant rabbits, the highest dose caused increased early intrauterine deaths and decreased fetal viability at term.

Paliperidone. In animal studies, there were no increases in fetal abnormalities when pregnant rats and rabbits were treated with up to 8 times the maximum recommended human dose of paliperidone during the period of organogenesis.33

A single case report34 measured levels of risperidone and its 9-hydroxy metabolite, paliperidone, in the breast milk of a mother who had taken risperidone during pregnancy and in the serum of her child. 9-OH-risperidone dose in breast milk was calculated as 4.7% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose, and serum levels in the infant were undetectable. No ill effects on the child were observed.

It is not possible to draw solid conclusions about atypical antipsychotics’ potential effects on human development from animal studies. Because of the lack of human data for the newer atypical antipsychotics—asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, paliperidone—in general these agents would not be advisable as first-line medications for treating pregnant women.

A few caveats

All atypical antipsychotics share the propensity to trigger or worsen glucose intolerance, which can have significant negative consequences in a pregnant patient. When deciding to use an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy, blood glucose should be monitored carefully and regularly.

Because all atypical antipsychotics (except clozapine) are FDA pregnancy class C—indicating that animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks—the decision to use these medications must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits. Patients and their providers together should make a fully informed decision.

There is an urgent need for larger and better-designed investigations that will be sufficiently powered to detect differences in outcomes—particularly major malformations, preterm delivery, adverse events in labor and delivery, metabolic and anthropometric effects on the newborn, and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric outcomes for individuals exposed in utero—between women without mental illness, untreated women with mental illness, and women receiving atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy. Further research into the pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of antipsychotics in pregnant women also would be useful. Clinicians can assist with these efforts by submitting their patient data to a pregnancy registry maintained by the Massachusetts General Hospital (see Related Resources).

Bottom Line

Treatment with atypical antipsychotics during pregnancy may increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes, but inadequately controlled mental illness also carries some degree of risk. The decision to use any atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy must be based on an individualized assessment of risks and benefits and made by the pregnant patient and her provider.

Related Resources

- Gentile S. Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):518-544. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879689.

- Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics. www.womensmentalhealth.org/clinical-and-research-programs/pregnancyregistry.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Asenapine • Saphris Paliperidone • Invega

Clozapine • Clozaril Quetiapine • Seroquel

Haloperidol • Haldol Risperidone • Risperdal

Iloperidone • Fanapt Ziprasidone • Geodon

Lurasidone • Latuda

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Chang J, Streitman D. Physiologic adaptations to pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2012;30(3):781-789.

2. McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4): 444-449; quiz 546.

3. Newham JJ, Thomas SH, MacRitchie K, et al. Birth weight of infants after maternal exposure to typical and atypical antipsychotics: prospective comparison study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):333-337.

4. Reis M, Kallen B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):279-288.

5. Matevosyan NR. Pregnancy and postpartum specifics in women with schizophrenia: a meta-study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(2):141-147.

6. Mendhekar DN, Sunder KR, Andrade C. Aripiprazole use in a pregnant schizoaffective woman. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):299-300.

7. Watanabe N, Kasahara M, Sugibayashi R, et al. Perinatal use of aripiprazole: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):377-379.

8. Bodén R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, et al. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):715-721.

9. Maáková E, Hubicˇková L. Antidepressant drug exposure during pregnancy. CZTIS small prospective study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2011;32(suppl 1):53-56.

10. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Ed.). Aripiprazole: Drugdex drug evaluations, 1974-2003. Princeton, NJ: Thomson Micromedex; 2003.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: Aripiprazole. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/21436slr006_abilify_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

12. Nguyen T, Teoh S, Hackett LP, et al. Placental transfer of aripiprazole. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):500-501.

13. Newport DJ, Calamaras MR, DeVane CL, et al. Atypical antipsychotic administration during late pregnancy: placental passage and obstetrical outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1214-1220.

14. Barnas C, Bergant A, Hummer M, et al. Clozapine concentrations in maternal and fetal plasma, amniotic fluid, and breast milk. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6):945.

15. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2013.

16. Lin H, Chen I, Chen Y, et al. Maternal schizophrenia and pregnancy outcome: does the use of antipsychotics make a difference? Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):55-60.

17. Young CR, Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(3):

381-390.

18. Zyprexa [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 1997.

19. Gilad O, Merlob P, Stahl B, et al. Outcome of infants exposed to olanzapine during breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):55-58.

20. Klier CM, Mossaheb N, Saria A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and elimination of quetiapine, venlafaxine, and trazodone during pregnancy and postpartum. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):720-722.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: quetiapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20639se1-017,016_seroquel_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

22. Coppola D, Russo LJ, Kwarta RF Jr, et al. Evaluating the postmarketing experience of risperidone use during pregnancy: pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Drug Saf. 2007;30(3):247-264.

