User login

Professional societies, global organizations, and advocacy groups are continually working toward the goal of having the costs of infertility care covered by insurance carriers. Paramount to that effort is obtaining recognition of infertility as a burdensome disease. In this Update, we summarize national and international initiatives and societal trends that are helping to move us closer to that goal, and we encourage ObGyns to lead advocacy efforts.

Next, we detail several notable new features available in the annual report of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), an online interactive document that can be used to assist clinicians and patients in treatment decisions.

We also tackle the complexities of embryo selection for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and describe a potentially promising aneuploidy screening test, and explore its limitations.

Advances in recognizing infertility as a disease that merits insurance coverage

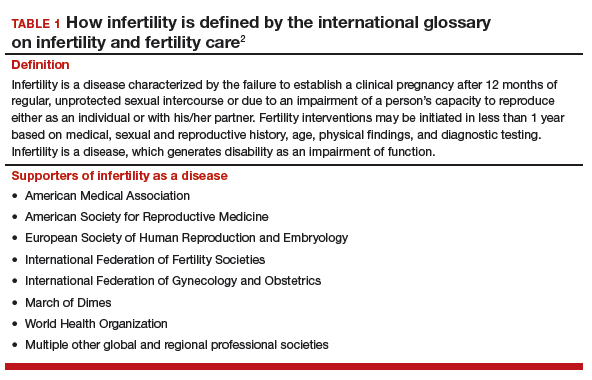

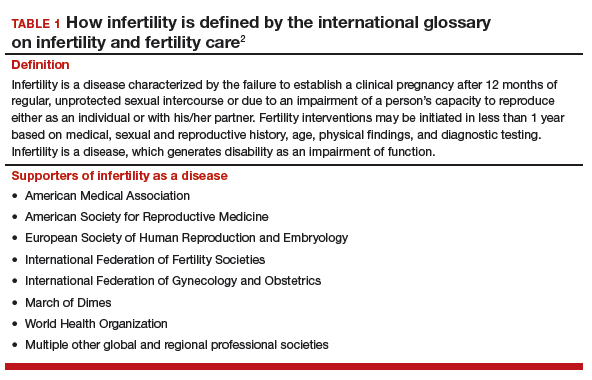

Major reproductive medicine organizations globally have endorsed the definition of infertility as a disease that "generates disability as an impairment of function" (TABLE 1).2 Fortunately, medical, societal, and judicial changes have resulted in progress for the 6.1 million women (and equivalent number of men) affected by infertility in the United States.3

Professional group advocacy efforts, and judicial rulings

The World Health Organization (WHO) has addressed infertility over the past several decades, with the organization's standards on semen analysis being the most recognized outcome. Progress has been limited, however, regarding global or national policy that recognizes the importance of infertility as a medical and public health problem.

In 2009, the glossary published by the WHO with the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) defined infertility as a disease.4 This recognition is important because it aids policy making, insurance coverage, and/or other payments for services.

The WHO also has begun the process of developing new infertility guidelines. Recently, the WHO held a summit on safety and access to fertility care, which was attended by many representatives of nation-state governments and international experts. It is hoped that a document from those proceedings will reinforce the public health importance of infertility and support the need to promote equality in access to safe fertility care. WHO initiatives matter because they apply to nation-states.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) for many years has recognized infertility as a disease. Only in 2017, however, did delegates at the American Medical Association's annual meeting vote to support the WHO's designation of infertility as a disease.

Continue to: Judicial views

Judicial views. In 1998, the US Supreme Court held that infertility is a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The Court subsequently held, however, that a person is not considered disabled under the act if the disability can be overcome by mitigating or corrective measures. In 2000, a lower court held that, while infertility is a disability, an employer's health plan that excludes treatment for it is not discriminatory under the ADA if it applies to all employees.

Societal recognition. Interestingly, improved technology for oocyte cryopreservation has resulted in greater recognition of reproductive issues and the disparity in reproductive health societal norms and rights between men and women.

Media stories and gender issues in employment, especially in such high-profile industries as technology and finance, have highlighted long-standing inequities, many of which concern reproductive issues. These issues have been further disseminated by the #metoo movement. Some employers are beginning to respond by recognizing their employees' reproductive needs and providing improved benefits for reproductive care.

ObGyns must continue to lead advocacy

Not all has been progress. Personhood bills in several states threaten basic reproductive rights of women and men. The ASRM and Resolve (the National Infertility Association) have taken leading roles in opposing these legislative initiatives and supporting reproductive rights.5

Advocacy efforts through events and trends have resulted in gradually improving the recognition of the burden of infertility, inadequate insurance coverage, and continuing gender inequalities in reproduction. Today, patients, professionals, and national and international organizations are coalescing around demands for recognition, access to care, and gender and diversity equality. While much remains to be done, progress is being made in society, government, the workplace, and the health care system.

ObGyns and other women's health care providers can help continue the progress toward equality in reproductive rights, including access to infertility care, by discussing insurance inequities with patients, informing insurance companies that infertility is a disease, and encouraging patients to challenge inadequate and unequal insurance coverage of needed reproductive health care.

The time is now for ObGyns and other women’s health care providers to advocate for insurance coverage of infertility care. When our patients have inadequate coverage, we should encourage them to take action by contacting their insurance company and their employers to explain the reasons and argue for better coverage. Also, contact RESOLVE for additional information.

Latest SART report offers new features to aid in treatment decision making

Knowledge of the prognosis and its various treatment options is an important aspect of infertility treatment. The SART recently updated its annual Clinic Summary Report (CSR), which includes valuable new features for patients and physicians considering assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment.6

SART compiles complex data and reports outcomes

The SART has been reporting IVF outcomes and other ART outcomes since 1988. The society's annual report is widely read by consumers, patients, physicians, and policy makers, and it has many important uses. However, the report is complicated and difficult to interpret for many reasons. For example, treatments are complex and varied (especially with application of new cryopreservation technology), and there are variations among clinics with respect to patient selection, protocols used, philosophy of practice, and numerous other variables.

Continue to: Because of this...

