User login

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

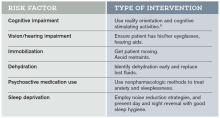

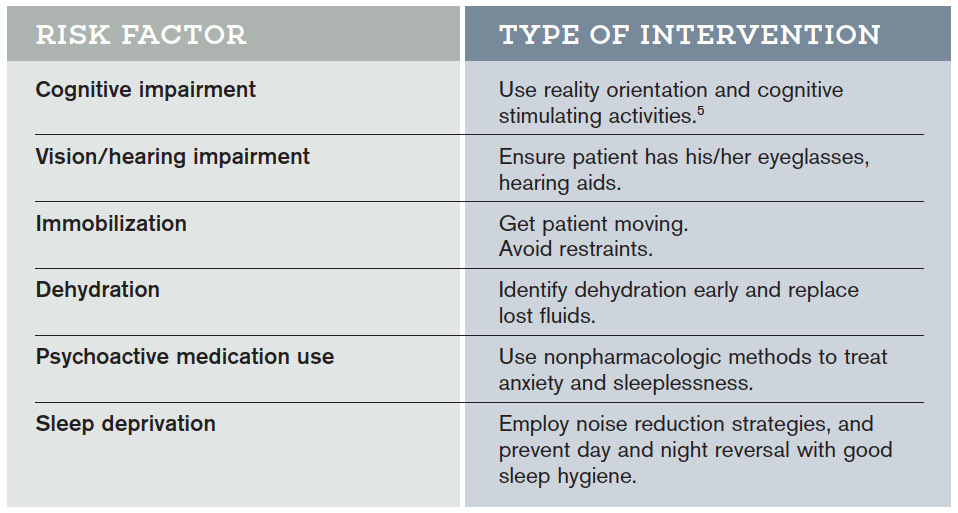

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.