User login

Confusion recurs 2 weeks after fall

A 77-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a headache following a syncopal episode (while standing) earlier that day. She said that she’d lost consciousness for several minutes, and then experienced several minutes of mild confusion that resolved spontaneously.

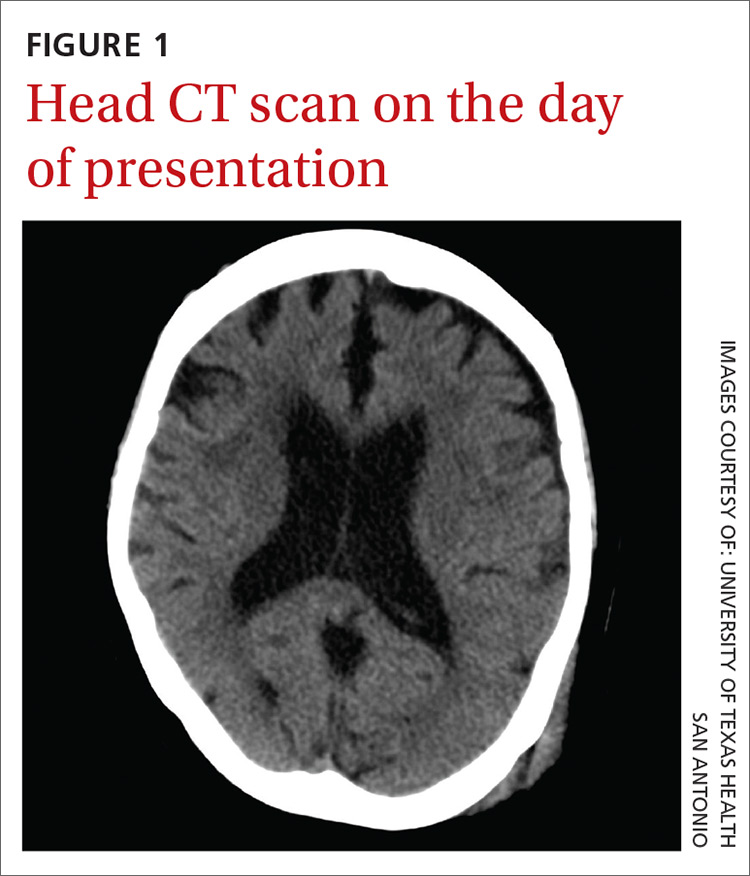

On physical exam, she was oriented to person and place, but not time. She had a contusion in her left occipitoparietal region without extensive bruising or deformity. The patient had normal cardiopulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic exams. Her past medical history included hypertension and normal pressure hydrocephalus, and her vital signs were within normal limits. She was taking aspirin once daily.The patient’s initial head and neck computerized tomography (CT) scans were normal (FIGURE 1), but she was hospitalized because of her confusion. During her hospitalization, the patient had mild episodic headaches that resolved with acetaminophen. The next day, her confusion resolved, and repeat CT scans were unchanged. She was discharged within 24 hours.

Two weeks later, the patient returned to the hospital after her daughter found her on the toilet, unable to stand up from the sitting position. She was confused and experienced a worsening of headache during transport to the hospital. No recurrent falls or additional episodes of trauma were reported. A CT scan was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Delayed acute subdural hematoma

The CT scan (FIGURE 2) revealed an acute on chronic large left frontotemporoparietal and a right frontoparietal subdural hematoma (SDH) with resultant left to right subfalcine herniation. The patient was given a diagnosis of a delayed acute subdural hematoma (DASH)—an acute subdural hematoma that is not apparent on an initial CT scan, but is detected on follow-up CT imaging days or weeks after the injury.1 The incidence of DASH is approximately 0.5% among acute SDH patients who require operative treatment.1