Because of this, the SART states, "The SART Clinic Summary Report (CSR) allows patients to view national and individual clinic IVF success rates. The data presented in this report should not be used for comparing clinics. Clinics may have differences in patient selection and treatment approaches which may artificially inflate or lower pregnancy rates relative to another clinic. Please discuss this with your doctor."6

Nevertheless, the CSR is extremely useful because it reports outcomes, which can lead to more informed patients and physicians and thus better access to safe and effective use of ART. The SART has redesigned the CSR to make it more useful.

Redesigned CSR focuses on outcomes important to patients

In recent years, new technologies have increased dramatically the use of embryo cryopreservation, genetic testing, and single embryo transfer (SET). The new CSR format is more patient focused and identifies more directly the treatment burden: ovarian stimulation, egg retrieval, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), cryopreservation, frozen embryo transfer, and multiple cycles. It also focuses on the important patient outcomes, including live birth of a healthy child, multiple pregnancy, number of cycles, and chances of success per patient over time (including both fresh and frozen embryo transfers).

Notable changes

A major change in the CSR is that there is a preliminary report for a given year and then a final report the following year. This helps to more accurately report cycles that have been "delayed" because of egg retrieval and embryo freezing performed in the reported year but then transferred in the following reporting year.

Cycle counting. A cycle is counted when a woman has started medications for an ART procedure or, in a "natural" cycle when no medications are used, the first day of menses of the ART cycle. If several cycles are performed to bank eggs or embryos, each will be counted in the denominator when calculating the pregnancy rate. This more accurately reflects the patient treatment burden and costs. A cycle cancelled before egg retrieval is still counted as a cycle.

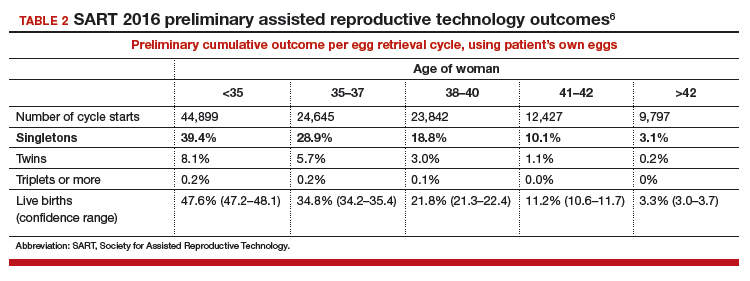

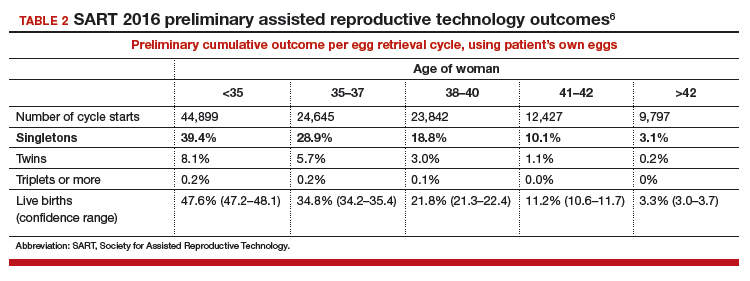

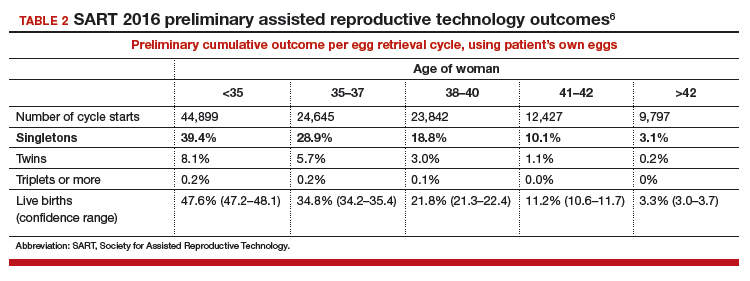

Defining success. Success is characterized as delivery of a child, since this is the outcome patients desire. Singleton deliveries are emphasized, since twin and higher-order multiple pregnancies have a higher risk of prematurity, morbidity, mortality, and cost. The percentages of triplet, twin, and singleton births contributing to the live birth rate are provided for each cycle group, as is prematurity (TABLE 2).6

The end point of a treatment cycle can vary. The new CSR captures the success rate following one or more egg retrievals and the first embryo transfer (primary outcome), the success of subsequent cycles using frozen eggs or embryos not transferred in the first embryo transfer, and the combined contribution of the primary and subsequent cycles to the cumulative live birth rate for a patient both in the preliminary report and the final report for any given year. The live birth rate per patient also is reported and includes the outcomes for patients who are new to an infertility center and starting their first cycle for retrieval of their own eggs during the reporting year.

Continue to: Outcomes and prognostic factors...

Outcomes and prognostic factors. Outcomes are reported by multiple factors, including patient age and source of the eggs. These are important prognostic factors; separating the data allows you to obtain a better idea of both national and individual clinic experience by these factors.

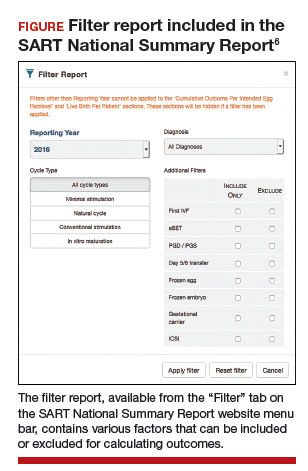

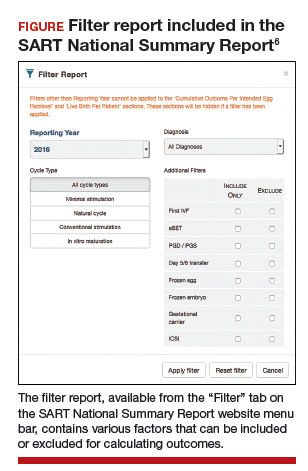

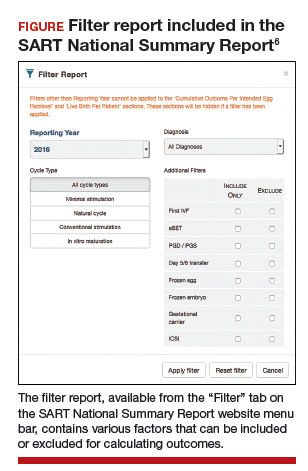

The CSR also contains filters for infertility diagnosis, stimulation type, and other treatment details (FIGURE).6 The filter is a useful feature because multiple types of treatment can be included or excluded. The outcome of different treatment interventions can then be estimated based on outcomes from the entire sample of US patients with similar characteristics and interventions. This powerful tool can help patients and physicians choose the best treatment based on prognosis.