23. Mackay FJ, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, et al. The safety of risperidone: a post-marketing study on 7,684 patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(6):413-418.

24. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: risperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020272s056,020588s044,021346s033,021444s03lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

26. Katz E, Adashi EY. Hyperprolactinemic disorders. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33(3):622-639.

27. Davis JR. Prolactin and reproductive medicine. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(4):331-337.

28. Johnson KC, Laprairie JL, Brennan PA, et al. Prenatal antipsychotic exposure and neuromotor performance during infancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):787-794. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.160.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: ziprasidone. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Advisory

Committees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Pediatric AdvisoryCommittee/UCM191883.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

30. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: lurasidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/200603Orig1s000PharmR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: asenapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022117s000_OtherR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

32. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: iloperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022192lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

33. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: paliperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021999s018lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

34. Weggelaar NM, Keijer WJ, Janssen PK. A case report of risperidone distribution and excretion into human milk: how to give good advice if you have not enough data available. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):129-131.

1. Chang J, Streitman D. Physiologic adaptations to pregnancy. Neurol Clin. 2012;30(3):781-789.

2. McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4): 444-449; quiz 546.

3. Newham JJ, Thomas SH, MacRitchie K, et al. Birth weight of infants after maternal exposure to typical and atypical antipsychotics: prospective comparison study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(5):333-337.

4. Reis M, Kallen B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):279-288.

5. Matevosyan NR. Pregnancy and postpartum specifics in women with schizophrenia: a meta-study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(2):141-147.

6. Mendhekar DN, Sunder KR, Andrade C. Aripiprazole use in a pregnant schizoaffective woman. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):299-300.

7. Watanabe N, Kasahara M, Sugibayashi R, et al. Perinatal use of aripiprazole: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):377-379.

8. Bodén R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, et al. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):715-721.

9. Maáková E, Hubicˇková L. Antidepressant drug exposure during pregnancy. CZTIS small prospective study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2011;32(suppl 1):53-56.

10. Bristol-Myers Squibb (Ed.). Aripiprazole: Drugdex drug evaluations, 1974-2003. Princeton, NJ: Thomson Micromedex; 2003.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: Aripiprazole. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/21436slr006_abilify_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

12. Nguyen T, Teoh S, Hackett LP, et al. Placental transfer of aripiprazole. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):500-501.

13. Newport DJ, Calamaras MR, DeVane CL, et al. Atypical antipsychotic administration during late pregnancy: placental passage and obstetrical outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1214-1220.

14. Barnas C, Bergant A, Hummer M, et al. Clozapine concentrations in maternal and fetal plasma, amniotic fluid, and breast milk. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6):945.

15. Clozaril [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2013.

16. Lin H, Chen I, Chen Y, et al. Maternal schizophrenia and pregnancy outcome: does the use of antipsychotics make a difference? Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):55-60.

17. Young CR, Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM. Management of the adverse effects of clozapine. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(3):

381-390.

18. Zyprexa [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 1997.

19. Gilad O, Merlob P, Stahl B, et al. Outcome of infants exposed to olanzapine during breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):55-58.

20. Klier CM, Mossaheb N, Saria A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and elimination of quetiapine, venlafaxine, and trazodone during pregnancy and postpartum. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):720-722.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: quetiapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/20639se1-017,016_seroquel_lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

22. Coppola D, Russo LJ, Kwarta RF Jr, et al. Evaluating the postmarketing experience of risperidone use during pregnancy: pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Drug Saf. 2007;30(3):247-264.

23. Mackay FJ, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, et al. The safety of risperidone: a post-marketing study on 7,684 patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(6):413-418.

24. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: risperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020272s056,020588s044,021346s033,021444s03lbl.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2013.

26. Katz E, Adashi EY. Hyperprolactinemic disorders. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33(3):622-639.

27. Davis JR. Prolactin and reproductive medicine. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(4):331-337.

28. Johnson KC, Laprairie JL, Brennan PA, et al. Prenatal antipsychotic exposure and neuromotor performance during infancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):787-794. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.160.

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: ziprasidone. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Advisory

Committees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Pediatric AdvisoryCommittee/UCM191883.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

30. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: lurasidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/200603Orig1s000PharmR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: asenapine. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022117s000_OtherR.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

32. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: iloperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022192lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

33. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA datasheet: paliperidone. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021999s018lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

34. Weggelaar NM, Keijer WJ, Janssen PK. A case report of risperidone distribution and excretion into human milk: how to give good advice if you have not enough data available. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):129-131.