Because DASH is rare, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding its presentation, pathophysiology, and outcomes. In the few cases that have been described, patients have varied from those who were healthy, and had no coagulation abnormalities, to those who were elderly and taking anticoagulants.2,3 In addition, the period between the head injury and the development of SDH is variable.3

While not much is known about DASH, the mechanism of acute SDH has been widely studied and researched. Acute SDH, which typically follows a head trauma, results from the tearing of bridging veins that lack supporting structures and are most vulnerable to injury when crossing the subdural space.4 The potential pathophysiology for DASH is not completely understood, but is likely to involve subtle damage to the bridging veins of the brain that continue to leak over a matter of hours and days.1,5

Two risk factors to consider. Increasing age and use of oral anticoagulants can increase the risk of developing an intracranial lesion after head injury.3 Due to the infrequency of DASH, the same risk factors for SDH should be considered for DASH. These factors make it increasingly important to establish guidelines on how to approach mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) in both DASH and SDH, especially for those who are elderly or have been on anticoagulation therapy.

Differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s decline and altered mentation weeks after the initial event included worsening normal pressure hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular accident, and seizure.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus typically has a more chronic onset than DASH. It manifests with the classic triad of dementia, incontinence, and magnetic or festinating gait (“wild, wet, and wobbly”).

Cerebrovascular accidents are most often associated with focal neurologic deficits, which can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. If hemorrhagic, the hemorrhage is typically parenchymal and not subdural.

Seizure, especially partial complex seizure, can arise after trauma and may not involve obvious motor movements. Symptoms generally abate over a few minutes to hours with treatment. Electroencephalogram and CT scan can differentiate seizure from a subdural hematoma.

Keep DASH on your radar screen

The American College of Emergency Physicians states that a non-contrast head CT scan is indicated in head trauma patients with loss of consciousness if one or more of the following is present: age >60 years, vomiting, headache, drug or alcohol intoxication, short-term memory deficits, posttraumatic seizure, Glasgow Coma Scale score of <15, focal neurologic deficits, and coagulopathy.6

Some have suggested that the initial head CT scan be delayed by up to 8 hours to prevent missing a slowly developing intracranial hemorrhage. Others suggest that the CT scan be repeated at 24 hours. Still others have suggested that patients with even mild TBI be admitted for a period of observation if any risk factors, such as age or history of anticoagulation therapy, are noted.

Because there is no evidence to support delaying the initial head CT scan, physicians should be thorough in their evaluation of head trauma patients with loss of consciousness and consider a repeat CT scan of the head if worsening of any symptoms occurs. Physicians should also consider a repeat CT scan of the head for patients at high risk, including the elderly and those who have taken anticoagulants.

In addition, patients with traumatic head injuries must be properly counseled to return if they experience repeated vomiting, worsening headache, memory loss, confusion, focal neurologic deficit, abnormal behavior, increased sleepiness, or seizures.6 An extra precaution for high-risk patients includes suggesting adequate follow-up with a primary care physician to help monitor recovery and prevent any occurrences of DASH from going unnoticed.

Our patient underwent a mini-craniotomy. Postoperatively, she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility and ultimately made a complete recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrew Muck, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, MSC 7736, San Antonio, TX 78229; muck@uthscsa.edu.

1. Cohen T, Gudeman S. In: Narayan RK, ed. Delayed Traumatic Intracranial Hematoma. Neurotrauma. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;1995:689-701.

2. Matsuda W, Sugimoto K, Sato N, et al. Delayed onset of posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma after mild head injury with normal computed tomography: a case report and brief review. J Trauma. 2008;65:461-463.

3. Itshayek E, Rosenthal G, Fraifeld S, et al. Delayed posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma in elderly patients on anticoagulation. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:E851-E856.

4. Culotta VP, Sermentilli ME, Gerold K, et al. Clinicopathological heterogeneity in the classification of mild head injury. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:245-250.

5. Shabani S, Nguyen HS, Doan N, et al. Case Report and Review of Literature of Delayed Acute Subdural Hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:66-71.

6. Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns Jr JJ, et al. Clinical Policy: Neuroimaging and Decisionmaking in Adult Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the Acute Setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:714-748.

A 77-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a headache following a syncopal episode (while standing) earlier that day. She said that she’d lost consciousness for several minutes, and then experienced several minutes of mild confusion that resolved spontaneously.

On physical exam, she was oriented to person and place, but not time. She had a contusion in her left occipitoparietal region without extensive bruising or deformity. The patient had normal cardiopulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic exams. Her past medical history included hypertension and normal pressure hydrocephalus, and her vital signs were within normal limits. She was taking aspirin once daily.The patient’s initial head and neck computerized tomography (CT) scans were normal (FIGURE 1), but she was hospitalized because of her confusion. During her hospitalization, the patient had mild episodic headaches that resolved with acetaminophen. The next day, her confusion resolved, and repeat CT scans were unchanged. She was discharged within 24 hours.

Two weeks later, the patient returned to the hospital after her daughter found her on the toilet, unable to stand up from the sitting position. She was confused and experienced a worsening of headache during transport to the hospital. No recurrent falls or additional episodes of trauma were reported. A CT scan was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Delayed acute subdural hematoma

The CT scan (FIGURE 2) revealed an acute on chronic large left frontotemporoparietal and a right frontoparietal subdural hematoma (SDH) with resultant left to right subfalcine herniation. The patient was given a diagnosis of a delayed acute subdural hematoma (DASH)—an acute subdural hematoma that is not apparent on an initial CT scan, but is detected on follow-up CT imaging days or weeks after the injury.1 The incidence of DASH is approximately 0.5% among acute SDH patients who require operative treatment.1

Because DASH is rare, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding its presentation, pathophysiology, and outcomes. In the few cases that have been described, patients have varied from those who were healthy, and had no coagulation abnormalities, to those who were elderly and taking anticoagulants.2,3 In addition, the period between the head injury and the development of SDH is variable.3

While not much is known about DASH, the mechanism of acute SDH has been widely studied and researched. Acute SDH, which typically follows a head trauma, results from the tearing of bridging veins that lack supporting structures and are most vulnerable to injury when crossing the subdural space.4 The potential pathophysiology for DASH is not completely understood, but is likely to involve subtle damage to the bridging veins of the brain that continue to leak over a matter of hours and days.1,5

Two risk factors to consider. Increasing age and use of oral anticoagulants can increase the risk of developing an intracranial lesion after head injury.3 Due to the infrequency of DASH, the same risk factors for SDH should be considered for DASH. These factors make it increasingly important to establish guidelines on how to approach mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) in both DASH and SDH, especially for those who are elderly or have been on anticoagulation therapy.

Differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s decline and altered mentation weeks after the initial event included worsening normal pressure hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular accident, and seizure.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus typically has a more chronic onset than DASH. It manifests with the classic triad of dementia, incontinence, and magnetic or festinating gait (“wild, wet, and wobbly”).

Cerebrovascular accidents are most often associated with focal neurologic deficits, which can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. If hemorrhagic, the hemorrhage is typically parenchymal and not subdural.

Seizure, especially partial complex seizure, can arise after trauma and may not involve obvious motor movements. Symptoms generally abate over a few minutes to hours with treatment. Electroencephalogram and CT scan can differentiate seizure from a subdural hematoma.

Keep DASH on your radar screen

The American College of Emergency Physicians states that a non-contrast head CT scan is indicated in head trauma patients with loss of consciousness if one or more of the following is present: age >60 years, vomiting, headache, drug or alcohol intoxication, short-term memory deficits, posttraumatic seizure, Glasgow Coma Scale score of <15, focal neurologic deficits, and coagulopathy.6

Some have suggested that the initial head CT scan be delayed by up to 8 hours to prevent missing a slowly developing intracranial hemorrhage. Others suggest that the CT scan be repeated at 24 hours. Still others have suggested that patients with even mild TBI be admitted for a period of observation if any risk factors, such as age or history of anticoagulation therapy, are noted.