Personalized prognosis. An important new feature is the SART Patient Predictor (https://www.sartcorsonline.com/predictor/patient), a model that permits an individual patient to obtain a more personalized prognosis. While the SART predictor uses only basic patient information, such as age, body mass index, and diagnosis, its estimate is based on the entire US sample of reported ART experience and therefore can help patients in decision making. Furthermore, the predictor calculates percentages for the outcome of one transfer of 2 embryos, and 2 transfers of a single embryo, to demonstrate the advantages of SET that result in a higher live birth rate but a significantly lower multiple pregnancy rate.

Summing up

The SART's new CSR is extremely useful to patients and to any physician who cares for infertility patients. It can help users both understand the expected results from different ART treatments and enable better physician-patient communication and decision making.

The updated annual SART Clinic Summary Report is an exceptionally valuable and easy-to-use online tool for you and your infertility patients.

Embryo selection techniques refined with use of newer technologies

Since the introduction of IVF in 1978, the final cumulative live birth rates per cycle initiated for oocyte retrieval after all resulting embryos have been trasferred continue to rise, currently standing at 54% for women younger than age 35 in the United States.7 A number of achievements have contributed to this remarkable success, namely, improvements in IVF laboratory and embryo culture systems, advances in cryopreservation technology, availability of highly effective gonadotropins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, improved ultrasound technology, and the introduction of soft catheters for atraumatic embryo transfers.

Treatment now focuses on improved embryo selection

Now that excellent success rates have been attained, the focus of optimizing efforts in fertility treatment has shifted to improving safety by reducing the rates of multiple pregnancy through elective single embryo transfer (eSET), reducing the rates of miscarriage, and shortening the time to live birth. Methods to improve embryo selection lie at the forefront of these initiatives. These vary and include extended culture to blastocyst stage, standard morphologic evaluation as well as morphokinetic assessment of embryonic development via time-lapse imaging, and more recently the reintroduction of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), formerly known as preimplantation genetic screening (PGS).

Chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo, or embryo aneuploidies, are the most common cause of treatment failure following embryo transfer in IVF. The proportion of embryos affected with aneuploidies significantly increases with advancing maternal age: 40% to 50% of blastocysts in women younger than age 35 and about 90% of blastocysts in women older than age 42.8 The premise with PGT-A is to identify these aneuploid embryos and increase the chances of success per embryo transfer by transferring euploid embryos.

Continue to: That concept was initially applied...

That concept was initially applied to cleavage-stage embryos through the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology to interrogate a maximum of 5 to 9 chromosomes in a single cell (single blastomere); however, although initial results from observational studies were encouraging, subsequent randomized controlled studies unexpectedly showed a reduction in pregnancy rates.9 This was attributed to several factors, including biopsy-related damage to the cleavage-stage embryo, inability of FISH technology to assess aneuploidies of more than 5 to 9 chromosomes, mosaicism, and technical limitations associated with single-cell analysis.

Second-generation PGT-A testing has promise, and limitations

The newer PGT-A tests the embryos at the blastocyst stage by using biopsy samples from the trophectoderm (which will form the future placenta); this is expected to spare the inner cell mass ([ICM] which will give rise to the embryo proper) from biopsy-related injury.

On the genetics side, newer technologies, such as array comparative genomic hybridization, single nucleotide polymorphism arrays, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and next-generation sequencing, offer the opportunity to assess all 24 chromosomes in a single biopsy specimen. Although a detailed discussion of these testing platforms is beyond the scope of this Update, certain points are worth mentioning. All these technologies require some form of genetic material amplification (most commonly whole genome amplification or multiplex polymerase chain reaction) to increase the relatively scant amount of DNA obtained from a sample of 4 to 6 cells. These amplification techniques have limitations that can subsequently impact the validity of the test results.

Furthermore, there is no consistency in depth of coverage for various parts of the genome, and subchromosomal (segmental) copy number variations below 3 to 5 Mb may not be detected. The threshold used in bioinformatics algorithms employed to interpret the raw data is subject to several biases and is not consistent among laboratories. As a result, the same sample assessed in different laboratories can potentially yield different results.

In addition to these technical limitations, mosaicism can pose another biologic limitation, as the biopsied trophectoderm cells may not accurately represent the chromosomal makeup of the ICM. Also, an embryo may be able to undergo self-correction during subsequent stages of development, and therefore even a documented trophectoderm abnormality at the blastocyst stage may not necessarily preclude that embryo from developing into a healthy baby.

Standardization is needed. Despite widespread promotion of PGT-A, well-designed randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have not yet consistently shown its benefits in improving pregnancy rates or reducing miscarriage rates. Although the initial small RCTs in a selected group of good prognosis patients suggested a beneficial effect in ongoing pregnancy rates per transfer, the largest multicenter RCT to date did not show any improvement in pregnancy rates or reduction in miscarriage rates.10 In that study, a post hoc subgroup analysis suggested a possible beneficial effect in women aged 35 to 40. However, those results must be validated and reproduced with randomization at the start of stimulation, with the primary outcome being the live birth rate per initiated cycle, instead of per transfer, before PGT-A can be adopted universally in clinical practice.

Continue to: With all the above considerations...

With all the above considerations, the ASRM has appropriately concluded that "the value of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) as a screening test for IVF patients has yet to be determined."11

Standardization of clinical and laboratory protocols and additional studies to assess the effects of PGT-A on live birth rates per initiated cycles are recommended before this new technology is widely adopted in routine clinical practice. In our practice, we routinely offer and perform extended culture to blastocyst stage and standard morphologic assessment. After a thorough counseling on the current status of PGT-A, about 15% to 20% of our patients opt to undergo PGT-A.

- United Nations website. General Assembly resolution 217A: Declaration of human rights. December 10, 1948. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declara tion-human-rights/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:393-406.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women's Health website. Infertility. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/infertility. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology, World Health Organization. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1520-1524.

- RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association website. Opposing personhood: Resolve fights to keep fertility medical treatments legal in the US. https://resolve.org/get-involved/advocate-for-access/our-issues/opposing-personhood/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report. 2016 Preliminary national data. https://www.sartcorsonline.com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx?reportingYear=2016 . Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report 2015. https://www.sartcorsonline,com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx ?reportingYear=2015. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Harton GL, Munne S, Surrey M, et al; PGD Practitioners Group. Diminished effect of maternal age on implantation after preimplantation genetic diagnosis with array comparative genomic hybridization. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1695-1703.

- Mastenbroek S, Twisk M, van Echten-Arends, et al. In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:9-17

- Munne S, Kaplan B, Frattarelli JL, et al. Global multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing single embryo transfer with embryo selected by preimplantation genetic screening using next-generation sequencing versus morphologic assessment [abstract O-43]. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(suppl):e19.

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.

Professional societies, global organizations, and advocacy groups are continually working toward the goal of having the costs of infertility care covered by insurance carriers. Paramount to that effort is obtaining recognition of infertility as a burdensome disease. In this Update, we summarize national and international initiatives and societal trends that are helping to move us closer to that goal, and we encourage ObGyns to lead advocacy efforts.

Next, we detail several notable new features available in the annual report of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), an online interactive document that can be used to assist clinicians and patients in treatment decisions.

We also tackle the complexities of embryo selection for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and describe a potentially promising aneuploidy screening test, and explore its limitations.

Advances in recognizing infertility as a disease that merits insurance coverage

Major reproductive medicine organizations globally have endorsed the definition of infertility as a disease that "generates disability as an impairment of function" (TABLE 1).2 Fortunately, medical, societal, and judicial changes have resulted in progress for the 6.1 million women (and equivalent number of men) affected by infertility in the United States.3

Professional group advocacy efforts, and judicial rulings

The World Health Organization (WHO) has addressed infertility over the past several decades, with the organization's standards on semen analysis being the most recognized outcome. Progress has been limited, however, regarding global or national policy that recognizes the importance of infertility as a medical and public health problem.

In 2009, the glossary published by the WHO with the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) defined infertility as a disease.4 This recognition is important because it aids policy making, insurance coverage, and/or other payments for services.

The WHO also has begun the process of developing new infertility guidelines. Recently, the WHO held a summit on safety and access to fertility care, which was attended by many representatives of nation-state governments and international experts. It is hoped that a document from those proceedings will reinforce the public health importance of infertility and support the need to promote equality in access to safe fertility care. WHO initiatives matter because they apply to nation-states.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) for many years has recognized infertility as a disease. Only in 2017, however, did delegates at the American Medical Association's annual meeting vote to support the WHO's designation of infertility as a disease.

Continue to: Judicial views

Judicial views. In 1998, the US Supreme Court held that infertility is a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The Court subsequently held, however, that a person is not considered disabled under the act if the disability can be overcome by mitigating or corrective measures. In 2000, a lower court held that, while infertility is a disability, an employer's health plan that excludes treatment for it is not discriminatory under the ADA if it applies to all employees.

Societal recognition. Interestingly, improved technology for oocyte cryopreservation has resulted in greater recognition of reproductive issues and the disparity in reproductive health societal norms and rights between men and women.

Media stories and gender issues in employment, especially in such high-profile industries as technology and finance, have highlighted long-standing inequities, many of which concern reproductive issues. These issues have been further disseminated by the #metoo movement. Some employers are beginning to respond by recognizing their employees' reproductive needs and providing improved benefits for reproductive care.

ObGyns must continue to lead advocacy

Not all has been progress. Personhood bills in several states threaten basic reproductive rights of women and men. The ASRM and Resolve (the National Infertility Association) have taken leading roles in opposing these legislative initiatives and supporting reproductive rights.5

Advocacy efforts through events and trends have resulted in gradually improving the recognition of the burden of infertility, inadequate insurance coverage, and continuing gender inequalities in reproduction. Today, patients, professionals, and national and international organizations are coalescing around demands for recognition, access to care, and gender and diversity equality. While much remains to be done, progress is being made in society, government, the workplace, and the health care system.

ObGyns and other women's health care providers can help continue the progress toward equality in reproductive rights, including access to infertility care, by discussing insurance inequities with patients, informing insurance companies that infertility is a disease, and encouraging patients to challenge inadequate and unequal insurance coverage of needed reproductive health care.

The time is now for ObGyns and other women’s health care providers to advocate for insurance coverage of infertility care. When our patients have inadequate coverage, we should encourage them to take action by contacting their insurance company and their employers to explain the reasons and argue for better coverage. Also, contact RESOLVE for additional information.

Latest SART report offers new features to aid in treatment decision making

Knowledge of the prognosis and its various treatment options is an important aspect of infertility treatment. The SART recently updated its annual Clinic Summary Report (CSR), which includes valuable new features for patients and physicians considering assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment.6

SART compiles complex data and reports outcomes

The SART has been reporting IVF outcomes and other ART outcomes since 1988. The society's annual report is widely read by consumers, patients, physicians, and policy makers, and it has many important uses. However, the report is complicated and difficult to interpret for many reasons. For example, treatments are complex and varied (especially with application of new cryopreservation technology), and there are variations among clinics with respect to patient selection, protocols used, philosophy of practice, and numerous other variables.

Continue to: Because of this...