Because there is no evidence to support delaying the initial head CT scan, physicians should be thorough in their evaluation of head trauma patients with loss of consciousness and consider a repeat CT scan of the head if worsening of any symptoms occurs. Physicians should also consider a repeat CT scan of the head for patients at high risk, including the elderly and those who have taken anticoagulants.

In addition, patients with traumatic head injuries must be properly counseled to return if they experience repeated vomiting, worsening headache, memory loss, confusion, focal neurologic deficit, abnormal behavior, increased sleepiness, or seizures.6 An extra precaution for high-risk patients includes suggesting adequate follow-up with a primary care physician to help monitor recovery and prevent any occurrences of DASH from going unnoticed.

Our patient underwent a mini-craniotomy. Postoperatively, she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility and ultimately made a complete recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrew Muck, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, MSC 7736, San Antonio, TX 78229; muck@uthscsa.edu.

A 77-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a headache following a syncopal episode (while standing) earlier that day. She said that she’d lost consciousness for several minutes, and then experienced several minutes of mild confusion that resolved spontaneously.

On physical exam, she was oriented to person and place, but not time. She had a contusion in her left occipitoparietal region without extensive bruising or deformity. The patient had normal cardiopulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic exams. Her past medical history included hypertension and normal pressure hydrocephalus, and her vital signs were within normal limits. She was taking aspirin once daily.The patient’s initial head and neck computerized tomography (CT) scans were normal (FIGURE 1), but she was hospitalized because of her confusion. During her hospitalization, the patient had mild episodic headaches that resolved with acetaminophen. The next day, her confusion resolved, and repeat CT scans were unchanged. She was discharged within 24 hours.

Two weeks later, the patient returned to the hospital after her daughter found her on the toilet, unable to stand up from the sitting position. She was confused and experienced a worsening of headache during transport to the hospital. No recurrent falls or additional episodes of trauma were reported. A CT scan was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Delayed acute subdural hematoma

The CT scan (FIGURE 2) revealed an acute on chronic large left frontotemporoparietal and a right frontoparietal subdural hematoma (SDH) with resultant left to right subfalcine herniation. The patient was given a diagnosis of a delayed acute subdural hematoma (DASH)—an acute subdural hematoma that is not apparent on an initial CT scan, but is detected on follow-up CT imaging days or weeks after the injury.1 The incidence of DASH is approximately 0.5% among acute SDH patients who require operative treatment.1

Because DASH is rare, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding its presentation, pathophysiology, and outcomes. In the few cases that have been described, patients have varied from those who were healthy, and had no coagulation abnormalities, to those who were elderly and taking anticoagulants.2,3 In addition, the period between the head injury and the development of SDH is variable.3

While not much is known about DASH, the mechanism of acute SDH has been widely studied and researched. Acute SDH, which typically follows a head trauma, results from the tearing of bridging veins that lack supporting structures and are most vulnerable to injury when crossing the subdural space.4 The potential pathophysiology for DASH is not completely understood, but is likely to involve subtle damage to the bridging veins of the brain that continue to leak over a matter of hours and days.1,5

Two risk factors to consider. Increasing age and use of oral anticoagulants can increase the risk of developing an intracranial lesion after head injury.3 Due to the infrequency of DASH, the same risk factors for SDH should be considered for DASH. These factors make it increasingly important to establish guidelines on how to approach mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) in both DASH and SDH, especially for those who are elderly or have been on anticoagulation therapy.

Differential Dx

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s decline and altered mentation weeks after the initial event included worsening normal pressure hydrocephalus, cerebrovascular accident, and seizure.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus typically has a more chronic onset than DASH. It manifests with the classic triad of dementia, incontinence, and magnetic or festinating gait (“wild, wet, and wobbly”).