Because of this, the SART states, "The SART Clinic Summary Report (CSR) allows patients to view national and individual clinic IVF success rates. The data presented in this report should not be used for comparing clinics. Clinics may have differences in patient selection and treatment approaches which may artificially inflate or lower pregnancy rates relative to another clinic. Please discuss this with your doctor."6

Nevertheless, the CSR is extremely useful because it reports outcomes, which can lead to more informed patients and physicians and thus better access to safe and effective use of ART. The SART has redesigned the CSR to make it more useful.

Redesigned CSR focuses on outcomes important to patients

In recent years, new technologies have increased dramatically the use of embryo cryopreservation, genetic testing, and single embryo transfer (SET). The new CSR format is more patient focused and identifies more directly the treatment burden: ovarian stimulation, egg retrieval, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), cryopreservation, frozen embryo transfer, and multiple cycles. It also focuses on the important patient outcomes, including live birth of a healthy child, multiple pregnancy, number of cycles, and chances of success per patient over time (including both fresh and frozen embryo transfers).

Notable changes

A major change in the CSR is that there is a preliminary report for a given year and then a final report the following year. This helps to more accurately report cycles that have been "delayed" because of egg retrieval and embryo freezing performed in the reported year but then transferred in the following reporting year.

Cycle counting. A cycle is counted when a woman has started medications for an ART procedure or, in a "natural" cycle when no medications are used, the first day of menses of the ART cycle. If several cycles are performed to bank eggs or embryos, each will be counted in the denominator when calculating the pregnancy rate. This more accurately reflects the patient treatment burden and costs. A cycle cancelled before egg retrieval is still counted as a cycle.

Defining success. Success is characterized as delivery of a child, since this is the outcome patients desire. Singleton deliveries are emphasized, since twin and higher-order multiple pregnancies have a higher risk of prematurity, morbidity, mortality, and cost. The percentages of triplet, twin, and singleton births contributing to the live birth rate are provided for each cycle group, as is prematurity (TABLE 2).6

The end point of a treatment cycle can vary. The new CSR captures the success rate following one or more egg retrievals and the first embryo transfer (primary outcome), the success of subsequent cycles using frozen eggs or embryos not transferred in the first embryo transfer, and the combined contribution of the primary and subsequent cycles to the cumulative live birth rate for a patient both in the preliminary report and the final report for any given year. The live birth rate per patient also is reported and includes the outcomes for patients who are new to an infertility center and starting their first cycle for retrieval of their own eggs during the reporting year.

Continue to: Outcomes and prognostic factors...

Outcomes and prognostic factors. Outcomes are reported by multiple factors, including patient age and source of the eggs. These are important prognostic factors; separating the data allows you to obtain a better idea of both national and individual clinic experience by these factors.

The CSR also contains filters for infertility diagnosis, stimulation type, and other treatment details (FIGURE).6 The filter is a useful feature because multiple types of treatment can be included or excluded. The outcome of different treatment interventions can then be estimated based on outcomes from the entire sample of US patients with similar characteristics and interventions. This powerful tool can help patients and physicians choose the best treatment based on prognosis.

Personalized prognosis. An important new feature is the SART Patient Predictor (https://www.sartcorsonline.com/predictor/patient), a model that permits an individual patient to obtain a more personalized prognosis. While the SART predictor uses only basic patient information, such as age, body mass index, and diagnosis, its estimate is based on the entire US sample of reported ART experience and therefore can help patients in decision making. Furthermore, the predictor calculates percentages for the outcome of one transfer of 2 embryos, and 2 transfers of a single embryo, to demonstrate the advantages of SET that result in a higher live birth rate but a significantly lower multiple pregnancy rate.

Summing up

The SART's new CSR is extremely useful to patients and to any physician who cares for infertility patients. It can help users both understand the expected results from different ART treatments and enable better physician-patient communication and decision making.

The updated annual SART Clinic Summary Report is an exceptionally valuable and easy-to-use online tool for you and your infertility patients.

Embryo selection techniques refined with use of newer technologies

Since the introduction of IVF in 1978, the final cumulative live birth rates per cycle initiated for oocyte retrieval after all resulting embryos have been trasferred continue to rise, currently standing at 54% for women younger than age 35 in the United States.7 A number of achievements have contributed to this remarkable success, namely, improvements in IVF laboratory and embryo culture systems, advances in cryopreservation technology, availability of highly effective gonadotropins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, improved ultrasound technology, and the introduction of soft catheters for atraumatic embryo transfers.

Treatment now focuses on improved embryo selection

Now that excellent success rates have been attained, the focus of optimizing efforts in fertility treatment has shifted to improving safety by reducing the rates of multiple pregnancy through elective single embryo transfer (eSET), reducing the rates of miscarriage, and shortening the time to live birth. Methods to improve embryo selection lie at the forefront of these initiatives. These vary and include extended culture to blastocyst stage, standard morphologic evaluation as well as morphokinetic assessment of embryonic development via time-lapse imaging, and more recently the reintroduction of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), formerly known as preimplantation genetic screening (PGS).

Chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo, or embryo aneuploidies, are the most common cause of treatment failure following embryo transfer in IVF. The proportion of embryos affected with aneuploidies significantly increases with advancing maternal age: 40% to 50% of blastocysts in women younger than age 35 and about 90% of blastocysts in women older than age 42.8 The premise with PGT-A is to identify these aneuploid embryos and increase the chances of success per embryo transfer by transferring euploid embryos.

Continue to: That concept was initially applied...

That concept was initially applied to cleavage-stage embryos through the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology to interrogate a maximum of 5 to 9 chromosomes in a single cell (single blastomere); however, although initial results from observational studies were encouraging, subsequent randomized controlled studies unexpectedly showed a reduction in pregnancy rates.9 This was attributed to several factors, including biopsy-related damage to the cleavage-stage embryo, inability of FISH technology to assess aneuploidies of more than 5 to 9 chromosomes, mosaicism, and technical limitations associated with single-cell analysis.

Second-generation PGT-A testing has promise, and limitations

The newer PGT-A tests the embryos at the blastocyst stage by using biopsy samples from the trophectoderm (which will form the future placenta); this is expected to spare the inner cell mass ([ICM] which will give rise to the embryo proper) from biopsy-related injury.

On the genetics side, newer technologies, such as array comparative genomic hybridization, single nucleotide polymorphism arrays, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and next-generation sequencing, offer the opportunity to assess all 24 chromosomes in a single biopsy specimen. Although a detailed discussion of these testing platforms is beyond the scope of this Update, certain points are worth mentioning. All these technologies require some form of genetic material amplification (most commonly whole genome amplification or multiplex polymerase chain reaction) to increase the relatively scant amount of DNA obtained from a sample of 4 to 6 cells. These amplification techniques have limitations that can subsequently impact the validity of the test results.

Furthermore, there is no consistency in depth of coverage for various parts of the genome, and subchromosomal (segmental) copy number variations below 3 to 5 Mb may not be detected. The threshold used in bioinformatics algorithms employed to interpret the raw data is subject to several biases and is not consistent among laboratories. As a result, the same sample assessed in different laboratories can potentially yield different results.

In addition to these technical limitations, mosaicism can pose another biologic limitation, as the biopsied trophectoderm cells may not accurately represent the chromosomal makeup of the ICM. Also, an embryo may be able to undergo self-correction during subsequent stages of development, and therefore even a documented trophectoderm abnormality at the blastocyst stage may not necessarily preclude that embryo from developing into a healthy baby.

Standardization is needed. Despite widespread promotion of PGT-A, well-designed randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have not yet consistently shown its benefits in improving pregnancy rates or reducing miscarriage rates. Although the initial small RCTs in a selected group of good prognosis patients suggested a beneficial effect in ongoing pregnancy rates per transfer, the largest multicenter RCT to date did not show any improvement in pregnancy rates or reduction in miscarriage rates.10 In that study, a post hoc subgroup analysis suggested a possible beneficial effect in women aged 35 to 40. However, those results must be validated and reproduced with randomization at the start of stimulation, with the primary outcome being the live birth rate per initiated cycle, instead of per transfer, before PGT-A can be adopted universally in clinical practice.

Continue to: With all the above considerations...

With all the above considerations, the ASRM has appropriately concluded that "the value of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) as a screening test for IVF patients has yet to be determined."11

Standardization of clinical and laboratory protocols and additional studies to assess the effects of PGT-A on live birth rates per initiated cycles are recommended before this new technology is widely adopted in routine clinical practice. In our practice, we routinely offer and perform extended culture to blastocyst stage and standard morphologic assessment. After a thorough counseling on the current status of PGT-A, about 15% to 20% of our patients opt to undergo PGT-A.

Professional societies, global organizations, and advocacy groups are continually working toward the goal of having the costs of infertility care covered by insurance carriers. Paramount to that effort is obtaining recognition of infertility as a burdensome disease. In this Update, we summarize national and international initiatives and societal trends that are helping to move us closer to that goal, and we encourage ObGyns to lead advocacy efforts.

Next, we detail several notable new features available in the annual report of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), an online interactive document that can be used to assist clinicians and patients in treatment decisions.

We also tackle the complexities of embryo selection for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and describe a potentially promising aneuploidy screening test, and explore its limitations.

Advances in recognizing infertility as a disease that merits insurance coverage

Major reproductive medicine organizations globally have endorsed the definition of infertility as a disease that "generates disability as an impairment of function" (TABLE 1).2 Fortunately, medical, societal, and judicial changes have resulted in progress for the 6.1 million women (and equivalent number of men) affected by infertility in the United States.3

Professional group advocacy efforts, and judicial rulings

The World Health Organization (WHO) has addressed infertility over the past several decades, with the organization's standards on semen analysis being the most recognized outcome. Progress has been limited, however, regarding global or national policy that recognizes the importance of infertility as a medical and public health problem.

In 2009, the glossary published by the WHO with the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) defined infertility as a disease.4 This recognition is important because it aids policy making, insurance coverage, and/or other payments for services.

The WHO also has begun the process of developing new infertility guidelines. Recently, the WHO held a summit on safety and access to fertility care, which was attended by many representatives of nation-state governments and international experts. It is hoped that a document from those proceedings will reinforce the public health importance of infertility and support the need to promote equality in access to safe fertility care. WHO initiatives matter because they apply to nation-states.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) for many years has recognized infertility as a disease. Only in 2017, however, did delegates at the American Medical Association's annual meeting vote to support the WHO's designation of infertility as a disease.

Continue to: Judicial views

Judicial views. In 1998, the US Supreme Court held that infertility is a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The Court subsequently held, however, that a person is not considered disabled under the act if the disability can be overcome by mitigating or corrective measures. In 2000, a lower court held that, while infertility is a disability, an employer's health plan that excludes treatment for it is not discriminatory under the ADA if it applies to all employees.

Societal recognition. Interestingly, improved technology for oocyte cryopreservation has resulted in greater recognition of reproductive issues and the disparity in reproductive health societal norms and rights between men and women.

Media stories and gender issues in employment, especially in such high-profile industries as technology and finance, have highlighted long-standing inequities, many of which concern reproductive issues. These issues have been further disseminated by the #metoo movement. Some employers are beginning to respond by recognizing their employees' reproductive needs and providing improved benefits for reproductive care.

ObGyns must continue to lead advocacy

Not all has been progress. Personhood bills in several states threaten basic reproductive rights of women and men. The ASRM and Resolve (the National Infertility Association) have taken leading roles in opposing these legislative initiatives and supporting reproductive rights.5

Advocacy efforts through events and trends have resulted in gradually improving the recognition of the burden of infertility, inadequate insurance coverage, and continuing gender inequalities in reproduction. Today, patients, professionals, and national and international organizations are coalescing around demands for recognition, access to care, and gender and diversity equality. While much remains to be done, progress is being made in society, government, the workplace, and the health care system.

ObGyns and other women's health care providers can help continue the progress toward equality in reproductive rights, including access to infertility care, by discussing insurance inequities with patients, informing insurance companies that infertility is a disease, and encouraging patients to challenge inadequate and unequal insurance coverage of needed reproductive health care.