Cerebrovascular accidents are most often associated with focal neurologic deficits, which can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. If hemorrhagic, the hemorrhage is typically parenchymal and not subdural.

Seizure, especially partial complex seizure, can arise after trauma and may not involve obvious motor movements. Symptoms generally abate over a few minutes to hours with treatment. Electroencephalogram and CT scan can differentiate seizure from a subdural hematoma.

Keep DASH on your radar screen

The American College of Emergency Physicians states that a non-contrast head CT scan is indicated in head trauma patients with loss of consciousness if one or more of the following is present: age >60 years, vomiting, headache, drug or alcohol intoxication, short-term memory deficits, posttraumatic seizure, Glasgow Coma Scale score of <15, focal neurologic deficits, and coagulopathy.6

Some have suggested that the initial head CT scan be delayed by up to 8 hours to prevent missing a slowly developing intracranial hemorrhage. Others suggest that the CT scan be repeated at 24 hours. Still others have suggested that patients with even mild TBI be admitted for a period of observation if any risk factors, such as age or history of anticoagulation therapy, are noted.

Because there is no evidence to support delaying the initial head CT scan, physicians should be thorough in their evaluation of head trauma patients with loss of consciousness and consider a repeat CT scan of the head if worsening of any symptoms occurs. Physicians should also consider a repeat CT scan of the head for patients at high risk, including the elderly and those who have taken anticoagulants.

In addition, patients with traumatic head injuries must be properly counseled to return if they experience repeated vomiting, worsening headache, memory loss, confusion, focal neurologic deficit, abnormal behavior, increased sleepiness, or seizures.6 An extra precaution for high-risk patients includes suggesting adequate follow-up with a primary care physician to help monitor recovery and prevent any occurrences of DASH from going unnoticed.

Our patient underwent a mini-craniotomy. Postoperatively, she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility and ultimately made a complete recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrew Muck, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, MSC 7736, San Antonio, TX 78229; muck@uthscsa.edu.

1. Cohen T, Gudeman S. In: Narayan RK, ed. Delayed Traumatic Intracranial Hematoma. Neurotrauma. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;1995:689-701.

2. Matsuda W, Sugimoto K, Sato N, et al. Delayed onset of posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma after mild head injury with normal computed tomography: a case report and brief review. J Trauma. 2008;65:461-463.

3. Itshayek E, Rosenthal G, Fraifeld S, et al. Delayed posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma in elderly patients on anticoagulation. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:E851-E856.

4. Culotta VP, Sermentilli ME, Gerold K, et al. Clinicopathological heterogeneity in the classification of mild head injury. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:245-250.

5. Shabani S, Nguyen HS, Doan N, et al. Case Report and Review of Literature of Delayed Acute Subdural Hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:66-71.

6. Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns Jr JJ, et al. Clinical Policy: Neuroimaging and Decisionmaking in Adult Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the Acute Setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:714-748.

1. Cohen T, Gudeman S. In: Narayan RK, ed. Delayed Traumatic Intracranial Hematoma. Neurotrauma. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;1995:689-701.

2. Matsuda W, Sugimoto K, Sato N, et al. Delayed onset of posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma after mild head injury with normal computed tomography: a case report and brief review. J Trauma. 2008;65:461-463.

3. Itshayek E, Rosenthal G, Fraifeld S, et al. Delayed posttraumatic acute subdural hematoma in elderly patients on anticoagulation. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:E851-E856.

4. Culotta VP, Sermentilli ME, Gerold K, et al. Clinicopathological heterogeneity in the classification of mild head injury. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:245-250.

5. Shabani S, Nguyen HS, Doan N, et al. Case Report and Review of Literature of Delayed Acute Subdural Hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:66-71.

6. Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns Jr JJ, et al. Clinical Policy: Neuroimaging and Decisionmaking in Adult Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the Acute Setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:714-748.