The time is now for ObGyns and other women’s health care providers to advocate for insurance coverage of infertility care. When our patients have inadequate coverage, we should encourage them to take action by contacting their insurance company and their employers to explain the reasons and argue for better coverage. Also, contact RESOLVE for additional information.

Latest SART report offers new features to aid in treatment decision making

Knowledge of the prognosis and its various treatment options is an important aspect of infertility treatment. The SART recently updated its annual Clinic Summary Report (CSR), which includes valuable new features for patients and physicians considering assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment.6

SART compiles complex data and reports outcomes

The SART has been reporting IVF outcomes and other ART outcomes since 1988. The society's annual report is widely read by consumers, patients, physicians, and policy makers, and it has many important uses. However, the report is complicated and difficult to interpret for many reasons. For example, treatments are complex and varied (especially with application of new cryopreservation technology), and there are variations among clinics with respect to patient selection, protocols used, philosophy of practice, and numerous other variables.

Continue to: Because of this...

Because of this, the SART states, "The SART Clinic Summary Report (CSR) allows patients to view national and individual clinic IVF success rates. The data presented in this report should not be used for comparing clinics. Clinics may have differences in patient selection and treatment approaches which may artificially inflate or lower pregnancy rates relative to another clinic. Please discuss this with your doctor."6

Nevertheless, the CSR is extremely useful because it reports outcomes, which can lead to more informed patients and physicians and thus better access to safe and effective use of ART. The SART has redesigned the CSR to make it more useful.

Redesigned CSR focuses on outcomes important to patients

In recent years, new technologies have increased dramatically the use of embryo cryopreservation, genetic testing, and single embryo transfer (SET). The new CSR format is more patient focused and identifies more directly the treatment burden: ovarian stimulation, egg retrieval, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), cryopreservation, frozen embryo transfer, and multiple cycles. It also focuses on the important patient outcomes, including live birth of a healthy child, multiple pregnancy, number of cycles, and chances of success per patient over time (including both fresh and frozen embryo transfers).

Notable changes

A major change in the CSR is that there is a preliminary report for a given year and then a final report the following year. This helps to more accurately report cycles that have been "delayed" because of egg retrieval and embryo freezing performed in the reported year but then transferred in the following reporting year.

Cycle counting. A cycle is counted when a woman has started medications for an ART procedure or, in a "natural" cycle when no medications are used, the first day of menses of the ART cycle. If several cycles are performed to bank eggs or embryos, each will be counted in the denominator when calculating the pregnancy rate. This more accurately reflects the patient treatment burden and costs. A cycle cancelled before egg retrieval is still counted as a cycle.

Defining success. Success is characterized as delivery of a child, since this is the outcome patients desire. Singleton deliveries are emphasized, since twin and higher-order multiple pregnancies have a higher risk of prematurity, morbidity, mortality, and cost. The percentages of triplet, twin, and singleton births contributing to the live birth rate are provided for each cycle group, as is prematurity (TABLE 2).6

The end point of a treatment cycle can vary. The new CSR captures the success rate following one or more egg retrievals and the first embryo transfer (primary outcome), the success of subsequent cycles using frozen eggs or embryos not transferred in the first embryo transfer, and the combined contribution of the primary and subsequent cycles to the cumulative live birth rate for a patient both in the preliminary report and the final report for any given year. The live birth rate per patient also is reported and includes the outcomes for patients who are new to an infertility center and starting their first cycle for retrieval of their own eggs during the reporting year.

Continue to: Outcomes and prognostic factors...

Outcomes and prognostic factors. Outcomes are reported by multiple factors, including patient age and source of the eggs. These are important prognostic factors; separating the data allows you to obtain a better idea of both national and individual clinic experience by these factors.

The CSR also contains filters for infertility diagnosis, stimulation type, and other treatment details (FIGURE).6 The filter is a useful feature because multiple types of treatment can be included or excluded. The outcome of different treatment interventions can then be estimated based on outcomes from the entire sample of US patients with similar characteristics and interventions. This powerful tool can help patients and physicians choose the best treatment based on prognosis.

Personalized prognosis. An important new feature is the SART Patient Predictor (https://www.sartcorsonline.com/predictor/patient), a model that permits an individual patient to obtain a more personalized prognosis. While the SART predictor uses only basic patient information, such as age, body mass index, and diagnosis, its estimate is based on the entire US sample of reported ART experience and therefore can help patients in decision making. Furthermore, the predictor calculates percentages for the outcome of one transfer of 2 embryos, and 2 transfers of a single embryo, to demonstrate the advantages of SET that result in a higher live birth rate but a significantly lower multiple pregnancy rate.

Summing up

The SART's new CSR is extremely useful to patients and to any physician who cares for infertility patients. It can help users both understand the expected results from different ART treatments and enable better physician-patient communication and decision making.

The updated annual SART Clinic Summary Report is an exceptionally valuable and easy-to-use online tool for you and your infertility patients.

Embryo selection techniques refined with use of newer technologies

Since the introduction of IVF in 1978, the final cumulative live birth rates per cycle initiated for oocyte retrieval after all resulting embryos have been trasferred continue to rise, currently standing at 54% for women younger than age 35 in the United States.7 A number of achievements have contributed to this remarkable success, namely, improvements in IVF laboratory and embryo culture systems, advances in cryopreservation technology, availability of highly effective gonadotropins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, improved ultrasound technology, and the introduction of soft catheters for atraumatic embryo transfers.

Treatment now focuses on improved embryo selection

Now that excellent success rates have been attained, the focus of optimizing efforts in fertility treatment has shifted to improving safety by reducing the rates of multiple pregnancy through elective single embryo transfer (eSET), reducing the rates of miscarriage, and shortening the time to live birth. Methods to improve embryo selection lie at the forefront of these initiatives. These vary and include extended culture to blastocyst stage, standard morphologic evaluation as well as morphokinetic assessment of embryonic development via time-lapse imaging, and more recently the reintroduction of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), formerly known as preimplantation genetic screening (PGS).

Chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo, or embryo aneuploidies, are the most common cause of treatment failure following embryo transfer in IVF. The proportion of embryos affected with aneuploidies significantly increases with advancing maternal age: 40% to 50% of blastocysts in women younger than age 35 and about 90% of blastocysts in women older than age 42.8 The premise with PGT-A is to identify these aneuploid embryos and increase the chances of success per embryo transfer by transferring euploid embryos.

Continue to: That concept was initially applied...

That concept was initially applied to cleavage-stage embryos through the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology to interrogate a maximum of 5 to 9 chromosomes in a single cell (single blastomere); however, although initial results from observational studies were encouraging, subsequent randomized controlled studies unexpectedly showed a reduction in pregnancy rates.9 This was attributed to several factors, including biopsy-related damage to the cleavage-stage embryo, inability of FISH technology to assess aneuploidies of more than 5 to 9 chromosomes, mosaicism, and technical limitations associated with single-cell analysis.

Second-generation PGT-A testing has promise, and limitations

The newer PGT-A tests the embryos at the blastocyst stage by using biopsy samples from the trophectoderm (which will form the future placenta); this is expected to spare the inner cell mass ([ICM] which will give rise to the embryo proper) from biopsy-related injury.

On the genetics side, newer technologies, such as array comparative genomic hybridization, single nucleotide polymorphism arrays, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and next-generation sequencing, offer the opportunity to assess all 24 chromosomes in a single biopsy specimen. Although a detailed discussion of these testing platforms is beyond the scope of this Update, certain points are worth mentioning. All these technologies require some form of genetic material amplification (most commonly whole genome amplification or multiplex polymerase chain reaction) to increase the relatively scant amount of DNA obtained from a sample of 4 to 6 cells. These amplification techniques have limitations that can subsequently impact the validity of the test results.

Furthermore, there is no consistency in depth of coverage for various parts of the genome, and subchromosomal (segmental) copy number variations below 3 to 5 Mb may not be detected. The threshold used in bioinformatics algorithms employed to interpret the raw data is subject to several biases and is not consistent among laboratories. As a result, the same sample assessed in different laboratories can potentially yield different results.

In addition to these technical limitations, mosaicism can pose another biologic limitation, as the biopsied trophectoderm cells may not accurately represent the chromosomal makeup of the ICM. Also, an embryo may be able to undergo self-correction during subsequent stages of development, and therefore even a documented trophectoderm abnormality at the blastocyst stage may not necessarily preclude that embryo from developing into a healthy baby.

Standardization is needed. Despite widespread promotion of PGT-A, well-designed randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have not yet consistently shown its benefits in improving pregnancy rates or reducing miscarriage rates. Although the initial small RCTs in a selected group of good prognosis patients suggested a beneficial effect in ongoing pregnancy rates per transfer, the largest multicenter RCT to date did not show any improvement in pregnancy rates or reduction in miscarriage rates.10 In that study, a post hoc subgroup analysis suggested a possible beneficial effect in women aged 35 to 40. However, those results must be validated and reproduced with randomization at the start of stimulation, with the primary outcome being the live birth rate per initiated cycle, instead of per transfer, before PGT-A can be adopted universally in clinical practice.

Continue to: With all the above considerations...

With all the above considerations, the ASRM has appropriately concluded that "the value of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) as a screening test for IVF patients has yet to be determined."11

Standardization of clinical and laboratory protocols and additional studies to assess the effects of PGT-A on live birth rates per initiated cycles are recommended before this new technology is widely adopted in routine clinical practice. In our practice, we routinely offer and perform extended culture to blastocyst stage and standard morphologic assessment. After a thorough counseling on the current status of PGT-A, about 15% to 20% of our patients opt to undergo PGT-A.

- United Nations website. General Assembly resolution 217A: Declaration of human rights. December 10, 1948. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declara tion-human-rights/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:393-406.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women's Health website. Infertility. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/infertility. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology, World Health Organization. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1520-1524.

- RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association website. Opposing personhood: Resolve fights to keep fertility medical treatments legal in the US. https://resolve.org/get-involved/advocate-for-access/our-issues/opposing-personhood/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report. 2016 Preliminary national data. https://www.sartcorsonline.com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx?reportingYear=2016 . Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report 2015. https://www.sartcorsonline,com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx ?reportingYear=2015. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Harton GL, Munne S, Surrey M, et al; PGD Practitioners Group. Diminished effect of maternal age on implantation after preimplantation genetic diagnosis with array comparative genomic hybridization. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1695-1703.

- Mastenbroek S, Twisk M, van Echten-Arends, et al. In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:9-17

- Munne S, Kaplan B, Frattarelli JL, et al. Global multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing single embryo transfer with embryo selected by preimplantation genetic screening using next-generation sequencing versus morphologic assessment [abstract O-43]. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(suppl):e19.

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.

- United Nations website. General Assembly resolution 217A: Declaration of human rights. December 10, 1948. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declara tion-human-rights/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:393-406.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women's Health website. Infertility. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/infertility. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology, World Health Organization. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1520-1524.

- RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association website. Opposing personhood: Resolve fights to keep fertility medical treatments legal in the US. https://resolve.org/get-involved/advocate-for-access/our-issues/opposing-personhood/. Accessed January 11, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report. 2016 Preliminary national data. https://www.sartcorsonline.com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx?reportingYear=2016 . Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology website. National summary report 2015. https://www.sartcorsonline,com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx ?reportingYear=2015. Accessed January 12, 2019.

- Harton GL, Munne S, Surrey M, et al; PGD Practitioners Group. Diminished effect of maternal age on implantation after preimplantation genetic diagnosis with array comparative genomic hybridization. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1695-1703.

- Mastenbroek S, Twisk M, van Echten-Arends, et al. In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:9-17

- Munne S, Kaplan B, Frattarelli JL, et al. Global multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing single embryo transfer with embryo selected by preimplantation genetic screening using next-generation sequencing versus morphologic assessment [abstract O-43]. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(suppl):e19.

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.